Individuals who suffer from mental illness are more likely to be injured or killed during police encounters, a problem that is exacerbated by significant racial disparities. New research from assesses New Jersey’s ARRIVE Together pilot, a program that pairs mental health professionals with police for calls involving people suffering from mental health distress.

Analyzing data from 342 police service case calls shows that the ARRIVE Together program demonstrates promising results: reducing both the use of force and arrests and racial disparities in outcomes. Findings also show an increased utilization of social services.

ARRIVE Together has the potential to improve police-community relations, change law enforcement culture, and provide substantive assistance to people suffering from mental health symptoms. This report provides a series of recommendations to streamline data collection and reporting to improve the ARRIVE Together program so it may serve as a model for other states and communities.

Executive Summary

This report analyzes data from 342 police service calls for service and follow-ups involving New Jersey’s ARRIVE Together program, which pairs mental health professionals with police when answering a call that is determined to involve a person suffering from, mental health distress.

The analysis of the pilot program which took place between December 2021 and January 2023 demonstrates promising results:

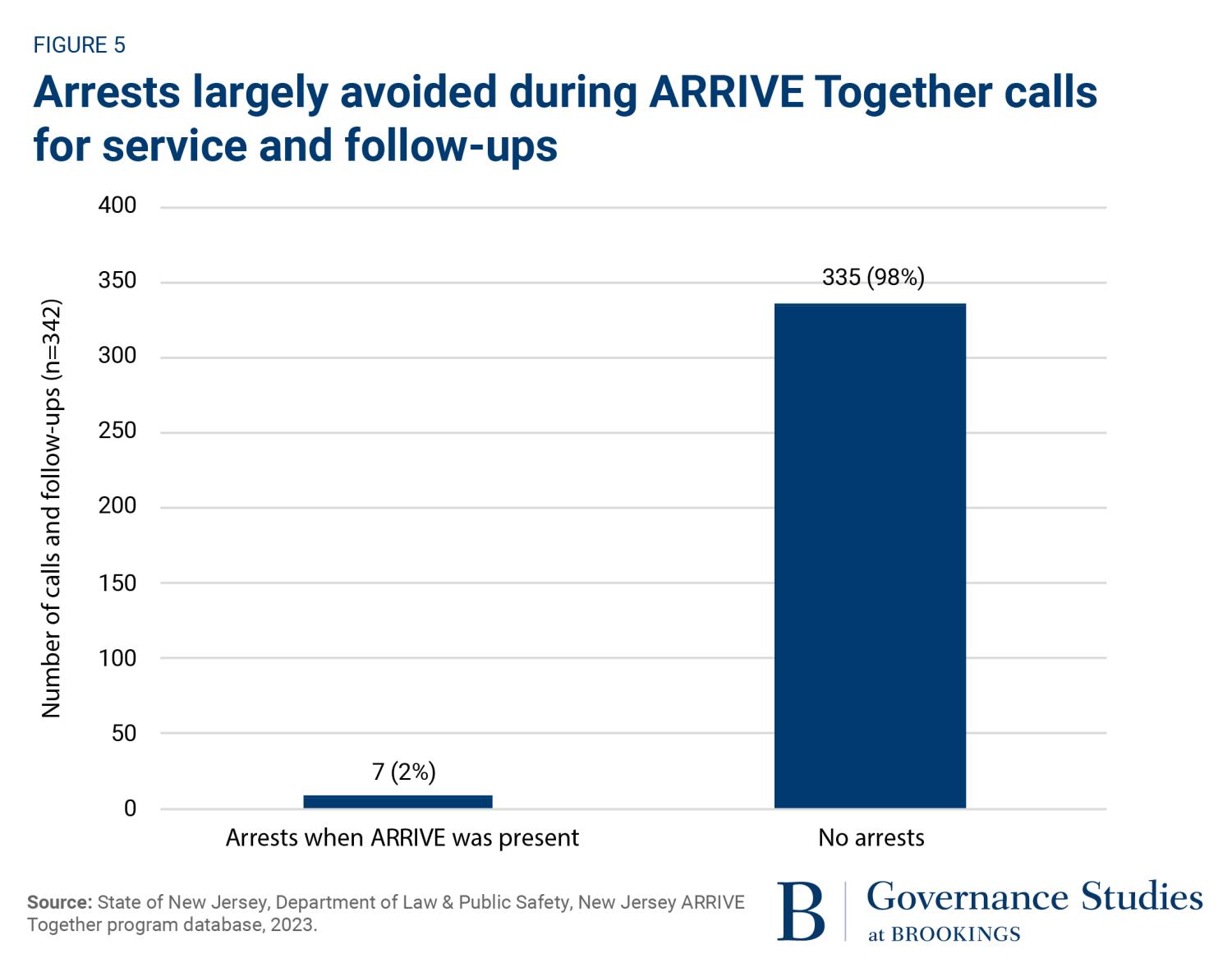

- People suffering from a mental health crisis have a higher likelihood of injury or death during police encounters, 97% of cases did not use force and 98% of cases did not result in an arrest during an ARRIVE Together call for service or follow up. Most of the arrests had to do with criminal activity and not the ARRIVE Together program. The low rate of arrests and use of force is attributed to ARRIVE Together teams’ ability to de-escalate situations and provide expertise on how best to access and utilize mental health services.

- While it is well-known that racial disparities in policing outcomes such as use of force and police killings exist, pilot data from the ARRIVE Together program do not demonstrate any significant differences by the race, gender, or age of the person of interest when it comes to arrival time, requested/dispatching of the ARRIVE team, reporting agency, arrest, or use of force.

Within communities, ARRIVE Together has the ability to help establish and restore trust in law enforcement. Within police departments, ARRIVE Together has the potential to change law enforcement culture in positive ways and provide officers with more strategies in their toolkit to better communicate and interact with the public. The pilot data suggest that the ARRIVE Together program shows much promise and should be expanded and examined across the country.

Background

Nearly a quarter of all people killed by police officers in America were suffering from a known mental illness. We also know that people who suffer from mental illness are more likely to be injured during police encounters. There is anecdotal evidence that botched encounters between police and people in a mental crisis increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the many examples is the recent shooting of a 13-year-old boy with an autism spectrum disorder by Salt Lake City police after his mother called officers to report that her son was having “a mental breakdown.” The teenager is recovering from serious wounds.

“Nearly a quarter of all people killed by police officers in America were suffering from a known mental illness.”

A large percentage of calls for police service implicate both race and mental health. However, rarely is this intersection examined, an omission that was highlighted in the police killing of Leonard Shand in Maryland or even the recent police killing of Najee Seabrooks, a violence intervention activist in Paterson, New Jersey.

More broadly, there are racial disparities in the outcomes of encounters with the police. Black people are significantly more likely than whites to experience use of force and be killed by police. Because of the prevalence of mental health encounters with law enforcement, and the aggravating role that race may play in some of them, scholars, practitioners, policymakers, and even police recognize that reducing encounters between law enforcement and individuals experiencing a mental health crisis may represent one clear strategy for reducing fatal police shootings and use of force in the United States.

Existing research suggests that the presence of mental health professionals during a service call decreases the use of force and arrests, and increases the use of mental health resources. Some police departments have started establishing police/mental health response units. One example is a pilot program in New Jersey, entitled Alternative Responses to Reduce Instances of Violence & Escalation (“ARRIVE Together”), which was launched in 2021 in Cumberland County. The ARRIVE program pairs New Jersey law enforcement with a certified mental health screener to respond together to 9-1-1 calls for behavioral health crises. In 2022, the pilot was expanded to the Elizabeth and Linden Police Departments, the ARRIVE Together program will expand to 36 municipalities across 10 counties. New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy has announced a $10 million per year investment to expand the program statewide.

Beyond New Jersey’s pioneering effort to be the first state to implement a police/mental health co-response program statewide, a number of cities are implementing their own policing improvement efforts to address mental health calls for service. In Denver, Colorado, the STAR program deploys mental health specialists to respond to non-violent, mental health calls. Similar to the state of New Jersey, Murfreesboro, Tennessee created a mental health co-responder crisis intervention team. There are also innovative law enforcement training programs to help police practice identifying mental health issues and de-escalate these situations.

While these efforts show important and needed progress, more work is needed to share what is and what is not working to significantly reduce police violence and killings against this vulnerable population. The opportunity to assess a program in its pilot stages provides an opportunity to both inform scaling options and next steps, while also contributing new resources and best practices for additional pilot programs across the country.

To address this gap in our understanding of the true effectiveness of law enforcement and mental health response units, this report examines calls for service from the ARRIVE Together program in New Jersey. With data on the pilot programs provided by the New Jersey Office of the Attorney General, this report provides an assessment of the program as well as recommendations on additional data points that New Jersey and other states and cities should be collecting for these types of programs.

Accordingly, I ask: do police units that include mental health professionals lead to low levels of arrests and use of force? Are racial disparities in arrests and use of force still present when mental health professionals are included? And, are people referred at high rates to mental health services when calls for service include mental health professionals?

Data

The data analyzed in this report come from three police departments in the New Jersey ARRIVE Together program. The locations of the police departments are very diverse across race and social class relative to other parts of the United States. The areas have similar percentages of whites and non-whites. The cities do vary by population size and location with one being one of the largest cities in the state, another being located close to New York City, and the third city close to the Delaware border. Due to the similarities in the outcomes and to further protect the confidentiality of departments and specific incidents, the data are discussed as a collective rather than disaggregating the departments.

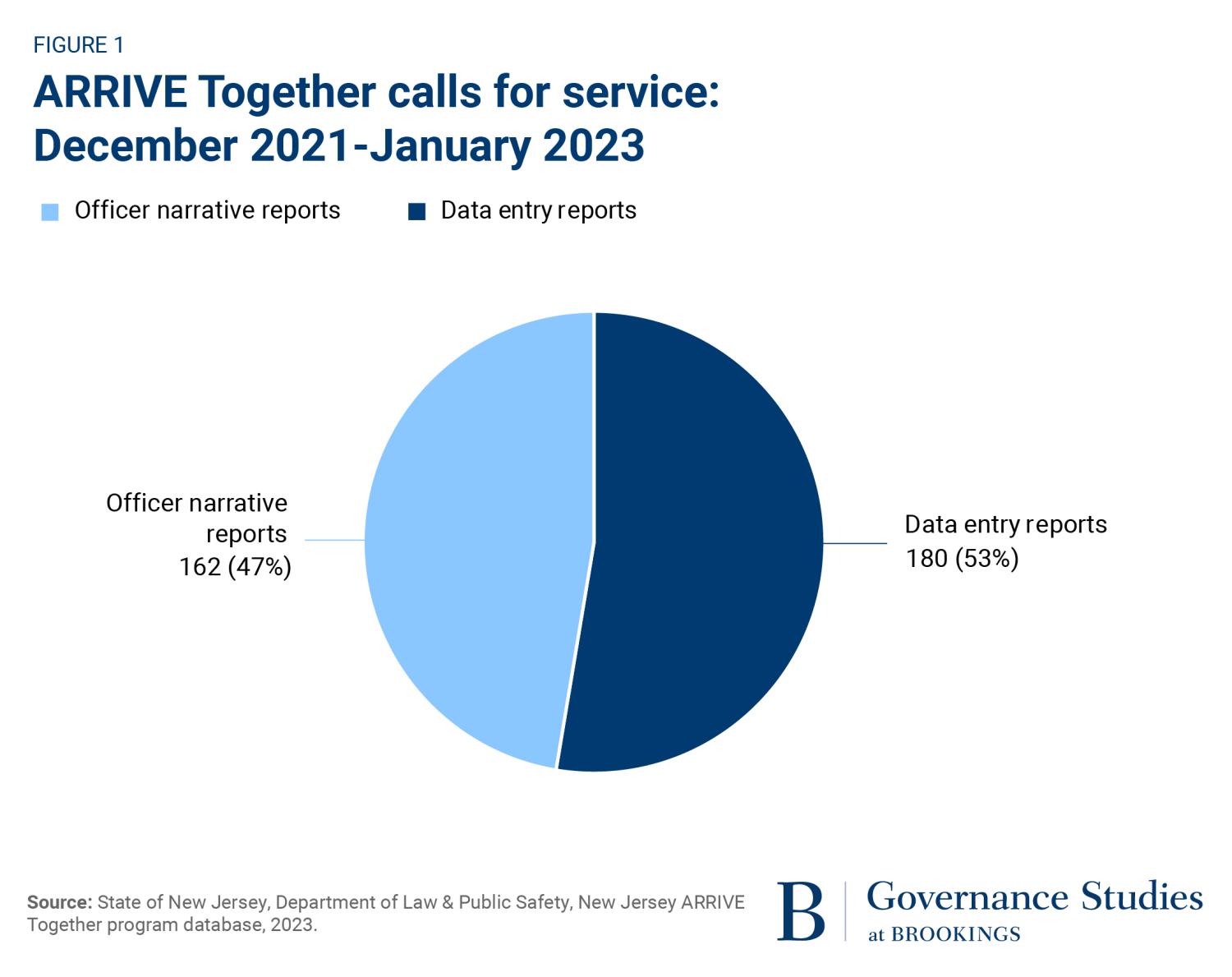

I analyzed a total of 342 cases which was comprised of 180 calls for service and follow-ups that were in data inputted files (quantitative data) and 162 calls for service and follow-ups that were distilled versions of short reports from police officers (qualitative data). The quantitative data ranged from June-December 2022, while the qualitative data spanned December 2021-January 2023.

ARRIVE Together shifts were held two times per week on days alternating between each police department. When not responding to reactive calls, the ARRIVE team followed up with previous individuals served as well as proactively visited individuals in the community known to law enforcement that would benefit from mental health services outreach.

The quantitative data included calls for service details and demographic information of the person of interest. The data for calls for service included the following variables: date of call for service, dispatch time, arrival time of ARRIVE team, end of service time, additional unit responses, arrival time of additional units, transport of person in question, arrest, and charges for arrest. The data also included demographic information of the person of interest including the following variables: race, ethnicity, gender, and age. The data files also included the incident type and any notes about the mental health of the person of interest.

For the qualitative data, demographic information was not directly reported. However, the age, gender, and location of the incident were at times mentioned as background and context for the call for service or follow-up. The qualitative data file also provided a snapshot of the data by summarizing the number of calls for service, eight-hour pilot shifts performed by the ARRIVE program, number of follow-up visits and proactive outreach contact, number of individuals served in response to calls for service or follow-ups, number of times that the mental health specialist made transport referrals, and number of times force was used. Whether an arrest occurred during the call for service or follow-up was detailed in the narrative reports. Overall, these reports provide important context to how the ARRIVE team makes decisions about how to address the call for service.

Analysis

The quantitative data were assembled in batches as files were received after being de-identified. The data files were examined for accuracy and completeness. The data were then transformed for quantitative data analysis. So, words were replaced with numbers to prepare for coding and analysis. The files were also checked for any overlap. Calls for service or follow-ups that were repeated across data files were deleted. This occurred if multiple departments responded to the same call for service. Next, the files were checked to ensure similarity among the variables. Finally, the files were integrated into one primary database. The primary database was imported into Stata, a statistical analysis software program, for further coding and analysis. The variables noted in the previous section were coded in Stata and then analyzed for any demographic differences in response times, type of call, use of force, and arrests.

The qualitative data included short reports from officers. The 162 calls for service and follow-ups were delivered in one secured word document. After reviewing all the calls for service reports, the descriptive data were reviewed for accuracy after an extensive coding process of counting the number of calls for service by date and calls for service reported. Next, the qualitative data were scanned for mentions of arrest, use of force, transport, and mental health type. Then, the data were coded for key themes of how mental health professionals and officers used discretion to make decisions about the outcomes of these calls for service. After establishing patterns in the coding, I searched the reports thoroughly again looking for examples that both confirmed and contradicted emerging patterns. Finally, my analysis cross-checked the reported numbers and themes to further verify accuracy.

Results

Quantitative Findings

This analysis aimed to examine whether law enforcement teams that pair mental health professionals with police lead to a lower level of arrest and use of force, higher utilization of mental health services as well as fewer racial disparities in these outcomes. Before diving directly into those results, I want to provide an overview of all 180 calls for service and follow-ups from the quantitative data files.

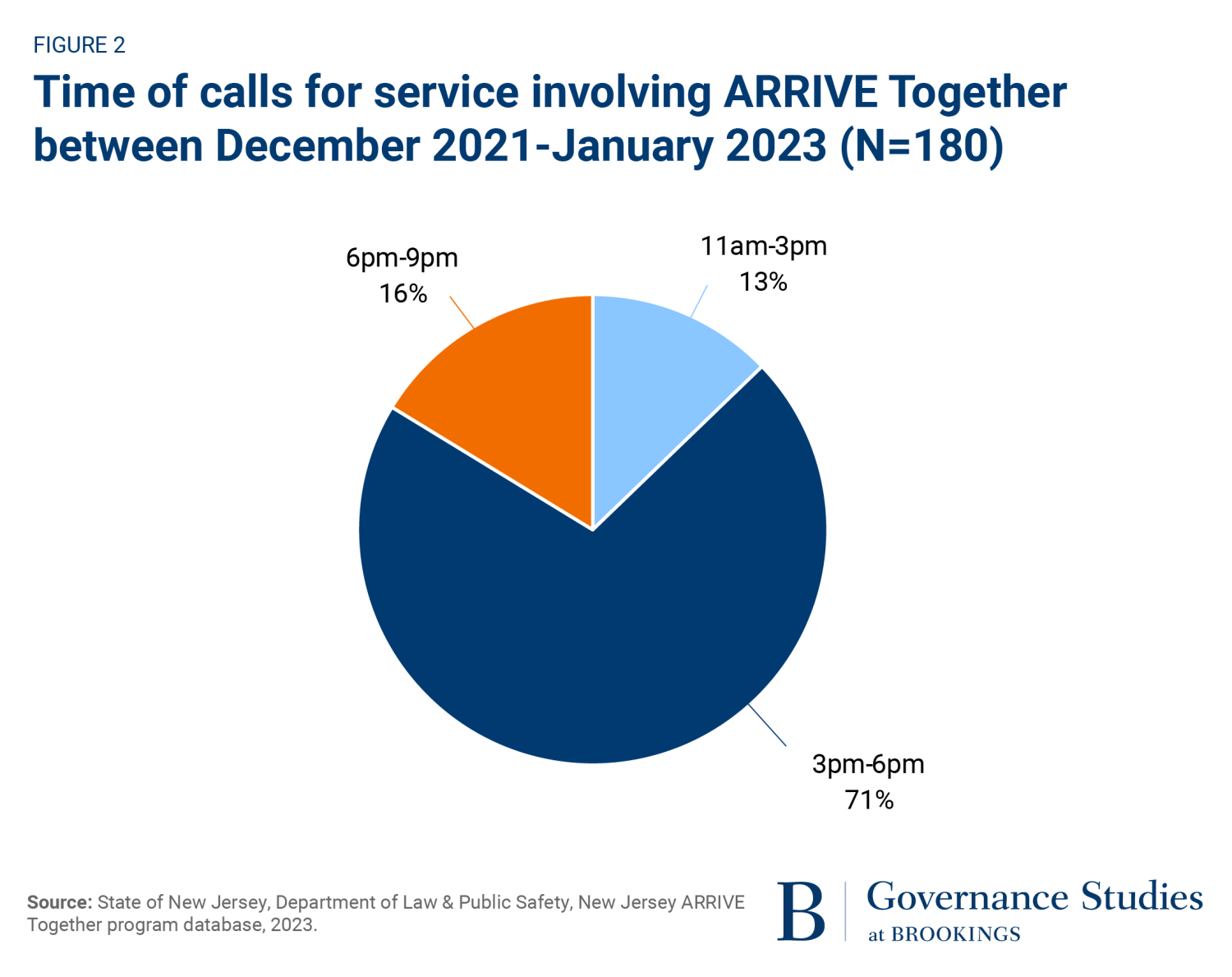

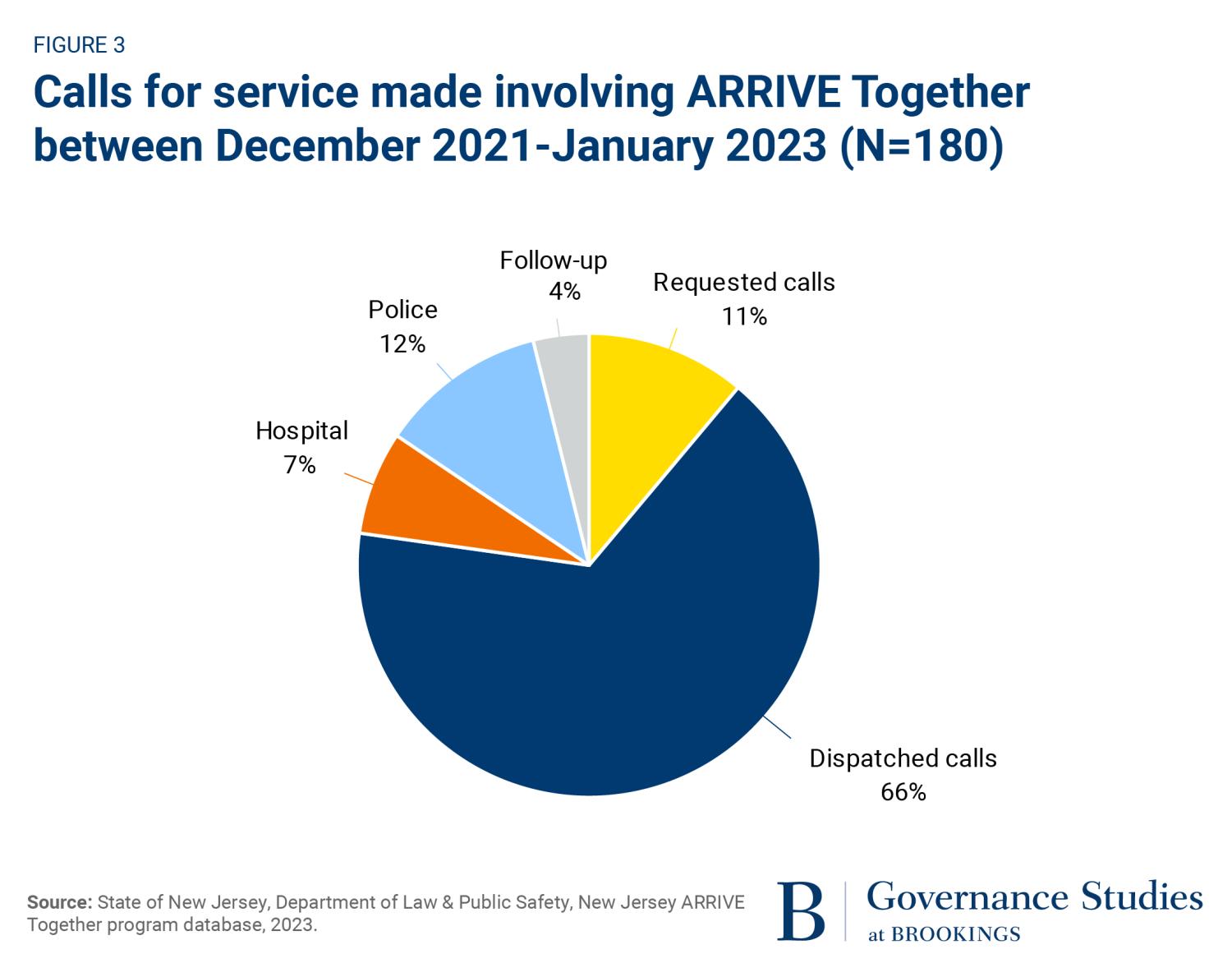

The ARRIVE teams responded to calls for service primarily during the afternoon. From 11am-3pm, nearly 13% of calls for service were dispatched, 71% from 3pm-6pm, and 16.3% from 6pm-9pm. Sixty-six percent of calls were dispatched from the operator, while 11% of calls were requested calls by the caller. Seven percent of calls came from the hospital, 12% from other law enforcement, and 4% were classified as follow-ups.

The average age was 41 ranging from 18 to 78. Sixty-three percent of the 180 calls were about men, while 37% were about women.

Table 1. Person of interest demographics

| Average age | 41 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 63% |

| Female | 37% |

| Race | |

| White non-Hispanic | 26% |

| Black non-Hispanic | 39% |

| Hispanic | 35% |

| White (including Hispanic) | 59% |

| Black (including Hispanic) | 41% |

Source: State of New Jersey, Department of Law & Public Safety, New Jersey ARRIVE Together program database, 2023.

“Existing research on policing suggests that officers misidentify the race and ethnicity of persons of interest. If identification is not present, officers may be relying on their judgment to identify people by race and ethnicity.”

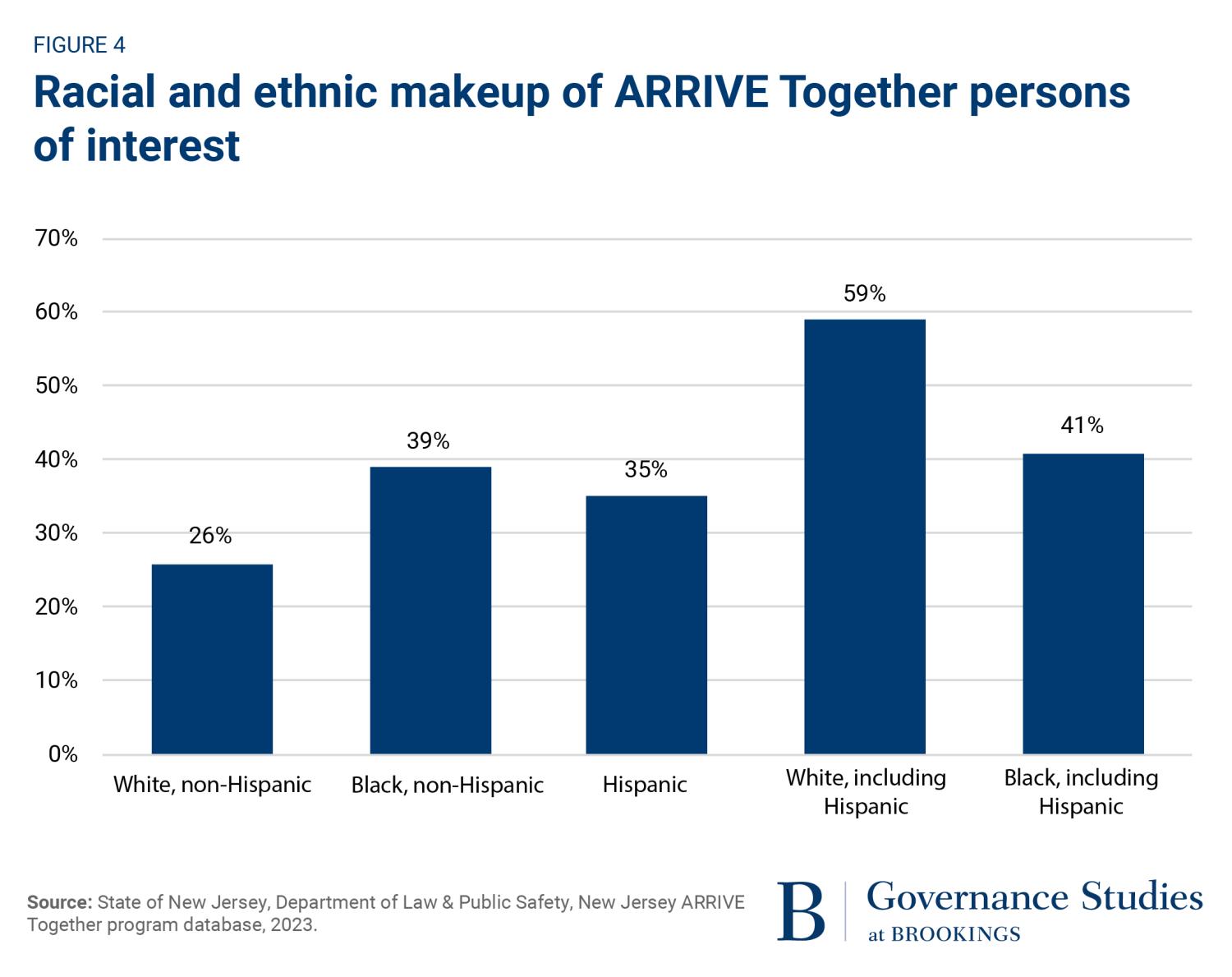

For race, 26% were identified as non-Hispanic white people, 39% as non-Hispanic Black people, and 35% as Hispanic people. While the percentage for Black people in the sample only increases to 41% when including Hispanic ethnicity, the calls for service about white people increased to 59% when including whether a white person was identified as also being Hispanic. Existing research on policing suggests that officers misidentify the race and ethnicity of persons of interest. If identification is not present, officers may be relying on their judgment to identify people by race and ethnicity. I speak to a policy solution to address this issue in the Recommendations section.

Of all 180 calls in the quantitative data reporting, zero calls ended in an arrest by the ARRIVE teams. Slightly over 16% of calls for service reported that a person was transported to a mental health facility or hospital. However, the notes reveal a higher percentage, indicating that EMS and law enforcement on the scene may have transported the person to a hospital or another location. The analysis also revealed no significant differences by the race, gender, or age of the person of interest when it comes to arrival time, requested/dispatching of the ARRIVE team, reporting agency, arrest, or use of force.

Concerning the reason for the call for service or follow-up, notes from the 180 cases revealed a range of incidents including: suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, drug overdose, failure to take medication, schizophrenia, bipolar, hallucinations, paranoia, depression, PTSD, dementia, autism, welfare checks, alcohol abuse, unhoused issues, domestic violence, threats to employees in various settings, alleged physical violence, and emotional outbursts.

“ARRIVE gives law enforcement more alternatives to provide people with the appropriate services and resources.”

One incident occurred at an elected official’s office resulted in the ARRIVE team following up at the man’s home later in the day. The man fled the public office and was later reported at his home for displaying erratic behavior. This case is interesting because it highlights the importance of ARRIVE to try and defuse situations. Without ARRIVE, officers may have had few options besides arrest. In fact, in several of the calls for service, the person of interest may have been arrested because the officers had few options. ARRIVE gives law enforcement more alternatives to provide people with the appropriate services and resources.

Qualitative Findings

The analysis of police officer reports reveals that mental health specialists on the ARRIVE Together teams help officers de-escalate situations, reduce force and arrests, and provide additional options to assist community members to identify and utilize social services. Of the 68 calls for service and 94 follow-up visits and proactive outreach contacts, ARRIVE assisted over 160 people. The age of people assisted ranged from 13 to 91. Fifteen of these individuals were voluntarily or involuntarily transported to a hospital or mental health facility. Not including the incidents using transport noted above, force was used in four incidents and seven calls for service resulted in an arrest. Of the seven arrests, three people had an outstanding warrant, one person was shoplifting, two were arrested for domestic violence (including a woman who hit her husband in the head with a hammer), and one was an autistic teenager who was arrested for being “combative.” Collectively, among all 342 calls for service and follow-ups pertaining to the ARRIVE Together program, only 2% had an arrest occur.

“Collectively, among all 342 calls for service and follow-ups pertaining to the ARRIVE Together program, only 2% had an arrest occur.”

In the case of the autistic teenager, a student reported to a school principal that a friend sent a text message stating that he was going to kill himself. The ARRIVE team went to the teenager’s home and after performing a suicide assessment, the mental health specialist determined that the teenager should undergo a full crisis evaluation at a facility. The teenager did not want to be detained and was handcuffed by an officer and then transported to a facility.

It is clear from the reports that officers probably had the legal authority to arrest a higher number of people than the seven that were ultimately handcuffed. However, the presence of the mental health specialist gave officers additional options to assist community members with mental health issues. There were incidents where guns and other weapons were present. However, ARRIVE staff were often able to diffuse situations with crisis intervention techniques. In these situations, officers often elected not to arrest individuals or even bring them to the station for additional questioning, and instead allowed them to be immediately transported to a medical facility or have a follow-up by the ARRIVE team in the coming days.

For example, ARRIVE was dispatched to a group home where two residents were fighting. Clothes were ripped, furniture was tossed, and both individuals involved had scratches. Though the two individuals refused medical treatment, ARRIVE staff were able to de-escalate the situation and no further action was taken by law enforcement. In another incident, a son called the police on his father for allegedly pulling a gun on him. Upon arrival, officers found weapons in the home. Due to the father’s Alzheimer’s and dementia, officers decided to bring both men to the station and have ARRIVE evaluate them for suicide ideation. After a consultation and the offering of resources (though the father refused), the men were cleared of any suicide ideation.

“Findings also show that the presence of the ARRIVE team helps to diffuse situations.”

Findings also show that the presence of the ARRIVE team helps to diffuse situations. For example, police officers arrived on the scene to deal with a woman with a history of mental illness. The woman reported discomfort in the presence of police. Because a mental health specialist was present, the officer left the room. The woman was ultimately involuntary transported back to the hospital, though she did not want to go. The incident may have escalated further if the mental health specialist had not been there.

In another call for service, ARRIVE responded to a wellness check for a teenager with a knife threatening to kill herself and others. When they arrived at the home, the ARRIVE team determined that the girl was in a physical altercation with two friends who live at the same residence. A knife was not found at the scene. As a result, ARRIVE had the teenager transported to spend the night at her grandmother’s home. The ARRIVE team later followed up on this incident and classified the situation as “stable.”

The data also revealed that ARRIVE helps officers engage in behaviors that often go undervalued or unnoticed in the caring of community members. While performing a wellness check, it was a determined that a woman broke her phone and did not have a way of communicating with people. The officer traveled to a local post office to retrieve the woman’s new phone and the mental health specialist helped set up the phone. During that time, the officer also helped fix the woman’s toilet.

Additionally, ARRIVE helps with cumbersome bureaucratic processes. ARRIVE staff often met persons of interest at the police station for crisis evaluation rather than at the hospital. A law enforcement captain stated that before ARRIVE, an officer would have taken the individual to the hospital. Transferring individuals from law enforcement to the hospital to mental health services often causes significant delays in care and treatment, while also wasting time and resources (including the possibility of the person of interest having to cover medical costs). In one incident, ARRIVE was called to the police station to evaluate a person alleging identity theft. ARRIVE staff provided the appropriate resources. As a sign of gratitude, the person wrote a poem for the ARRIVE staff member.

Recommendations

This analysis has yielded a series of recommendations that can be useful for a program such as ARRIVE to improve and thrive moving forward. Below is a list of recommendations to ensure the ARRIVE Together program can be an exemplar for other states and localities.

- ARRIVE Together and similar programs need to have a detailed coding scheme to track which type of mental health/mental illness symptoms and diagnoses are being reported. I listed a series of reported mental health issues in the findings section. It is ideal to be able to perform analysis to determine if certain individuals may be more likely to experience certain types of mental health issues. It may also be determined that certain staff members are better at responding to certain types of calls for service based on the mental health symptoms being reported.

- It is imperative for the data collection and reporting to be complete and synchronized across jurisdictions to ensure validity and reliability. I did not have complete and detailed information on important variables regarding the specifics of arrests and which additional supports were called to the scene. The lack of complete demographic data can actually weaken the case of just how effective the program is at reducing, and in some cases, eradicating racial disparities in policing outcomes. For example, I did not find differences in response time based on the race of the person of interest. This is important considering existing research shows that first responders often take more time to arrive when the caller and/or person of interest is Black. Detailed information about additional responding units and who makes an arrest or uses force will be useful moving forward.

- It is important for ARRIVE team members to describe how they use discretion and how their subjective judgements and behaviors may reduce their likelihood of using force or arresting someone. This shift in reporting is critical to changing an over-reliance on negative outcomes in policing and, instead, highlights the positive ways that ARRIVE team members are using discretion to improve lives. This shift in reporting will also allow law enforcement to improve police-community relations and develop more trust within marginalized communities.

- Law enforcement needs to improve how race/ethnicity is identified. As mentioned in the quantitative findings section, the difference between whites identified as white non-Hispanic versus white is significant. It could be an important policy shift to start asking people their race and ethnicity rather than relying on officer perceptions that may be inaccurate. This policy change would not only show where racial/ethnic disparities may be present, but in the case of this study, to show that racial/ethnic differences do not exist.

- It is important for an analysis such as this one to include the demographics of the ARRIVE team. Research is conflicted about whether the race and/or gender of officers matter. from the Lab for Applied Social Science Research shows that the race and gender of officers does not matter as much as previously thought regarding use of force incidents. Other research out of Chicago suggests that Black officers and female officers are less likely to use force, especially when they live in or around the area. Research in healthcare documents the importance of race and gender concordance in healthcare provider/patient encounters to increase trust. Altogether, ARRIVE Together has a unique opportunity to speak to both areas. Considering this study did not find racial differences among persons of interest, and the number of arrests and use of force were low, it is plausible that the demographics of ARRIVE Together staff would show few differences, if any, regarding treatment. A state as diverse as New Jersey has an important role to play in this broader debate about diversity.

- There must be comparisons to non-ARRIVE Together calls for service. This comparison will allow for an examination of whether officers who either volunteer or are selected for the ARRIVE Together Program are unique in terms of training, background, empathy, or understanding of the individuals dealing with mental health issues. This comparison will also speak to the culture of New Jersey police departments. In recent years, some New Jersey departments have made considerable changes in efforts to improve the structure and culture of their police departments. ARRIVE Together may be an additional vehicle to showcase these changes. Or, ARRIVE Together may be that unique and components of the program may be expanded to other areas within law enforcement.

- Different configurations of law enforcement mental health response teams are popping up across the country. It is vital to compare these different models to determine which cofigurations might best serve individuals dealing with mental health issues and why. It is clear that ARRIVE Together is one of the programs doing an important service.

- State-level oversight can be important to ensure synchronization of information and sharing of best practices as well as the elimination of problematic processes. State-level oversight can also ensure that ARRIVE Together personnel across the state meet regularly to ensure continuity and similar interactions with the public.

Conclusion

This report aimed to determine whether a police response team that includes officers and mental health professionals lead to less use of force, fewer arrests, less racial disparities, and more people receiving mental health services. After my analysis of the New Jersey ARRIVE Together program, the pilot data suggest much promise.

Of the 342 calls for service and follow-ups analyzed in this report, force was used in about 3% of calls for service. Only seven ended with an arrest. This means 98% of calls for service and follow-ups involving the ARRIVE Together program did not lead to an arrest. Given the reasons for the arrests, it can be assumed that the ARRIVE teams did not necessarily contribute to a majority of them.

Altogether, it is clear that ARRIVE Together is a highly effective program for reducing arrests and use of force (even across racial groups and other demographic outcomes), providing people experiencing mental health symptoms with specialized services, and reducing the workload and lack of specialized training among law enforcement so they can direct resources to address violent crime and other criminal activity. ARRIVE has the potential to and may already be improving police-community relations and restore trust in law enforcement.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).