Donald Trump becomes the 45th president of the United States on January 20, following a hard-fought election campaign in which Russia featured prominently. What will he mean for U.S.-Russia relations, now at their lowest point since the end of the Cold War? Expect a change in tone. Whether that is matched by a change in substance remains to be seen.

A troubled tone

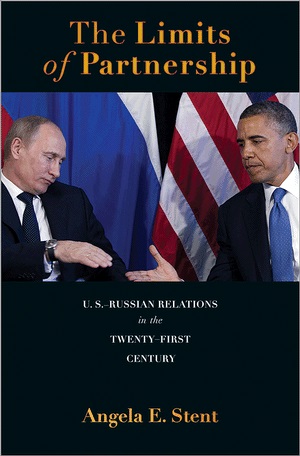

For the leader who launched the reset in 2009, President Barack Obama cannot be happy about where the U.S.-Russia relationship ended up. Following the 2012 presidential elections in Russia and the United States, the White House hoped for modest gains in the relationship. Those hopes were dashed and relations nose-dived following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its instigation of armed separatism in eastern Ukraine.

Things became personal with Vladimir Putin. The Russian president has a thin skin and reportedly was furious when Mr. Obama in August 2013 compared him to “the bored kid in the back of the schoolroom.” (Mr. Obama called Mr. Putin out for what appeared a calculated pose of disrespect at an earlier joint meeting with the press.)

In March 2014, Mr. Obama referred to Russia as “a regional power that is threatening some of its immediate neighbors—not out of strength but out of weakness.” For Mr. Putin, who wants Russia to be seen and respected as a great power, those words cut. Over the past two years, he has shown little interest in engaging his American counterpart. In his December 23 end-of-year press conference, he could not resist mocking Mr. Obama and the Democratic Party in general.

R-e-s-p-e-c-t

That will change in January. Mr. Trump has long taken a more respectful tone toward the Russian leader. In October 2007, he said Mr. Putin is “doing a great job in rebuilding the image of Russia and also rebuilding Russia period.” In December 2011: “I respect Putin and the Russians.” This September: Putin “has been a leader far more than our president has been.”

All that appeals to Mr. Putin’s ego. Moreover, Moscow undoubtedly has paid attention to what Mr. Trump said during the campaign. He has talked of improving relations without calling for Russia to end its more egregious misbehavior. He has suggested he might recognize Crimea’s illegal incorporation into Russia and lift the economic sanctions that the United States imposed with the European Union to press Russia to change its policy toward Ukraine. He has raised questions about NATO, implying that he might seek to revise the terms of the alliance. And he has called into question the U.S. intelligence community’s judgment that the Russian government was behind the release of the Democratic National Committee’s e-mails. If one is sitting in the Kremlin, what’s not to like?

It is less clear what the Russian president thinks of his soon-to-be American counterpart. Some reports are not particularly flattering, e.g., one story in the Huffington Post asserted that the Russian leader regards Mr. Trump as a weaker and more ignorant version of Neville Chamberlain.

In any case, the Kremlin is holding the door open for better relations in the new year. That explains Mr. Putin’s decision not to retaliate for the measures announced by the White House on December 29, including the expulsion of 35 Russian diplomats.

Substantive change?

An improved tone to U.S.-Russia relations could be useful, but the larger question is whether that would be matched by a change in substance. Many of the statements made by Mr. Trump during the campaign put him at odds with the views of the Republican mainstream in Congress, his vice president-elect, and his nominee to become secretary of defense. How will the Trump administration resolve those contradictions?

The president-elect has spoken of his interest in doing deals. Presumably, he wants to do good deals that he can defend as advancing U.S. interests. That may prove difficult.

Start with Russia-Ukraine. Mr. Trump could decide to lift sanctions on Russia and recognize Crimea’s annexation. Those steps would undoubtedly lead to a better relationship with Russia, but what would he get for it? Mr. Putin and senior Russian officials have said nothing to suggest that they are prepared to give something in return that would justify Mr. Trump’s actions. By all appearances, the Kremlin seeks to maintain a simmering conflict in eastern Ukraine to put pressure on Kyiv. And the official Russian position is that the United States should not only lift sanctions but provide Russia compensation for their impact.

Another issue of U.S.-Russian dispute is Syria. Here, also, a good deal may be hard to find. Mr. Trump has said he would like Russia to join with the United States in fighting ISIS. The Russians claim they are already doing that, though relatively few Russian air missions target ISIS. Mr. Trump could accept the Assad regime and cut off support to the more moderate rebel groups, but in return for what? A promise from Moscow that it would fight harder against ISIS, a promise that might later be forgotten?

A third issue is arms control, where the dialogue between Washington and Moscow has been stalemated for four years. Despite his recent tweets about expanding U.S. nuclear capabilities, Mr. Trump’s views on this issue remain a mystery. Doing an arms control deal might interest him, but he would almost certainly have to get into issues such as missile defense, which could provoke questions among Republicans on Capitol Hill.

None of this is to say that a change in the substance of U.S.-Russia relations is impossible, just that it will require policy changes on both sides and will not happen overnight. We may see the tone of the relationship shift after January 20—and that would be a good thing—but real change that moves the relationship to a more positive place will not prove so easy to realize.

Commentary

Trump and Russia: Expect a change in tone. But in substance?

January 4, 2017