The following brief is part of Brookings Big Ideas For America—an institution-wide initiative in which Brookings scholars have identified the biggest issues facing the country this election season and are providing individual ideas for how to address them.

President-elect Trump has repeatedly declared his desire to make peace between Israelis and Palestinians “for humanity’s sake,” viewing it as the “ultimate deal,” and suggesting that he would appoint his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, as his special envoy for this purpose. He would not be the first American president to hear the siren song of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, but he would be the first real estate developer to try to reach for the “brass ring,” and his experience with making land deals as well as his unconventional, disruptive approach to diplomacy might just generate new possibilities when all other efforts have failed. However, President Trump would be taking on the task at a uniquely difficult moment when neither side trusts in the peaceful intentions of the other or believes in the possibility of a peace deal based on the establishment of a viable Palestinian state living alongside the Jewish state of Israel in peace and security.

President-elect Trump has repeatedly declared his desire to make peace between Israelis and Palestinians “for humanity’s sake,” viewing it as the “ultimate deal,” and suggesting that he would appoint his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, as his special envoy for this purpose. He would not be the first American president to hear the siren song of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, but he would be the first real estate developer to try to reach for the “brass ring,” and his experience with making land deals as well as his unconventional, disruptive approach to diplomacy might just generate new possibilities when all other efforts have failed. However, President Trump would be taking on the task at a uniquely difficult moment when neither side trusts in the peaceful intentions of the other or believes in the possibility of a peace deal based on the establishment of a viable Palestinian state living alongside the Jewish state of Israel in peace and security.

This “two-state solution” has been thwarted by two abiding realities that would have to be fundamentally altered for its chances to be revived. The first is the power of the Israeli settler movement and its supporters in Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition government. They regard all West Bank territory as part of the Land of Israel and firmly reject the two-state solution. Consequently, they are pursuing apace an effort to annex the 60 percent of the West Bank that remains under complete Israeli control (known as “Area C” in the Oslo Accords that govern Israel’s relations with the Palestinian Authority) through expanding settlements there, attempting to legalize some 50 outposts that are illegal under Israeli law, and preventing any Palestinian development of the land.

The second reality is a politically and physically divided Palestinian polity in the West Bank and Gaza Strip between the Hamas and Fatah political parties, in which Hamas remains dedicated to the destruction of Israel and is consolidating its grip on Gaza while building its influence in the West Bank. Meanwhile, Fatah is going through a succession process which has left its leadership preoccupied and, for the time being, unable to engage in any kind of peace initiative.

In other words, there are two powerful forces—the Israeli settler movement and the Hamas Islamist movement—that are driving toward one-state solutions of their own design. However momentarily attractive these alternatives may look to people on either side of the conflict, they cannot produce a peaceful solution brought about by a negotiated deal between the two sides. Indeed, such a negotiated peace deal is anathema to both of them. Little wonder they have done all they can—the one through settlement activity, the other through violence and terrorism—to thwart the negotiations that have taken place. Their solutions do not solve the conflict between the two peoples that inhabit the same land. On the contrary, they are bound to perpetuate it.

Nevertheless, these realities constrain both Prime Minister Netanyahu and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) from engaging in meaningful peace negotiations. Netanyahu’s right-wing coalition would collapse if he were to pursue territorial concessions in the West Bank. The alternative of forming a more flexible centrist coalition with the Labor Party would leave him dependent on parties to his left while his rivals to his right robbed him of the support of his natural constituency. Meanwhile, Abbas’s electoral mandate expired some six years ago, and he no longer feels he has the legitimacy to make compromises over what his people believe are their inalienable rights. If he attempted to do so, he would be denounced as a traitor by his rivals in Hamas and Fatah alike.

This situation generates an acute policy dilemma: current circumstances do not permit the achievement of a negotiated resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and yet failure to pursue that resolution now will make it even less possible to achieve it in the future. In attempting to address this dilemma, President-elect Trump and his would-be special envoy would do well to heed the lesson of the last attempt by Secretary of State John Kerry (in which I served as his special envoy to the negotiations): American willpower alone, no matter how artful, cannot substitute for the will and ability of the parties themselves to make the politically costly and emotionally fraught compromises necessary to achieve the deal. And yet another failed effort will not only make matters worse, potentially sparking a new round of conflict, but also tarnish the credibility of the new president, making him look like a loser.

American willpower alone, no matter how artful, cannot substitute for the will and ability of the parties themselves to make the politically costly and emotionally fraught compromises necessary to achieve the deal.

If President-elect Trump is nevertheless intent on trying his hand at the “mother of all deals” despite all these difficulties, he might do well to choose from three options:

- “Jerusalem first”

Given the President-elect’s penchant for throwing away the established rule book, he could adopt a completely novel, high-risk approach designed to inject a new and very different dynamic. One of the basic rules of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations is that the status of Jerusalem is an issue that should be left until all the other issues are resolved. Negotiators have learned from bitter experience that the room for compromise there is more limited than on any other issue. The 2000 Camp David negotiations collapsed over Jerusalem, sparking the second intifada that resulted in the deaths of thousands of Palestinians and Israelis.

The reasons for the intractability of the Jerusalem issue are quite clear: neither side accepts the legitimacy of the other’s claims. Arab east Jerusalem was annexed to Israel in 1967, and since then every Israeli government has claimed undivided Jerusalem as “the eternal capital of Israel.” Jewish suburbs have been built throughout east Jerusalem, cutting the city off physically from the West Bank, leaving only one area (known as E1) that can still connect the two territories. Conversely, Palestinians claim all the area of east Jerusalem that Israel occupied in 1967, including the Old City, as the capital for their state, and view the Jewish suburbs built there as illegal. Both sides also demand sovereignty over the area in the Old City known as the Temple Mount to Jews, and the Haram a-Sharif to Arabs and Muslims. That area contains the Al-Aqsa mosque, the third holiest site in Islam, and the Western Wall and the ruins of the Second Temple that lie behind it, the holiest site in Judaism. The fact that Islam and Judaism both lay religious claim to the same holy area makes touching this issue in negotiations particularly sensitive and potentially explosive.

Rational solutions to all these competing and overlapping claims have been developed. For example, the undivided city could become the shared capital of the two states. Jewish suburbs would be under Israeli sovereignty, Arab suburbs would be under Palestinian sovereignty, and the Palestinian state would be compensated with equivalent land swaps for the land in east Jerusalem on which the Jewish suburbs were built. The area bounded by the walls of the Old City, which contains the sites holiest to the three great religions (including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre), would be declared a special zone where neither side would exercise their claims to sovereignty and a special regime would instead be established to administer the area, ensure freedom of access to all the holy sites, and maintain the religious status quo in which the three religious authorities continue to administer their respective holy sites. However, such rational compromises have not proven remotely acceptable to either side.

President Trump could decide to ignore all these obstacles and instead adopt a strategy of “Jerusalem first.” He could begin by announcing that he had decided to move the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, as he promised to do during the election campaign. This would likely spark an explosion of anger in the Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim worlds, and generate a rallying cry for Islamic extremists everywhere. American embassies and American citizens in Muslim countries would likely be targeted by violent demonstrators. Confrontations between Palestinians and Israelis would likely erupt in the West Bank, and the Palestinian security forces would likely stand aside, unable or unwilling to continue cooperating with their Israeli counterparts to tamp down the violence. Hamas might resume rocket attacks from Gaza, but because of fear of an Israeli response they would more likely seek to stoke the fires of violent resistance in the West Bank and Jerusalem. Arab and Muslim states would likely demand that Trump rescind the decision.

Alternatively, in parallel with moving the U.S. embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, the president could also announce that he has decided to establish a U.S. embassy to the state of Palestine in east Jerusalem, while opposing any division of the city. This decision would likely provoke an equally vociferous but less violent howl of protest from Israel and its friends in Congress and the organized Jewish community, since it would not only acknowledge Palestinian claims in east Jerusalem but also grant recognition to the Palestinian state, prefiguring Jerusalem as the shared capital of the two states.

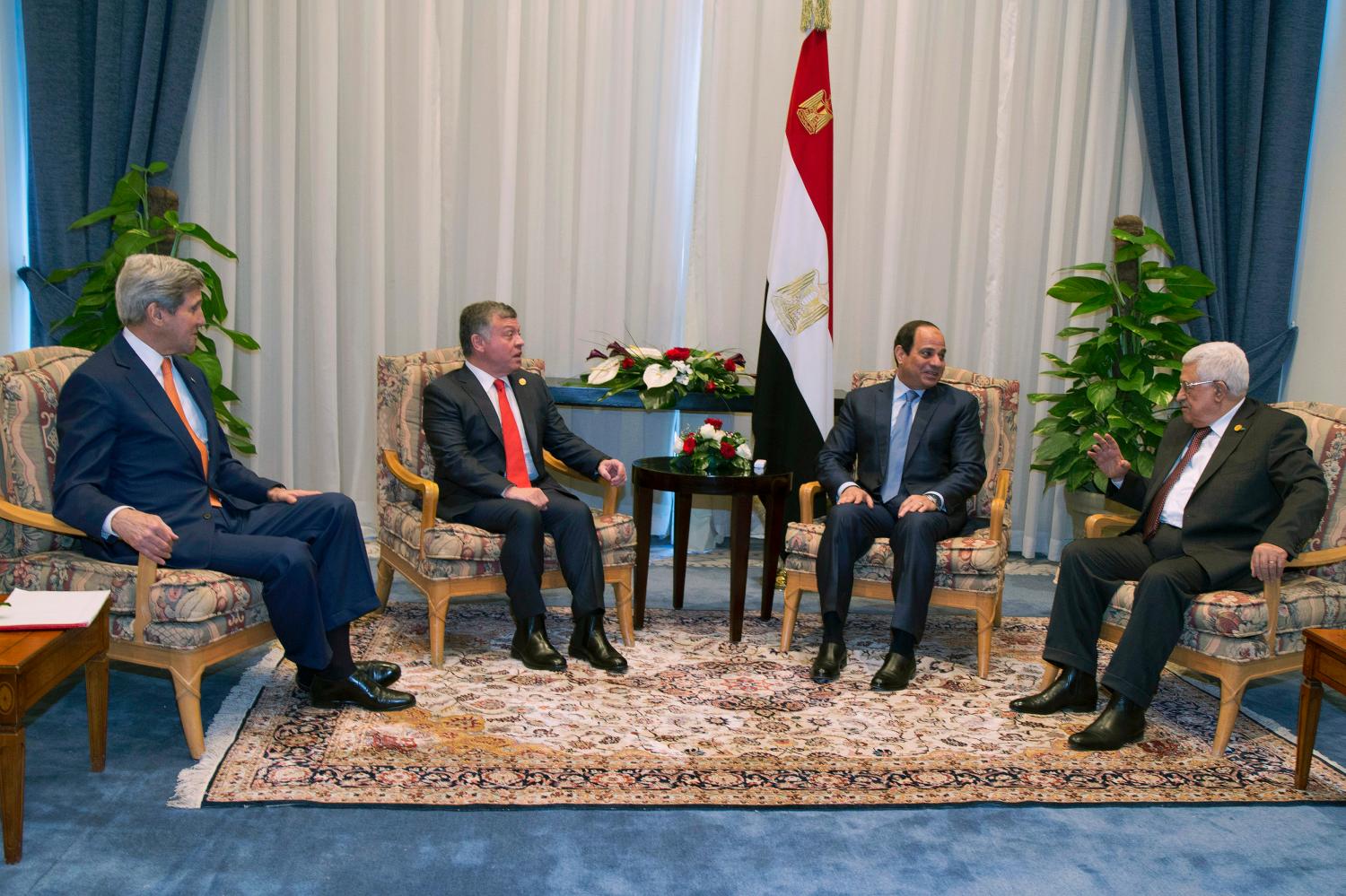

Having provoked the crisis, President Trump could then seek to end it by declaring that he was willing to suspend U.S. recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital (and as Palestine’s capital, in the alternative approach) until both sides resolved its status. He would then need to summon Israeli and Palestinian leaders to Washington to begin direct negotiations on the issue of Jerusalem. President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi of Egypt and King Abdullah of Jordan and the other members of the Quartet (the European Union, Russia, and the United Nations) would need to be invited to join President Trump in overseeing the negotiations to lend weight and legitimacy to the effort. And a short timetable, perhaps three months, would need to be established to conclude the negotiations, during which time there would need to be a construction freeze in east Jerusalem.

To ensure that both sides negotiated in good faith, President Trump could declare that if they fail to turn up or fail to reach agreement, the Quartet, Egypt, and Jordan would resort to a UN Security Council resolution setting out the parameters of the rational solution on Jerusalem, in effect threatening to impose it on the two sides. Israel would be required to accept a Palestinian capital in Arab east Jerusalem in return for Arab, Muslim, and international recognition of Israel’s capital in an undivided Jerusalem. The United States could then go ahead and locate two embassies in Jerusalem, one on the west side for Israel and the other on the east side for Palestine. This could then open the way to negotiation of the other final status issues.

It is important to underscore that this is a high-risk, provocative option in which American lives and interests around the world could well be at stake, not to speak of Israeli and Palestinian lives. Once the fire is lit, it may not be possible to extinguish it by a diplomatic initiative. But if President Trump is determined to go ahead with his promise to move the U.S. embassy to Jerusalem, then wedding it to a preplanned diplomatic effort to resolve the conflict is more advisable than just battening down the hatches and hoping that the storm of adverse reaction will pass.

- Bottom-up

President Trump could instead choose a more conventional effort that attempts to use time to shape a more favorable negotiating environment, laying the groundwork for a negotiated solution later in his presidency. In his first two years, he would instead focus on arresting the negative dynamics on the ground in the West Bank and work with Egypt and Jordan to promote a united Palestinian leadership with a mandate to negotiate peace with Israel.

Under this option, he would need to insist at the outset that Israel stop all construction east of the security barrier that it has built that runs more or less parallel to the 1967 lines inside the West Bank and incorporates the major Israeli settlement blocs as well as east Jerusalem. The right-wing Israeli defense minister, Avigdor Lieberman, has already offered a similar deal to President-elect Trump. Construction in the blocs west of the barrier could continue without American objection. Construction in east Jerusalem could also continue but on a 1:1 basis for building in Arab as well as Jewish suburbs. There could be no construction in E1 or other sensitive areas such as Givat Hamatos which would block east Jerusalem’s connection with the West Bank in the south. Israel also would have to agree to handing over significant territory in Area C, contiguous to the Palestinian-controlled Areas A and B, to allow for Palestinian construction and development. If the Netanyahu government prefers to continue settlement construction in Area C beyond the barrier, President Trump should make clear that he is willing to have the United States abstain on a settlements resolution in the UN Security Council that would declare settlement activity illegal. Prime Minister Netanyahu cannot say so, but he needs this threat to constrain the settlers in his governing coalition. Trump’s insistence on this approach might precipitate a change in Prime Minister Netanyahu’s coalition, since it would be unacceptable to Naftali Bennett’s Jewish Home Party but it has been one of the preconditions for Isaac (“Buji”) Herzog to bring the Labor Party into the coalition. With Jewish Home out and Labor in, Netanyahu would be more capable of entering into meaningful negotiations.

Meanwhile, President Trump would need to work with President Sissi and King Abdullah on generating a change in Palestinian leadership and reconciling Hamas and Fatah on grounds that would enable a unified leadership to enter peace negotiations with Israel. In return, the building of state institutions and the development of the Palestinian economy in the West Bank and Gaza initiated by former Prime Minister Salam Fayyad should be boosted by a new injection of funds from the United States, the Arab states, and the international community.

As these processes on both sides began to take hold, President Trump’s special envoy could begin to talk to both sides about terms of reference for resuming final status negotiations in the last two years of the president’s term. If the Palestinians refused to enter negotiations based on these Israeli constraints on settlement construction, or demanded additional preconditions such as prisoner releases, President Trump could make clear that he would no longer be willing to constrain Israeli settlement activity anywhere.

- Outside-in

If President Trump judges the bottom-up option to be too conventional, slow, and “in the weeds” for a nonconventional leader, he might consider taking up “outside in” approach, which would involve Trump convening the leaders of the Quartet (the United States, Russia, the EU, and the UN) and the Arab Quartet (Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) in a summit meeting to announce a set of agreed principles that would serve as the terms of reference for direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations to achieve a two-state solution. The purpose of convening the summit would be to draw on the collective will of the international community to jumpstart direct negotiations based on these agreed principles.

The principles would need to be based on the final status negotiations that Secretary Kerry conducted, which reflect the requirements of both sides that were articulated in those negotiations. They would need to look something like this:

- The negotiations should lead to an agreement that would end the conflict, end all claims, and establish two states living side by side in peace and security.

- The border between the two states should be based on the 1967 lines with mutually agreed swaps.

- The security arrangements should ensure that Israel can defend itself against any threat, end the occupation that began in 1967, and enable the Palestinians to live securely in an independent, demilitarized state.

- Jerusalem should serve as the shared capital for the two states, with special arrangements to maintain the status quo in the religious sites.

- There should be a just and agreed solution to the Palestinian refugee problem based on UN General Assembly resolution 181 that provided for the establishment of independent Arab and Jewish states in Palestine with equal rights for all their citizens.

Trump would need to be willing to use the goodwill he would gain with these states because of his willingness to adopt a harder line on Iran and political Islam, and a softer line on Egypt, to convince them to join him at this summit.

The Israelis and Palestinians would be invited to attend, but he should not accept their refusal as reason not to convene the summit. Nor should he allow himself to be dragged down into the weeds by agreeing to pre-negotiate the principles with the two sides. That is a well-practiced technique that both sides have deployed repeatedly in the past to bog down a new American president and prevent him from making any progress.

Netanyahu might be attracted by the opportunity to engage with the Gulf states at such a summit, but he will likely be constrained by the right-wing parties in his coalition. The Arab states would have to press the Palestinians to attend. If one side agreed to attend, the other side would come under immense pressure to do so as well. But if only one side were willing to attend, the summit should go ahead anyway, highlighting the recalcitrance of the other side. President Trump might also indicate that if one or both sides were unwilling to attend or begin negotiations based on these terms of reference, then the United States might have to vote for a UN Security Council resolution that incorporated these principles and that called on the two sides to negotiate based on those principles.

No Pain, No Gain

Before President Trump decides to fulfil his desire to make the ultimate deal, it is important that he also be willing to bear the political consequences of doing so. Neither Israelis nor Palestinians at this moment believe that peace is either possible or desirable because the costs seem too high and the benefits too small. For both leaders, the status quo is quite sustainable, even as outside parties fret that the two-state solution is being buried in the process. Moreover, given the nature of his coalition, the maximum that Netanyahu can concede falls far short of the minimum that Mahmoud Abbas will insist upon, given the weakness of his position. There simply may be no zone of possible agreement. Therefore, the president should not assume that this will be an easy lift, his negotiating skills notwithstanding.

For both leaders, the status quo is quite sustainable, even as outside parties fret that the two-state solution is being buried in the process.

Moreover, Israel has a way of extracting a high, upfront political cost via its supporters in Congress if the president makes any effort to apply pressure. Likewise, Palestinian weakness makes it particularly difficult to move them since, like a business venture that is close to bankruptcy, they can always threaten collapse if they are forced to compromise. Meanwhile, the Arab states are all preoccupied with other more serious threats to their security and stability. They will be reluctant to risk Palestinian ire or, for Egypt and Jordan, the unhappiness of their Israeli security partner, to assist the president unless they understand that a final settlement is a high priority for him personally. Even so, none of them will be convinced solely by his confidence that he can do the deal. He will need to embed his effort in a broader strategy for peace and security in the Middle East that is seen to serve their wider interests.

President Trump will therefore have to be prepared to overcome all the local resistance that is now baked into the situation. He will also need to resist the advice of his experts, some of whom will be quick to tell him that this is not a good place to risk his prestige and dissipate his energy, while others will argue that he should just leave Israel to deal with the Palestinians as it prefers. The president does have one thing going for him, however, should he nevertheless decide to ignore the naysayers and try to seize the brass ring: the support of the international community. Except for outliers like Iran and North Korea, there is an international consensus behind the idea of an American-led effort to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Despite all the friction with the Obama administration, Russia has been fully supportive of Secretary Kerry’s efforts, so President Trump can easily find common ground with President Vladimir Putin. Similarly, he will find a willing partner in the EU, which believes that the failure to solve the Palestinian problem exacerbates the other Middle Eastern conflicts that threaten stability in Europe. While the Arab states will be more reluctant to take risks, President Sissi and King Abdullah both strongly believe in the importance of a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict for their own well-being. The Gulf Arabs are less persuadable, but will be attracted by the ability to engage openly with Israel if progress is made in this arena, and that will be an attraction to Israel, too. These converging interests will also help cement the Arab-Israeli cooperation that President Trump will need if he is to get them to share together the burden of restoring stability in the Middle East.

Ironically, then, if President Trump wants to overcome the reluctance of the Israelis and Palestinians to do the ultimate deal, he will need to draw on the support of the international community to achieve it, including the desire of key players, like Putin and Sissi, to work with him. Without their support, he will not have the leverage to move the two sides forward. But if he combines that support with the halo effect of his upset victory, he might just succeed where Clinton, Bush, and Obama have all failed. Just as he dared to be president, he will need to be willing to dare to be the ultimate dealmaker.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).