For most people Labor Day provides a temporary respite from work in the form of a three-day weekend. But what would happen if three-day weekends became the norm—if work declined in a more permanent way as machines replaced humans in the form of self-driving cars, drones, robots on the factory floor and in the home, computer-based scheduling in the office, and automated check-out systems in retail stores?

Maybe the fears are justified, this time round?

Economists have long dismissed such scenarios, arguing that technology creates new jobs as the old ones disappear and that human wants are never satisfied. But even former Treasury Secretary, Lawrence Summers, has begun to question the conventional wisdom, and in a recent article in the Atlantic, Derek Thompson argues that fears about technology destroying jobs and leading to a new normal may be all too real.

Thompson sees three reasons to be worried: the fact that less and less of our national income ends up in the pockets of the work force, the falling share of prime-age men who are working, and credible projections that machines could replace people in half of all U.S. jobs in the next several decades. Thompson challenges us to think about a society in which work is far from universal and what might take its place. He suggests a number of scenarios: more leisure, more artisanal and personally satisfying kinds of work, more contingent work (think of the self-employed, part-time Uber driver). Or perhaps a government-sponsored marketplace or digital WPA that links workers to specific tasks.

What’s so great about work anyway?

Why is work routinely heralded as such a valuable thing? If productivity advances enough to provide a decent income for most people, replacing work with other activities might make a lot of sense. But revaluing work would require a new mindset in which industriousness, economic growth, and ever-higher levels of consumption are no longer viewed as the paramount goals of an advanced economy.

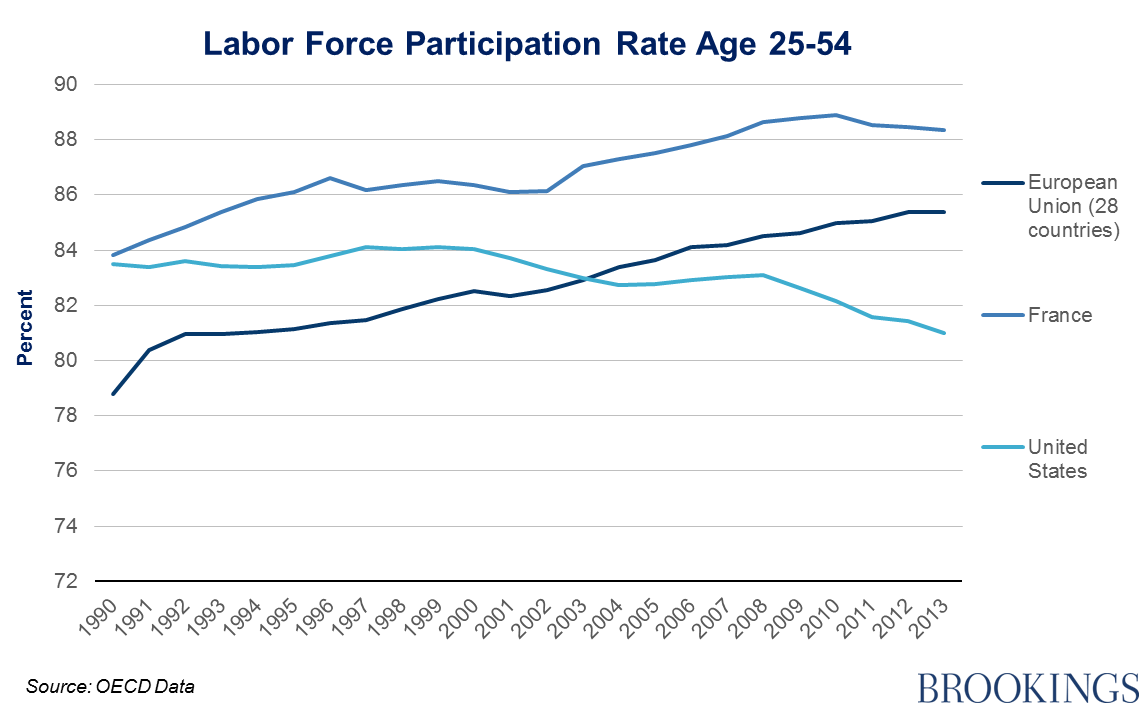

Right now, the United States is an outlier where work is concerned. Annual hours worked per worker have fallen sharply in Europe since 1950 but only modestly in the U.S. At the same time, the labor force participation of prime-age adults, especially men, has collapsed with the U.S. now falling below most other industrialized economies, even the allegedly laid-back French.

It is too soon to say whether this is a cyclical or structural phenomenon or whether it is a big problem (the conventional wisdom) or an unrecognized opportunity to find a better balance between work and other activities. The satisfactions of work are, of course, very unevenly distributed. While the best-educated may enjoy their work, those in lower-level jobs would almost surely welcome more time off.

Providing them that opportunity would require a recognition that an affluent society can afford to provide more support to those whose skills do not enable them to earn a decent living in a high-tech society. A step in that direction would be to offer earlier Social Security benefits to those in low-wage jobs while extending the retirement age for high-wage workers.

All of this may seem a long way in the distance. But this Labor Day we might spend some of our extra leisure time considering what life would be like with a lot more.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The end of laboring days?

September 8, 2015