Many U.S. and European intelligence officials fear that a wave of terrorism will sweep over Europe and the United States, driven by the civil war in Syria and the crisis in Iraq. The terrorist attack in Paris, and in particular the apparent connection of the attackers to a terrorist group in Yemen, has sharpened these concerns. But despite these fears and the real danger that motivates them, the Syrian and Iraqi foreign fighter threat can easily be exaggerated.

Fears about foreign fighters were raised concerning many conflicts, especially after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq; yet for the most part, these conflicts did not produce a surge in terrorism in Europe or the United States. Indeed, in the case of Iraq in particular, returning foreign fighters proved much less of a terrorist threat than originally predicted by security services.

In our recent policy paper, we argue that previous cases and the information already emerging from Syria suggest several mitigating effects that reduce—but hardly eliminate—the potential terrorist threat from foreign fighters who have gone to Syria. These mitigating factors include:

- Many die, blowing themselves up in suicide attacks or perishing quickly in firefights with opposing forces.

- Many never return home, but continue fighting in the conflict zone or at the next battle for jihad.

- Many of those who go quickly become disillusioned, and even many of those who return often are not violent.

- Others are arrested or disrupted by intelligence services. Indeed, becoming a foreign fighter—particularly with today’s heavy use of social media—makes a terrorist far more likely to come to the attention of security services.

The danger posed by returning foreign fighters is real, but American and European security services have tools that they have successfully deployed in the past to mitigate the threat. These tools will have to be adapted to the new context in Syria and Iraq, but they will remain useful and effective. Experience thus far validates both perspectives on the nature of the threat.

Security officials are paid to worry about threats and foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria provide ample room for worry. Thousands of Sunni Muslims have gone to fight alongside their fellow Sunnis against the Syrian and Iraqi regimes. (Thousands more Shi’a have gone to fight on the side of those governments. But it is the Sunni foreign fighters from Europe and America, with passports that enable them to go anywhere in Europe or the United States without a visa, who worry Western officials.)

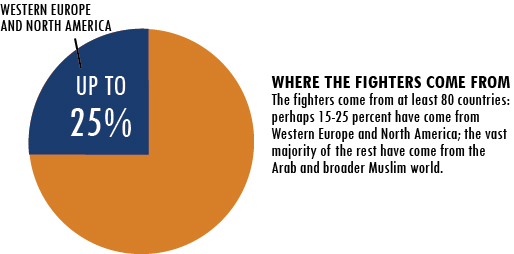

The overwhelming majority of foreign fighters who have gone abroad to join the fight in Syria and Iraq have come from the Arab world. But Western Europe’s sixteen million and America’s two million Muslims also feel the pull: the carnage in Syria, the refugee crisis, and the violence between religious communities there have echoed throughout the West. Satellite television and social media bring images of sorrow and slaughter into the homes of Western Muslims every day. All sides increasingly consider the conflict sectarian, pitting Iraq and Syria’s Sunnis against the Iraqi and Syrian regimes and their Shi’a supporters in Syria, Iraq, Iran, and elsewhere.

Western security services fear that the foreign fighter threat in Syria and Iraq is different in important ways than past foreign fighter problems. Young European and American Muslims will go off to fight in Syria and Iraq as Sunni idealists but will return as anti-Western terrorists. They see combat experience in the region as a double threat. Many of those who go to war will come back as hardened veterans, steady in the face of danger and skilled in the use of weapons and explosives—ideal terrorist recruiting material. While in the combat zone, they will form networks with other Western Muslims and establish ties to jihadists around the world, making them prone to further radicalization and giving them access to training, weapons, and other resources they might otherwise lack. This fear of violence is particularly acute because many of those going to Syria and Iraq are social misfits and “marginalized… juvenile delinquents. It’s often people who were criminals before,” according to French officials.

American officials have similar fears. FBI director James Comey stated that “All of us with a memory of the ’80s and ’90s saw the line drawn from Afghanistan in the ’80s and ’90s to Sept. 11.” He then warned: “We see Syria as that, but an order of magnitude worse in a couple of respects. Far more people going there. Far easier to travel to and back from. So, there’s going to be a diaspora out of Syria at some point and we are determined not to let lines be drawn from Syria today to a future 9/11.” Comey also explained that because the European Muslims are from countries whose citizens can travel to the United States without a visa, they are of greater concern, as they can more easily slip through U.S. security.

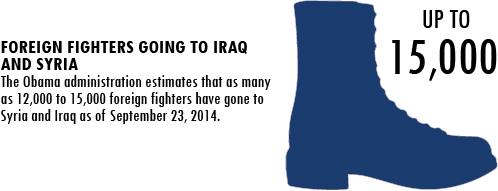

Most importantly, the foreign fighter problem in Iraq and Syria is simply bigger than past cases. Recent reports estimate that between 2,000 and 3,000 foreign fighters from Western countries have traveled to Syria and Iraq as of September 2014, including over 100 Americans; France, Britain, Belgium, and Germany have the largest numbers of citizens in the fight. However, these figures may underestimate the flow of fighters: Syria has many entry points, and Western security services recognize that they often do not know who has gone to fight. As the wars continue, the flow is likely to increase. The problem may prove a long-term one, as the networks and skills formed in Syria and Iraq today are used in the coming years to fight against the next grievance to emerge.

The foreign fighter threat—and the mitigating factors—can be pictured as a process from recruitment to fighting abroad to terrorism. But this process is not inexorable, and there are many possible exits and roadblocks on the route to terrorism. Indeed, the vast majority of individuals do not pass through the entire process. Most move off the road to terrorism, exiting at different stages in the process. Each conflict has its own dynamics that influence the likelihood that a given individual will travel all the way through the process to terrorism.

Using this framework, our policy recommendations focus on trying to identify opportunities to encourage potentially dangerous individuals to take more peaceful paths and to help determine which individuals deserve arrest, visa denial, preventive detention, or other forms of disruption. Steps include increasing community engagement efforts to dissuade potential fighters from going to Syria or Iraq; working more with Turkey to disrupt transit routes; improving de-radicalization programs to “turn” returning fighters into intelligence sources or make them less likely to engage in violence; and avoiding blanket prosecution efforts. Most important, security services must be properly resourced and organized to handle the potential danger. Taken together, these measures will reduce the likelihood that any one individual will either want to move or succeed in moving all the way down the path from concerned observer to foreign fighter to terrorist.

In sum, there is much that can be done to reduce the threat of foreign fighters committing terrorist attacks in the West. But almost inevitably, there will be some terrorist attacks in Europe or the United States carried out by returnees from Syria or Iraq. Terrorism, as the events in Paris so tragically remind us, has become a feature of modern life. It cannot be eradicated, only controlled. And the fallout of the civil wars in Syria and Iraq will certainly make that problem even more difficult.

Yet it is important not to panic and to recognize that both the United States and Europe have dealt with this problem before and already have very effective measures in place to greatly reduce the threat of terrorism from jihadist returnees and to limit the scale of any attacks that might occur. Those measures can and should be improved—and, more importantly, adequately resourced. But the standard of success cannot be perfection. If it is, we are doomed to failure and, worse, doomed to an overreaction which will waste resources and cause dangerous policy mistakes.

Download the complete paper, “Be Afraid. Be A Little Afraid: The Threat of Terrorism from Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” via this link.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Managing the Foreign Fighter Threat

January 14, 2015