In testimony to the House Small Business Committee at a hearing titled, “U.S. Trade Strategy: What’s Next for Small Business Exports?,” Joshua Meltzer discusses the implications of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) for U.S. and small business exporters.

Introduction

Chairman Graves, Ranking Member Velázquez, honorable members of the committee, thank you for this opportunity to share my views with you on U.S. trade strategy and what’s next for small business exporters.

In 2011, it became clear that concluding the WTO Doha Round in its current form is not possible. Efforts are therefore underway to make progress on parts of the Doha agenda and the U.S. is taking the lead in areas such as services liberalization.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations are the only other trade negotiation to which the U.S. is a party. The TPP has the potential to be the building block for a wider Free Trade Agreement of the Asia-Pacific Region (FTAAP) – a goal endorsed by APEC Leaders at the 2006 APEC Summit in Hanoi. U.S. Trade Representative Ron Kirk reiterated this goal for the TPP at the most recent round of TPP negotiations in Dallas this week.[1]

Given the focus of the current administration on trying to complete the TPP negotiations this year and what appears to be good progress so far, I will focus the rest of my testimony on the implications of the TPP for the U.S. and small business exporters.

The TPP builds on the original P4 Agreement between Brunei, Chile, Singapore and New Zealand which came into effect in 2006. In 2008, the Bush administration notified Congress of its intention to negotiate an FTA with the P4 countries. In the same year, Australia, Peru and Vietnam joined what is now known as the TPP and Malaysia joined the negotiations in 2010.

Concluding the TPP will have important economic and strategic benefits for the U.S. These benefits need to be understood in light of the TPP as a template for a future Free Trade Agreement of the Asia Pacific, where the gains to the U.S. will increase as more countries join the partnership.

The Economic Benefits to the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership

The Asia-Pacific region is of crucial importance for the U.S. It is the fastest growing region in the world and a key driver of global economic growth. Indeed, the region already accounts for 60 percent of global GDP and 50 percent of international trade. And the Asia-Pacific region is expected to grow by around 8 percent this year.[2]

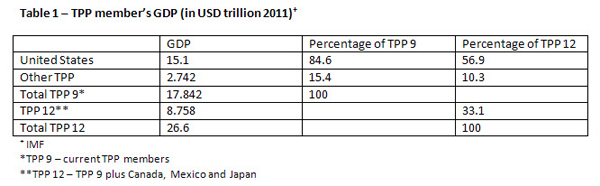

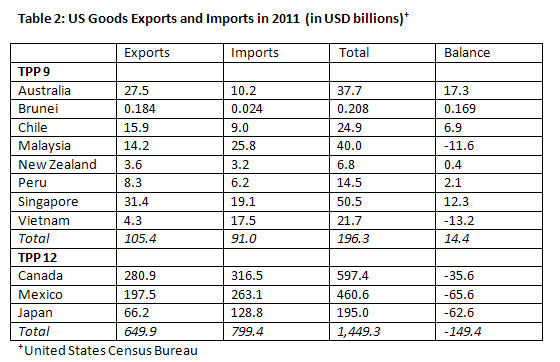

In 2011, the TPP countries had a total GDP of $17.8 trillion, of which almost 85 percent comprised the U.S. economy (see table 1 below). U.S. exports to current TPP members were worth approximately $105 billion in 2011, and imports were valued at $91 billion, meaning that the U.S. had a trade surplus with current TPP member economies of almost $14 billion (see Table 2 below). These trade flows represent approximately 5 percent of total U.S. trade.

Economic modeling estimates that the benefits to the U.S. from the TPP will be $5 billion in 2015, rising to $14 billion in 2025.[3] However, the economic benefits are likely to be larger as this figure does not capture the impacts from investment liberalization under the TPP. Yet, the economic benefits for the U.S. from concluding the TPP negotiations with the current members will be limited by the market access the U.S. already has under its existing free trade agreements with Australia, Chile, Peru and Singapore. Moreover, already low U.S. tariffs on imports limits the gains to the U.S. since the main benefits from trade liberalization accrue to the country liberalizing its trade.

However and as noted, the economic benefit for the U.S. of the TPP needs to be viewed in terms of it being a pathway towards a FTAAP. In this respect, Canada, Mexico and Japan have already expressed interest in joining the TPP. It is unclear at this stage whether these countries will join the current negotiations or accede to a completed TPP. In either event, the addition of Canada, Mexico and Japan would significantly increase the size of TPP GDP to $26.6 trillion, making it much more important in economic terms for the U.S. Such a TPP agreement would cover almost $650 billion of U.S. goods exports and over $800 billion of US goods imports, representing approximately 40 percent of total U.S. trade.

The US also stands to grow its services trade under a TPP agreement. There is limited data on services trade with Brunei, Peru and Vietnam but for the other five TPP members U.S. services exports in 2010 were $28.9 billion and services imports were $13.5 billion, leaving the U.S. with a services trade surplus of $15.4 billion. Including Canada, Mexico and Japan in the TPP would lead to the TPP covering US services exports worth $148.3 billion and services imports of $76.4 billion. The gains to the U.S. from these countries’ participation would also double.[4] And should the TPP evolved into an FTAAP, the gains to the U.S. in 2025 would increase to around $70 billion.[5]

The Impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership on Small Businesses and the Manufacturing Sector

The TPP should lead to increased opportunities for growth for American small business exporters. As a starting point, the TPP will increase U.S. GDP and exports, and these benefits will increase as more countries join. In fact, under a FTAAP, U.S. exports of manufactured goods are expected to increase by almost $120 billion and services exports are expected to increase by almost $200 billion.[6]

The TPP’s impact on American small businesses and the U.S. manufacturing sector can also be inferred by looking at the impact of other free trade agreements. For example, under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)[7] and the U.S.- Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR),[8] the U.S. has a trade surplus in manufactured goods of $12 billion and $3 billion, respectively.[9] In addition, U.S. exports of manufactured goods to NAFTA and CAFTA-DR countries are growing faster than imports.

These figures demonstrate that the U.S. manufacturing sector is world class and highly competitive, and in many sectors the U.S. already operates behind low tariff barriers. Moreover, competition from abroad has also driven U.S. productivity gains and has enabled American manufacturers to source inputs from the lowest cost providers, further enhancing overall competitiveness. Further trade liberalization under the TPP is therefore likely to provide additional opportunities for the U.S. manufacturing sector overseas.

U.S. small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) also stand to gain from trade liberalization. In fact, almost 98 percent of all exporters and 97 percent of all importers are SMEs, representing almost 40 percent of U.S. goods exports and 31.5 percent of goods imports.[10] In addition, 94 percent of SMEs are exporters and importers. Therefore, trade agreements that liberalize trade barriers, like the TPP, should disproportionately benefit SMEs. In contrast with large businesses, SMEs generally benefit the most from government efforts to reduce trade barriers overseas as their capacity to overcome these barriers by establishing subsidiaries in other countries is much more limited.

Setting the Trade and Investment Rules for the Asia-Pacific Region

The economic gains to the U.S. from the current TPP members highlight the significance of the TPP as a template for further economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region. As the TPP is an ongoing negotiation, the details of what is being proposed have not been released. However, we do know that the recent Korea-U.S. FTA will be a baseline and that USTR is seeking agreement on a range of new rules. For instance, in addition to including rules such as on goods and services, non-tariff barriers, investment and intellectual property, the United States is seeking to include new rules on regulatory coherence to reduce trade barriers arising from unnecessary regulatory diversity among TPP member countries. The U.S. is also seeking rules on state-owned enterprises in order to discipline the trade distorting impact that they can have when they do not operated according to competitive market-based principles.

The TPP should also address the realities for American businesses that rely on supply chains located in different countries, often in the Asia-Pacific region. Developing coherent rules of origin is one way of ensuring that the TPP reflects these business realities. Progress on trade facilitation rules which reduce the costs of moving goods through customs is another important one.

The TPP can also provide an important framework for the U.S. to promote rules that can protect the free flow of data across borders. The internet has become a key driver of trade, especially for SMEs, as companies have been able to use the internet to access customers overseas and at scale.[11]

Getting these rules right is important as they will establish the framework for trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific region. A rules-based trading system backed by an effective dispute settlement mechanism, which increases market access and the certainty and predictability of international trade and investment, will reduce risk and facilitate U.S. and global growth.

Deepening U.S. Economic Integration in Asia

The TPP will also address the trend in the Asia-Pacific region toward regional economic integration that excludes the United States. For instance, ASEAN has free trade agreements with China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. And economic cooperation among ASEAN +3 (ASEAN, China, South Korea and Japan) has been closed to U.S. participation. China, South Korea and Japan are also considering a trilateral FTA. These agreements divert trade from the United States and the absence of U.S. participation in developing these trade rules undermines American leadership in the region. Recent U.S. membership in the East Asian Summit (ASEAN+3, Australia, New Zealand, India and Russia) should go some way toward addressing this problem, but the U.S. has so far not pursued economic integration in the EAS. In this light, the TPP will be an important vehicle for the U.S. to pursue economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region.

Completing the TPP will be an economic complement to President Obama’s declaration of a U.S. strategic “pivot” toward Asia.[12] It will build on the Korea-U.S. FTA which came into effect on March 15, 2012. As Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said recently, “One of the most important tasks of American statecraft over the next decade will therefore be to lock in a substantially increased investment – diplomatic, economic, strategic, and otherwise – in the Asia-Pacific region.”[13]

Conclusion

At the APEC Summit in Hawaii last year, President Obama said that “the TPP has the potential to be a model not only for the Asia Pacific but for future trade agreements”. This message underlies the need to assess the benefits to the U.S. of the TPP in both economic and broader strategic terms. In economic terms, the gains from completing the TPP with the current members will be positive but small for the United States. However, should the TPP become a template for regional economic integration then the gains to the U.S. from broadening out the TPP will be significantly magnified.

The strategic benefits stem from the TPP as a vehicle for further economic integration in the Asia-Pacific region. In this sense, the relatively small immediate economic benefits from liberalizing trade with the current TPP members should not obscure the importance of designing the rules of the game, so to speak, for trade and investment in what will likely be the most dynamic and fastest growing region of the world over the coming decades. From this perspective, the rules rule, and new disciplines in areas such as state-owned enterprises and regulatory coherence— in addition to the more traditional rules on goods, services, investment and intellectual property— will ensure that economic growth in Asia remains market orientated, largely open and non-discriminatory. It is only under these terms that U.S. trade with the Asia-Pacific region should be expected to prosper for the years to come.

Commentary

TestimonyThe Significance of the Trans-Pacific Partnership for the United States

May 16, 2012