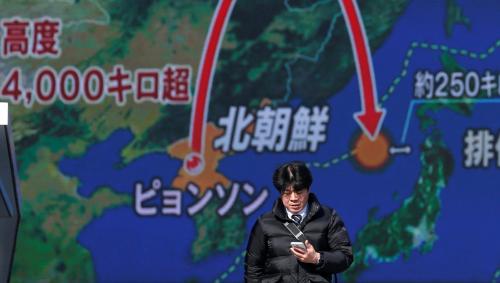

How do publics in East Asia view the threats emanating from North Korea, and how do they view possible military options in response? These and related questions were the topic of a recent event we hosted at Brookings, along with Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow Shibley Telhami and Yasushi Kudo, president of The Genron NPO, a Japanese polling firm. As our colleague Shibley writes in a new blog post, the University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll, in partnership with Tokyo-based The Genron NPO, compares Japanese and American public opinion on North Korea and Asian security broadly.

Richard Bush on South Korean opinions

Bush argued, first of all, that Koreans have the most at stake in this crisis. As Brookings scholar Jonathan Pollack is fond of noting, it is the Korean Peninsula we are talking about, after all. In particular, there is a widespread assumption that overly aggressive action against North Korea by either the United States or the Republic of Korea would lead to unacceptable retaliation by Pyongyang against the South. Since South Korea is on the front lines, South Korean views have a presumptive value.

Second, South Korean political trends have changed more than Japanese or American ones with regards to the North Korea issue. The South had conservative presidents for nine years, and then all of a sudden now have a progressive president. President Moon Jae-in is pursuing an approach toward North Korea that, compared with his two conservative predecessors, is more conciliatory, based on engagement and dialogue. That raises the question of whether public attitudes among South Koreans have moved as well.

Two other polls help us answer that question: one by Gallup Korea last September, and the other by The Genron NPO last July. They didn’t ask the same questions, but that’s okay—the findings still illuminate some important sentiments.

Gallup Korea Poll – September 2017

These responses indicate that South Korea holds no illusions about the danger their country faces.

For a rather simplistic question, Bush said, this set of responses strikes him as a good reflection of what he understands South Korean views to be.

Note that the Genron NPO asked a similar question of South Korean respondents, but in a different and more open-ended way: That question asks not whether North Korea will start a war, but whether military action will occur in response to North Koreas’s nuclear weapons development:

For 39 percent of South Koreans to say yes is not that different from Gallup, where 13 percent said there was a high possibility that North Korea would start a war, and 24 percent said there was a slight possibility.

Bush noted that for 33 percent to agree is higher than he expected, but it’s suspiciously close to the working estimate for the strength of conservative voters (with another 33 percent progressive and another third in the middle). So, the answer may reflect basic ideology more than a policy preference.

The “yes” response seems high, Bush said, but his recollection is that previous polls have gotten similar results. One possibility is that conservative and swing voters—who believe their country should go nuclear—are driving up that number.

That is, 47.9 percent of South Koreans favor some kind of diplomacy with the North.

On the longer-term future, The Genron NPO asked South Korean respondents what the Korean Peninsula would look like 10 years from now: 29.2 percent said the status quo will persist, 31.2 percent said the North-South conflict will intensify, and only 19 percent said the two will move to reunification. 20.1 percent said it’s unpredictable. To Bush, that seemed like a pretty realistic distribution of predictions.

What we have, therefore, is a mixed picture in Korean opinion: The public appears to think that North Korea is a threat but war is not likely; that diplomacy is the method for addressing the current impasse but also that South Korea should go nuclear; and that the future will look about the same or worse than today.

Michael O’Hanlon on the (bad) military options

O’Hanlon’s comments focused more on what kinds of military options the United States (and perhaps South Korea, though that seems less likely) might be contemplating. He laid out four different concepts and assessed the respective merits of each—ultimately concluding that none were good ideas, because each promised only limited benefit yet a substantial risk of North Korean response and escalation. The options he presented, and his assessment of each, were as follows:

1Shoot down long-range missile launches. One military option would be to prevent North Korea from completing any more long-range missile tests to perfect ICBM technology. This idea was proposed in 2006 by two Democratic secretaries of defense, William Perry and Ashton Carter, though it is not clear either of them would still support it today. The missiles could be destroyed by precision munitions launched from aircraft just before launch. Or they could be shot down in flight by a U.S. missile defense system; based on previous testing, any such shot might have a 25 to 75 percent chance of success.

However, in response, North Korea might accelerate its development of solid-fueled intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), which have a launch preparation process that is difficult to detect. The United States might not shoot down such ICBMs effectively in peacetime or in war.

Furthermore, this idea does not address North Korea’s growing inventory of perhaps several dozen nuclear warheads (and shorter-range missiles that could carry them) that already put Seoul and Tokyo at risk, including the hundreds of thousands of Americans living there.

2Blockade North Korean ports. To the credit of the Trump administration, the U.N. Security Council has just imposed additional sanctions on the DPRK. These would, among other things, reduce certain types of fuel imports up to 90 percent and severely squeeze the remittances sent home by North Korean workers living in places like Russia.

A blockade by the United States and allied navies could seem a logical way to ensure that such sanctions were actually respected. Of course, a military blockade is, by standard international law, an act of war. Enforcing it could require the use of lethal ordnance against any North Korean or other ships that refused to allow boarding and inspection. In response to such a blockade, North Korea could be expected, at a minimum, to shoot at any nearby ships that were targeting its own vessels, risking American casualties.

Even more importantly, this option would not curtail trade across North Korean land borders or airspace. Thus, it would neither reduce the existing threat posed by North Korea, nor likely slow further growth of nuclear and missile arsenals in the future. It would tighten the economic squeeze, but fail to reduce the military threat.

3Destroy North Korean nuclear infrastructure. Just as Israel preemptively attacked Iraqi and Syrian nuclear reactors in 1981 and 2007, the United States and/or South Korea could take aim at parts of North Korea’s nuclear infrastructure, most likely with stealthy attack aircraft. Specifically, the nuclear reactor that is under construction but not yet operational could be destroyed without dispersal of highly radioactive material, as could the uranium centrifuge complex at that same site.

Unfortunately, such preventive strikes could not eliminate any second uranium enrichment facility that North Korea may have built at an unknown site. Nor could they humanely destroy the operational research reactor that has produced all of North Korea’s plutonium to date. An attack on such a site would create a miniature Chernobyl or Fukushima-like outcome, lethally spreading highly radioactive reactor waste over an area of hundreds of square miles downwind. Such an attack would be unlikely to reach any of the several dozen warheads North Korea already likely possesses, since U.S. officials do not know where they are located.

4Target Kim Jong-un directly. Like the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, when the Bush administration attempted to kill Saddam Hussein in an early “shock and awe” strike, the United States and South Korea could target Kim Jong-un. U.S. law prohibits assassinating foreign political leaders. But if Kim were declared the military commander of a nation still technically at war with the United Nations and in violation of its cease-fire obligations (due to frequent repeated aggressions against South Korea over the years), this issue might be finessed, at least legalistically.

However, the United States might miss Kim Jong-un in any such attempt, as the 2003 Iraqi case demonstrates. Whether successful or not, North Korea might respond with similar attempts against Western leaders.

And where would even a successful operation get the United States? Unless U.S. officials were able to message virtually all other senior North Korean leaders in advance, and persuade them to accept amnesty and exile if they chose not to resist, killing Kim Jong-un might just lead to the replacement of one extremist leader with another. North Korean military command and control might also splinter, with some elements opting for a violent response against the United States and ROK rather than for surrender.

In short, O’Hanlon concluded, whatever their individual appeal, each of these options would appear to promise only mediocre effects against the North Korean threats that matter most to the United States. O’Hanlon expressed the hope that the Trump administration understands as much, and that it is using its threats of military action to create a sense of urgency about the need for North Korean concessions rather than to signal looming attack.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Navigating options on North Korea

January 22, 2018