President Trump signed an order imposing a 25 percent tariff on steel and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum, with an exemption to Mexico and Canada. Brookings scholars explain the cause of these tariffs, who supports them, and what their consequences will be both on the U.S. domestic and global economy.

What is the argument for tariffs?

Brookings Fellow Joseph Parilla explains that the argument in favor of tariffs is that “they are a counterweight against foreign producers of aluminum and steel that have flooded the U.S. market, putting American companies at a disadvantage. And for those metro areas and states that concentrate steel and aluminum production, this may represent a welcome relief.”

Who supports these tariffs?

Brookings Senior Fellow William A. Galston writes that “If President Trump thinks that imposing steep tariffs on steel and aluminum will boost his public support, he is going to be disappointed.” Galston comes to this conclusion based on a survey by the Chicago Council on Public Affairs which found that 72 percent of Americans thought trade is good for the U.S. economy and 78 percent of Americans thought trade benefited consumers like themselves. This includes even core Trump supporters, of which 62 percent said trade was good for the economy and 68 percent said benefited consumers.

On the steel and aluminum tariffs specifically, Galston finds that only 31 percent of Americans approve of President Trump’s decision.

Brookings Senior Fellow David Dollar explains that these tariffs are controversial because they are justified on national security grounds, because of the negative affect these tariffs will have on some of our allies and trade partners, and because of the possible negative consequences these tariffs could have on the U.S. and global economy.

What are the possible negative consequences?

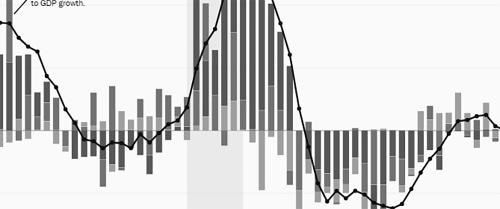

Warwick J. McKibbin, Brookings nonresident senior fellow, notes that a rise in global tariffs would lead to “losses for all.” If tariffs rise 10 percent, it would reduce GDP of most countries between 1 and 4.5 percent, with the U.S. losing 1.3 percent of GDP and China 4.3 percent of GDP.

Many countries have announced that they would impose their own retaliatory tariffs and taxes if the United States implemented the steel and aluminum tariffs Trump suggested. Joseph Parilla notes that China and the European Union have signified that they will respond to these tariffs with their own tariffs on American-made products, which could hurt American exports. The EU in particular has already suggested that they would target bourbon, blue jeans, and motorcycles for these retaliatory measures.

McKibbin also warns that major creditor countries, who buy U.S. treasury bills and other government securities, could decide to sell their holdings and invest in other countries in response to these tariffs. This would cause the value of the U.S. dollar to drop sharply, exports to rise, and imports to fall. U.S. consumers and the government would be worse off due to high borrowing costs but U.S. good would be cheaper to foreigners.

Which states would be hit the worst by the consequences of these tariffs?

Another possible negative consequence would be the effect of higher prices for steel and aluminum imports on the auto manufacturing, brewing, construction, and other industries in the US. Joseph Parilla explains that U.S. imports of steel and aluminum goods accounts for about 2 percent of total U.S. imports, about $48 billion in 2017.

Increased prices for steel and aluminum imports would be especially painful for Missouri, Louisiana, Connecticut, Maryland, and other states’ whose production relies heavily on steel and aluminum imports. In these states, aluminum and steel imports account for at least 5 percent of total state imports, double the share of the nation’s 2 percent total.

Are these tariffs going to lead to a trade war with China?

Ryan Hass explains that many of the factors Washington actors believe will deter a trade war with China are based on flawed assumptions. Hass elaborates with evidence that Chinese President Xi Jinping stands to gain politically by punching back against tariffs imposed by Washington on Chinese goods. Additionally, the importance of the American market to China has declined over the years. Chinese exports to the U.S. only account for three percent of China’s GDP. Instead, Xi is aware that the U.S. is dependent on China to balance North Korea and that a trade war with China would hurt the U.S. economy. Hass analyzes these factors and comes to the conclusion that China will probably respond strongly to U.S. tariffs and use North Korea and other issues as leverage to influence U.S. trade policy.

How can we avoid a trade war with China?

In order to avoid a trade war with China, Ryan Hass suggests that the Trump administration request alternative specific requests from Xi Jinping that Xi could accept. This could include asking Xi to open the Chinese market to U.S. agricultural exports, to accept new commitments on enforcing intellectual property protections, to make new pledges to cut excess capacity production, or other requests.

Hass explains that, this way, Trump could use the major threat of raising steel and aluminum tariffs as leverage in a time-restricted negotiation to get new commitments from Beijing while avoiding a trade war.

For more, see more Brookings global trade content.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Questions about Trump’s new tariffs answered

March 9, 2018