Improving health care in the United States is not an easy venture. With high and rising costs and room for improvement in the quality of care delivered, national, state, and local efforts have engendered a renewed focus on primary care: in particular, person-centered accountable care. And for good reason—investment in primary care makes sense. The 2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey indicated that of the almost 1.1 billion physician office visits each year, more than 560 million (55.5%) were to a primary care physician.1 This figure will continue to rise with coverage expansions from the 2010 Affordable Care Act and the ever-increasing number of eligible Medicare beneficiaries.2 Moreover, for most people, the primary care physician (PCP) is their gateway into a highly technical and complex medical community. It is with their PCP that individuals establish a long-term, trusting relationship, and a focus on accountable primary care fosters health and wellbeing, beyond the provision of sick care.

Many policy initiatives in both the public and private sectors are attempting to forge forward a path to create a healthier America. The 2010 passage of the Affordable Care Act stimulated the formation of more Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), and private payers are engaging practices and hospital systems in ACOs and similar innovative care delivery and payment models. The Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) is one such model that is well-aligned to be an impactful first step in reforming US health care. Recently, the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC), with support from the Milbank Memorial Fund, released a comprehensive report on the current state and future of PCMHs in U.S. health care.

Care Delivery in a PCMH

An exact definition of a PCMH is illusory because the model is continually evolving. Nevertheless, the four major primary care societies designed and endorsed the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home, which outlined the general characteristics of a PCMH. These include:

- Personal physician care

- Physician-directed medical practice

- Whole person orientation

- Coordinated and/or integrated care

- High quality and safety in care

- Enhanced access to care

- Payment that supports enhanced services

Coordinating high quality and safe care across providers with a person-centered focus is the ultimate goal of the physician-led care team in a PCMH. But are PCMHs better than traditional care models? To appropriately answer this question, it is important to assess whether care in a PCMH is better for the patient and whether care in a PCMH is better for the health system at-large. The preponderance of evidence suggests yes to both questions, though more and more-robust studies are necessary to be more-conclusive.

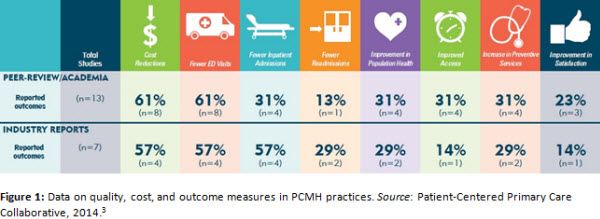

Nevertheless, Figure 1 provides a collapsed view of results from those studies available on how PCMHs fare in terms of quality, cost, and outcomes compared to traditionally operated, fee-for-service practices. PCMHs appear to have the greatest clinical effect (61% reduction via academic reports; 57% reduction via industry reports) in visits to the emergency room, presumably through increased access to the practice in off-peak hours and increased availability of next-day appointments. Similarly, there were fewer reported inpatient hospital admissions (31% and 57% for academic and industry reports, respectively).

For many policy makers, tangible cost reductions are essential for any reform proposal. As such, an approximately 60% reduction in cost was a robust and welcome signal that PCMH models might be a way to help bend the cost curve.

PCMHs Need Accompanying Payment Reforms:

Even with early reports of high quality care and reductions on cost, the PCMH model is unsustainable without proper financial alignment from payment reforms. Currently, many of the core principles of the PCMH are reimbursed poorly, if at all, by Medicare and commercial payers. For example, payment for increased patient education, care coordination, staffing for augmented practice hours and a telephone triage service, and an electronic medical record does not exist and cannot be covered by billing for evaluation and management codes alone. These upfront and enduring costs can readily discourage practices from making the jump to PCMH models.

Transitioning away from fee-for-service reimbursement to new payment models can properly align financial resources with the services delivered. Some examples of new payment models include affixing a per-member per-month payment atop fee-for-service reimbursement; rolling certain fee-for-service codes into a bundled or episodic payment; shared savings arrangements; and partial or full capitation. These models vary in their degree of comprehensiveness, but each begins to pay for the more accountable, person-centered care delivered in a PCMH.

Moving Forward

In order to create a health care system that delivers high value care, a stepwise transition to accountable care principles should be a priority for policy leaders. The PCMH offers one possible solution, and may act as an appropriate intermediate for practices interested in ACO arrangements. However, in order to realize the full potential of PCMHs, the following are important areas which need more attention.

- Improving Patient Satisfaction. Patient satisfaction should be a top priority for any model that is, by name, patient-centered. However, as shown in Figure 1, patient satisfaction is both underreported and underwhelming. A renewed focus on patient-centered efforts will ensure a better overall patient experience.

- Team-based Care. Delivering team-based care is an essential component of any successful PCMH, as productivity and coordination are maximized with a well-aligned care team. Further efforts to change the culture of medical practice from one of autonomy to one of teamwork will likely reap many rewards in terms of quality and savings.

- Physician leadership. Without robust physician leadership, changing the way we deliver and pay for care will be difficult. Engaged, excited physician leaders can propel PCMHs and accountable primary care forward. In addition, clinician satisfaction must be considered in an era of high PCP burnout. Physician leadership in designing and implementing new payment and delivery systems will ensure that those delivering care are satisfied with the structure within which they practice.

References

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 Summary Table s. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2010.

2. Medicare Physician Services: Utilization Trends Indicate Sustained Beneficiary Access with High and Growing Levels of Service in Some Areas of the Nation. Washington DC: Government Accountability Office;2009.

3. Nielsen M, Olayiwola N, Grundy P, Grumbach K. The Patient-Centered Medical Home’s Impact on Cost & Quality: An Annual Update of the Evidence, 2012-2013. . Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative;2014.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Future of Patient Centered Medical Homes and Accountable Care

January 16, 2014