Introduction

The United States has comparatively low voter turnout. One barrier to voting is the registration process. The Pew Research Center estimated that in 2014, 21.4 percent of the voting eligible population in the U.S. was not registered to vote. Unfortunately, the states are not moving consistently toward policies that would increase the registered population. While some states have eased the voter registration process, or moved toward automatic voter registration, others have adopted policies that will likely remove a substantial number of eligible registered voters from the rolls.

There are good reasons to believe voter registration at tax time would be an efficient and effective approach to increasing voter registration. More than 150 million households file their income taxes every year. The slight administrative inconvenience of voter registration is marginal in the context of tax preparation; tax filers are already completing many more complicated forms for a government agency. Associating tax time and voter registration would provide a regular reminder for voters to keep their voter registration up to date. The annual reminder could help counteract voter roll purges, and would complement automatic voter registration systems, especially for those citizens who move frequently or do not drive.

Given the long American tradition of associating taxation with representation, there may well be additional benefits to linking tax filing with voter registration. Taxpaying reminds all filers of the significance of public policy for their daily lives and livelihoods, which might increase interest in political participation. My research has shown that Americans see taxpaying as a civic responsibility, and that when Americans pay for government, they believe they should have a right to help decide how the money is spent.

Moreover, voter registration at tax time has the potential to not only increase the voter pool, but to make the voting population more closely mirror the citizenry as a whole. Low-income Americans are substantially less likely to be registered to vote than higher-income Americans, and are also less likely to vote. In 2016, 74 percent of individuals making more than $50,000 voted, compared to only 52 percent of voters making less than that. Unfortunately, some voter engagement efforts actually widen disparities in participation by mobilizing members of groups already likely to participate rather than underrepresented citizens.

“Voter registration at tax time has the potential to not only increase the voter pool, but to make the voting population more closely mirror the citizenry as a whole.”

Tax time may be an especially effective time to encourage lower-income citizens to register. The tenor of citizens’ interactions with government, both positive and negative, influence their willingness to participate in civic life. Millions of low-income Americans file their tax returns every year. Income tax filing is critical for many working families who rely on the earned income and child tax credits to supplement their incomes. For these households, the experience of tax filing provokes feelings of pride and inclusion, a comparatively positive government interaction. Voter registration at tax time could leverage this positive experience of government to increase civic participation. A reminder to register could also draw voters’ attention to the EITC as a social benefit they receive. Currently, many recipients do not perceive the refundable credit as a government benefit, which may explain why the EITC does not appear to influence beneficiaries’ views on government the way other cash assistance does.

The Filer Voter study tested whether voter registration at tax time could be an effective, low-cost policy mechanism to increase voter registration and turnout, and to improve the representativeness of the voting population. In the spring of 2018, the experiment was conducted via a randomized controlled trial in two major U.S. cities: Cleveland and Dallas.

Experimental Design

Filer Voter was conducted at local Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) centers. VITA tax preparers are IRS-certified volunteers, and VITA sites are coordinated by local or regional nonprofit community organizations. Nationally, VITA programs provide free tax preparation assistance to millions of low- to moderate-income households, generally those making less than $55,000 a year.

The Filer Voter program occurred at seven locations in Cleveland and Dallas from late January to mid-April 2018. Tax filers visiting each of the participating sites were asked to sign a consent form to participate in the study. The experimental pool included 4,353 tax filers.

The project was run as an experiment, following the same basic principles of scientific research that doctors use to test medical treatments. In the case of Filer Voter, the “treatment” was the opportunity to register to vote. VITA site hours were divided into two equal-length shifts every day. Randomly, one of the two shifts was designated a treatment shift, and the other shift was designated a “control” shift. During a treatment shift, taxpayers visiting a site were given the opportunity to register to vote during their intake process. During the control shift, individuals who arrived at the VITA sites were not asked to register to vote. This randomization process helped ensure that we had two groups of participants—a treatment group and a control group—that would be comparable to one another.

To compare the registration rates of the treatment and control groups, we matched our consent form data to data drawn from the official voter registration files maintained by the offices of the Texas and Ohio secretaries of state. We conducted the match to the voter files at two different points in time: once, immediately before the Filer Voter experiment began, and again, after the Filer Voter experiment ended. As a result, we can see who in the treatment and control groups successfully registered to vote, and, for participants in Ohio, who voted in the 2018 primary.1

Participants

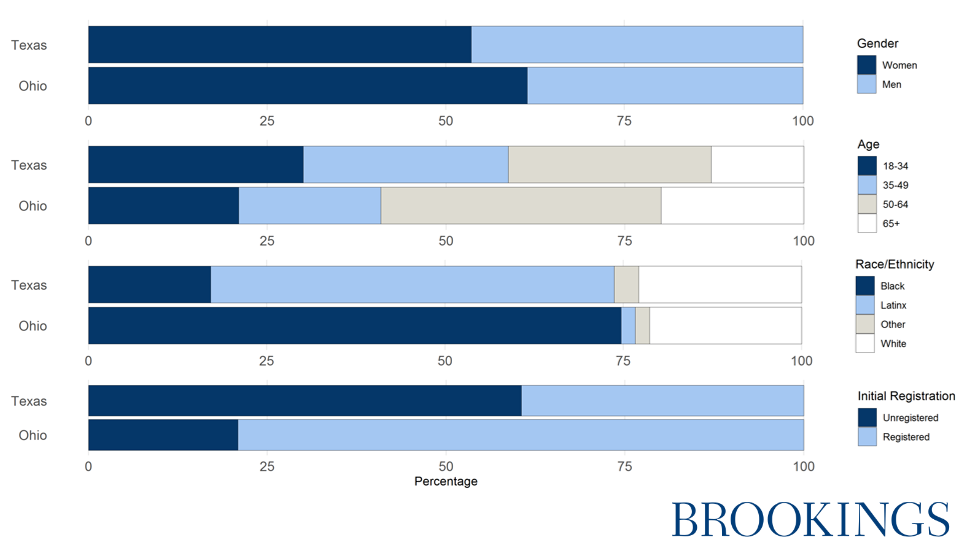

The participants in the two states shared certain demographic characteristics. In both Dallas and Cleveland, women were a larger share of Filer Voter participants than in the general voting-age citizenry; women made up 54 percent of the 2,588 participants in Texas, and 61 percent of the 1,793 participants in Ohio. As expected—given the targeting of VITA services—the participants were also predominantly low-income. In Ohio, the average income for Filer Voter participants was just over $23,000 a year. While Brookings did not have access to individual income data for those who consented to participate in Filer Voter in Texas, we do know that the average income for all VITA clients at those sites was slightly less than $27,000.

Figure 1: Demographics of the Filer Voter participant population in Texas and Ohio

The demographic differences between the participant populations in Dallas and in Cleveland reflect differences in the populations of the two cities. While Ohio Filer Voter participants were mostly (62 percent) African-American, Texas Filer Voter participants were mostly (59 percent) Latino.2 The Texas participant population was heavily Spanish speaking; 45 percent completed their Filer Voter form in Spanish rather than English. Likely because the Texas population had a higher rate of non-citizenship, the percentage of the population that was already registered at the start of Filer Voter were much lower in Texas, as well. The Texas population was also slightly younger; the average age of Ohio participants was 51, compared to 45 in Texas.

Results: Voter Registration

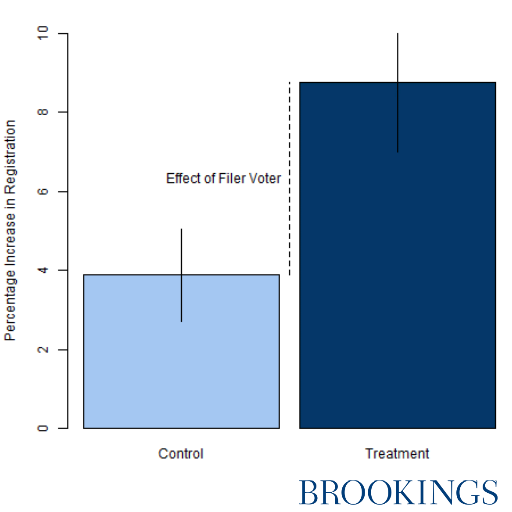

The Filer Voter program significantly increased registration rates among the initially unregistered. In the treatment group, 8.8 percent registered to vote compared to only 3.9 percent of the control group, a 4.9 percentage point increase. That is to say, the Filer Voter treatment more than doubled the likelihood of an unregistered person registering to vote.

Figure 2: Filer Voter program more than doubles likelihood of registering to vote

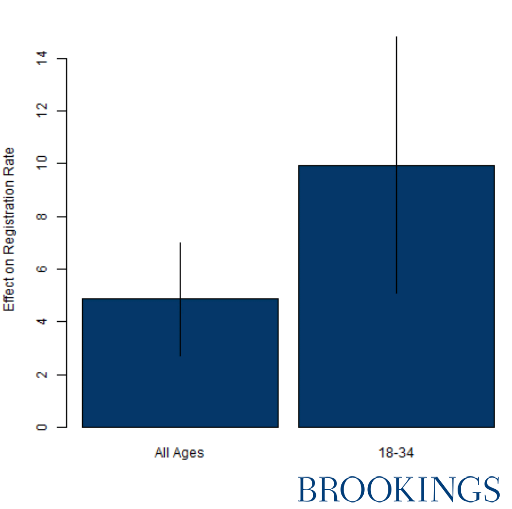

The effects were largest for young people. Among unregistered 18- to 34-year-olds, the program resulted in an 10 percentage point increase in voter registration, as well as a 5.3 percentage point increase in re-registration.3 Those 35 to 49 saw a similar increase in re-registration rates.

Figure 3: Filer Voter program most effective at registering younger participants

Filer Voter’s success in new registrations carried over into increased voter turnout. In the 2018 Ohio primary election, 23 percent of those who newly registered to vote through the Filer Voter program actually voted, a rate slightly higher than the overall turnout for the state, 21 percent. Given that the Ohio VITA client population is low income and predominantly from traditionally underrepresented ethnic minority groups, the turnout rates are especially notable.

Implications for future implementation

Linking voter registration with free tax preparation services is an effective way to increase the civic engagement of lower income citizens. From a practical standpoint, the Filer Voter model offers several advantages as an approach to voter registration. Here, we assess the implications of the experimental results for VITA networks and paid tax preparers; civic engagement and voting organizations; and federal, state, and local policymakers.

For VITA sites and tax preparers

The results of the Filer Voter program suggest that tax preparers could have a very substantial impact on voter registration rates if they offered voter registration to their clients. In addition, offering voter registration services could help nonprofit tax preparers attract volunteers from outside of their traditional volunteer pools.

“We found that there was no measurable change in the rate of tax preparation when voter registration was offered.”

Of course, those interested in offering voter registration may be concerned about slowing their tax preparation processes. As part of the Filer Voter assessment, we calculated whether treatment shifts served fewer clients than control shifts. We found that there was no measurable change in the rate of tax preparation when voter registration was offered.

Moreover, the requirements of the experimental procedure (such as the consent form, the tracking of randomized shifts, and the mailing of documentation to Brookings) were more onerous than a non-experimental voter registration campaign would be. Our data demonstrate that voter registration can occur with minimal effects on the efficiency of tax preparation. (For more information about the implementation process, see the Implementation Appendix.)

For voter registration groups

A primary advantage of the Filer Voter program is its very low cost because it builds on an existing program. For organizations looking to increase voter registration in their communities without the outlay associated with standalone canvassing and tabling efforts, a Filer Voter program would likely be very efficient.

Because the Filer Voter program relied heavily on VITA staff and volunteers, however, a key element of the success of the Filer Voter program was providing training and support for the VITA intake specialists or other volunteers or staff involved in the voter registration procedure. Voter registration organizations interested in partnering with local VITA programs might consider offering volunteers to local VITA sites to offset the work associated with the inclusion of a voter registration drive, or offering small stipends to intake specialists to offset the cost of training and implementation.

For public officials

Filer Voter also has implications for policymakers. As a supplement to automatic voter registration, policymakers should explore policies to incentivize or require tax preparers to offer clients the opportunity to register to vote. Many citizens who might fall through the cracks of an automatic voter registration program, particularly those who do not drive, might be reached via an annual appeal at tax time. States should also explore the feasibility of including the state tax authority among the agencies participating in automatic voter registration by including the option of registering to vote on the state income tax form.

Such legislation would be in keeping with the spirit of the National Voting Registration Act of 1993, colloquially known as the “Motor Voter” Act, which requires state governments to help eligible citizens to register to vote when they visit the department of motor vehicles or any state agency providing public assistance. Income tax filing is unusual in that it is a public function performed by private agencies, but like driver’s license renewal, it is a regular touch point citizens have with their government, and should be harnessed to increase voter registration rates.

The impact of site selection: Texas and Ohio

A vital question for any field experiment is its external validity—that is, the likelihood that the results achieved will be replicable in other circumstances. We believe that the context of the 2018 Filer Voter experiment was an especially difficult one for the project, meaning that results may well be even stronger in other times and locations.

In choosing locations for the 2018 Filer Voter experiment, we sought out VITA networks with especially large tax filing programs, and we moved forward with two of the largest city-level networks that were interested in participating: Foundation Communities in Dallas, and Enterprise Community Partners in Ohio. Going into the project, we were aware that Texas was likely to be the more difficult test of the Filer Voter model.

First, the client population in Dallas was likely to include a larger percentage of noncitizens, meaning fewer clients would be eligible to register to vote. By contrast, the population of tax filers in Cleveland was overwhelmingly native-born and therefore eligible to register.4

In addition, the experiment took place during a period of heightened immigration enforcement. Concerns about potential action by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) likely reduced attendance at VITA sites. Many households have members with different citizenship and immigration statuses; the fear of ICE activity may have had a chilling effect on the willingness to register to vote for citizens with undocumented family members.

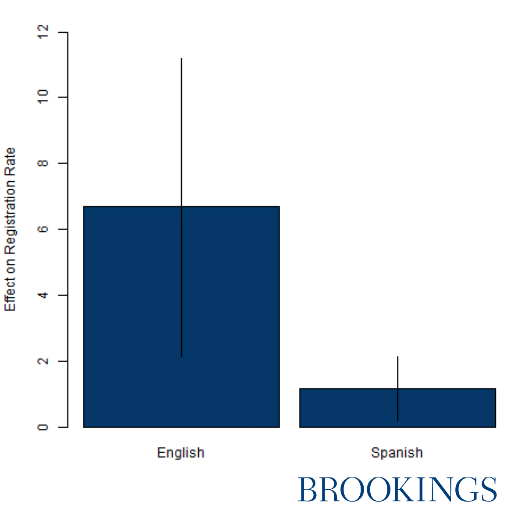

The results provide evidence for at least some of these concerns. While the Filer Voter program successfully raised voter registration rates for both English and Spanish speakers, the effects were substantially larger for English speakers.

Figure 4: Smaller registration effects for Spanish speakers

Compounding the challenge in Texas is the state’s voter registration rules. The state requires anyone collecting voter registration forms to become a volunteer deputy registrar—a post available only to people qualified to vote in Texas—that requires taking a special training course from the county and a substantial paperwork burden associated with each voter registration form collected. Deputy voter registrars must be separately deputized on a county-by-county basis. In addition, any voter registration forms collected must be hand delivered by the deputy voter registrar to the county within five days. Failure to comply with these requirements is a misdemeanor offense. In contrast, Ohio, like most states, lets volunteers collect voter registration forms without special training and certification, and volunteers generally have 10 days to mail forms to the county. According to the Brennan Center, Texas is among the states with the most “unreasonable and onerous” restrictions on voter registration drives.

“That the project was successful in such difficult circumstances suggests that it may show even stronger results in states with less restrictive voter registration drive regulations.”

That the project was successful in such difficult circumstances suggests that it may show even stronger results in states with less restrictive voter registration drive regulations. Those interested in implementing a Filer Voter program in states like Texas—with a large noncitizen population and very restrictive voting laws—should feel confident that the program has been tested in such a rigorous environment.

Conclusion

The Filer Voter program increased voter registration and turnout. The program doubled the likelihood that a person not registered to vote would become registered. Put another way, fully half of the people newly registered to vote via the Filer Voter program would not otherwise have registered. The program largely avoids the costs associated with recruiting and training new volunteers to implement a voter registration program, and did not slow the tax preparation process at the sites where voter registration was offered. The results offer a roadmap for nonprofit organizations, for-profit preparers, and state officials who wish to harness the tax filing process to substantially increase civic participation in their communities.

Appendix

This appendix provides additional details for those interested in implementing a voter registration program at VITA sites (“Implementation”) and those seeking more information about the statistical methods used to assess the data (“Technical Specifications”).

Implementation

When a client enters a VITA site, they are typically greeted by an intake volunteer who provides the client with the IRS-mandated intake form, and often some additional materials (such as a survey or information about additional benefits the site offers). The client then sits in a waiting area while completing these forms, and then returns to the intake table to have their forms checked and to allow the intake volunteer to ensure the client has all their required tax documentation (such as their W2s). Once the intake process is complete, the tax filer returns to the waiting area until a tax preparer is available to assist them.

At the Ohio Filer Voter sites, the intake materials included the IRS form, the experimental consent form, and the voter registration form (during treatment shifts), and a short survey. Including the experimental forms at intake allowed participants to complete their forms on their own time. Intake workers simply had to collect the forms when the client returned to have their tax documentation checked, and ensure they were submitted to county authorities in the locally authorized manner.

In Texas, local law required a different procedure. At each site, after receiving their paperwork for the VITA intake volunteer, tax filers were directed to a deputy voter registrar who completed the voter registration process.

We recommend the intake process and attendant waiting period as a good time to conduct voter registration drives. However, tax preparers should feel free to modify our procedures to fit with their own processes and with local voter registration rules.

Technical Specifications

VITA clients who completed a consent form, resided in the state, and were at least 18 years old at the time of the study were eligible to be included in the Filer Voter evaluation. Of the participants, 175 were removed from the analysis due to an error in treatment assignment. Another 34 participants were removed because they attended more than one site shift (for instance, when clients did not have their required tax paperwork and had to come back). Lastly, 141 were removed because there was an error in the implementation of treatment and control shifts (for instance, when a storm in Texas prevented volunteers from arriving at their designated sites).

The populations in the treatment and control group appear balanced across measurable characteristics, suggesting the shift randomization was successful.

| Control | Treatment | |

| Male (%) | 44 | 42 |

| Age (average) | 47 | 48 |

| Unregistered (%) | 46 | 43 |

| White (%) | 13 | 14 |

| Black (%) | 29 | 31 |

| Latino (%) | 17 | 16 |

| Spanish Language (%) | 28 | 25 |

Results for all registration and turnout models are based on logistic regressions with controls for age, gender, language, site, state, day of the week, and the number of days from the tax-filing deadline, and errors are clustered at the shift level. Results for initially unregistered participants also include a control for whether the participant matched to the voter file at the start of the test. In all graphs, error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Acknowledgements

We deeply thank the following organizations and individuals in Dallas and in Cleveland for their participation in the Filer Voter project. In Dallas, Ronnie Daniels, Amanda Arizola, and Amber Jefferson of Foundation Communities, as well as the site coordinators and intake specialists at West Dallas Multipurpose Center, North Dallas Share Ministries, and First Community Church; Lydia Bean and Candace Rembert of Faith in Texas, along with their hundreds of volunteers; and our Deputy Voter Registrars, Alice Holmes and Mary Wise. In Ohio, Maggie Campbell of Refund Ohio, as well as the site coordinators and intake specialists at the Burten Bell Carr, CHN Housing Partners, Famicos, and Lin Omni VITA sites.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

Brookings gratefully acknowledges the support provided to the Governance Studies program by the New Venture Fund’s Research Collaborative Fund project. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

-

Footnotes

- Turnout rates in Texas were not calculated because the registration deadline for the March 6 primary was too early to fit with the tax season timeline.

- Racial statistics for Texas were less complete than Ohio; these percentages were calculated after filtering respondents of Unknown or Missing race.

- Re-registration refers to registration by those already registered to vote but who need to update their voter information, for instance to reflect a new address or a change of name.

- Another state-level difference affecting voter registration eligibility is felon disenfranchisement. Texas has a more stringent policy than Ohio regarding the re-enfranchisement of the formerly incarcerated. This, to a lesser degree than overall citizenship rates, reduces the percentage of the Texas population that is voting eligible.