What’s going on in the “Heartland?” Two years after a national election that many said pitted America’s interior against the rest of the nation, understanding the region has only gotten harder.

How do we define the Heartland region?

By Ross DeVol

Answering this question isn’t easy. George Strait sings about it. Kevin Costner built a baseball field in the middle of it. The Pioneer Woman cooks for it. Likewise, when one hears the phrase “American Heartland,” specific images and cultural values come to mind. And yet, a widely shared vision of what geographic region truly comprises the American Heartland has so far proved elusive.

In fact, last year when The New York Times asked its readers to choose from nine different U.S. “Heartland” maps depicting the Midwest, the Rust Belt, the “Breadbasket,” and other geographies, no map received more than 22 percent of the vote. Nor has the concept grown any less elusive for all the discussion about the region since then.

To address the confusion, the Walton Family Foundation published a short report earlier this year (which informed the newly released factbook) that advanced a modern, state-based definition of the region.

The Walton definition takes its cue from definitions of the word “heartland” and goes from there. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a heartland as “a usually extensive central region of homogeneous (geographic, political, industrial, etc.) character.” Narrowing down from the generic definition, The Merriam-Webster Dictionary adds a sociopolitical context to Heartland, deeming it “the central geographic region of the United States in which mainstream values or traditional values predominate.” The Merriam-Webster definition also implies that some Southern states are part of the Heartland.

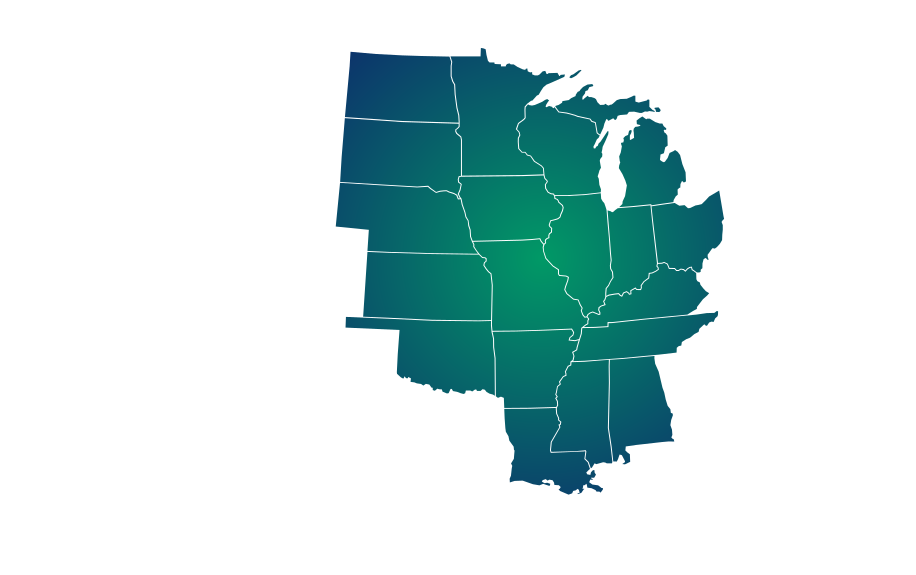

Building on those hints, the Walton analysis assembles an expansive Heartland built on states that begin with the classic Midwest, includes parts of the South, but excludes both the original 13 American colonies and the Intermountain West (and so excludes West Virginia, once a part of an original colony: Virginia).

The Walton Heartland is a mashup of all or most of four different U.S. Census Bureau regions: East North Central (Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin); West North Central (Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota); East South Central (Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi); and West South Central (from which Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana are included). We acknowledge that there’s a good case for adding Texas to the map but we did not do that for the factbook.

As defined here, the Heartland consists of nearly 1.1 million square miles—roughly one-third of the national landmass—sprawling across 19 mostly inland states.

As such, the Heartland region constitutes a cross-cutting middle of the nation with an economy that is bigger than Germany’s and is just a bit smaller than Japan’s—the fourth largest economy in the world.

Ross DeVol is a Walton Fellow at the Walton Family Foundation and a co-author of the new Metro Program / Walton Family Foundation “State of the Heartland: Factbook 2018.

In fact, the proliferation of “red vs. blue” maps and apocalyptic talk-show punditry has, if anything, made it harder to assess the region as we head to another election.

Instead, the national debate purveys conflicting, often-distorted images that portray the region either as a vast “flyover” interior where jobs have disappeared and anger is pervasive, or as an idyllic expanse of wheat fields and mid-sized cities filled with startups.

To be sure, some of the “hot takes” have their truth. But what is really needed by all is a fuller, fairer understanding of the Heartland’s true situation. Such a chronicle—by the numbers, with an agreed-upon geography—might actually help in promoting understanding and supporting conversations about the way forward.

Which is the point of our new State of the Heartland: Factbook 2018. Published as a partnership of Brookings with the Walton Family Foundation, the report is intended to help Heartland and non-Heartland leaders, changemakers, and citizens get on the same page about the region’s current condition and its trajectory at a time of too much division.

An updated view of the Heartland

The indicators presume the fundamental importance of economic vitality to regional, social, and cultural health. As such, the factbook’s indicators first cover nine aspects of the region’s topline outcomes in the search for growth, prosperity, and inclusion. After that, 17 indicators are used to benchmark the region’s standing on four sorts of drivers of strong outcomes. (See page 10 of the full report for a snapshot of the factbook’s 26 economic indicators.)

A nifty interactive tool developed by our colleague Alec Friedhoff allows for easy exploration of the region as a whole and its states, metropolitan areas, and smaller communities.

What do the indicators say about the region? Three major takeaways emerge clearly from the analysis:

1. The Heartland economy is doing better than is sometimes portrayed.

Growth measured by job and output growth have been steady, if not stellar, since 2010 with 19 of the 19 Heartland states adding jobs and 18 increasing their output. Prosperity has also been slowly rising as all 19 states enjoyed increased standards of living, all 19 posted increases in average wages, and 12 saw productivity increases. Supporting all of this is an impressive base of crown-jewel export industries, in particular strong concentrations of advanced manufacturing in the eastern Heartland and of agribusiness in the western Heartland. Overall, the 19 Heartland states—starting with Indiana and Michigan—constitute a manufacturing and export powerhouse that outperforms the rest of the country on more than one-quarter of the factbook’s metrics.

2. The Heartland, however, is not monolithic: Its economy varies widely across place.

In this regard, the region is a checkerboard of sub-regions, states, and local communities where some Heartland places are thriving while others are deteriorating—just as in other regions. On multiple measures, a stark gap exists between the performances of the Western and Eastern Heartland. Labor force participation, for example, remains at crisis levels in the Eastern section, while the Western labor markets are some of the tightest in the nation. Similar divides run north to south. For example, while most Northern states are in the top half of states on measuring human capital and innovation, most Southern ones are among the bottom 10. Likewise, when looking at Heartland sub-regions, the Plains in general is performing quite well, while areas such as the Black Belt (running through Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama), Appalachia, and Indian Country struggle with an emergency of elevated poverty (shared by minorities throughout the region) and high rates of obesity and addiction. Additionally, Heartland metropolitan areas are doing better in general than the region’s rural areas. While large and medium-sized metro areas in the region grew slightly, small towns and rural areas lost population.

3. Serious deficits in the Heartland’s human capital and innovation capacity pose the most serious challenges to improving future prosperity.

On this front, the factbook’s indicators depict a region that is—in most places—struggling to amass the human and technology capacity needed to support broad-based prosperity in the future. Regarding the region’s human capital, only the Dakotas added population as fast as the rest of the nation, meaning that slow population growth—including among prized young workers—limits the region’s overall growth prospects. Worse, only three Heartland states exceeded the average B.A. attainment for the rest of the country, meaning that most places and populations in the region may be unprepared for an increasingly digitalized labor market. Turning to the region’s innovation assets, weak R&D flows, a thin roster of top universities for tech transfer, and a near-complete dearth of venture capital (VC) investment (outside of Chicago) leave Heartland firms starved of the new ideas, new practices, and funding leveraged by firms elsewhere to drive competitive breakthroughs. Finally, lower levels of urban dynamism and epidemics of obesity and opioid use represent substantial drags on productivity and output. These deficits represent the most challenging findings of the factbook and pose the greatest problems in need of solution.

Table 1. Educational attainment in Heartland, 2010-16

| Share of adults with a BA or higher, 2016 | Share change, 2010-16 | |

| Heartland | 28.1% | +2.9% |

| Non-Heartland | 32.6% | +3.1% |

What do these findings suggest for future discussion and action? Above all, the starkness of the region’s human capital and innovation challenge underscores that strategies to increase the region’s education levels and expand its innovation activities should be top-of-mind when Heartland leaders gather to talk about the Heartland’s future. The reason for this is clear: The human and innovation capacities of places are now the core drivers of long-term prosperity. Or, as one of us has noted, the states and regions that build human capacity and invest in and nurture innovation will establish ecosystems that create high-quality, broadly-shared growth for their citizens while attracting migrants from elsewhere, boosting growth further. The good news is that even in its most challenging areas for improvement, the Heartland boasts some of the most impressive and impactful collaborations anywhere of business, civic, and government innovators working together to solve problems.

As for all of us, whether we live in the Heartland or in the rest of the country, there is much at stake. A Heartland that can unlock its fullest potential will also help unleash America’s.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The American Heartland is doing better than prevailing narratives, but serious challenges remain

October 25, 2018