This blog is a summary of comments made during the Congressional staff briefing on Nigeria Abductions: Ending Attacks on Schools hosted by Reps. Conyers, Wilson, and Bass on May 14, 2014.

The mass abduction of girls from their school in Chibok, northern Nigeria has been a wake up call to the international community. It has brought to light the longstanding and deadly conflict in northern Nigeria, the unpredictable safety of schools, and the precarious position of girls as they seek education, especially in conflict settings.

This one horrible situation has galvanized the international community. It is, however, not isolated. It should also be a wake up call to the urgent issue of attacks on education globally.

There are four critical dimensions of attacks on education globally.

First is the scale of attacks on education. In 30 countries globally, schools are regularly attacked. This means more than 1,000 attacks on schools in each of these 30 countries, each year. In 2012, United Nations data reveals 3,643 separate, documented attacks on education in 17 countries. In these attacks, 75 children and 212 teachers were killed or injured. In the same year, there were 90 cases of military occupation of schools in 11 countries.

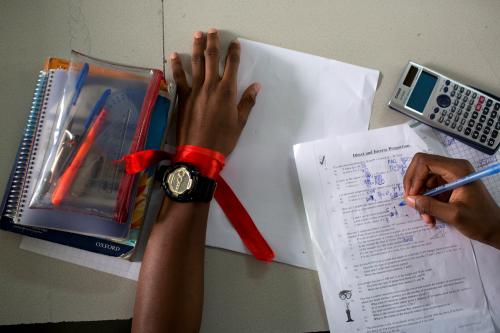

Behind these numbers are experiences of children and families. In 2009, as we did research in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, armed militia burned school benches for their cooking fire on the hill above the school. When we left, they entered the school to sleep. In September 2013, a Syrian mother told us, “Education was a beautiful dream for our children.” But that dream was no longer, as their school has been destroyed. Their school was one of more than 3,000 schools that have been destroyed in Syria since the beginning of the war.

Second is the scope of attacks on education. What are attacks on education? Attacks on education are defined as any intentional threat or use of force against students, teachers, or educational institutions, which are carried out for political, ideological, sectarian, ethnic, religious, or criminal reasons. Attacks may be conducted by state security forces or non-state armed groups. These attacks may be motivated by curriculum content. They may be aimed at curbing educational opportunities for certain groups, such as girls. While the rhetoric is often that schools are “collateral damage” to warfare, the reality is that schools are usually intentional targets.

Third, attacks on education violate human rights and international law. They violate the fundamental right to education, enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. As deliberate attacks on civilians and on civilian objects, they also constitute violation of international law through the Geneva Conventions and are defined as war crimes by the Rome Statues. U.N. Security Council Resolution 1612 states that attacks against schools are a grave violation against children and a violation of children’s right to education.

The Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) was founded in 2010 to isolate attacks from other issues that relate to education in emergencies and focus specifically on the prevention of attacks. Through a broad consultative process, GCPEA has led the drafting of the Lucens Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict. These guidelines urge all parties to armed conflict not to use schools and universities for any purposes related to military effort. Along with the Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statues, they are important international mechanisms for the protection of schools from attack. The Lucens Guidelines will be launched in February 2015 and be ready for endorsement.

Fourth, the abductions in Nigeria, and attacks on schools globally, are symptoms of much larger issues of inequity and lack of human security. Ensuring the right to education involves addressing, and preventing, attacks on education. It also necessitates opportunities to go to school and to learn. More than half of the out-of-school children globally live in settings of armed conflict. One-fifth of these out-of-school children live in northern Nigeria. Compared with children in other low-income countries, children living in conflict are less likely to survive to school age; they more rarely attend school and complete a full basic education; and they are far less likely to access secondary education. Only 79 percent of youth are literate in conflict-affected settings, as compared with 93 percent in other countries. Conflict disrupts teacher training systems, destroys physical infrastructure, and promotes a culture of violence that impacts classroom pedagogy, contributing to poor quality of teaching and learning. Children in conflict who are poor, female, and from ethnic and linguistic minority groups are multiply marginalized, and they go to school and finish school in very low numbers. The abducted children in Nigeria are indeed multiply marginalized: they live in a conflict-affected, rural, marginalized area of the country, and they are girls.

What can the international community do to disrupt these cycles of conflict in Nigeria and elsewhere? My research suggests two primary actions to address the issues.

First is building support around enforcement of the Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statues and the endorsement of the Lucens Guidelines in February 2015.

Second is investing in education to disrupt the cycles of conflict that create the conditions for these types of attack. A military response does not disrupt this cycle. Funding for education in conflict settings is going down. Education was only 1.4 percent of global humanitarian aid in 2012, down from 2 percent in 2011. A minimum of 4 percent is needed to meet needs.

The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) is a promising mechanism for harnessing funding to enable girls and other marginalized children to go to and succeed in school. Formed in 2011 to replace the Fast Track Initiative (FTI), the GPE is an international voluntary coalition organization, comprising almost 60 developing countries, donor countries, international organizations, private companies, nongovernment organizations, and civil society. Its mission is to spur a systematic and coordinated effort to ensure good quality education is delivered to all children, in particular the poorest and most vulnerable children, including girls, in developing countries.

The GPE’s new strategic plan prioritizes settings of conflict and fragility. The number of fragile states funded by GPE grew exponentially, from 1 in 2003 (when it was FTI) to 22 in 2013. GPE works with 14 countries that experience more than 1,000 attacks on education each year. The GPE Replenishment Pledging Event, coming up in June in Brussels, is an opportunity to support increased investment in high quality education in conflict-affected settings like Nigeria.

Return of these school girls to their families is but the beginning of a critical wake up call to the international community to protect education from attack both in urgent situations and proactively through building support around the Lucens Guidelines and international law and though investing in education to disrupt the cycles of conflict that create the conditions for these types of attack in the first place.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Need to End the Nigeria Abductions and All Attacks on Schools Globally

May 15, 2014