COVID-19 has kept more than 168 million children around the world out of school for more than one year, but as schools reopen it is important not to forget another stubborn and powerful barrier keeping children out of the classroom—distance.

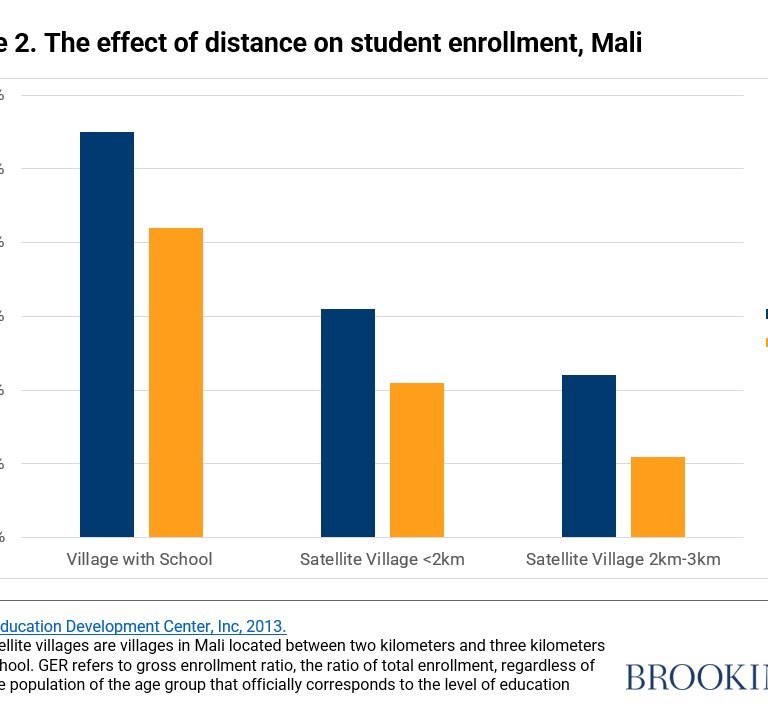

According to the World Bank, “The single most important determinant of primary school enrollment is the proximity of a school.” In country after country, from India to Mali, evidence shows that the farther children are from school, the less likely they are to attend. And as we see in Figures 1 and 2, this is especially true for girls.

Figure 1. Enrollment or completion of grade nine schooling by distance and gender, India

Source: American Economic Journal, 2017.

Source: American Economic Journal, 2017.

Distance to school is a particular challenge for girls in sub-Saharan Africa, where data from eight countries indicates that more than 1 in 4 primary school children live more than two kilometers from the nearest school, while secondary schools for rural students are often hours away on foot.

This long walk to school amplifies the already considerable challenges facing rural girls, including poverty, insecurity, violence, and social norms hostile or indifferent to girls’ education. The walk to school can leave girls vulnerable to harassment and assault and can deepen their family’s poverty by preventing girls from helping on the family farm before or after school. When the walk is in addition to daily chores, such as fetching water, girls may be forced to make part of their journey before dawn or after dusk.

In the face of these challenges, many parents—fearful for their daughter’s safety or concerned about making ends meet—pull their daughters out of school. According to UNESCO, just 1 percent of the poorest girls in low-income countries complete secondary school.

Getting girls to school

A robust global body of evidence has found that getting girls to enroll in school and maintaining attendance for as long as possible is one of the most powerful levers for empowering girls, sparking economic growth, improving health outcomes, and reducing exploitative practices such as child marriage.

Until recently, strategies for increasing girls’ enrollment and attendance focused on three levers: building more schools, lowering school fees, and conditional cash transfers to families. Building more schools can be effective, but in many rural areas this can lead to an educational model based on sub-scale, one-room schoolhouses incapable of delivering high-quality education. Lowering school fees and providing conditional cash transfers to families who enroll their daughters in school does not address the fundamental challenge facing girls—miles and miles of unpaved roads between their home and school.

Evidence that bicycles help girls get to school and stay in school

There is increasing recognition—based on research in Colombia, India, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and a high-quality randomized control trial in Zambia—that bicycles can serve as an effective conditional non-cash transfer to help girls get to and stay in school.

For the last ten years, the Ministry of Education in Zambia has partnered with World Bicycle Relief to help nearly 37,000 rural girls get to school quickly and safely through a cost-effective locally managed program. Girls enrolled in the program sign “service to own” agreements with their community, pledging to complete their studies in return for use and eventual ownership of a bicycle. In addition to providing at-risk rural girls with specially designed bicycles, the program trains local mechanics to keep those bicycles in service for years to come.

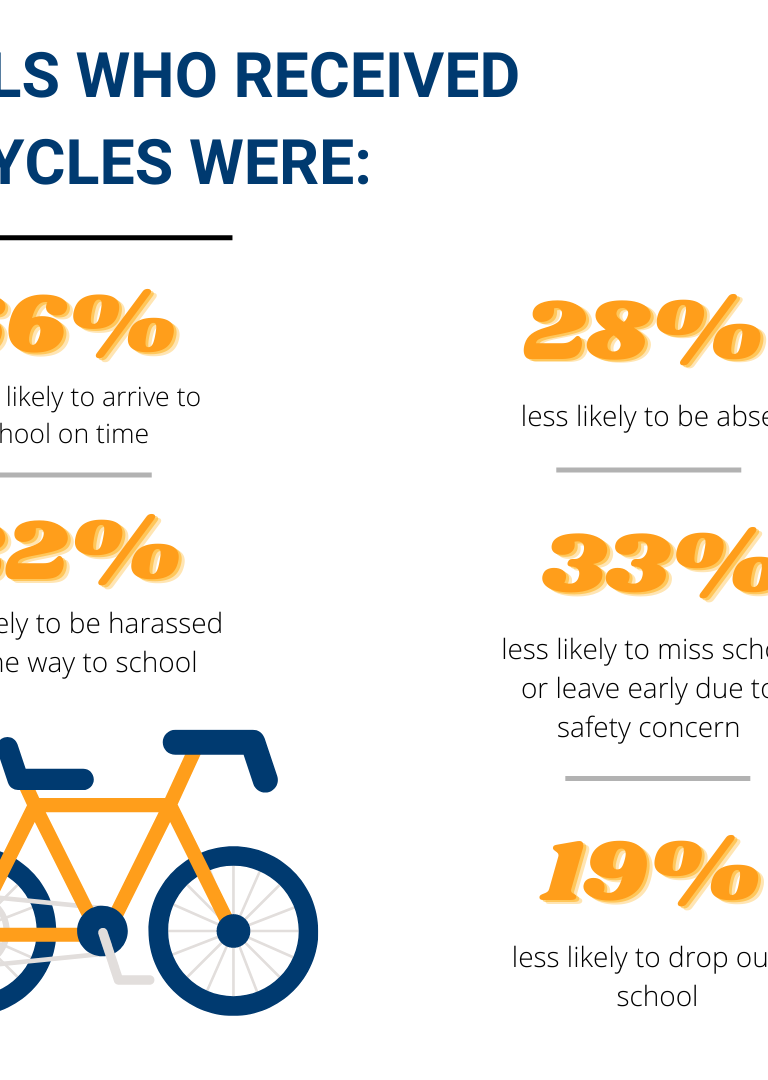

A rigorous randomized control trial and subsequent evaluations of the program found that girls provided with a bicycle cut their commute time by more than an hour a day, reduced their absenteeism by 28 percent, were 19 percent less likely to drop out, and scored higher on mathematics assessments (see Figure 3). They also reported feeling more in control of decisions affecting their lives, ranked themselves higher academically, had a greater belief in their potential to succeed in life, and experienced 22 percent less sexual harassment and/or teasing on their way to school.

Figure 3. Results of WBR’s bicycle program in Zambia

Source: Adapted from World Bicycle Relief, 2022. Designed by Brookings.

One father remarked that his daughter, equipped with a durable specially designed bicycle for the rough terrain, was suddenly “more intelligent.” The heartbreak is that we know she didn’t suddenly gain IQ points. She gained time and energy.

We know all these girls have gifts. Some are brilliant writers, some are creative thinkers, some are math whizzes, and others budding engineers. But when they are exhausted and hungry from their long walks to and from school and fetching water and working on the farm, they are even further challenged to demonstrate or develop that brilliance or talent.

We recognize that durable, fit for purpose bicycles will not ensure every girl gets to school, stays in school, and learns in school. But it is a powerful, low-cost, and sustainable tool effective in many circumstances and geographies that too many governments and funders have—until now—ignored. As schools reopen, the world has one chance to respond with a holistic set of solutions to prevent an entire generation of girls from losing an education due to rural exclusion. In addition to investing in quality learning, let’s reconsider what demands we’re putting on rural girls, lighten their load, and recognize the miles and miles of unpaved roads that stand between them and the world they (and we) want.

Commentary

Riding to school: How bicycles are changing education for girls in rural Africa

July 21, 2022