On October 1, the health insurance exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will open for business. Administrators must complete myriad tasks if they are to serve the millions of individuals — many of whom will be eligible for subsidies — and employees of small businesses who are ready to buy insurance. Initial glitches are likely. Some may be serious. But with good will and persistence, they can be corrected, as Massachusetts’ experience with a law similar to the ACA has shown. That is not the end of the story, however. After the exchanges are up and running, they will be in a position to make decisions that will help shape the organization, quality, and financing of all U.S. health care.

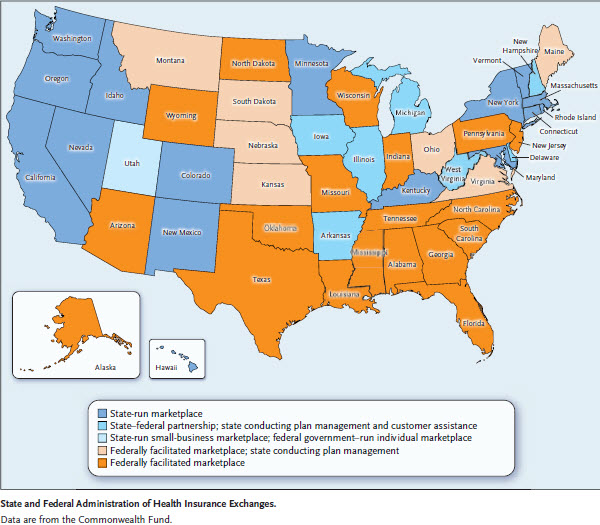

Seventeen states and the District of Columbia are setting up exchanges to enroll individuals, families, and small businesses in health insurance plans, while 33 states will rely on the federal government to do so (Utah is establishing a state-based small-business exchange but will rely on the federal government to operate its individual exchange) (see map1). The tasks confronting the exchanges fall into four broad functional areas: eligibility determination and enrollment, consumer assistance and outreach, plan management, and financial management.1

The ACA establishes income-based categories of eligibility for coverage and financial assistance. People with very low incomes are covered by Medicaid. Others earning up to four times the federal poverty thresholds will be eligible for premium tax credits if they purchase coverage through an exchange and if they do not have an offer of affordable, qualifying employer-sponsored health insurance. Subsidies to reduce cost-sharing obligations will also be made available to some consumers who qualify for premium assistance.

This system is complex and may be confusing to consumers who are largely inexperienced in insurance matters. Different members of a given family may be eligible for insurance coverage through different channels. Eligibility may change as family composition evolves and as income varies. Exchanges need to develop, debug, and maintain software used to enroll people and compute their premium subsidies. They must educate the public about the basic language of insurance (deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, and so forth), as well as the benefits for which they are and are not eligible. They must train people to answer applicants’ questions, staff call centers, and help applicants complete required forms.

Successful implementation of the ACA provisions for expanding coverage hinges on efficient and accurate performance of these administrative tasks. But beyond these challenges lie many other decisions. A few are being made now, but more await future action. Those decisions will shape health care payment and delivery.

The ACA has the potential to create unprecedented competition among insurance plans. Informed consumer choice in the individual insurance markets has never been possible, because companies offer so many plans varying along so many dimensions that few buyers can compare them intelligently. Small businesses have had little leverage in their dealings with large insurance carriers. Their employees have typically been given just one insurance option.

The ACA changes the rules for insurers. They must sell to all willing buyers, regardless of health status. They cannot cancel coverage for those who make large claims. The ACA limits age-based variations in premiums and bans ratings based on health status. It requires plans sold to individuals and small employers to cover a minimum set of medical benefits. It sets up five levels of coverage, defined by the proportion of expected costs a plan will cover. These features are well known.

But the exchanges have additional powers. To limit information overload, they may limit the number of plans insurers can offer and require that plans differ meaningfully from one another. They can require insurers to offer certain standardized plans so that customers can more easily compare price and service. Exchanges can set additional standards for the quality of care paid for by plans, bar plans that do not meet quality or price standards, and selectively contract with those that do. In addition, to strengthen the position of exchanges within the health insurance markets, states may bar the sale of insurance to individuals and small businesses outside the exchanges or require that the same plans be sold inside and outside them.

Few exchange administrators have used many of these powers so far. They have chosen instead to focus on getting the basic administrative details right and have displayed a philosophical and practical caution about overloading insurers with new requirements. After the exchanges are up and running, more of them will be forced — or have the option — to adopt policies that can reshape the financing and delivery of care.

First, the scope of exchange coverage will grow. Starting in 2016, exchanges will have to offer insurance to businesses with 51 to 100 employees. They have that option now, but no state-run exchange will exercise it in 2014. The ACA authorizes the exchanges to consider allowing larger employers, which could include state and local governments, to contract with them for insurance beginning in 2017.

Second, states now have the authority to create a single, unified market for insurance by barring insurance sales to individuals and small businesses outside the exchange. So far, only two jurisdictions — Vermont and the District of Columbia — have elected this course, in an effort to ensure robust participation in the exchange and discourage insurers from trying to siphon younger, healthier individuals into the nonexchange market and directing older, sicker individuals into the exchange. (The District of Columbia requirement for small groups takes effect for plan renewals in 2015.) If the experience of these two jurisdictions is favorable, others may follow suit.

Third, the quantity and quality of information on the prices charged by different hospitals, physicians, and other providers and the availability of data on the quality of care are improving. Exchanges could advertise such information to help consumers make more informed choices or, more aggressively, could require plans to offer incentives for people to use high-quality, low-cost health care services and providers. Exchanges could also create incentives for insurers to encourage or require providers to apply research findings from analyses of comparative effectiveness.

Fourth, the ACA has set in motion a large number of pilot programs, experiments, and demonstration projects involving new methods of paying for care and organizing providers. These innovations include bundled payments and accountable care organizations. Not all these innovations will succeed. But if some do, the exchanges will be in a position to encourage or require their adoption. And if exchanges cover a sizable fraction of the insured population, they will have the clout to change the delivery system.

Fifth, few states have given exchanges the power to contract selectively with particular insurers or health delivery organizations, and fewer exchanges have fully used the power they have. Only six states are requiring insurers to offer standardized plans, and some of the minority of states that are limiting the number of plan offerings have set the cap so high that consumers are likely to experience information overload. If during the early years consumers are overwhelmed by too many options, more states may later adopt more selective approaches to contracting. The federally facilitated exchanges are at the passive end of the scale with regard to most regulatory options.

This list of the ways in which the exchanges may act to transform health care financing and delivery is merely illustrative. Mundane administrative tasks will occupy the exchanges for the first year or two. But the exchanges are an instrument of enormous potential power. Political resistance may inhibit the use of this instrument. But over time, as the initial administrative glitches are ironed out, we believe that the exchanges will be seen as a means for promoting a competitive insurance market in which consumers can make rational decisions and that they will become an instrument that can reshape the health care delivery system.

Footnote

1. Dash S, Lucia KW, Keith K, Monahan C. Implementing the Affordable Care Act: key design decisions for state-based exchanges. New York: The Commonwealth Fund, July 11, 2013 (http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2013/Jul/Design-Decisions-for-Exchanges.aspx).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Only the Beginning—What’s Next at the Health Insurance Exchanges?

September 4, 2013