The words debt and deficits pop up in nearly every debate about taxes and spending. The concepts are related, but they’re not the same thing. Fans of Barack Obama like to talk a lot about the deficit because it has come down and is low by historical standards. Critics of the president like to talk about the debt because it is very large by historical standards. Here are a few facts to help you follow the arguments:

What exactly is the federal deficit?

The deficit is the difference between the flow of government spending and the flow of government revenues, mainly taxes. With a few exceptions, the deficit is measured in cash outlays and cash receipts.

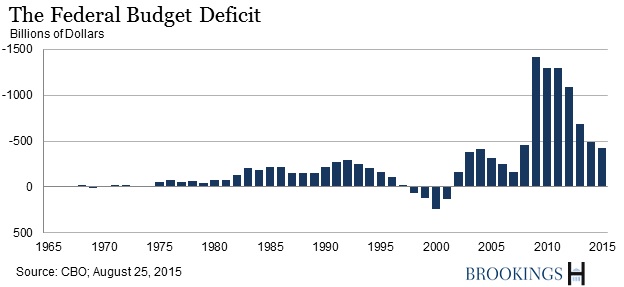

For the fiscal year 2015, which ended September 30, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that total revenues were $3.249 trillion (up 8% from the previous year) and total spending was $3.685 trillion (up 5% from the previous year). The resulting deficit was $435 billion. That compares to $483 billion in the previous year, and, in dollar terms, was the smallest since 2007.

Is that deficit considered big?

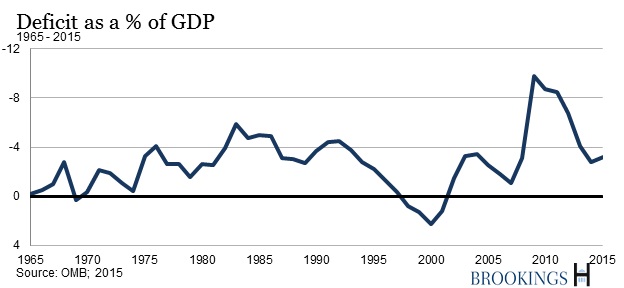

Well, $435 billion is a lot of money. But economists gauge the size of a government’s deficit by comparing it to the size of its economy; obviously a $435-billion is very different in a small economy, say Portugal, than in a big one like the U.S. and, because of inflation, $435 billion today is very different from $435 billion in 1965.

In fiscal year 2015, the federal deficit amounted to 2.4% of the gross domestic product, the value of all the goods and services produced in the U.S. By international norms, that’s a modest-sized deficit. It’s slightly smaller than the average of the past 50 years of deficits in the U.S., and well below the 9.8% of GDP deficit in fiscal 2009 during the worst of the Great Recession. The deficit has come down because the economy has improved (which means more people working and paying taxes and fewer people collecting unemployment benefits and the like), taxes have been raised a bit on upper-income Americans, Congress has been tight-fisted on the spending it appropriates, growth in health-care spending has slowed, and interest rates remain very low. Some economists—former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, among them—say that the deficit came down too fast, and the economy suffered as a result.

So what’s the debt?

The debt is the total amount of money the U.S. government owes. It’s the sums it borrowed to cover last year’s deficit and all the deficits in years past. Each day that the government spends more than it takes in, it adds to the federal debt. When the fiscal year ended on September 30, the U.S. government owed $13.124 trillion to the public (a measure that includes Treasury securities held by the Federal Reserve.) To see the very latest tally, check the Treasury’s “The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It” website.

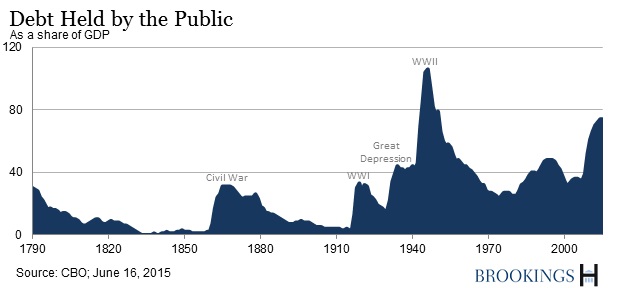

The federal debt was driven up by the big deficits incurred during the Great Recession. At year-end, the debt amounted to a historically large 74% of GDP, a level exceeded only by the levels seen at the end of World War II. Before the recession, the debt held by the public was about $5 trillion or 35% of GDP.

Is debt at 74% of GDP a problem?

For now, it isn’t. The U.S. government is able to borrow at very low interest rates on global financial markets, and there doesn’t appear to be much private-sector borrowing that is crowded out by U.S. Treasury borrowing right now.

However, no one really knows at what level a government’s debt begins to hurt an economy; there’s a heated debate among economists on that question. Many economists think that more private borrowing will be crowded out if the government’s debt remains this large as the economy strengthens. Debt at this level, though, does limit the amount of flexibility the U.S. government has if it confronts another financial crisis or a deep recession and wants to borrow heavily, as it did during the Great Recession. It probably would be hard to add another 35 percentage points of GDP (or $5.7 trillion) to the national debt.

What about the debt ceiling?

Congress has always restricted federal borrowing. Before World War I, Congress often authorized borrowing for specific purposes and specified what types of bonds the Treasury could sell. That gave way to an overall ceiling on federal borrowing in 1917, which Congress has raised repeatedly, often with a lot of political controversy. The ceiling applies to the gross federal debt, both debt owed to the public and Treasury bonds held in the Social Security trust fund. (Economists generally focus on debt held by the public because they think the federal government is best viewed as a financial whole.) The debt limit has been set at $18.1 trillion since March 2015. For the following several months, the federal debt was right at the ceiling, forcing the Treasury to resort to various financial maneuvers to conserve cash and avoid net new borrowing. In early October 2015, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew said the Treasury was likely to exhaust those so-called “extraordinary measures” on or about Nov. 5, and would be left to fund the government with only the cash on hand, which won’t be enough to pay the bills every day.

“Increasing the debt limit does not authorize new spending commitments,” Treasury Jack Lew has said. “It simply allows the government to pay for expenditures Congress has already approved, thereby protecting the full faith and credit of the United States.”

For more, see the Congressional Research Service’s “The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases” (October 1, 2015), the latest from the Treasury, CBO’s latest on the debt ceiling, the GAO’s “Understanding Federal Debt,” and the Bipartisan Policy Center’s frequently updated debt-limit analysis.

What about the future?

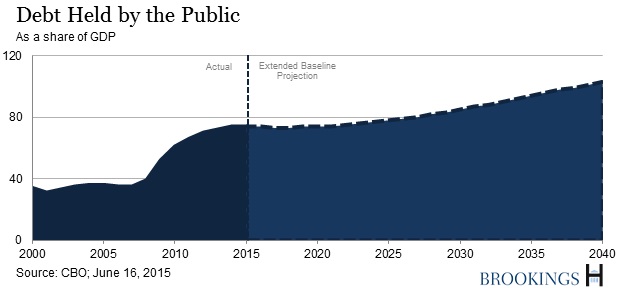

If current policies persist without change—a big “if”—the Congressional Budget Office projects that deficits and the debt (as a percentage of GDP) will be stable for the next several years, but will then turn up again as more Americans become eligible for Social Security and Medicare, as health-care costs continue to grow faster than the economy, and as interest rates rise back to more normal levels. Looking out 25 years, admittedly tricky because there’s so much uncertainty, CBO projects that the federal debt will hit 104% of GDP in 2040 unless Congress changes tax or spending policies before then.

To read more explainers from the Hutchins Center, visit the Hutchins Center Explains series page.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Hutchins Center Explains: Debt and Deficits

October 16, 2015