Democracy is facing deep challenges across Latin America today.

On February 16, for instance, municipal elections in the Dominican Republic were suspended due to the failure of electoral ballot machines in more than 80% of polling stations that used them. The failure sparked large protests around the country, where thousands took to the streets to demand explanations and to express their discontent with the Junta Central Electoral (JCE), the Caribbean nation’s electoral body. This has not only left the country in a deep political crisis, but has led citizens to lose trust in democratic institutions.

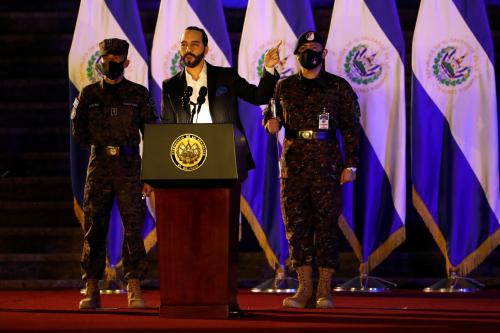

Another country facing a democratic crisis in the region is El Salvador. On February 9, thousands of Salvadorians gathered outside the country’s legislative assembly as the country faced its most significant constitutional crisis since signing a peace agreement to end the civil war in 1992. The crisis started when President Nayib Bukele called the country’s legislators to an emergency session to approve a $109 million loan for the third phase of his security plan, called the Territorial Control Plan. After legislators rejected the plan, the president called military officers into the chamber. The president of the assembly called the show of force an “attempted coup” that threatened the separation of powers in the country and disregarded core democratic institutions.

On January 5, the authoritarian regime of Nicólas Maduro in Venezuela orchestrated what opposition officials called a “parliamentary coup” against Juan Guaidó, with police forces blocking the opposition leader from entering the National Assembly to elect the president of the parliament. This clearly exposes the regime’s strategy to dismantle the last legitimate organ among the country’s constitutional powers.

Finally, there have been violent protests and social movements in Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Chile.

These recent examples show that democracy in Latin America is facing a critical period, as a report from International IDEA — “The Global State of Democracy 2019: Addressing the Ills, Reviving the Promise” — details. The report examines the state of democracy globally, observing that while democracy continues to expand, its quality is rapidly deteriorating and threats to democracy are rising. It shows that democracy remains resilient, with a high level of citizen support, while emphasizing that most of the attacks on democracy are not external but internal.

Never in the last four decades has the future of democracy been as threatened as it is today. In general, the four main risks to democracy are: reduced space for civic action, weakened democratic checks and balances, high levels of inequality, and attacks on human rights. In Latin America, in particular, many of these challenges are acute, but overall the picture is mixed.

The state of democracy in Latin America

The research shows a regional outlook with bright spots and shadows, along with diversity among countries when it comes to the quality of democracy.

While some democracies, such as Uruguay and Costa Rica, are among the best in the world, others — for example, Brazil — have experienced democratic erosion in recent years. Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, Paraguay, Bolivia, and the Dominican Republic, meanwhile, all present different degrees of democratic fragility. Nicaragua is experiencing a serious democratic backsliding, while Venezuela is suffering a total democratic breakdown. These two countries, together with Cuba, are the region’s three authoritarian regimes.

It’s important to identify both the positive trends in Latin American democracies and the main challenges they face.

The most notable positive aspects are:

- In the last 40 years, Latin America made the most significant gains worldwide, becoming the third most democratic region in the world, after North America and Europe.

- The vast majority of the democracies in the region have displayed notable resilience: Only 27% experienced any interruption in these last 40 years.

- Latin America has made major gains in the electoral sphere — indeed, elections are popularly accepted as the only legitimate means of coming to power — and the region has the highest levels of election participation in the world, with a regional average of 67%.

- While much remains to be done, it is the region with the highest percentage of women parliamentarians in the world, with a regional average of 27%. However, there is currently no female elected Latin American president. In Bolivia, which went through a political crisis after the annulment of presidential elections, Jeanine Añez has been designated as the country’s interim president.

There is a long list of challenges as well, including:

- Four decades after the beginning of the third democratic wave, the region is showing signs of democratic fatigue. According to Latinobarómetro, overall support for democracy fell to 48%, the lowest level in recent years, while indifference between a democratic regime and an authoritarian one climbed from 16% to 28%. Dissatisfaction with democracy increased from 51% to 71% between 2009 and 2018.

- The crisis of representative democracy is worsening. Trust in the legislatures is at a mediocre 21%, whereas trust in political parties has plummeted to an anemic 13%.

- The region still has the highest levels of income inequality in the world: Of the 26 most unequal countries in the world, 15 (58%) are Latin American.

- The region is also in third place, after Africa and the Middle East, on corruption; it has the highest levels of crime and violence in the world; and despite numerous reforms, weak rule of law continues to be an Achilles’ heel of democracy in the region.

- Importantly, approval ratings for the governments have been falling significantly and steadily in the last decade. At the same time, there is a heightened citizen perception that the elites govern to benefit a privileged minority of society.

Overcast times in Latin America: What should be done?

The year 2020 is expected to see overcast times in Latin America, with conditions equally or even more complex and volatile as in 2019. Political risk consultancy the Eurasia Group names social discontent in the region as one of the top 10 political risks in the world in 2020. Additionally, according to The Economist’s 2020 instability risk map, the most vulnerable countries are, in addition to Venezuela and Haiti, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Brazil, Honduras, Chile, Mexico, and Paraguay.

As it enters the new year and a new decade, therefore, Latin America is marked by “irritated democracies,” characterized by anemic economic growth, citizen frustration, social tensions, discontent with politics, and weak governance. There is significant fear that 2020 will be another challenging year for the governments of Latin America.

Social discontent and instability will continue. The middle class, dissatisfied with the status quo, feels vulnerable and is demanding more social spending by their governments. Such spending, in turn, reduces governments’ ability to implement the adjustment measures that the International Monetary Fund and private investors demand as a condition before delivering fresh loans and/or investments. Moreover, citizens have lost patience, are less tolerant of their governments, are more demanding of their own rights, and are hyper-connected via social networks.

As the International IDEA report stresses, we should “address the weaknesses of democracy and revive its promise” with a renewed agenda that lays the basis for a democracy of a new generation. Such a renovation must be aimed at improving democracy’s quality and resilience, as well as strengthening its institutions. It must seek to empower citizens, recover economic growth, rethink the development model, and adopt a new social contract. The agenda must make it possible to respond not only to current issues — including poverty, inequality, corruption, insecurity, and weak rule of law — but also the new challenges.

Lastly, the current situation of democratic discontent and social convulsion that Latin America is experiencing requires offering democratic solutions to the problems of democracy in order to avoid a dangerous escalation of strong populist rhetoric, which could end up aggravating the complex regional situation. It is not merely enough to have quality and resilient democracies. We must also strive to build a modern and strategic state, better governance, and political leadership committed to democratic values, transparency, a connection to the people, empathy, and the ability to govern the complex societies of the 21st century.

Commentary

The rapidly deteriorating quality of democracy in Latin America

February 28, 2020