This article is part of the Brookings Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative’s “Digital Prosperity” blog series, which examines how regions across the country are using innovative strategies to respond to a range of digital inclusion challenges.

As COVID-19 requires more and more swaths of the country to shelter at home, broadband is more essential than ever. Access to the internet means having the ability to work from home, connecting with friends and family, and ordering food and other essential goods online. For businesses, it allows the possibility of staying open without relying on foot traffic and carrying out essential functions remotely.

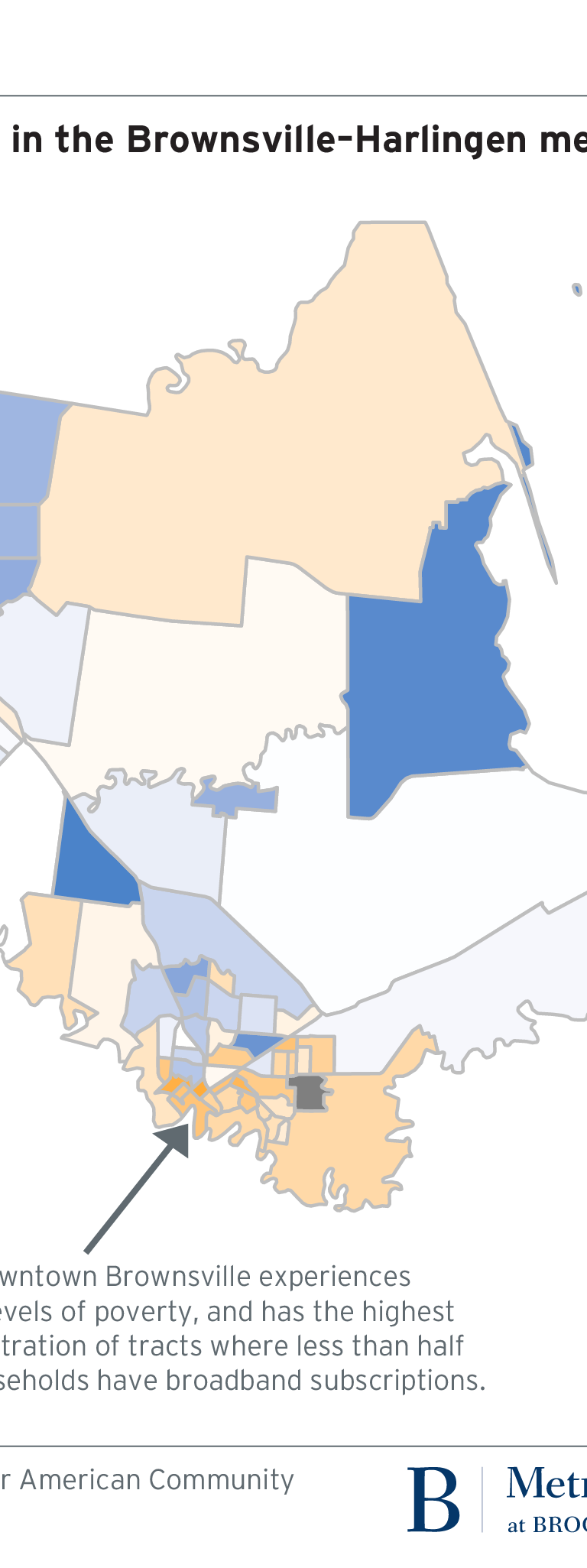

Adjusting to life in a digital space is straightforward for some of us. But for households and businesses without a broadband subscription, life under quarantine is an entirely different picture. As part of a larger project around digital equity, we visited Texas’s Brownsville-Harlingen metropolitan area, a community with low rates of broadband adoption and spotty service. In Brownsville, it’s a challenge for students to keep up with school assignments, for the police department to upload reports, and for residents to maintain connections. They are not alone in these challenges, but we can look to this community to better understand the opportunities for overcoming barriers to broadband adoption.

Brownsville sits on the U.S.-Mexico border and is home to 423,908 residents, the majority of whom (89.8%) identify as Latino or Hispanic. The region has an overall poverty rate of 28%, and for those under 18, the poverty rate is 41.1%. The area also has a significantly lower broadband adoption rate than the rest of the country: Only half of all households have any type of broadband connection (compared with 85.1% nationally), and 11% of households only have a cellular connection.

Leaders in the region—including the city manager, the head of the Brownsville Community Improvement Corporation, and representatives from local health and housing centers—all know that to improve economic conditions, they need to increase broadband penetration, adoption, and use. To get there, they are capitalizing on the region’s already-strong network of trusted community members as well as the entrepreneurial spirit deeply interwoven within the region’s workforce.

The goals for a more connected Brownsville may be clear, but the interventions aren’t easy. The region has long struggled to attract internet service providers (ISPs) to connect every neighborhood, and there isn’t enough disposable household income for every resident to afford a broadband subscription. The lack of digital connectivity creates economic headwinds; stakeholders noted that some companies have left the region due to the lack of broadband access and adoption, which constrains their business growth.

Likewise, the ability to spark entrepreneurial growth is limited if small business owners, their clients, and the future workforce are not digitally connected. Stakeholders noted that keeping promising young entrepreneurs in Brownsville is a challenge. And since many students are unable to connect to digital education services at home—including in publicly supported housing—they are unable to build the skills necessary for a digitalizing workforce.

Broadband inequities spill out from the business community to the health care sector, too. A lack of access and adoption prevents providers from addressing mounting concerns around health and access to quality health care. Compared to the national average, the border region faces a higher prevalence of diabetes and related conditions. Though the causes of these outcomes are complex, providers know over half of all cases in certain counties in the border region go untreated.

For example, the Area Health Education Center (AHEC) at Brownsville’s Bob Clark Social Service Center has found that the most common reason people do not use the facility’s free health services is a lack of transportation or awareness around appointments. Expanded broadband access would allow patients to manage appointments online and make preliminary contact with doctors from home. AHEC is already taking advantage of the broadband available in the clinic by connecting patients to specialists via equipment that transmits images and vitals to remote locations.

Thankfully, the health care sector in this region offers a unique solution to tackle digital skills challenges: promotoras, who are community health workers from local Latino or Hispanic communities. Promotoras are supported by county health departments, and due to the nature of their work, they are already integrated and trusted in their communities. They can leverage their trust and relationships to educate residents—especially harder-to-reach ones—on how to navigate online health portals and other services.

Though this isn’t a traditional component of promotoras’ work, it is in the social and financial interests of health departments to have digitally literate patients. While many promotoras have advanced digital skills, others still need training and support from their employers. Reorienting health systems toward digital inclusion can have lasting health and equity impacts throughout the region.

In this effort, the city also worked with the University of Texas School of Public Health to develop a trail system that would encourage more active lifestyles. According to the city manager, ISPs can use the trail system’s land as right-of-way to deliver broadband to underserved areas.

Similarly, the city and the Brownsville Community Improvement Corporation demonstrated their commitment to the region’s entrepreneurial tradition by pooling their resources to create a downtown innovation hub. The hub will support digital opportunities for entrepreneurs to attract private capital and incentivize development of faster and more reliable broadband infrastructure. In a major sign of support, the U.S. Department of Commerce awarded $900,000 to support the hub’s launch. The hope is to foster and retain local talent by empowering promising entrepreneurs.

Building off these efforts, in late 2019, the city partnered with the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas to develop a community strategy for broadband implementation in underserved areas. Several community entities have already partnered to fund a broadband feasibility study.

Brownsville presents a clear lens for understanding how acutely the digital divide impacts communities with rural populations and higher shares of foreign-born individuals. Even with such vast disparities, Brownsville shows how building a system of trust and a platform for growth can begin the process of bridging digital divides—in the time of COVID-19 and beyond.

Commentary

Trust and entrepreneurship pave the way toward digital inclusion in Brownsville, Texas

April 8, 2020