As the COVID-19 pandemic starts its third year, countless institutions are facing questions about a broader return to “normal” operations—including Capitol Hill. In the House of Representatives, proxy voting has served as the chamber’s temporary measure to limit interpersonal mingling between members, especially those with greater health risks. Despite its initial rejection by the House GOP, new data on proxy voting indicates that roughly 80% of all House members used the option through mid-December 2021, suggesting that this rule is now welcomed by both parties as a reform of traditional voting procedures and raising questions about its potential in the future.

After H. Res. 965 was adopted in May 2020, Republican House members responded immediately with significant pushback. Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and 160 other Republican members filed a suit against Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and the House clerk. In his initial arguments in McCarthy, et al. V. Pelosi et al. (2020), the Republicans’ attorney, Charles Cooper, argued that remote voting was wholly unconstitutional; the founding fathers meant for members to be “actually present in their respective offices when they vote.” The legislative process, he contended, demands debate and deliberation, which becomes diluted in a remote format. Any votes cast by proxy, Cooper held, were to be considered “invalid.” The District Court, as well as the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, dismissed the suit and cited the court’s lack of jurisdiction over House rules. The case has been appealed to the Supreme Court, now with only two Congressional plaintiffs (McCarthy and Chip Roy (R-TX)).

Since the lawsuit was originally filed, however, roughly 70% of the original Republican plaintiffs still serving in the 117th Congress participated through December 10, 2021 (either as a designator or designate) at least once. As McCarthy realized his party wanted to avail themselves of the proxy option, he suggested that members remove themselves from the lawsuit if they were planning on voting by proxy. Furthermore, GOP members had observed that Democrats, by emphasizing proxy voting to their members, were losing fewer votes to absent members and could thus more accurately predict final vote tallies on any bill.

who are republicans designating as proxies?

Out of all Republican members of the House, 144 of 213 have designated a proxy to cast their vote at least once in the 117th Congress through December 10, 2021, as opposed to just seven GOP members in the 116th Congress. On average, Republicans voted by proxy 29 times, compared to an average of 54 times for House Democrats. These members using proxy voting in the 117th Congress hail from a wide variety of states and represent a range of ideological preferences within the Republican conference.

Like Democrats, Republican members in this Congress have exclusively chosen proxies from their own party, mirroring the vastly polarized nature of our modern legislature. The average ideological distance between a GOP member and their proxy is smaller than the equivalent average distance between a Democrat and their proxy, possibly reflecting a greater desire among the GOP to collaborate with like-minded peers. And like Democrats, around 50% of Republican members chose proxies who are younger than themselves—a trend consistent with the notion that most members using proxy voting are older members selecting younger, healthier colleagues to be physically present.

tracking republican proxies over time

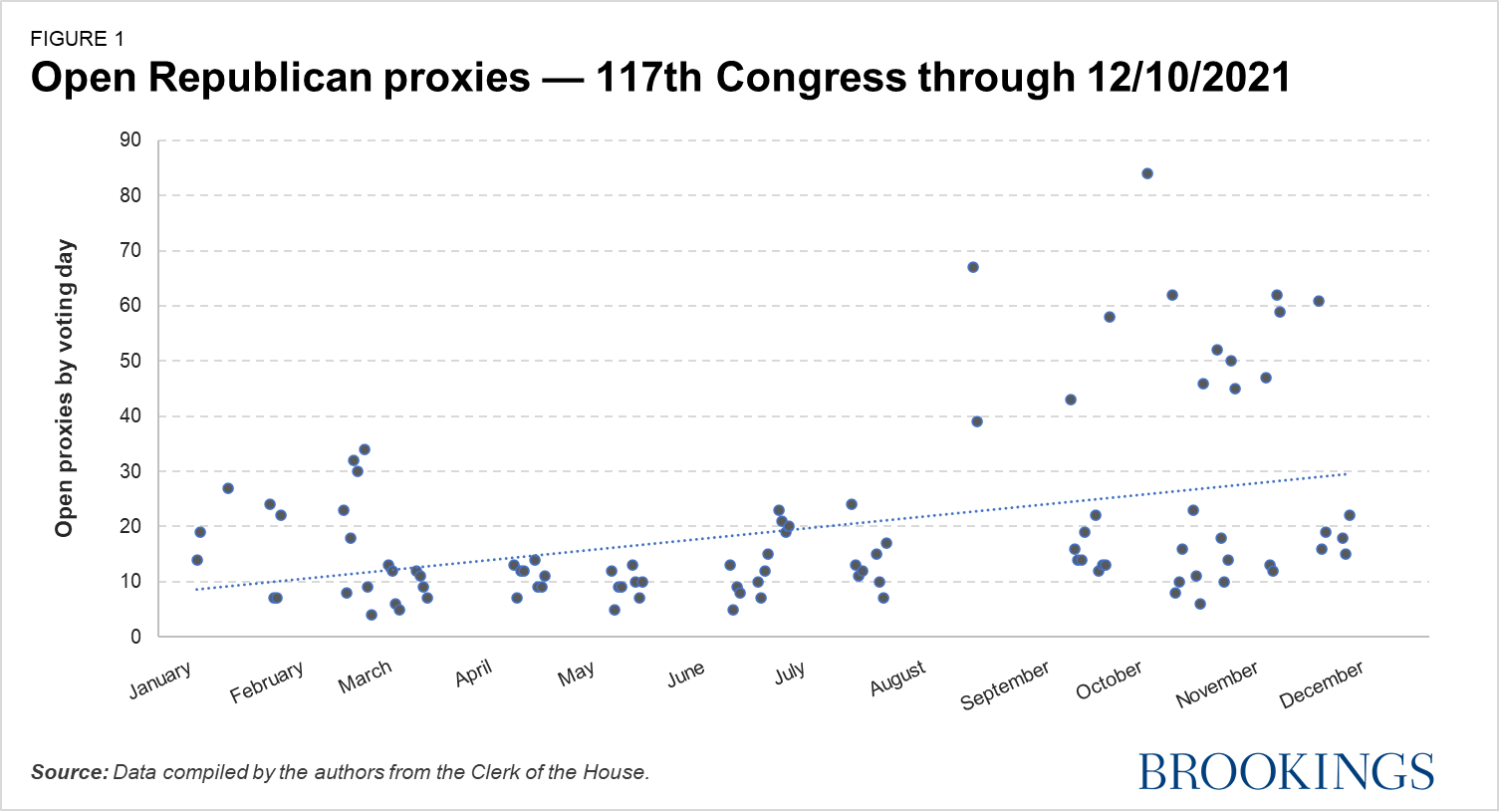

Over the course of the 117th Congress, we have observed an increase in the number of members who have used proxy voting at least once; this is reflected below in Figure 1. Notably, however, most members have availed themselves of the option only intermittently. As we see in Figure 2, as of mid-December, the typical Republican legislator has had an open proxy letter for relatively few voting days—a median of ten and an average of 13—suggesting that members are generally not using proxies to remain away from Washington for long stretches of time. By comparison, the typical Democrat has had an open proxy letter for a median of 13 and an average of 19 days.

Importantly, certain votes have seen exceptionally high numbers of proxy voters. The November vote on the Build Back Better legislation, for example, saw very high usage of proxy voting despite being one of the most significant votes of the year. Notably, 56% of the 98 members who used a proxy during this vote were Republican.

The future of proxy voting

At its inception, proxy voting was conceived of as a way for members of Congress who are “unable to physically attend proceedings in the House Chamber due to the ongoing public health emergency” to cast their votes. But as proxy voting usage has continued, members from both parties have pushed the envelope on the scope of the rule and continue to use the practice frequently; from December 1-10, there were, on average, 21 Democrats and 12 Republicans voting by proxy on a given vote. And while the data presented here runs only through December 10, 2021, the continuing prevalence of the omicron variant has kept proxy voting rates high.

Indeed, many members do still consider proxy voting an imperative for certain health risks. Representative Donald Payne from New Jersey, for example, has still voted almost exclusively by proxy because as a diabetic, operating at an in-person capacity would pose a greater risk to his safety.

Nonetheless, other members have taken this opportunity to partake in activities or work outside of Washington, DC, while Congress is in session. Some have been transparent about being able to attend important meetings or conferences simply by sending a proxy letter to the House Clerk. Others have expressed gratitude for the greater time to remain in their district and around their families.

Importantly, even when members are voting by proxy, they are not simply taking a vacation. Most are still performing those duties which they were elected to perform—just from a different location. Beyond voting, committee hearings and meetings still run, with varying degrees of virtual participation. Disregarding the travel time between their home district and the Capitol, representatives are finding themselves less burdened with scheduling conflicts. Members have also expressed content in distancing themselves from lobbyists and interest groups, which commonly take up much of members’ time.

The current proxy voting system will be in place at least through February 13, 2022, thanks to a recent extension by Speaker Pelosi. But as the House considers the longer-term future of remote participation, it must seriously take into consideration the drawbacks of the arrangement as well. Various fundamental components of the legislative process, such as negotiating on amendments and debating on the floor, work differently in an environment where some are physically present and others are not. In addition, any normalization of remote participation for purely discretionary reasons could start a slippery slope whereby members portray virtual engagement as a positive political strategy to avoid “going to Washington”—a trend that would be harmful to the institution as a whole.

At the end of the day, proxy voting has been central to keeping the House largely operational throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Its increase in popularity suggests there may be a demand to make it permanent in some form. But in doing so, the House will have to find a way to balance the rule’s benefits for those who need it over its risks of misuse—a tough feat at best.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Proxy voting takes on new meaning for Republicans

January 20, 2022