The “Third Offset” strategy, officially launched with this year’s budget request, attempts to identify asymmetries between U.S. forces and those of potential adversaries. What role can military innovation play in enhancing U.S. military advantages?

On December 5, the Brookings Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence hosted an event discussing the future of U.S. military innovation with Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work. Alan Easterling of Northrop Grumman and Kelly Marchese of Deloitte Consulting also spoke, and Brookings Senior Fellow Michael O’Hanlon moderated the event.

First, Second, Third Offsets

Secretary Work reminded the audience that the United States has enjoyed a conventional advantage over recent adversaries. Importantly, that advantage has been against small regional powers. There has been less worry about peer competitors since the end of the Cold War, he said, but that has changed again over the past decade.

With an ascendant China and a re-strengthened Russia, a new military strategy called the Third Offset “helps deter a conventional conflict with a large state power,” according to Work. A key facet is strengthening conventional deterrence. In short, the Third Offset is meant to help prevent war with a great power by ensuring that if we did ever fight, we would prevail.

The First Offset, as O’Hanlon outlined, covers the full range of U.S. nuclear capabilities in the 1950s. The Second Offset is more focused on precision weaponry and air-land battle concepts from the 1970s and 1980s. All offsets, Work noted, “are focused on operational and organizational constructs that provide an advantage at the operational level of war.” But the Third Offset is more open-ended, long-term, and diffuse, compared to the first and second offsets. While we knew the end game of the First Offset and the Second Offset as they were developed, we do not necessarily know the end state when it comes to the Third Offset.

We do know that technology—specifically its connectedness to military organizations and to military doctrine—provide the key to the Third Offset. Secretary Work highlighted five areas of focus:

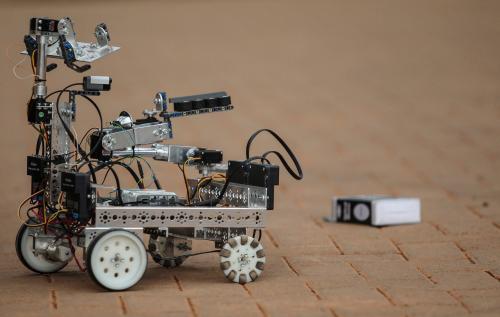

- Learning machines

- Human-machine collaboration

- Assisted human operations (such as exoskeletons and wearables)

- Man-unmanned combat teaming

- Better autonomous weapons

Work stressed the criticalness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and autonomy. “Putting AI and autonomy into the battle network is the most important thing we can do first,” he said. Missile defense, robotics, and unmanned systems also fit into the Third Offset framework, and Work said these systems can be thought of as “assisted human ops” (as distinct from “enhanced human ops,” which involve genetically modifying the soldier; that’s not something the United States is pursuing, but it is possible competitors may try). There is also a clear cyber element to the Third Offset—for one, autonomous machines driven by AI might be the first line of defense in a cyberattack.

What about possible ethical concerns of these military systems? O’Hanlon queried Secretary Work on the potential for machines making their own decision to shoot. Work indicated that was more likely to happen under authoritarian governments—pointing, for example, to a Soviet conception that was totally automatic. In the United States, he said, our focus has been on enabling better communications and network capabilities for the human warfighters.

The Third Offset, in Work’s view, is not unlike other major revolutions that started in the commercial technology space, such as the telegraph and railroad, which ultimately transformed war.

By land and by sea

Kelly Marchese reminded the audience that the Third Offset is not just about technology, highlighting the importance of overall architecture and integration. According to Marchese, the most important aspects are “operational and organizational constructs.” Since technology changes so rapidly, improving agility and the way technologies interact in a network are also key. Marchese expressed concern that networking standards have not been set.

O’Hanlon pointed out that many networks are unlikely to survive a cyber attack. Could much of our technology be rendered useless in such incidents?, he wondered. Marchese responded: “The good news is much of this technology is still not connected. The bad news is it needs to be connected to operate as effectively as we want.”

Turning to more traditional means of warfighting, O’Hanlon asked Alan Easterling about the oceans, adding that they are thought of as an “area of great promise” in the international arena. Easterling agreed, but emphasized that there’s a problem with ships. Modern ships are very vulnerable, he said—during the Falklands War of 1982, for example, superior British ships proved little match for advanced missiles. That is very much the story today, Easterling added, saying: “Any surface vessel within 1,200 miles of determined opponent is at risk.” And this problem tends to push everyone underwater. In many ways, he said, submarines are the “last bastion of stealth.” There are still unresolved difficulties under water, though (including communication), and concluded that combining above and below water assets remains key.

Finally, O’Hanlon turned to land bases and their vulnerability. He pointed out that there are things we can do like hardening, dispersal, and retaining short-takeoff aircraft to help overcome the issues. But is this enough? Easterling argued that the best strategy is distribution, and that forward bases are often quickly overwhelmed, adding: the “age of the medium range ballistic missile changes everything.” Circling back to remarks by Secretary Work, Easterling remarked that the United States has not faced a foe with this kind of capability, and that it is of great potential concern.

While some challenges lie ahead, the overall message of the event was that the Third Offset strategy or its natural successor, whatever that may be called (but which will likely preserve many elements of the Third Offset), will offer considerable hope for the United States in the decades ahead.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Technology and the “Third Offset” foster innovation for the force of the future

December 9, 2016