“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” This old proverb illustrates well the principle of productive inclusion programs, a relatively recent addition to the toolbox of social policy makers. These programs aim to boost productivity and incomes of the poor and are being presented as an alternative to social safety nets. But can productive inclusion really help graduate people out of poverty, or is it just another development fad?

In the early 2000s, governments around the world rolled out massive conditional cash transfer (CCT) programs. The hope was to dramatically reduce intergenerational transmission of poverty by increasing demand for social services, particularly education and health, which have a well-documented relation to long-term poverty. To a large extent, these programs met expectations as the cash transfer helped reduce poverty. CCTs also raised the demand for education and health services (although the importance of the conditionality is still being debated). Unfortunately, they did not manage to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty, in part because they have shown limits in reaching the ultra-poor, and because beneficiaries do not appear to generate much higher incomes once they leave the program.

A decade later, a new trend is emerging. Once again, the conceptual framework is solid: Long-term poverty reduction can only happen if households can boost their income; hence, the new focus on productive inclusion and the ensuing programs—typically consisting of services to promote self-employment activities among the rural poor and self-employment or wage employment among the urban poor. These programs are rapidly gaining traction around the world under various forms, from training and productive grants in sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe to comprehensive poverty reduction campaigns in Latin America. But do they have a real chance to lift people out of poverty?

Productive inclusion programs in rural areas have shown promising results. A large evaluation of the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and Ford Foundation’s Graduation Programs in Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan, and Peru, all of similar design, finds substantial economic and social impacts. With the exception of Honduras, all programs also have shown positive returns to the initial investment (ranging from 133 percent in Ghana to 410 percent in India). An unsupervised grant program in Uganda led to an increase in earnings of 38 percent. And a randomized experiment giving grants to Sri Lankan microenterprises found returns to capital that are substantially higher than market interest rates.

In urban settings, these programs often take the shape of training and job search and facilitation services for vulnerable groups. Their impacts have been quite diverse and depend on the target population, leading to a debate on the relative advantages of training versus cash. Some of the most vulnerable beneficiaries, such as the unemployed, vulnerable or marginalized populations, and out-of-school youth are harder to train due to psychosocial factors and—in particular for the last two groups—difficult life trajectories that often kept them away from school.

Depending on the package of services, productive inclusion programs can also become relatively expensive to implement. Uganda’s unsupervised grant program provided people with a grant of approximately $375. The costs of Latin American training programs for vulnerable youth varied, in the early 2000’s, between $420 and $750 (in nominal terms), while the more comprehensive CGAP-Ford Foundation Graduation Programs face overall implementation costs ranging between $1,538 and $5,742 per household.

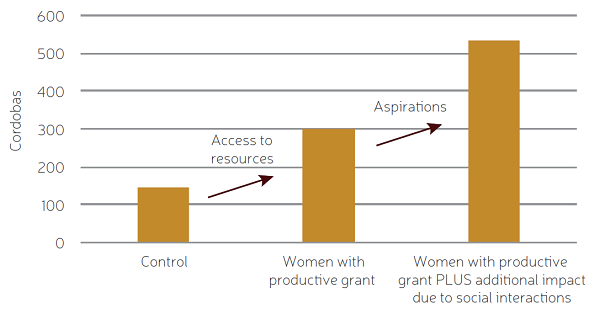

Efficiency gains could be reached from better identifying the channels underlying their impacts. Available evidence points towards the need to associate grants with training; to tailor productive activities and training to the local culture and economy; and, for the ultra-poor, to provide grants as opposed to credit. The psychological and social dimensions of poverty surrounding beneficiaries, such as mental health status, low aspirations, and the lack of role models can also affect the impacts of productive inclusion programs. For instance, social interactions and interfaces with local leaders significantly amplified the effectiveness of a productive grant program for women in Nicaragua. But, overall, little is known on the relative importance of each of these factors—which most likely depends on the context, program design, and beneficiaries’ profile.

Figure 1: Social interactions can lift aspirations and the impacts of productive inclusion

Note: Impacts of a productive grant program with and without social interactions. The Cordoba is Nicaragua’s national currency. Source: Macours and Vakis (2014).

Summing up, productive inclusion programs are a great supplementary tool for social policy makers. But they are not a silver bullet: While, especially in rural areas, they can make a dent in reducing poverty, neither safety nets nor productive inclusion programs alone will solve the poverty challenge. Ultimately, lifting people out of poverty requires a combination of policy actions, ranging from supporting economic growth to improving education and social policies. It is important to have realistic expectations on the possible impacts of both productive inclusion and social protection programs. For instance, one cannot expect that training programs for vulnerable youth, which on average last three to nine months, to be a substitute for years of education, even of relatively poor quality. Rather, their impacts must be gauged against what they really are: remedial programs for serious structural gaps. As such, productive inclusion should not be implemented in isolation. It is a more powerful tool if it becomes part of a broad and multi-sectoral poverty reduction strategy and of an integrated social protection system that tailors solutions to the needs and vulnerabilities of beneficiaries.

Acknowledgments: This blog draws substantially from works the author has written with Adriana Camacho, Wendy Cunningham, Jennifer Hennig, Pablo Lavado, Leonardo Lucchetti, Edmundo Murrugarra, Veronica Silva, Renos Vakis, Gustavo Yamada and Melissa Zumaeta. All errors are the author’s.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Productive inclusion: A silver bullet, or a new development fad?

April 12, 2016