For three days last week, Pakistan was riveted by a surprise legal crisis over an extension in the term of its Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa. It was a last-minute showdown — just before General Bajwa’s term was set to expire on November 28 — between the federal government, which had ordered the extension, and the Supreme Court, which on November 26 took notice of a petition challenging it and suspended the extension.

This case was unprecedented — no such hearing over an extension for an army chief has ever been held in Pakistan, despite a history of army chiefs’ tenures being extended. The case also has wider, significant implications about the state of civil-military-judiciary relations in Pakistan.

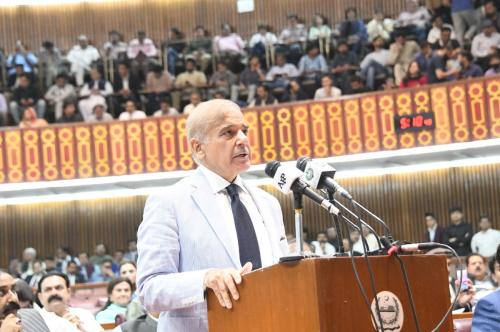

Pakistan’s most powerful man

Many consider Pakistan’s chief of army staff to be the most powerful man in the country. In August, more than three months before General Bajwa’s three-year term was set to end, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s government — citing an emergency in the “regional security situation” — issued him a three-year extension beyond November. The regional security issues at play were India’s revocation of Kashmir’s autonomy and Pakistan’s ongoing help in the U.S.-Afghan peace process. But many argued at the time that by granting Bajwa an extension, Khan was ensuring smooth sailing for his government for another three years — given the ways in which the army, under Bajwa, had paved, or perhaps primed, the path for Khan to become prime minister last year.

The chief justice and Supreme Court took the federal government and its attorney general to task last week, pushing the decision down to the wire: the day the army chief was set to retire. The court argued that the government had botched the bureaucratic process for Bajwa’s extension (alternately referring to it also as his reappointment, or the limiting of retirement), but it also emerged during the proceedings that there was no legal basis — not in the constitution, nor in the army rules — for this extension, and certainly nothing that specified that the duration needed to be three years. It appeared the government had simply followed previous practice: Army chiefs either granted themselves extensions when they were in power, or civilian leaders did so. Most recently this occurred in 2010, when President Zardari extended the term of then-army chief General Ashfaq Kayani.

The court’s reaction

Chief Justice Asif Saeed Khosa (himself set to retire this month) called on the government to “step back and assess what it is doing” and to “not do something like this with a high-ranking officer,” also pointing out that the “regional security situation” justification for the extension was “quite vague.” He even gently questioned its validity: “[I]f at all there is any regional security threat then it is the gallant armed forces as an institution that are to meet the said threat and an individual’s role in that regard may be minimal.” That is about as far as any chief justice has ever gone in Pakistan in pushing back against the army or its chief. But during the court proceedings, Justice Khosa mostly ended up castigating the law ministry for its “errors” that he said were causing “disrespect” to the army chief.

Analysts were beside themselves trying to predict what would happen on November 28, warning of the instability that would follow a potential court decision that struck down the army chief’s extension altogether. The power an extension grants to the army chief, and the blow that would follow from it being revoked, was not lost on anyone. In the end, the court saved face all around: It gave the army chief a six-month extension (the legal basis of which, it should be pointed out, is in itself unclear), and directed the federal government to have parliament legislate on such extensions and their duration.

There is a real question as to whether parliament will get to legislation that essentially gives legal justification for past practice — that is, long, multi-year extensions for army chiefs — or whether it seriously debates it. Khan has a majority in the lower house, but the opposition has control of the senate, and the polarization between Khan and the opposition parties has thus far all but stalled the legislative process.

There is also the question of what prompted the chief justice to take notice of the petition challenging the army chief’s extension at the last minute (intriguingly, after the petitioner tried to withdraw it). The last extension to be granted, General Kayani’s, had also been challenged in the Islamabad High Court in 2010, but that petition was struck down. Some speculated that rival officers to General Bajwa prompted this case; others considered the recent back-and-forth between Khan and the judiciary over the cases of former leaders Nawaz Sharif and General Pervez Musharraf to have provoked it. The simpler narrative is that it was the bureaucratic errors and lack of legal basis for the extension that made the chief justice, eager to make a mark in the month before his retirement, take notice.

Do Pakistan’s civilian institutions stand a chance?

Whatever the prompt, the whole affair — and its clash of egos and a tug-of-war over power — reveals two things: In Pakistan, Khan’s government is beholden to the army (at least to its current chief); and opposition parties are also unwilling, or unable, to take it on.

Nawaz Sharif’s party is the only one which has tried to take on the military in recent years; in 2016, it tried to assert some semblance of civilian supremacy over security policy, and many attribute Sharif’s downfall (ostensibly over corruption) to that butting of heads. With Sharif currently in England for medical treatment, his party seems to have been silenced into submissiveness vis-à-vis the army. The federal government also showed its weakness relative to the judiciary: It was left bumbling and panicked by the last-minute hearing, unable to successfully defend itself, or its constitutional prerogative to appoint (and presumably reappoint) the army chief, in court while the justices berated it.

Second, there might be a new front opening between the judiciary and the military. In the past, the judiciary has mostly unconditionally supported the military at the expense of civilian governments, rubber-stamping military coups via the “doctrine of necessity” and disqualifying prime ministers, including Nawaz Sharif. (The prominent exception of course was the clash between Musharraf and the judiciary, prompted by Musharraf’s sacking of the chief justice in 2007, that ultimately led to his own downfall.)

This new judiciary-military tension — and it may not last — at the very least has forced the country to think about a practice that it took for granted that effectively strengthened the military at the expense of civilian institutions. In parliament, this practice of extending the army chief’s tenure may get codified, or struck down, or qualified, and the direction that takes will be significant. But beyond that, the weakness of Pakistan’s civilian government vis-à-vis both the army and the judiciary is clear: The judiciary has, at least in this case, assumed the role and the power (whether legally or not) to force Pakistan’s politicians to fully define its institutions. This whole episode will figure in the saga of what kind of democracy Pakistan will be, and how its politicians will shape its institutions — whether to the strength of its civilian government, or to its detriment.

Commentary

The curious case of the Pakistani army chief’s extension

December 4, 2019