Who would Americans trust to best understand the broadband-related interests of the residents of a city: its mayor, or the head of the Federal Communications Commission?

This is not just a theoretical debate. The mayor of San Jose, Calif., Sam Liccardo, and the FCC commissioner, Brendan Carr, have recently engaged in a heated debate over upgrading the city’s broadband service. In many ways, the situation in San Jose looks like much of America. Mayor Liccardo grew up in San Jose, worked there as a prosecutor, served on the City Council from 2005 to 2015, was elected mayor in 2015, and was just re-elected with 75 percent of the vote. With about twice as many Americans having a positive view of their local government than they do the federal government, it’s a near certainty that most city residents would trust Mayor Liccardo’s team to better determine broadband equity deployment issues than Commissioner Carr and his team inside the Beltway.

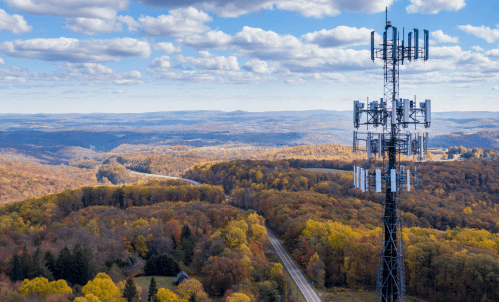

The development of new digital telecommunications capabilities combined with a persistent digital divide leaves the public sector with enormous responsibilities to promote network quality and deliver equitable access—but it can only do so by sensibly splitting regulatory responsibilities between the national and local levels. Unfortunately, news out of Washington, D.C. reveals the federal government has overstepped its appropriate role, constricting local governments’ abilities to craft locally tailored solutions.

The commissioner, however, doesn’t see it that way. He engaged in a Twitter war with the mayor and penned a San Jose Mercury op-ed arguing that his proposal for the deployment of 5G mobile networks is better for San Jose than the mayor’s.

So, who’s right? Let’s compare their actual approaches.

The mayor negotiated deals with Verizon and AT&T that commit all sides to actions that assist carriers deploying network facilities, provide benefits to all related Internet of Things applications, and support the city’s efforts to narrow the digital divide and invest in more efficient administration.

By contrast, the commissioner pushed the FCC to adopt an order to preempt local government authorities around where and how quickly broadband providers could install 5G small cell towers. The order raises the costs for cities, forcing them to allocate new resources to meet federal timetables for a single, favored form of construction. It even regulates the price that cities can charge for accessing city property, taking money from cities and transferring it to carriers.

What did the commissioner ask from the carriers? Nothing. In exchange for price reductions on existing uses of the cities’ property—a gift estimated to be worth $2 billion nationwide—the carriers have no obligation to do anything.

Commissioner Carr’s arguments in his op-ed were unlikely to persuade San Jose residents of the benefits of his approach. He asserts that if carriers save money building networks in San Jose, they will spend it by deploying networks elsewhere, thereby accelerating availability of 5G services throughout the country. It’s a curious argument. Why should San Jose residents care or be forced to subsidize network construction outside their city?

But even from a national perspective, Commissioner Carr’s arguments are factually flawed. Market signals confirm the FCC order won’t lead to accelerated investment. As the CFO of Verizon said on a call with investors, “I don’t see it [the FCC’s order] having a material impact to our build out plans. We are [already] going as fast as we can.” Further, since the FCC order, the wireless industry has actually reduced its plans for capital investment. As additional evidence of the flaws in the FCC’s order, it provided no data or explanation to explain why a carrier would prioritize the use of its savings any different than it uses any other additional money. That is, the money is more likely to be used for purposes such as stock buy backs, dividend support, or deleveraging than new capital investments.

Even from a national perspective, Commissioner Carr’s arguments are factually flawed. Market signals confirm the FCC order won’t lead to accelerated investment.

It sure seems like the mayor’s approach protects the interests of local residents and businesses more than the FCC. And that’s certainly how most cities across the country read the situation.

A number of cities are suing the FCC, testing, among other things, whether the FCC can take one city’s money on the hypothetical grounds it will help another city. Regardless of the outcome of the litigation, however, the battle between the mayor and the commissioner is a warning sign in the emerging debate over regulation of our information economy.

When it comes to policies affecting internet networks and applications, some argue that under the interstate commerce clause and related federal statutes, only the federal government should have authority to act. Indeed, industry is making that argument in the case of 5G deployments and on other issues, such as net neutrality and privacy.

The argument is not frivolous. Some pieces in the communications infrastructure puzzle, like spectrum, require national answers; radio signals don’t stop at state and local borders. Some issues, like privacy and other consumer protections, have historically been subject to dual state and federal jurisdiction.

But construction management involving municipal rights of ways? Certainly, the FCC could play a constructive role in bringing industry and municipalities together to find ways to reduce costs for both sides or undertaking data-driven analysis and evangelizing about city policies that accelerate deployment.

“One size fits all” federal rules governing the use of local property, however, is over the line. Current FCC decisions suggest the commissioner cares little about what cities think and the FCC’s leadership is out of touch with economic reality and local interests. As a result, I expect more litigation between the FCC and cities. And no matter what the courts decide, that ongoing litigation will divert resources and attention away from efforts, like bridging the digital divide, that require local authorities, federal officials, and private sector partners working together to develop common sense solutions that actually serve local communities.

Nor is the issue of who decides what is limited to this issue. The deepest philosophical and historic foundations of the United States represent the efforts of our Founding Fathers to implement John Locke’s insight that the legitimacy of the government requires the consent of the governed. Over the next decades, we will struggle with a number of issues such as climate change, artificial intelligence, bio-engineering, and others that arguably require international solutions. The answer to what constitutes the consent of the governed in a global, information economy will not be delivered in a single answer and may take decades and many trials and errors before there is an agreed upon approach that is both effective and respects local, national, and international interests.

Americans would be right in trusting mayors more than federal officials.

When it comes to the core political decision of who decides the rules for using local assets to build infrastructure, however, the answers are easier. Americans would be right in trusting mayors more than federal officials. Mayors, after all, are answerable to local citizens far more than a far-off federal official, and they have obtained the consent of the governed in a way the federal official has not. Further, different cities should be allowed to answer the question differently as that is the best, market-based way to determine the trade-offs of different approaches.

As the conservative political analyst Yuval Levin wrote in his book Fractured Nation, “The absence of easy answers is precisely a reason to empower a multiplicity of problem-solvers throughout our society, rather than hoping that one problem-solver in Washington gets it right.” In addressing policies affecting the internet, we have to find a way to honor the wisdom of distributed decision making and while protecting interstate commerce. The FCC failed. Let’s hope other government officials get the balance right.

Commentary

Mayors or the FCC: Who understands the broadband needs of metropolitan residents?

February 22, 2019