Debates about corporate income tax cuts follow a familiar script. Republicans claim that rank-and-file workers benefit. Democrats argue that affluent shareholders reap the gains.

In a new project, we find that, workers do benefit, but it is the most affluent employees – managers and executives – who receive the lion’s share of benefits, not rank-and-file staff.

Let’s back up, though. Loosely speaking, corporations are taxed on their net profits. These consist of normal returns—the amount one could expect from a standard market investment—plus excess returns earned from patents, special expertise or some combination of skills, luck, economies of scale, location-specific factors, or market power in products or labor.

Studies suggest that 60 percent or more of the corporate income tax base consists of these excess returns. The TPC model, for example, assumes that normal returns constitute 40 percent of the corporate tax base while excess returns account for the remaining 60 percent.

Who bears the tax on these excess returns? Standard thinking concludes that any tax of less than 100 percent on excess returns still leaves the firm with some excess returns and thus might not affect investment or hiring at all, in which case shareholders are left holding the bag.

There is substantial empirical evidence, however, that firms share their excess returns with their employees. In the old days, this occurred via union strength, but unions and rank-and-file workers have lost bargaining power over the last 60 years.

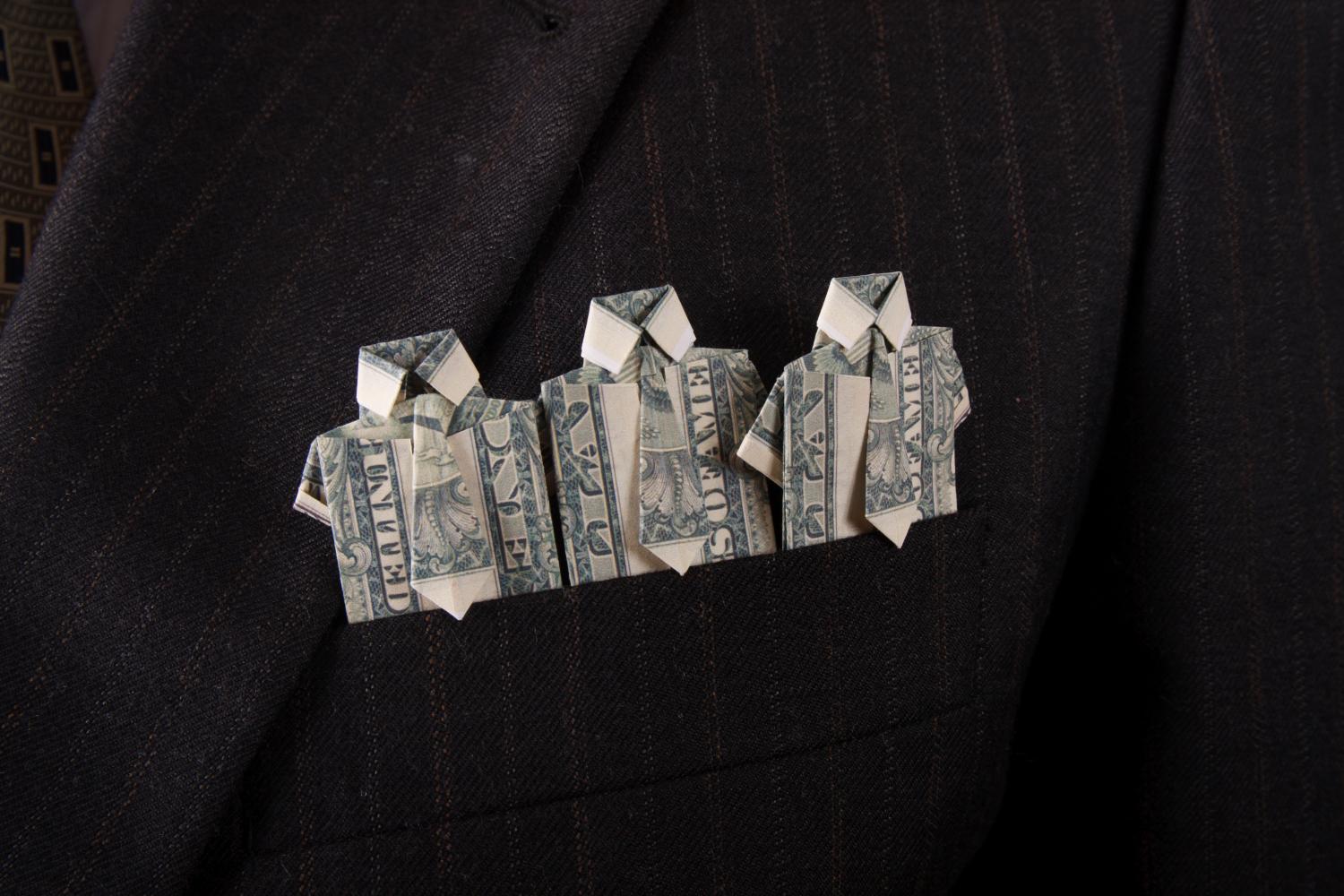

Nowadays, firms share excess profits in different ways: by paying their managers and highly-skilled employees more to retain them; through contracts that link executives’ compensation to firm performance, which are in turn affected by taxes; or through self-dealing behavior on the part of executives.

A study by Eric Ohrn of Grinnell College shows that the five highest-paid executives at the studied firms reaped between 17 and 25 percent of some recent corporate income tax cuts – including changes in depreciation rules and subsidies for domestic production.

Economists at the Federal Reserve Board and the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation found the highest-paid 1 percent of employees reaped 40 percent of the benefits of a corporate tax cut. An additional 19 percent of the benefits of that tax cut went to the highest paid 2 percent to 10 percent of employees. A tall stack of other papers report similar results: While firms share some excess returns with workers, the vast majority of that income goes to high-income employees.

What does this have to do with corporate income taxes? When firms share excess profits with high-income employees, those workers share the benefit of those corporate tax cuts.

We use the Tax Policy Center’s (TPC) microsimulation model to quantify these effects.

The corporate income tax, of course, is one of the most progressive elements of the revenue system. The current TPC model assumes shareholders retain all excess returns and estimates the top 1 percent of tax filers receive 16 percent of income and pay 35 percent of the corporate tax. Similarly, the top 20 percent receive 53 percent of income and pay 70 percent of the tax.

You might expect that reallocating burdens on rent from shareholders to workers would be regressive, since stock holdings are highly concentrated among the very wealthy. But when we adjust TPC’s assumptions to reflect firms sharing rents with high-income employees, the corporate income tax remains approximately as progressive as if shareholders retain all excess returns.

The tax burden on labor rises, but, because the employees affected are disproportionately high-income, the share of the tax borne by highest-income households remains about the same as under standard assumptions.

These findings suggest analysts need to distinguish between rank-and-file workers and professional, managerial, and executive employees when they study the incidence of the corporate tax. Our analysis also has implications for understanding the incidence of value-added taxes or destination-based cash flow taxes, both of which place burdens on excess returns.

Our results also raise other questions. For example, are corporate income tax increases (reductions in excess profits) shared the same way as tax cuts? Does the source of the change in excess profit affect how it is shared? Stand by for future updates.

Download the full report here.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).