Media headlines from the past several years tell a clear story: State governments across the U.S. are taking actions to boost housing production and improve affordability. State legislators from Oregon to Montana to Massachusetts have passed laws aimed at legalizing “missing middle” housing and encouraging development of apartments near transit stations. Other states, including Arizona, Colorado, and New York, have debated ambitious bills that failed to cross the finish line. While the political battles make for great storytelling, passing state laws is just the beginning of the next, usually lower-profile process: how local governments incorporate these laws and put them into effect.

To better understand how states are implementing their new policies, in April 2023, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Brookings Metro convened state policymakers and researchers for a series of conversations. This piece summarizes three key lessons from those conversations; a longer report provides more details and state-by-state examples.

Lesson 1: The pathway to implementation is long, and may include snags or detours

Statewide pro-housing policies can take the form of mandates, incentives, or a combination thereof. For example, some require localities to allow duplexes in all residential areas, while others encourage higher-density development near transit stations.

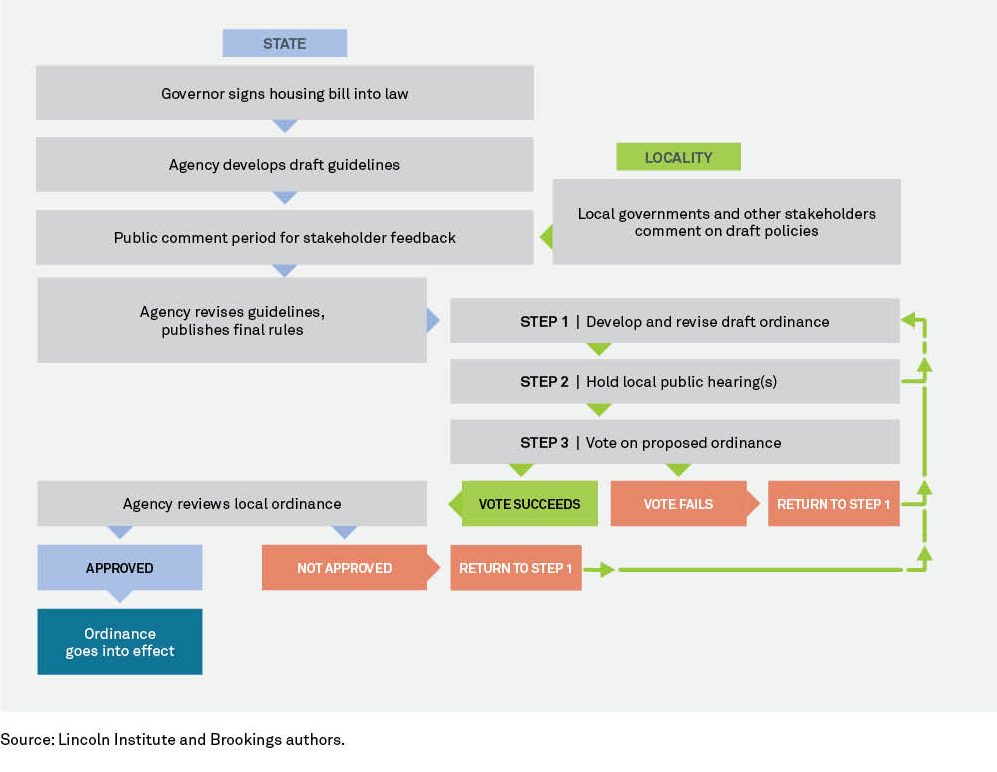

Before taking effect, these guidelines must be incorporated into local laws. The process of doing so varies somewhat across states (or even the type of local government within a state) but follows a general sequence of events (see Figure 1). Action shifts iteratively between state agencies (which issue detailed regulations) and local governments (which revise their laws to comply with the regulations). It can easily take three to four years—or longer, if there is persistent legal or political opposition—from the time the governor signs a bill into law until all affected cities and counties have adopted fully compliant local laws.

Figure 1. Pathways and Bottlenecks: Implementing State Policies

State and local agencies are typically required to present their draft policies for a period of public comment, receiving feedback from stakeholders representing a wide range of opinions. Local elected officials, advocacy groups, and voters that oppose or support the new state policy have opportunities to weigh in—and potentially delay or derail the process of implementation. Media coverage and general public awareness of the issues may also affect the timing and pathways of local policy adoption.

Lesson 2: Successful policy implementation depends on the capacity of state and local governments

Not all state and local governments are created equal, or endowed with equivalent capacity to undertake new projects.

Public entities responsible for overseeing implementation of housing reforms at both the state and local level vary widely in terms of staff capacity (i.e., size, technical expertise, and bandwidth relative to existing duties), financial resources, and related dimensions such as data infrastructure. For example, California’s Department of Housing and Community Development employs a large professional staff, with over 100 people in the policy division alone; meanwhile, Maine’s new law is being implemented by only four staff members across different state agencies. Capacity varies even more among localities: Large, affluent cities and counties typically employ multiple full-time housing policy experts in their planning departments, but many smaller suburban or rural communities have minimal personnel.

To support local governments, states are using a variety of strategies. Issuing clear, detailed guidance on how to incorporate new regulations—including model codes and handbooks—can help avoid confusion. Some state agencies and regional planning organizations offer in-person or virtual trainings for local governments. Funding to hire outside consultants is another option in states where high-quality consultants are available.

Lesson 3: Be clear about the goals new policies are intended to achieve, and how relevant outcomes will be measured

State governments have different reasons for wanting to adopt housing policies, based on underlying housing market conditions and constituent concerns. Being clear upfront about the intended goals and desired outcomes will help during the implementation stage, both in setting expectations for local governments and putting in place systems to collect appropriate data and monitor compliance.

For example, is the primary goal to increase overall housing production, or to create more below-market homes for low-income households? Are there geographic areas of particular interest, such as transit corridors or job- and amenity-rich communities? Each of these strategies implies a slightly different set of metrics that should be tracked to assess the policy’s effectiveness.

Getting implementation right is unglamorous but essential

The excitement and public attention that follow hard-fought political battles over statewide housing policies may fade after legislation is signed into law, but subsequent events are equally important if new policies are to achieve their goals. Understanding the nuts and bolts of how state guidelines are incorporated into revised local laws will help policymakers, the media, and voters develop realistic expectations about when they will see outcomes. Absent this clarity, pro-housing advocates may get discouraged, while opponents claim that zoning changes are ineffective—all before the policies kick in and have time to impact housing supply.

Additionally, policymakers should try to anticipate implementation challenges and design policies that recognize the resources and staff capacity available among state and local governments. State-level housing policies are evolving in real time; researchers and policymakers across the country will be watching to learn what works and what doesn’t.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Passing pro-housing legislation is only the first step in making housing more affordable

September 28, 2023