Editor’s note: A version of this piece was previously published on the BBC website on April 29, 2015.

When it comes to education the differences between the developed and developing worlds remain stark.

There has been a convergence in the number of pupils enrolling in primary school, with many more young children in developing countries now having access to school.

But when it comes to average levels of attainment—how much children have learned and how long they have spent in school—there remains a massive gap.

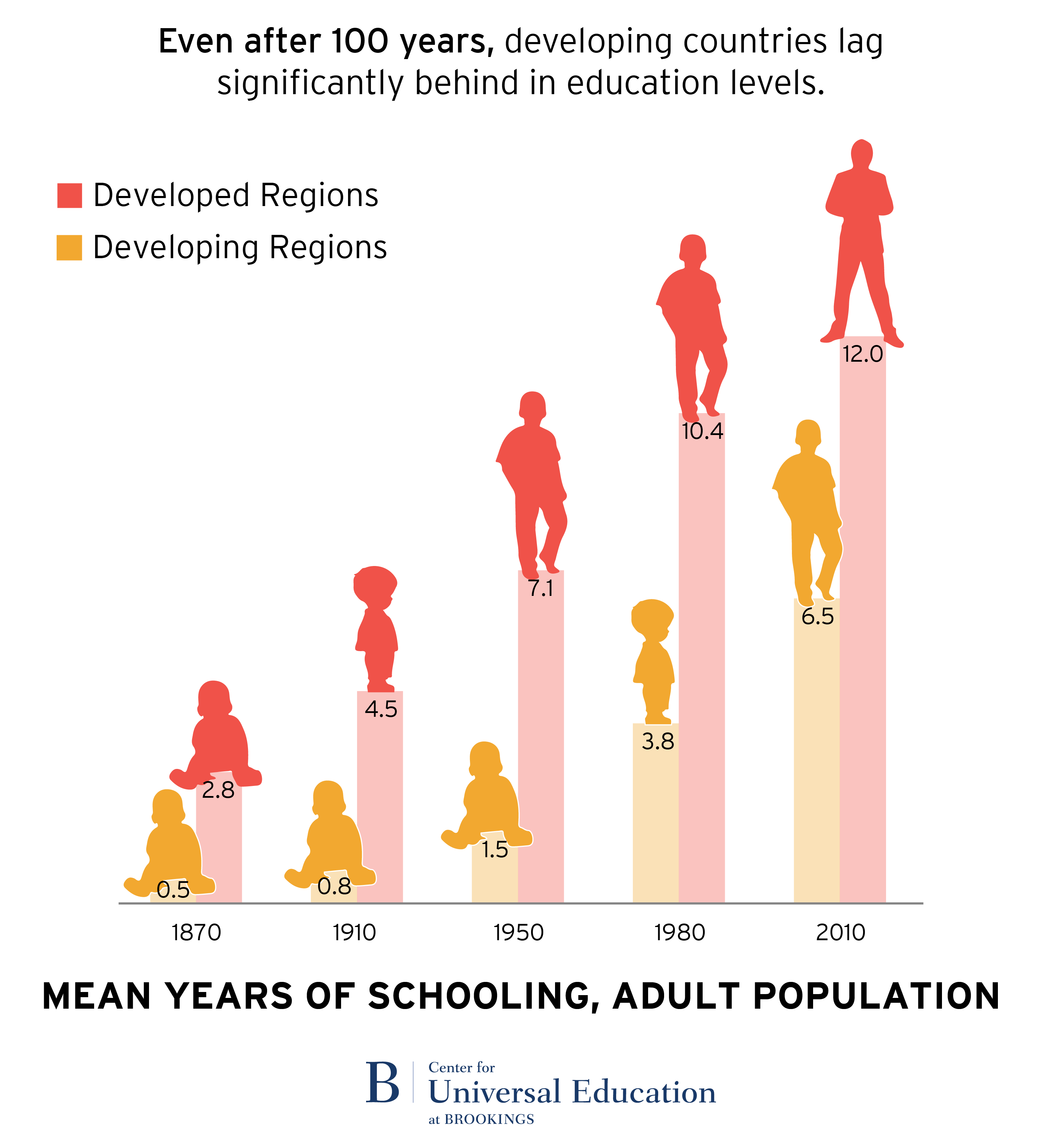

When it’s shown as an average number of years in school and levels of achievement, the developing world is about 100 years behind developed countries. These poorer countries still have average levels of education in the 21st century that were achieved in many western countries by the early decades of the 20th century.

Head start

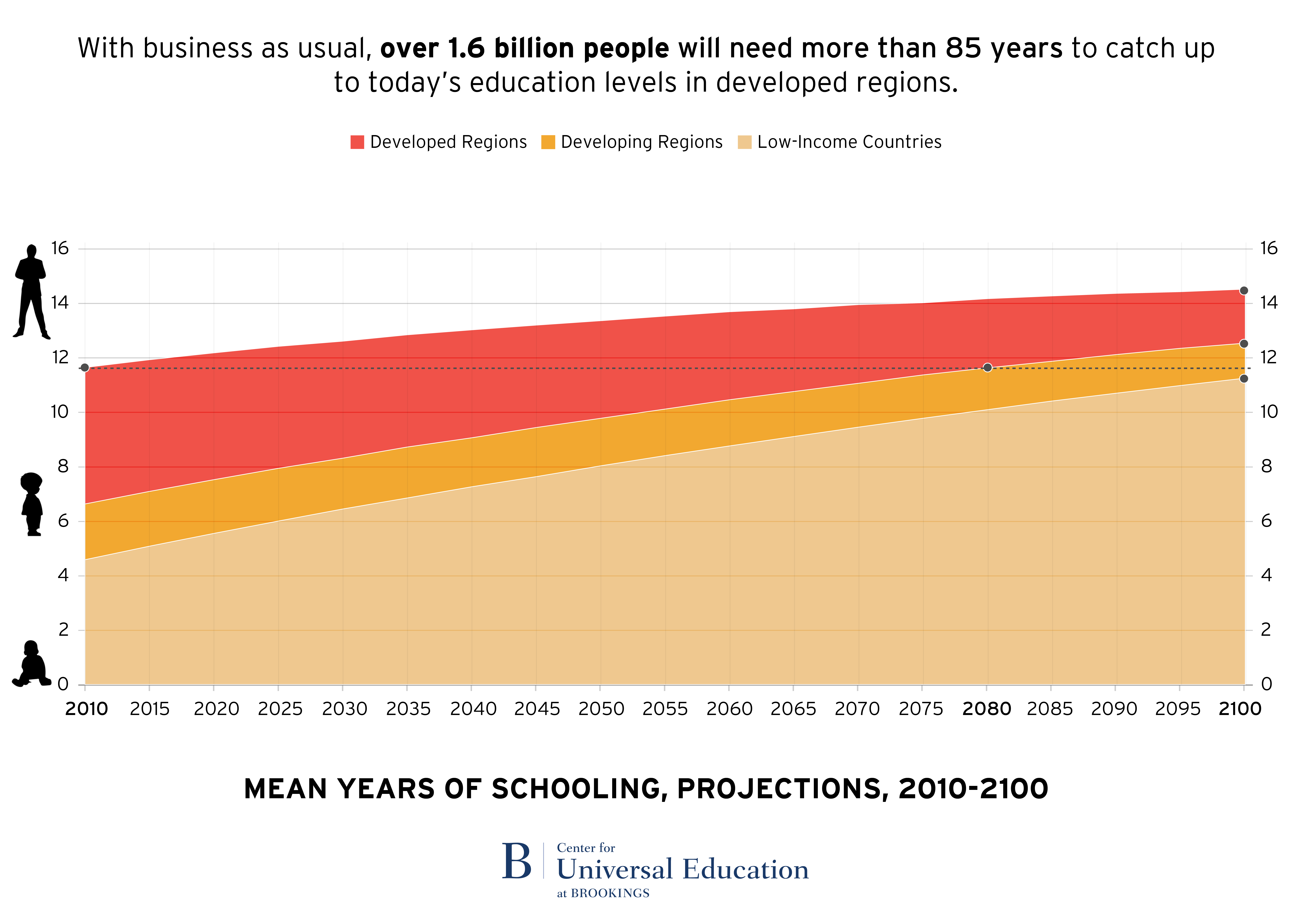

If we continue with the current approaches to global education, this century-wide gap will continue into the future.

Of course this gap varies between different countries and regions—and there are differences within countries.

But there are stark overall differences between the average levels of education between the developing and developed countries—a comparison which uses the U.N. definition of “developed” as Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

This 100-year gap might not be morally acceptable, but from a historical perspective it is understandable.

The idea that all young people, not just those in the elite, should have an opportunity to be educated had spread across Europe and North America by the middle of the 19th century.

It was only a century later, in part spurred on by the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that mass schooling spread across the developing world. It meant that there was a 100-year gap there from the outset.

Within the last 50 years, the pace of progress enrolling children in primary school has been much faster, resulting in 90 percent of the world’s children enrolled in primary school.

Another 70 years

However, when looking beyond primary enrollment, at attainment and learning, the idea of global convergence vanishes. While young people around the world may almost all be enrolling in school they are by no means all learning well and progressing through school.

The education levels of the adult workforce, often measured by average numbers of years of school, is in the developed countries nearly double that of their developing country peers.

In developed countries, adults have an average of 12 years of school, compared with 6.5 years of school for those in developing countries.

This gap is not projected to close any time soon. If we continue with today’s pace of change, it will take at least 65 years for average adults in developing countries to reach 12 years of school and that stretches to 85 years for the adults living in low-income countries.

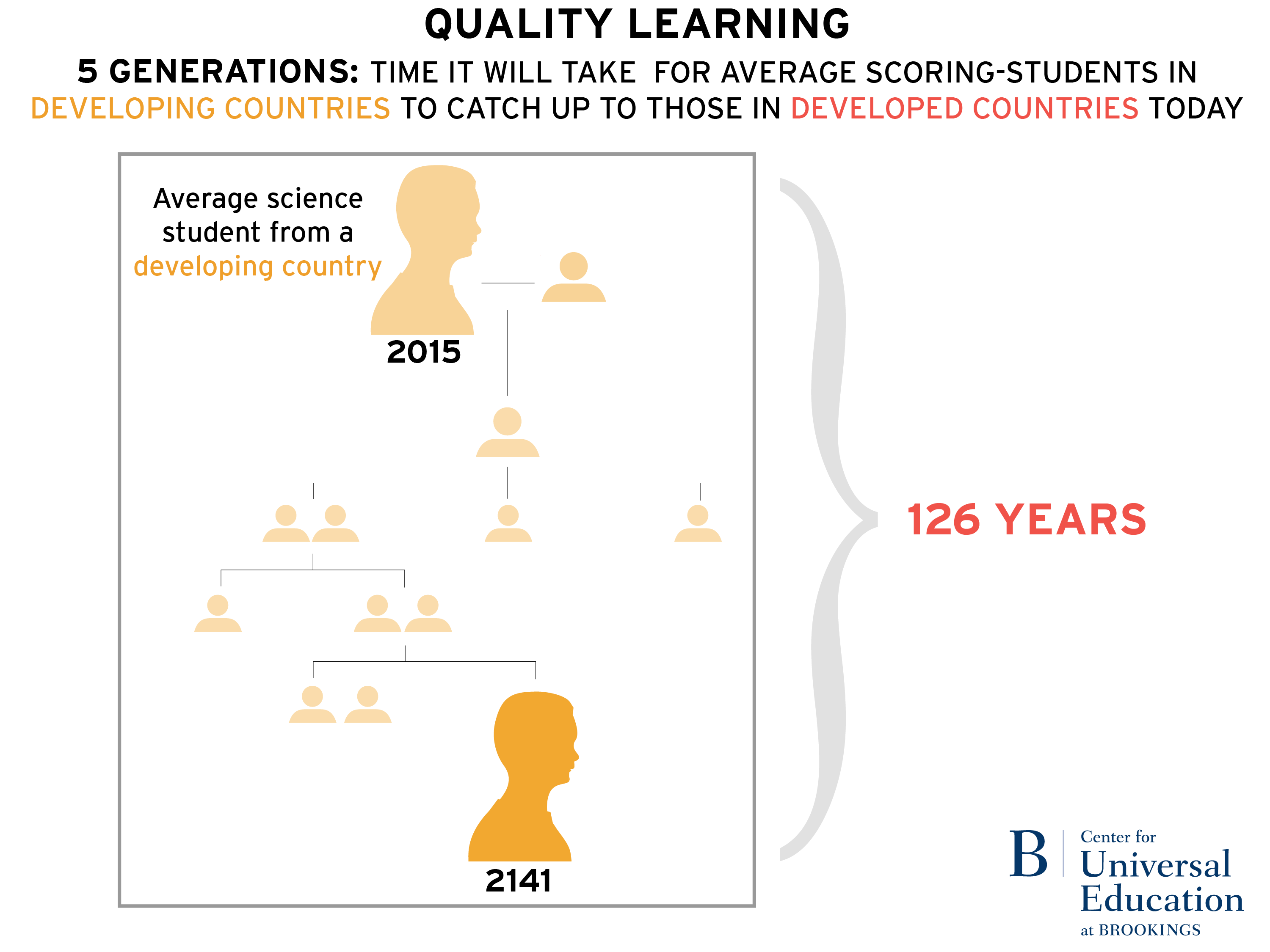

The 100-year gap is also evident in the learning levels between students in developed and developing countries.

According to work done by economist Lant Pritchett, at the current rate of progress, it will take well over 100 years for students in developing countries to catch up to the learning levels in science of today’s developed country students. These predictions admittedly use limited data, but if anything they understate the gap as they do not include the world’s poorest countries that haven’t participated in international exams.

This analysis is a reminder of the urgent need for a rethink on how to make progress in education.

While the 100-year gap may indeed be a 70-year or 125-year gap depending on country or education indicator, the analysis itself is a useful tool to bring attention to the serious inequities in education globally.

But the real question is what can be done to close the gap? Can we speed up progress within the same mass schooling model? Can there be entirely different models that would accelerate change?

Is there a way for education systems to “leapfrog” a few stages forward, such as the way that in some developing countries skipped to using mobile phones without first investing in landline infrastructure. What would be the appropriate role for new technologies in this process?

Can we envision a world where it does not take developing countries 50 or another 100 years to catch up?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The global ‘100-year gap’ in education standards

April 29, 2015