This working paper is part of a multi-year Brookings project—”The One Percent Problem: Muslims in the West and the Rise of the New Populists.” Other papers in the series are available here.

Contents:

- Newcomers in a “guiding nation”

- The rise of the radical right

- Missionaries against Islam and mass immigration

- The “nature” of Islam

- “The biggest problem in the Netherlands”

- Framing Islamization

- Political and societal implications

When Geert Wilders, founder and front man of the Party for Freedom (PVV), explained his “Plan for the Netherlands” in the build-up to the Dutch general election of 2017, he declared that “the biggest problem in this country is Islamization.” This process, Wilders claimed, constitutes an “existential threat” to “our identity, our freedom. Who we are. Everything.”1 For close observers of Dutch politics, similar statements, made by the leader of the then third-largest party of the country (second-largest after the elections), were stale—over the preceding decade they had grown accustomed to Wilders’ Islam-alarmist messages. His claims may sound rather radical, however, to foreign ears. After all, most of Wilders’ political friends in European Parliament do not denounce Islam as directly or explicitly;2 nor is the issue as salient for them as it is for PVV leader. Besides, didn’t Wilders come from and operate in the Netherlands, a country that has long been prided for its cultural openness and religious tolerance?

This paper aims to contribute toward a better understanding of the ways in which immigration in general, and Islam in particular, are politicized in the Netherlands—a history in which Wilders plays a key role, though he is not the only protagonist. I will do so by focusing, first, on the societal background against which these issues surfaced on the political agenda during the past decades. I will then analyze how the issues of immigration and Islam are depicted by Wilders’ PVV and how these representations evolved over time. The final section will situate this politicization in the contemporary Dutch political landscape and discuss its societal implications.

Newcomers in a “guiding natioN”

Ever since the “Dutch Golden age”—spanning roughly the seventeenth century—the Netherlands has been an attractive place for migrants. During this period, many sought shelter in the relatively tolerant and prosperous republic for politico religious or economic reasons. In numerical terms, this period of “mass-migration” was only matched after the Second World War, when successive waves of immigration significantly increased the size of the Dutch population.3 These waves of immigration sprang from three main sources: the post-colonial situation in Indonesia, Suriname and the Antilles; “guest workers,” recruited during the 1960s, notably from Turkey and Morocco, who would become permanent residents and—together with their families—represent 4.7 percent of the Dutch population today;4 and, asylum seekers, whose numbers peaked in the early 1990s (due to the war in Yugoslavia) and more recently amid the migrant crisis sparked by the Syrian Civil War.5

Although there are many other (smaller) migrant groups in the Netherlands,6 public debate around immigration and multiculturalism tends to be concentrated on non-Western migrants, especially those of Turkish and Moroccan origin—due in part to the fact that these groups largely account for the growth of Islam within an increasingly secularized society. About six percent of the current population in the Netherlands is estimated to be Muslim,7 compared to less than one percent in the early 1970s.8 It was during precisely these four decades that large parts of the Dutch population lost their faith.9 From a relatively religious society that was segregated along different socio-cultural pillars—mainly Catholic, Protestant and socialist—the Netherlands became one of the most secularized countries in Europe, characterized by progressive sexual morality, which allowed for the world’s first legalization of same-sex marriage in 2001. Similar progressive successes contributed to a Dutch self-image as a “guiding nation” (gidsland).

The ethical views that thus gained popularity during the second half of the 20th century, notably concerning female emancipation and gay rights, pushed even conservative politicians to embrace and incorporate progressive values. As will be discussed below, this development is critical to understanding the peculiar ways in which Islam is politicized by Dutch radical right politicians.10

The rise of the radical right

In contrast to other European countries—such as Austria, Denmark, France, Norway, and Switzerland—where political parties advocating anti-immigration policies became electorally successful from the 1980s onward, challenges to migration policies were relatively slow in coming to the Netherlands.11 Prior to the September 11 attacks, such proposals were generally associated with the extreme right. In the political arena, and public debate more broadly, anti-immigration positions were embodied by Hans Janmaat, the first Dutch politician to openly call for the abolition of multiculturalism. Due to Janmaat’s relative dearth of charisma and effective marginalization by journalists and establishment parties, his Centre Party (later Centre Democrats), never obtained more than 2.6 percent of the vote share in the 1980s and 90s.12 At this time, Dutch politics were characterized by an elite consensus on immigration. Based on a “gentlemen’s agreement,” the leaders of the main political parties generally refrained from using the issue in electoral campaigns at the expense of migrants.13

Within the ranks of the main political parties, however, there was one important exception: Frits Bolkesteijn, the leader of the liberal-conservative governmental party VVD from 1990 to 1998, who would become the most prominent figure of a conservative current that increasingly altered the Dutch intellectual and political landscape.14 In September 1991, in the aftermath of the Rushdie Affair and the first Islamic scarf controversy in France, (and before Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations (1993)), Bolkesteijn launched a debate in the Netherlands about the integration of Muslim immigrants “from Morocco and from Turkey,” by contrasting cultural relativism and Islamic practices with the universal superiority of three liberal principles: separation of church and state, freedom of expression, and non-discrimination, notably vis-à-vis women. While emphasizing that liberalism’s fundamental values cannot be compromised, Bolkesteijn predicted that “[o]ur relations with these new immigrants from a different culture will feature very high on the list of political priorities in the years to come.”15

Before the issue would explode onto the Dutch political scene, however, the VVD leader moved to Brussels to become a European Commissioner. Within his party, Bolkesteijn’s influence had dwindled when more progressive politicians came to the fore, such as his successor Hans Dijkstal. Meanwhile, opinion polls—from the early 1980s onwards—indicated that many citizens in the Netherlands were critical of the immigration of newcomers, and even supported voluntary remigration. Similarly, the Dutch post-electoral surveys (from 1994 onward) consistently showed that a majority of the population preferred that immigrants assimilate (aanpassen) rather than retain their own culture.16 These surveys indicated electoral potential for political entrepreneurs articulating positions critical of immigration and integration.

In the build-up to the general election of 2002, Pim Fortuyn would become the first Dutch politician to make these issues a central element of his electoral agenda without being marginalized as a racist and extremist. The openly homosexual former sociology professor, and author of Against the Islamization of our Culture (1997),17 saw his controversial opinions gain credibility after the 9/11 attacks, when the integration of Muslims became a widely discussed topic in the Netherlands. On May 6, 2002, however, Fortuyn was assassinated by an environmental activist nine days before the Dutch general election. Posthumously, his Pim Fortuyn List (LPF) obtained 17 percent of the vote—the highest ever result for a first-time party. Nevertheless, the fatherless LPF’s participation in a coalition government soon led to internal struggles: the coalition lasted for 87 days and the party founded by Fortuyn only won 5.7 percent of the vote in the subsequent election. In 2006, when the next parliamentary elections were held in the Netherlands, the LPF lost all seats.18 By then, Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom had emerged as its successor.

Missionaries against Islam and mass immigration

The Dutch Party for Freedom is an exceptional party not only in matters related to Islam, as will be discussed in more detail below, but also in terms of organizational structure. To my knowledge, the PVV is the only political party in the world that counts just one official member, Geert Wilders. Accordingly, the selection of candidates, decisions about the party’s planning, political program, and policies all depend upon the same person: the party’s founder, supported by a couple of loyal adjutants.19

This organizational structure was partly developed to avoid chaotic “LPF-like situations.” Yet it also relates to the security measures with which Wilders has been confronted since November 2004. In that period, two months after he left the VVD to start his own political adventure (initially called Group Wilders), filmmaker Theo van Gogh was murdered by the Dutch-Moroccan Mohammed Bouyeri—a crime allegedly triggered by the broadcasting of Van Gogh’s and Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s short movie Submission earlier that year, in which they critically address the subordinate position of Muslim women. Soon after the murder, which again stirred debate about the integration of Muslims in Dutch society, it turned out that Wilders also figured on the “death list” of Bouyeri’s sympathizers. Ever since, Wilders sleeps in safe houses and lives under strict round-the-clock police protection. Although this dramatic change in Wilders’ personal life had a positive impact on his publicity, it made building up a party more complicated. As Martin Bosma, who joined Wilders in 2004 and is often described as the party’s ideologist noted: “We have to operate like a semi-underground resistance organization.”20

This delicate safety situation in which Wilders and his colleagues found themselves since the beginning of their party undoubtedly contributed to a distinctive self-image. Rather than being solely office seekers, they consider themselves conviction politicians, for whom the fight against Islam and mass immigration are as important as electoral success—if not more so. In Bosma’s terms:

“Of course, we, like all other parties, also hope to do well in the elections. But our task is also another one, namely to tell the story of Islam and mass immigration in order to counterbalance the pink fantasies that the elites above us depict. Opening up the discussion is at least as important as the number of [Parliamentary] seats that we get. We are not just politicians, we are also a bit of missionaries.”21

During a March 2014 interview with the Dutch news website NU.nl, Wilders even claimed that he entered politics for just one reason: “fighting Islam.”22 Behind the scenes, Wilders’ former personal assistant and former PVV MP, Johan Driessen, often heard similar stories. “Islam is actually the only thing Geert is interested in,” Driessen told me, “the rest is just irrelevant to him.”23 The relative importance of Islam-related issues was confirmed in my recent analysis of Wilders’ Tweets. Between 2011, when the PVV leader started to use the medium more frequently (in a Trumpian fashion avant la lettre) until January 2018, 22.7 percent of all the issues he tweeted about were negative statements about Islam—surpassing any other issue.24

The “nature” of Islam

The first significant aspect of the PVV’s politicization of Islam relates to the alleged nature of the religion. In 1991, Wilders’ political mentor, Frits Bolkesteijn, stated that “Islam is not only a religion, it is a way of life. In this, its vision goes counter to the liberal separation of church and state.”25 Wilders, who was likened by Bolkesteijn to Goethe’s sorcerer’s apprentice,26 went several steps further over the course of his political career, defining Islam in increasingly ideological terms, while claiming that a moderate version of Islam does not exist. Initially, these arguments were reserved for political Islam. For instance, in March 2004, when still an MP for the VVD, Wilders (together with Ayaan Hirsi Ali) denounced political Islam as “a nihilist, anti-Semitic, violent religious ideology that in terms of human contempt equals national-socialism.”27 Similarly, two years later, in the PVV’s intellectual manifesto, “A New Realistic Vision,” Wilders and his colleagues warned about the “confrontation with the violent ideology of the political Islam,”28 but did not invoke negativity toward Islam tout court. Inspired by works such as Oriana Fallaci’s The Force of Reason (2004) and Bat Ye’or’s Eurabia (2005), this confrontation with political Islam became more and more a confrontation with Islam itself—the latest episode in an age-old struggle between the forces of good and evil. Accordingly, in the PVV’s party manifestos after the 2006 elections, Islam is not described as a religion but as “a totalitarian political ideology with some religious tinges” which “prescribes to its supporters a perpetual war until the moment that the whole world is Islamic.”29

Illustratively, when the PVV supported a right-wing minority coalition after the 2010 general elections (the so-called gedoogsteun that lasted until 2012), discord over the nature of Islam led to an “agree to disagree” statement by the three concerned parties. Whereas the VVD and the Christian Democratic party considered Islam to be a religion, Wilders insisted that Islam should be defined as a “political ideology,” thus highlighting the importance of this distinction in the eyes of the PVV leader.30

“The biggest problem in the Netherlands”

Wilders’ firm stance on the nature of Islam is related to a second aspect of his party’s politicization of the issue—the increasingly overarching significance of Islam within the PVV’s discourse. In its first party manifesto, published in 2006, the issue was only mentioned briefly and in passing. Subsumed under the label “Stop immigration / Integration”(Immigratiestop / integratie), it figured in one out of nine thematic issues in the manifesto, with tax cuts, crime, and education occupying the first three places respectively. The following year, amid the annual General Political Debate on the Budget Memorandum, Wilders stated for the first time that “Islam is the biggest problem in the Netherlands,”31 a claim that he would repeat in the build-up to the general election of 2017. Meanwhile, from being principally mentioned in relation to immigration and integration in the early days of the PVV, the issue of “Islamization” became increasingly articulated in an all-embracing way. According to the 2010 party manifesto, it would affect no less than all facets of society:

“Anybody who thinks that Islamization is a matter of just one issue cannot count. Mass immigration has enormous consequences for all facets of our society. It is a disaster in economic terms, it affects the quality of our education, increases insecurity on the streets, leads to an exodus from our cities, extrudes Jews and gays and rinses women’s emancipation through the toilet. To just highlight one sector: even health care is Islamizing rapidly. Muslim women who refuse treatment by male doctors, who do not want to be washed by male nurses, Islamic elderly who claim halal food from the cooks in their nursing home, homecare workers who have to bring an interpreter with them because the patient only speaks Turkish or Arabic. And who, do you think, pays that interpreter? And why is that interpreter necessary anyway?”32

The overarching presence of “Islamization” within the PVV’s political discourse does not mean that there is no prioritization of its alleged implications. Quite the contrary; for Wilders, some aspects of the multi-faceted threat of Islamization are more important than others, as I will demonstrate.

Framing Islamization

When looking at the excerpt above from the PVV’s 2010 manifesto, it is somewhat remarkable to note that negative implications of Islamization are first framed in economic terms. To be sure, by contrasting “idle Muslim migrants” on the one hand to “hardworking” natives on the other, Wilders has stated more than once that the Dutch welfare state has become “a magnet for fortune seekers from Islamic countries,” leading to a situation in which “Henk and Ingrid” (the PVV’s equivalent of Average Joe) would “pay for Ali and Fatima.”33 Similar statements are interesting from an electoral point of view—that is, to provide hierarchies of worth and status to (potential) voters and broaden the party’s constituency. Yet, for Geert Wilders, Islamization of the Netherlands constitutes more than a mere economic affront. In fact, the PVV leader has repeatedly qualified the issue as nothing less than an existential problem. In the lead-up to the 2017 general election, he declared that “[t]he Netherlands won’t be the Netherlands anymore in a couple of years. We are losing our country and that’s not measurable with money.”34 Put differently, for Wilders, Islamization greatest threat is not economic but cultural. The predominance of cultural over economic concerns has characterized the top rung of the PVV ever since the party was founded. As Auke Zijlstra, a member of the European Parliament for the PVV, recalled when describing the selection process for parliamentary candidates ahead of the PVV’s first general election in 2006:

“I think that everyone who talked more about Dutch culture than about prosperity left a positive impression in the eyes of those who were organizing things. Martin Bosma, for instance, was there already, Geert himself was there too. I just had a nostalgic story about my youth and how that was lost, that part of the Netherlands, how it had all disappeared, and I think that is what caught on. People who talked about things like ‘it is a shame with those high taxes and medical expenses!’ Yes, no doubt, absolutely, it’s a disgrace. Whatever.”35

Importantly, both Zijlstra’s “nostalgic story” and Wilders’ statement that “we are losing our country” have demographic roots—that is, they have to be understood in relation to the increasing share of Muslim migrants within the Dutch population, and the fear that the former might one day become the numerical majority. In this light, the excerpt from the PVV’s 2010 manifesto illustrated an equivalence between “Islamization” and “mass immigration.” Over time, the PVV leader would communicate an increasingly alarmist messages, echoing Renaud Camus’ claims about the “great replacement.”36 In April 2017, for instance, Wilders warned that “[i]f we don’t do something right now, the Netherlands will soon be an Islamic country,”37 adding five months later that “[o]ur population will be replaced if we don’t act quickly. Stop the Islamization of the Netherlands and the West!”38

Similar statements are often justified through culturalist oppositions between “barbaric” Islam on the one hand and “our” Judeo-Christian and humanistic culture on the other. From the party’s first manifesto to Wilders’ “plan for the Netherlands,” published in the run-up to the last general election, the PVV has frequently claimed that “[o]ur values are not Islamic, but based on the Jewish, Christian, and humanistic civilization.”39 In the footsteps of Pim Fortuyn, who famously remarked that he didn’t “feel like going through the emancipation of women and homosexuals all over again,”40 these stances are explicitly connected to progressive values, such as gender equality and gay rights. By defending the latter, Wilders is not only capable of depicting Islamic culture as intolerant, sexist, and homophobic; it simultaneously allows him to claim the superiority of a Dutch national identity that is increasingly intertwined with secularism. Paradoxically, the PVV leader thus presents values that were historically associated with anti-religious and anti-Christian attitudes as achievements of Dutch Judeo-Christian culture.41

This embrace of progressive values, which has become almost a requirement for the electoral success of conservative parties in the highly secularized Dutch context, makes the PVV a rather peculiar case in comparison to its political allies abroad. One thinks of Matteo Salvini’s pro-family stances or Marine Le Pen who publicly denounces gay marriage and the possibility of adoption for homosexual couples.42 Indeed, to use the words of political historian Koen Vossen, it is hard to imagine any of the PVV’s political partners “offering a resolution in parliament to allow gay soldiers to wear their military outfit in a gay parade.”43 Like Wilders, these parties are also opposed to immigration, while appealing strongly to national identity, yet they don’t share quite the same values. “Their only point in common,” as Olivier Roy recently noted, “remains their denunciation of Islam, which goes beyond all their differences on what should be a society without Islam.”44

Wilders invokes one issue more often than national identity when articulating his anti-Islam stances. My analysis of the PVV leader’s Twitter messages indicates that almost 40 percent of all the tweets in which he combines at least two issues contain a link between Islam and security.45 One thinks of Wilders’ claim that “Less Islam = less terror,”46 or that “Islam doesn’t belong to us. It brings violence and danger everywhere.”47 This frequent association reflects both the context of terrorist attacks by Muslim extremists in recent years and the fact that Wilders himself lives under the threat of attack. Although the PVV front-man continues to receive death threats since September 2003,48 he has grown “even more aware what can happen if you criticize Islam,” as a PVV volunteer, who knows Wilders personally, explained. According to this volunteer, Wilders is “the living proof that Islam does indeed take away freedom. If you don’t agree with them, they will take away your freedom, or even your life.”49 At the same time, the issues the volunteer associates with Islam are not the sole responsibility of Muslim migrants. In his view, they also relate to “politics.” Not only “have the guest workers been brought here by politicians in the past,” he argues, but even today, political parties other than the PVV would ignore the urgency of the situation, as they “don’t have any anti-Islam standpoints, at all.”

This brings us to the final important aspect of the PVV’s politicization of Islam: the anti-establishment factor. As Martin Bosma described, the objective of the PVV’s “missionary” work is to “counterbalance the pink fantasies that the elites above us depict.”50 In line with Fortuyn, who famously denounced “the left-wing church” (de linkse kerk), this critique is mainly against “leftist” elites, who have taken over “many crucial positions in society”51 since the late 1960s and have brainwashed the Dutch population with cultural relativism and egalitarianism. Due to their influence in society, they are not only “responsible for the multicultural nightmare we are subjected to,” as the PVV’s 2010 party manifesto reads, but further, “their alliance with Islam also means that there are physical threats. The fate of Pim Fortuyn and Theo van Gogh is a warning and a reminder.”52 Importantly, these articulations of alarmism around Islam and anti-establishment positions go beyond national borders, rather, they also concern supranational organizations, notably the European Union, “the multicultural super state which has Brussels as its capital—the empire that wants to impose even more Islam on us in order to take away every memory of an independent and recognizable Netherlands.”53 Due to this “club in Brussels,” as Wilders and his colleagues quip, “Europe is rapidly becoming Eurabia.”54

Political and societal implications

Due to the particular importance the PVV attributes to Islam, Wilders’ party constitutes a rather exceptional phenomenon—not only compared to his political allies in the European Parliament, but also within the Dutch political landscape and even the broader spectrum of nationalist conservative parties in the Netherlands. The new right-wing anti-establishment party, FVD (Forum for Democracy), offers an important contrast. While the FVD obtained 1.8 percent of the votes in the general election of 2017, it grew to become the largest party in the 2019 Dutch provincial elections, with 14.5 percent of the popular vote. The party’s success, among a wide range of social groups, including the better educated and financially well-off segments of Dutch society,55 is partly due to the party’s positioning as a more moderate alternative to Geert Wilders’ PVV. “They have something raw,” as the FVD’s leader Thierry Baudet put it, “we are more refined.”56 In the Dutch political debate, these differences are particularly related to the issue of Islam, on which Wilders made increasingly provocative statements. In September 2009, for instance, the PVV leader proposed a tax of 1,000 euros on headscarves wearers, or has he dubbed it, a “head rag tax” (kopvoddentaks).57 From 2010 onwards, Wilders has also repeatedly compared the Quran to Hitler’s Mein Kampf and called for banning the Muslim holy book.58 In 2010, he proposed a plan to close down all Dutch mosques in which violence was preached, a position that was further developed in the PVV manifesto for the 2017 election, wherein the party proposed to close down all Dutch mosques. By then, “de-Islamizing the Netherlands” had become “the core” of Wilders’ policy agenda.”59

Conversely, the FVD manifesto for the 2017 general election—which emphasizes democratic renewal, national sovereignty, and tougher immigration measures—does not mention the word “Islam.”60 In fact, Baudet explicitly kept his distance from “raw” PVV-like stances and prohibitions. According to the FVD leader, “Wilders, in his sincere concern about the rights and freedoms of this country, sometimes goes too far.”61 Rather than criticizing Islam as such, Baudet considers himself “a critic of Islamism, the political Islam.” Contrary to Wilders, he is “convinced that within the entire Islamic tradition there are all sorts of points of departure for a much more pleasant interpretation of that religion.”62 This is not to say that the FVD leader never denounces Islam-related phenomena, such as radical imams, Islam-inspired terrorist attacks or “big ostentatious mosques.”63Yet, in contrast to Wilders’ structural and radical alarmism, this critique is of a more sporadic and qualified nature.

At the same time, Baudet’s adoption of relatively prudent public positions concerning Islam are not necessarily a product of electoral considerations or “more refined” political convictions. Rather, they should primarily be perceived in the light of potential physical threats. This, at least, is what Paul Cliteur, Professor of Jurisprudence at Leiden University and President of the FVD’s parliamentary group in the Senate, suggested when I asked him about Thierry Baudet and Islam. “Taking a more critical or negative view of Islam is dangerous,” Cliteur explained, “as we can infer from the protection of Wilders, the murder of Van Gogh, or the summary execution of the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo.”64 Referring to his 2019 book Theoterrorism v. Freedom of Speech, in which he analyses the difficulties governments have in guaranteeing the safety of citizens critical of Islam,65 Cliteur argues that “the only thing that is really safe, is saying that Islam is a peace-loving religion, just like all other religions. That is why you often hear that last position.” At a more fundamental level, then, Baudet and Wilders may not differ significantly. According to Cliteur, who defended Geert Wilders in the latter’s “fewer Moroccans” trial in 2016 and acted as Thierry Baudet’s doctoral supervisor:

“The major opposition is not so much between those denouncing political Islam and those pointing at Islam as such as a problematic factor, but between those who believe that the ideology, the religion, the political religion, the culture (however one wants to call it) constitutes a problem, and those who deny any ideological or cultural factor.”66

This thinking echoes Baudet, who claims that differences between his party and the PVV “are not that important anyway.”67 The FVD leader states that “left-wing parties just have to leave, and once that job is done, we’ll quibble in a new coalition about small differences.”68

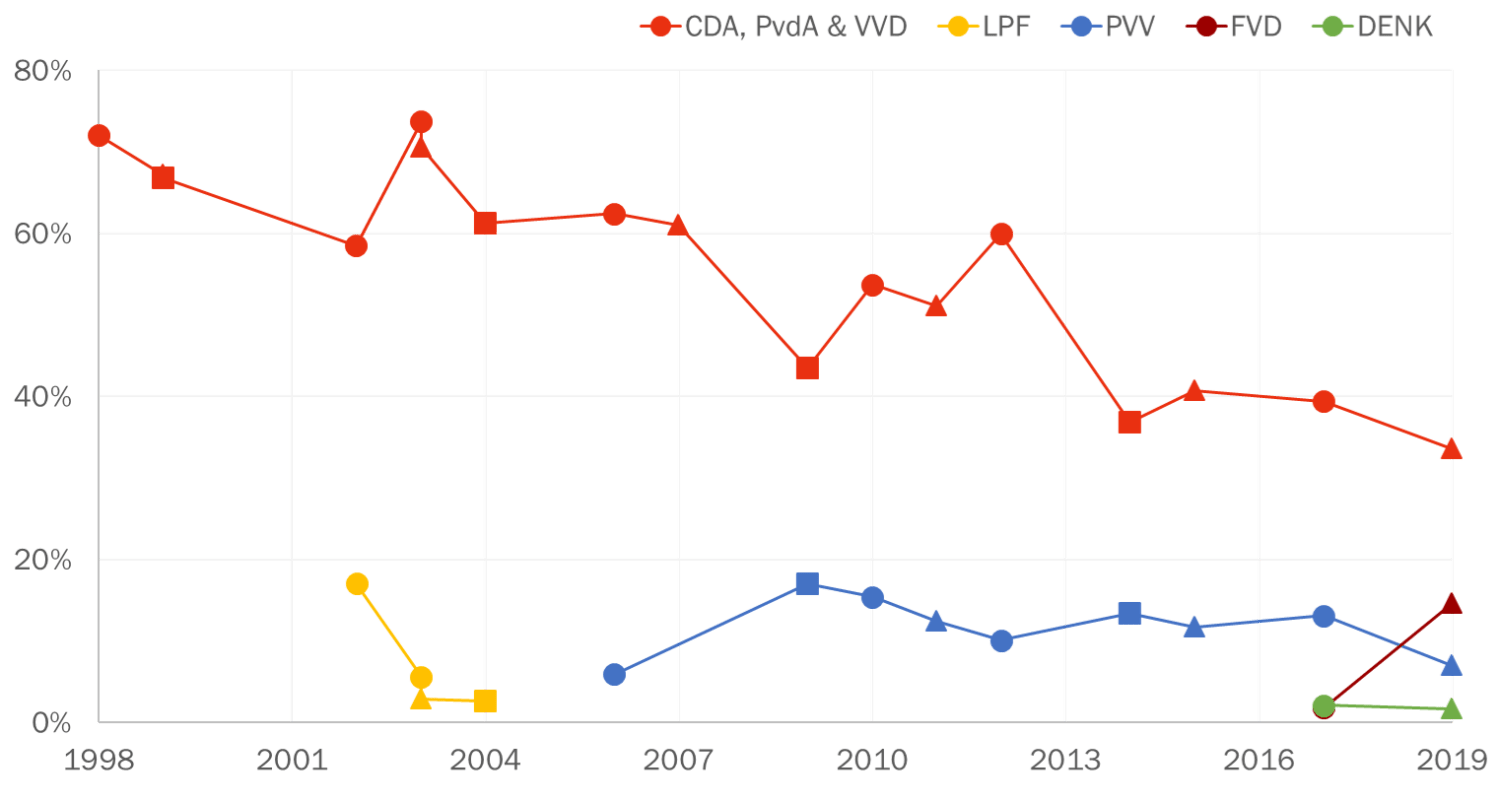

Fueled by similar attacks on political elites in general and left-wing parties in particular, concerns about cultural identity, immigration, and integration have become more salient in recent decades. From a near-total political consensus (or rather silence) in the 1980s and 1990s, establishment parties—from the social democratic Partij van de Arbeid or PvdA, to the Christian democratic CDA to the liberal-conservative VVD—have hardened their stances on immigration and Islam in an attempt to temper the electoral successes of Fortuyn, Wilders and, more recently, Baudet’s FVD.69 Thus far, however, their strategy has not paid off: the PvdA has been decimated and only received 5.7 percent of the vote during the 2017 general elections, while the CDA obtained a mere 12.4 percent. In this increasingly fragmented political landscape—where the three parties that have governed the Netherlands since the late 1940s —only represented a third of the voters in the 2019 provincial elections, as Figure 1 illustrates, the largest party is not a large party any longer.

Figure 1. Percentage of Dutch political party vote share from 1998-2019

Note: Figure 1 includes provincial elections (triangles), national elections (circles) and European Parliament elections (squares).

In moving to the right on immigration and Islam-related issues since the sudden success of the LPF in 2002, Dutch mainstream parties alienated substantial groups of voters with migrant backgrounds.70 During the 2017 election, many of these citizens found a new electoral home in DENK, meaning “think” in Dutch and “equal” in Turkish. Founded in 2015 by two former Social Democratic MPs, DENK explicitly presents itself as a party “many Muslims will feel comfortable with,” as well as “non-Muslims who reject the cold right-wing [political] climate.”71 With 2.1 percent of the votes, it became the first immigrant party ever to gain seats in a national parliament of a European Union member. Studies show that DENK voters come mainly from the morally conservative segments of the well-organized Turkish-Dutch Muslim community. In addition, the party has managed to mobilize the votes of citizens of Turkish and Moroccan origin who are increasingly frustrated and disappointed with Dutch mainstream parties and the exclusionary turn of their discourse—especially the PvdA, which has historically attracted many voters of migrant backgrounds.72

The rise of the PVV, FVD, and DENK illustrate the increasing polarization around immigration, integration, Islam and—to various extents—the European Union, which, as mentioned previously, is framed by the PVV as a boon to Islamization.73 The perceptions, both real and imagined, of increasing cultural differences not only have political implications; rather, they also have societal consequences, as symbolic boundaries between different groups are accentuated more and more profoundly by parties on both sides of the political spectrum. In this context, the “Western European way of life and that of Muslims” are deemed “incompatible” (onverenigbaar) by a growing segment of the Dutch: 39 percent of the population in 2008 through 2009, and 45 percent in 2017. Simultaneously, an increase in religiosity among Dutch Muslims over the same period is evident. For instance, according to a major survey conducted by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP), the share of Dutch citizens from Turkish origin praying five times per day increased from 72 percent in 2006, to 85 percent in 2015 (69 to 78 percent for Dutch citizens of Moroccan descent), while the share of Dutch women with Moroccan roots wearing a headscarf increased from 75 to 89 percent (remaining stable around 50 percent for Dutch women of Turkish origin). Meanwhile, the percentage of Dutch-Turkish citizens attending Mosque at least once a week increased from 35 to 40 percent (and 35 to 37 percent among Dutch-Moroccan citizens).74 Moreover, faith constitutes by far the most important declared social identity of these citizens, more than their Dutch nationality.75

Behind these increasingly politicized group identities, however, lurks an impressive diversity—both on the side of PVV voters and among citizens of immigrant background in the Netherlands. To start with the former: far from all Wilders voters are principally preoccupied with the issue of Islamization, as I found in personal interviews I held with 64 PVV voters between September 2015 and July 2016. To be sure, immigration is an electoral consideration of practically all these citizens. Yet, the issue is articulated differently by different subgroups within the party’s constituency who contrast their national “we”-identity to various non-native outgroups. For instance, PVV voters contrast themselves to “lazy Greeks,” “privileged refugees,” “criminal Moroccans,” and culturally “maladjusted Muslims.”76 Some PVV voters do not even see a fundamental difference between the Catholic faith and Islam, such as a 30 year-old non-religious party supporter, who told me that Catholicism “is one big fairy tale. Just like all other religions.”77 Similarly, Jelle Hiemstra, the former campaign leader of the PVV in the northern province of Friesland, explained that he “couldn’t care less about that whole fuss about Islamization.”78 In other words, not all PVV supporters share the same standpoints, while sometimes even openly discrediting or disagreeing with the party they vote for.79

Diversity also characterizes Dutch citizens with a migrant background, and increasingly so. A recent report published by the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy(WRR) showed that the origin of migrants who arrived in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2016 is quite different than previous immigration waves in the second half of the twentieth century. The study even points at an emigration surplus—more emigrants than immigrants—for Turks, Moroccans, and Surinamese during this period. The top 15 migrant groups today consist of Poles, Syrians, persons from the former Soviet Union, Bulgarians, Chinese, Indians, Eritreans, Spanish, Hungarians, Greeks, and Iranians, respectively. As a consequence, not only is the relative share of Muslims among migrants lower than it was in previous decades, their countries of origin are also more diverse.80

Remarkably, despite the increasing identity-based polarization characterizing Dutch politics and the decreasing social coherence in Dutch neighborhoods due to higher levels of ethnic heterogeneity,81 the share of Dutch citizens stating that there are too many people with a different nationality living in the Netherlands has dropped in the past decades, from more than 50 percent in 1999, to less than a third in 2016 through 2017.82 Nevertheless, immigration and integration steadily figure among the top issues worrying Dutch citizens.83 In addition, and in line with the increasing focus on socio-cultural themes in the political debate,84 a growing share of the Dutch population perceives social conflict in ethnic terms, that is, between citizens with a migrant background (allochtonen) and those without (authochtonen); a perceived conflict outnumbering any other, such as poor versus rich, young versus old, men versus women, or working class versus middle class.85 Echoing Bolkesteijn’s prediction from the early 1990s, it is thus likely that the issues of immigration, integration and Islam will continue to feature high on the list of political priorities in the years to come.

-

Footnotes

- Tobias den Hartog and Hans van Soest, “Ik kies voor eigen land eerst, dat is politiek,” interview with Geert Wilders, Algemeen Dagblad, November 5, 2016, https://www.ad.nl/nieuws/ik-kies-voor-eigen-land-eerst-dat-is-politiek~ae1cab1f/.

- Marine Le Pen, for instance, never speaks about “Islam” as such, but about “Islamism.” The possibility for Wilders to be publicly explicit and radical in his anti-Islam stances is fostered by the proportional Dutch political system. In majoritarian systems, such as in France, politicians need to appeal to a wider range of voters to be elected. Accordingly, they cannot be as radical in their proposals as Wilders, who, with only one percent of the votes would still get re-elected.

- Jan Lucassen and Rinus Penninx, Newcomers: Immigrants and Their Descendants in the Netherlands 1550-1995 (Amsterdam: het Spinhuis, 1998); Leo Lucassen and Jan Lucassen, Vijf eeuwen migratie. Een verhaal van winnaars en verliezers (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2016). According to the Central Office for Statistics, three million foreign immigrants were added to the Dutch population between 1972 and 2003, half of which originated from non-Western countries. See, Andries de Jong, “Schatting aantal westerse en niet-westerse allochtonen in de afgelopen dertig jaar,” (The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2003).

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, “Jaarrapport integratie 2016,” (The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2016), https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/_pdf/2016/47/2016b5_jaarrapport_integratie_2016_web.pdf.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, “Asielverzoeken; nationaliteit, vanaf 1975,” (The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2019), https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/80059ned/table?ts=1556869636366.

- Roel Jennissen, Godfried Engbersen, Meike Bokhorst and Mark Bovens, “De nieuwe verscheidenheid. Toenemende diversiteit naar herkomst in Nederland,” (The Hague: Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, 2018), https://www.wrr.nl/binaries/wrr/documenten/verkenningen/2018/05/29/de-nieuwe-verscheidenheid/V038-De-nieuwe-verscheidenheid.pdf.

- Willem Huijink, “De religieuze beleving van Moslims in Nederland. Diversiteit en verandering in beeld,” (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2018), https://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=54392a12-ee29-4d6e-85af-220321fc3dea&type=org.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, “Bevolking; Islamieten en hindoes in Nederland, 1 januari,” (The Hague: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2004), https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/70086NED/table?ts=1556869365168 .

- Ton Bernts and Joantine Berghuijs, God in Nederland (Utrecht: Ten Have, 2016).

- Although the concept ‘radical right’ is not free from (axiological) imperfections, its adjective, ‘radical’, has a unique feature in comparison to other designations of this party family. By virtue of its etymology – i.e. the Latin noun radix (root) -, it is able to accommodate four crucial partisan traits in one sole word, namely: 1.) radical criticism and demands regarding the cultural and economic status quo, based on radicalized versions of mainstream values; 2.) a radical positioning in the political field in relationship to ‘establishment’ parties; 3.) the use of a radical communication strategy through language and discourse; and 4.) radical ‘right’ in terms of anti-egalitarianism based on cultural roots, that is, of nativism as the defining feature of the concerned parties’ ideology. See Koen Damhuis, Roads to the radical right. Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands (Florence: European University Institute, 2018), 4.

- Hanspeter Kriesi, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey, West European Politics in the Age of Globalization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 154-182.

- The counter-mobilization against parties promoting anti-immigration stances has been particularly vigorous in the Netherlands compared to other European countries. See, Paolo Ignazi, “The Netherlands: A Fleeting Right Extremism,” in Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). See also, Ruud Koopmans and Paul Statham, Challenging Immigration and Ethnic Relations Politics: Comparative European Perspectives (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). For official results of elections see, “Verkiezingen,” Kiesraad, https://www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl/verkiezingen.

- Dietrich Thränhardt, “Conflict, consensus, and policy outcomes: Immigration and integration in Germany and the Netherlands,” in Challenging Immigration and Ethnic Relations Politics: Comparative European Perspectives, eds. Ruud Koopmans and Paul Statham (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 162-186.

- For an intellectual portrait of Bolkesteijn and his importance for the conservative movement in the Netherlands, see Merijn Oudenampsen, De conservatieve revolte (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2018).

- Frits Bolkesteijn, De goede vreemdeling. H.J. Schoo-lezing 2011 (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011), 36. Original text: Frits Bolkesteijn, “On the collapse of the Soviet Union,” (speech, Liberal International Conference, Luzern, September 6, 1991).

- See e.g, Kees Brands and Willem Hogendoorn, Van vreemde smetten vrij. De opkomst van de Centrumpartij (Bussum: De Haan), 90, 111; Tom van der Meer, “De Verkiezingen van 2017 in meerjarig perspectief,” in Aanhoudend wisselvallig. Nationaal Kiezersonderzoek 2017, eds. Tom van der Meer, Henk van der Kolk and Roderik Rekker (Stichting Kiezers Onderzoek Nederland, 2018),10-21, http://www.dpes.nl/images/AanhoudendWisselvalligNKO2017V4.pdf.

- Pim Fortuyn, Tegen de islamisering van onze cultuur: Nederlandse identiteit als fundament. (Uithoorn: Karakter, 1997).

- “Verkiezingen,” Kiesraad, https://www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl/verkiezingen.

- See Koen Vossen, Rondom Wilders. Portret de PVV (Amssterdam: Boom 2013), chapter 6.

- Martin Bosma, De schijn-élite van de valse munters. Drees, extreem rechts, de sixties, nuttige idioten, Groep Wilders en ik (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2010), 29.

- Ibid., 226.

- Lucas Benschop, “De mooiste tijden voor de PVV liggen nog voor ons,” interview with Geert Wilders, NU.nl, March 9, 2014, http://www.nu.nl/politiek/3721400/demooiste-tijden-pvv-liggen-nog-ons.html.

- Author interview with Johan Driessen, October 17, 2016, in Koen Damhuis, Wegen naar Wilders. PVV-stemmers in hun eigen woorden (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 2017), 176.

- Koen Damhuis, Roads to the radical right. Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands (Florence: European University Institute, 2018).

- Frits Bolkesteijn, De goede vreemdeling. H.J. Schoo-lezing 2011 (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2011), 35.

- Alissa Rubin, “Reclusive Provocateur and Icon of Far Right Rises Before Dutch Vote,” New York Times, February 27, 2017.

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Geert Wilders, “Democratiseer het Midden-Oosten,” Trouw, March 27, 2004, in Koen Vossen, Rondom Wilders. Portret van de PVV (Amsterdam: Boom, 2013), 37.

- Partij voor de Vrijheid, “Een Nieuw-realistische visie,” PVV.nl, 2006, https://www.pvv.nl/index.php/component/content/article.html?id=707:een-nieuw-realistische-visie.

- “De agenda van hoop en optimisme. Een tijd om te kiezen: PVV 2010-2015,” (Partij voor de Vrijheid, 2010), https://www.parlement.com/9291000/d/2010_pvv_verkiezingsprogramma.pdf; “Hún Brussel, óns Nederland. Verkiezingsprogramma 2012-2017,” (Partij voor de Vrijheid ,2012), http://pubnpp.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/FILES/root/verkiezingsprogramma/TK/pvv2012/PVVTK2012.pdf.

- “Gedoogakkoord VVD-PVV-CDA” (The Hague, Netherlands: Rijksoverheid, 2010), 20, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/rapporten/2010/09/30/gedoogakkoord-vvd-pvv-cda/gedoogakkoord-vvd-pvv-cda.pdf.

- Geert Wilders,“Inbreng Wilders bij debat Algemene Politieke Beschouwingen,” PVV.nl, September 19, 2007, https://www.pvv.nl/12-in-de-kamer/spreekteksten/475-inbreng-wilders-bij-debat-algemene-politieke-beschouwingen.html.

- “De agenda van hoop en optimisme. Een tijd om te kiezen: PVV 2010-2015,” (Partij voor de Vrijheid, 2010), 6-7.

- Ibid., 5.

- Tobias den Hartog and Hans van Soest, “Ik kies voor eigen land eerst, dat is politiek”, interview with Geert Wilders, Algemeen Dagblad, November 5, 2016, https://www.ad.nl/nieuws/ik-kies-voor-eigen-land-eerst-dat-is-politiek~ae1cab1f/.

- Author interview with Auke Zijlstra, June 19, 2016, in Koen Damhuis, Wegen naar Wilders. PVV-stemmers in hun eigen woorden (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers), 189.

- Renaud Camus, Le Grand Remplacement (Neuilly-sur-Seine: Éditions David Reinharc, 2011).

- Geertwilderspvv, Twitter post, April 2, 2017, 4:33 a.m., https://twitter.com/geertwilderspvv/status/848498563214700544.

- Geertwilderspvv, Twitter post, August 29, 2017, 9:04 p.m., https://twitter.com/geertwilderspvv/status/902381341001560064.

- Geert Wilders, “Oordeel zelf Tijd voor de Bevrijding,” Algemeen Dagblad, November 5, 2016, 10-11. The Dutch party leader thus echoes Samuel Huntington’s famous idea, initially coined by Bernard Lewis, of a “clash” between Islamic civilization and “our Judeo-Christian heritage.”

- “De islam is een achterlijke cultuur,” interview with Pim Fortuyn, De Volkskrant, February 9, 2002, https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/pim-fortuyn-op-herhaling-de-islam-is-een-achterlijke-cultuur~bee400ca/.

- See also, Ernst van den Hemel, “(Pro)claiming Tradition: The ‘Judeo-Christian’ Roots of Dutch Society and the Rise of Conservative Nationalism”, in Transformations of Religion and the Public Sphere: Postsecular Publics, Rosi Braidotti, Bolette Blaagaard, Tobijn de Graauw and Eva Midde (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2014), 53-76, and De conservatieve revolte, Merijn Oudenampsen (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2018), chapter 7.

- Koen Damhuis, Roads to the radical right. Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands (Florence: European University Institute, 2018), 193-4. For an illustration of these public positions, see an interview with Marine Le Pen in L’Émission politique, “Marine Le Pen supprimera le Mariage pour Tous si elle est élue (F2, 09/02/17, 22h)” YouTube video, “pascale2laballe,” February 11, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnPM1rj9tZo.

- Koen Vossen, “Classifying Wilders: The Ideological Development of Geert Wilders and His Party for Freedom,” Politics 31, no. 3 (2011):187.

- Olivier Roy, L’Europe est-elle chrétienne ? (Paris: Seuil, 2019), 148.

- Koen Damhuis, Roads to the radical right, 118-9.

- Geertwilderspvv, Twitter post, April 13, 2015, 5:35 a.m., https://twitter.com/geertwilderspvv/status/587594977200443394.

- Geertwilderspvv, Twitter post, November 14, 2015, 3:50 a.m., https://twitter.com/geertwilderspvv/status/665496905451991040.

- Geert Wilders, Marked for Death: Islam’s War Against the West and Me (Washington: Regnery Publishing Inc., 2012), 7-8.

- Author interview with a PVV volunteer, November 5, 2018.

- Martin Bosma, De schijn-élite van de valse munters. Drees, extreem rechts, de sixties, nuttige idioten, Groep Wilders en ik, 226.

- “De agenda van hoop en optimisme. Een tijd om te kiezen: PVV 2010-2015,” 6.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- E.g., “Analyse Forum voor Democratie,” (I&O Research, September 2017), https://ioresearch.nl/Portals/0/Analyse%20Forum%20voor%20Democratie.pdf; Maurice de Hond, “PS2019 naar demografische kenmerken en kranten lezen,” (March 2019), https://www.noties.nl/v/get.php?r=pp191105&f=PS2019+NAAR+KENMERKEN.pdf.

- Eefje Oomen, “Nederland kan nog veel meer Thierry Baudet gebruiken,”Algemeen Dagblad, May 19, 2018, magazine 8-14.

- “Wilders wil ‘kopvoddentaks,’’ Trouw, September 16, 2009, https://www.trouw.nl/home/wilders-wil-kopvoddentaks-~ad027ad3/.

- Geert Wilders, “Genoeg is genoeg: verbied de Koran,” De Volkskrant, August 8, 2007, https://www.volkskrant.nl/nieuws-achtergrond/genoeg-is-genoeg-verbied-de-koran~b014930c/.

- Tobias den Hartog and Hans van Soest, “Ik kies voor eigen land eerst, dat is politiek,” interview with Geert Wilders, Algemeen Dagblad, November 5, 2016, https://www.ad.nl/nieuws/ik-kies-voor-eigen-land-eerst-dat-is-politiek~ae1cab1f/.

- “Concept Verkiezingsprogramma 2017-2021,” (Forum voor Democratie, 2017), https://forumvoordemocratie.nl/Verkiezingsprogramma%202017.pdf.

- Wouter de Winther and Lise Witteman, “Het ideologische debat ontbreekt,” interview with Thierry Baudet, De Telegraaf, May 5, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Eefje Oomen, “Nederland kan nog veel meer Thierry Baudet gebruiken,” interview with Thierry Baudet, Algemeen Dagblad, May 19, 2018, magazine 8-14. For an example of a critical, Islam related tweet, see, thierrybaudet, Twitter post, August 31, 2017, 11:19 a.m., https://twitter.com/thierrybaudet/status/903321243117654016.

- Author’s e-mail correspondence with Paul Cliteur, February 1, 2019.

- Paul Cliteur, Theoterrorism v. Freedom of Speech. From Incident to Precedent (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

- Author e-mail correspondence with Paul Cliteur.

- Eefje Oomen, “Nederland kan nog veel meer Thierry Baudet gebruiken.”

- Ibid.

- See, Hanspeter Kriesi, Edgar Grande, Martin Dolezal, Marc Helbling, Dominic Höglinger, Sven Hutter and Bruno Wüest, Political Conflict in Western Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 96-126.

- Floris Vermeulen, “The paradox of immigrant political participation in Europe amidst crises of multiculturalism,” in The Oxford handbook of migration crises, eds. Cecilia Menjívar, Marie Ruiz, and Immanuel Ness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Thijs Niemantsverdriet, “Ook veel niet-Moslims zijn het gure rechtse klimaat zat,” NRC Handelsblad, Febuary 9, 2015, cited in Simon Otjes and André Krouwel, “Why do newcomers vote for a newcomer? Support for an immigrant party,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies (January 2018):6.

- Floris Vermeulen, Eelco Harteveld, Anja van Heelsum and Aad van der Veen, “The potential of immigrant parties: insights from the Dutch case,” Acta Politica (November 2018).

- In the past few years, this polarization is also fuelled by extra-parliamentary organizations, such as Erkenbrand (alt-right) and the transnationally operating movement Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident).

- Willem Huijink, De religieuze beleving van Moslims in Nederland. Diversiteit en verandering in beeld (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2018), https://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=54392a12-ee29-4d6e-85af-220321fc3dea&type=org.

- Werelden van verschil. Over de sociaal-culturele afstand en positie van migrantengroepen in Nederland, Eds.Willem Huijnk, Jaco Dagevos, Mérove Gijsberts and Iris Andriessen (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2015).

- Koen Damhuis, Roads to the radical right. Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands (Florence: European University Institute, 2018).

- Author interview with a PVV voter, July 10, 2016, cited in Koen Damhuis, Wegen naar Wilders. PVV-stemmers in hun eigen woorden (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers), 112.

- Cited in Koen Vossen, Rondom Wilders. Portret van de PVV (Amsterdam: Boom, 2013), 160.

- See, for instance, Chris Aalberts, Achter de PVV. Waarom burgers op Geert Wilders stemmen (Delft: Eburon, 2012), 70- 74.

- Roel Jennissen, Godfried Engbersen, Meike Bokhorst and Mark Bovens, De nieuwe verscheidenheid. Toenemende diversiteit naar herkomst in Nederland (The Hague: Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, 2018), https://www.wrr.nl/binaries/wrr/documenten/verkenningen/2018/05/29/de-nieuwe-verscheidenheid/V038-De-nieuwe-verscheidenheid.pdf.

- Ibid., see also Roel Jennissen, “Het is niet anders: etnische diversiteit hangt samen met minder cohesie in de buurt,” Sociale vraagstukken, January 16, 2019, https://www.socialevraagstukken.nl/het-is-niet-anders-etnische-diversiteit-hangt-samen-met-minder-cohesie-in-de-buurt/comment-page-1/.

- Paul Dekker and Josje den Ridder, “Publieke opinie,” in De sociale staat van Nederland 2017, eds. Rob Bijl Jeroen Boelhouwer Annemarie Wennekers (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2017), 75.

- Josje den Ridder, Paul Dekker and Evelien Boonstoppel, Burgerperspectieven 2018/3 (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2018), https://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=8f9ca41c-2f22-4343-b44b-b4fd605e4d73&type=org.

- See, Hanspeter Kriesi et al., Political Conflict in Western Europe.

- Paul Dekker and Josje den Ridder, Burgerperspectieven 2019/1 (The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2019), https://www.scp.nl/dsresource?objectid=0a2454ae-8ec2-47b3-bf08-3e1bed04d706&type=org.