Forget the Russians, the adult film stars, the Playboy bunnies, and the illegal payoffs covering up sexual misconduct. Forget the hotels full of foreigners enriching the president. And forget the convictions of his former campaign manager and his personal lawyer who may in the near future implicate the president himself in their wrongdoings.

The clearest potential violation of the law so far has been around a much less sexy issue—the issue that got President Richard Nixon in the end—obstruction of justice. In an exhaustively documented, 167-page 2nd edition of their report, “Presidential Obstruction of Justice: The Case of Donald J. Trump,” Barry H. Berke, Noah Bookbinder and Norman L. Eisen lay out the historical and legal bases for the concept and the charge. If, at some point in the future, some young lawyers on the House Judiciary Committee are instructed to draft articles of impeachment they will, no doubt, read this paper first and put its analysis to use.

For those who think obstruction of justice was something made up by the Democrats to get at President Trump, have a look at the Declaration of Independence. It begins with a long list of grievances against King George. Eighth in the list is the following: “He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.”

The first federal statute defining obstruction of justice was passed in 1831 and several have been added over the years to criminalize such conduct. Today, the authors argue, “President Trump faces the possibility of criminal liability for obstructing justice under three different theories.” The first is the obstruction of a proceeding such as congressional proceeding or a grand jury proceeding. The second is witness intimidation, and the third is conspiracy.

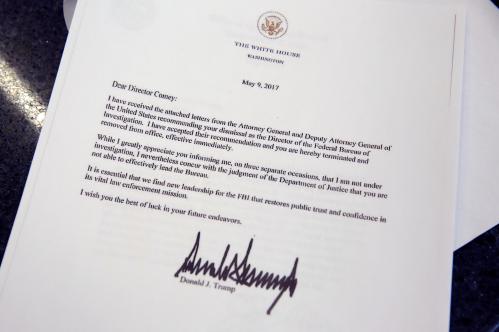

The clearest example of Trump possibly working to obstruct a proceeding is, obviously, his firing of FBI Director James Comey—an action Trump’s former strategist Steve Bannon called, “the biggest mistake maybe in modern political history.” Berke, Bookbinder and Eisen point out that while the president has the right to fire anyone who works for him, he cannot do so if it is “done for the corrupt purpose of obstructing an investigation.” The analogy they make is to the right of an employer to fire someone but not on the basis of their race, sex, or religion.

As for witness intimidation, the authors point to a long list of presidential tweets and statements ranging from his now familiar cry to end the “witch hunt,” to his attempts to discredit senior FBI officials, to his lawyer publicly speculating about pardons for his former colleagues, to revoking John Brennan’s security clearance because he led the “sham” Russian investigation. Witness tampering, according to the authors, “need not be explicit or overt. … Suggestive threatening, intimidating or persuasive statements are sufficient to support a case under Section 1512 (b).”

The third point the authors make has to do with corrupt intent—a phrase they admit is very vague. But here too, they cite a long list of Trump’s actions, including ordering Deputy Attorney General Rode Rosenstein to “…draft a memo on Comey’s conduct that the president would subsequently use as cover for Comey’s firing…” They go on to write that President Trump, “faces exposure under both the ‘offense clause’ and the ‘defraud clause’ of the conspiracy statute.”

Where all this goes, of course, is anyone’s guess until the full Mueller report is out (or at least submitted to Congress). According to the authors, the indictment of a sitting president “is not free from doubt.” Impeachment as a tool to discipline a president, however, is free from doubt; as is a sealed indictment which reserves prosecution for such time as the president returns to private life.

The first edition of this paper, published in October of 2017 was the first effort to lay out just how an obstruction of justice case might be made against President Trump. Now, ten months later, the second edition demonstrates that the president’s pattern of potentially obstructive conduct is even more extensive than previously realized. And there is likely more to come.

Commentary

Laying out the obstruction of justice case against President Trump

August 22, 2018