Just turn on the TV or flip through a magazine and you will recognize a keen interest in millennials that shines a light on their distinct lifestyles, preferences, and career aspirations. Much of the information about this roughly age 22-37 cohort is generated by the business sector as it designs and markets new products to capture their interest and create work spaces to keep them happy and productive. On the other hand, the education sector has been slow to follow this lead in its effort to recruit, groom, and retain a subset of this cohort: highly sought PK-12 millennial teachers of color.

This May, Harvard Education Press published “Millennial Teachers of Color,” a book that addresses a missing link in the recurrent conversation about teacher diversity. Though the new teachers we are trying to recruit are racially and ethnically diverse, we often overlook that they are also part of the millennial generation—the most diverse, educated, socially connected, and now largest generation in the workforce. They come to the classroom with perspectives and attitudes about education that have been shaped not simply by race or ethnicity, but by all of these characteristics. Yet, too often, these diverse perspectives go unnoticed and even dismissed, and schools miss an opportunity to improve their culture in ways that could benefit teachers and students.

As editor of this volume, I gathered research and insights about these new young teachers of color from millennial, Generation X and baby boomer contributors. Collectively, they offer lessons on how we can create stronger engagements with these new entrants into the profession to further the common goal of quality teaching and learning for all students. Here are some of the insights worth considering.

Millennials as agents of change

Although “generalizing about generations can be messy,” there are a fair number of characteristics assigned to the millennial cohort that are indisputable. They are the largest and most racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse generation to date, and in 2015 surpassed Generation X to become the largest share of our nation’s workforce. They tend to have strong opinions about education as a mechanism for social justice and are engaged by issues more so than by political parties. Advantaged by technology, they have many more options than their predecessors to express their feelings and views. Generally speaking, they are primed and equipped to disrupt the status quo in society often in surprisingly powerful ways.

Remember this past April’s racially charged incident in a Philadelphia Starbucks café? Starbucks is the coffee venue of choice for a large proportion of millennials, but in a few short minutes of text messaging and with a posted video, millennials of color disrupted and prodded a solid, decades-old enterprise to immediate change. Starbucks closed its huge operation for a costly four hours of training to better acquaint its employees with issues of implicit racial bias and made a firm commitment to restructure its approach to serving all of its customers better.

As members of this millennial generation, teachers of color who now enter and remain in the classroom—even for a few years—also think a lot about large-scale change in teaching and learning. They arrive in schools with tremendous energy and a desire to effect change. To this point, however, their effects on public school systems and training programs have been fairly subtle.

Muffling change

Diversity-oriented recruitment initiatives lead millennials of color to believe that they are particularly valuable to the teaching and learning enterprise, but once employed their experiences are underwhelming and they frequently move to different fields in search of higher ground. This message is conveyed clearly by millennial teachers Sarah Ishmael, Adam Kuranishi, Genesis Chavez, and Lindsay Miller in Chapter 1. Economic disparities and racial injustices are the unspoken condition of their jobs, but often they are the only ones willing to speak openly about causes and consequences for the benefit of their students.

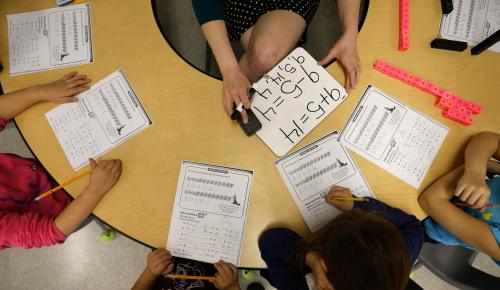

Teachers of color are known to make great strides in leveraging the academic performance of all students, and underachieving students of color in particular. Drawing from their own experiences as they grew up in these diverse communities, they have authentic notions of cultural responsiveness—instruction delivered in ways that work best for their students to survive and thrive as adults. Yet, the harsh reality described by Sabrina Hope King in Chapter 7 is that entrenched processes and procedures constrain these educators and leaders and provide no time, resources, or outlets to hone their cultural knowledge and skills into viable alternatives to current practice.

The teaching and teacher education sector has already begun to feel the consequences of essentially ignoring them to maintain the status quo. Aside from disappointing attrition rates among teachers of color, there are other indicators of discontent. For example, there is a clear and deliberate move away from old-style initial preparation programs to those that appear to offer more active and abbreviated training, and a preference for continuing professional development entities that typically operate outside of colleges and universities. And they gravitate toward public and charter schools (both independent charters and those run by larger networks) that, in theory, offer greater degrees of freedom to hone their culturally responsive skills and knowledge. As Lisa Delpit writes in the Foreword, “The ‘browning’ of the millennials makes it imperative that we develop an understanding of how these complex young people navigate the world, and that we make explicit how the challenges and the gifts of millennial teachers will change the face of education as we know it.”

‘A change is gonna come’

Advantaged by technology, millennial teachers have more options than their predecessors to exhibit their feelings and connect with others through alternative means. Those teachers of color who remain in the profession often organize their thoughts and action plans below the radar in a virtual space and in a language that sometimes seems foreign to their baby boomer and Generation X colleagues and relations. As Keith Catone and Dulari Tahbildar note in Chapter 5, “As motivated as many millennials are for activism and social justice, it is not clear that the field of education currently has the systems and infrastructure necessary to cultivate, celebrate and commit to this new teaching talent.”

Thus, teachers of color are often compelled to seek community outside of their brick-and-mortar schools. Hollee Freeman in Chapter 4 describes a number of millennial teachers of color who are skillfully finding ways to negotiate the system in an attempt to establish teaching and learning communities, either virtually or in person, that reflect meaningful change. The hope is that these out-of-school communities will provide an outlet for productive engagement and learning opportunities that can eventually be transferred back into schools to have a positive impact on students and colleagues.

We need to allow these change-makers to speak up for the good of all students, and we should listen when they do. If and when these young teachers of color find a genuinely welcoming environment within schools to offer new ideas and are authorized to groom the best ones, they will be more inclined to stay. If they find an unwillingness to see beyond the existing state of affairs, they will no doubt leave the profession sooner than later. Partnerships of local PK-12 school district administrators, school boards, early-career millennial teachers of color, and community groups may provide an ideal test bed where a mission-driven team of professionals work together to strengthen our school cultures.

As the nation’s student population becomes increasingly racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse, the goal to provide a quality education for all children hinges in large measure on the work of millennial teachers of color. We need to create a real space for them if real change is to be possible in public schools.

Commentary

Millennial teachers of color will change public schools—if given the chance

August 24, 2018