What has been called the “largest exercise in democracy”—eight weeks of voting in which over 800 million people participated—has concluded in India with a victory for the opposition, the Indian Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Narendra Modi. Although it earned slightly less than one-third of the vote nation-wide, the Indian single-party district system magnified the scope of the win. The BJP, along with its allied parties, has almost doubled the number of seats it holds in the Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament). Moreover, the BJP on its own now holds 282 out of 543 constituency seats, enough to allow it to form a government without any coalition partners. Meanwhile, the Congress Party suffered an historical defeat, now relegated to just 44 seats. Rahul Gandhi, the Congress Party’s prime ministerial candidate and scion of the Nehru-Gandhi family that has led the Congress Party since independence, barely won his own constituency in Amethi district, Uttar Pradesh.

This election has also changed the Indian electoral map. Four states—Modi’s own Gujarat, along with Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttarakhand—are now BJP-only states, with no other party representation in the Lok Sabha. Another six “union territories,” including Delhi and Goa, are also represented entirely by the BJP. Additionally, some 109 seats flipped from Congress to the BJP—most of them rural districts where the Congress Party has traditionally shown strength. One can drive from Mysore to Delhi while crossing only BJP constituencies.

The reasons for the BJP’s victory are multiple: an anti-incumbent mood among Indian voters given the state of the economy, the failure of the Congress Party to connect with younger voters, corruption scandals that saddled the current government, Modi’s 24-hour campaign which—much like Barack Obama in 2008—made innovative use of technology and social media, attracting millions of first-time voters.

While there are reasons to avoid the term “realignment,” this election may nonetheless mark a turning point in India’s political development more generally. Modi’s victory highlights four possible changes to the political system that, if they persist, could portend welcome shifts in the character of the democratic franchise as it is traditionally practiced in India.

India’s political system may become more issue-based and less identity-driven.

Historically, caste, religion, language, and ethnicity, have motivated significant blocs of voters. Although these factors—particularly the power of caste-based voting—are hardly irrelevant, in 2014 they took a back seat to punishing the party in power for presiding over falling growth rates, inflation, and a rupee that had lost up to 25 percent in value before recovering. Economic voting has occurred in India’s past; for example, in the 1991 elections, which took place amid a currency crisis. But in this election, the BJP and Congress adopted the rhetoric of conventional center-right and center-left parties, respectively. Modi, perhaps due to allegations of his own culpability in the 2002 communal violence in Gujarat, assiduously avoided religious politics and stuck to the pro-market, anti-red tape platform that earned his home state a reputation as a business-friendly place. Indian stock markets hit a record at the prospect of a Modi-led government. The rupee also strengthened to an 11-month high. Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi focused on rural poverty and unemployment, on the widening gap between rich and poor, and on basic needs such as food, education and health. That much of the political debate was focused on ideology rather than identity was a welcome development in the history of Indian politics.

Major Indian parties may rely increasingly on policies rather than handouts to gain support.

Nothing has been more certain in Indian politics than the expectation that the party in power will shower its supporters (and fence-sitters) with benefits in order to secure their vote. The Congress Party has expanded the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), a massive public works program that has provided jobs to close to 300 million households. Congress also enacted an ambitious right-to-education program, a national “rural livelihoods” program, as well as a food security bill that will ultimately deliver subsidized grains to two-thirds of the population. Supporters argue that these laws are critical to addressing India’s chronic poverty and inequality; critics deride them as old-fashioned budget-busting handouts. There is evidence that the NREGA, for example, helped the Congress-led coalition win in the 2009 general election. But the failure of the Congress’ welfare-based platform to cushion its collapse even in rural areas may signal the eclipse of welfare populism as a central electoral strategy. If true, this could prompt parties to modernize, to generate ideas, mobilize support, and govern on the basis of a consistent policy platform rather than entice backers through patron–client networks and seek power in order to gain control over state resources.

The election may signal a greater nationalization of politics.

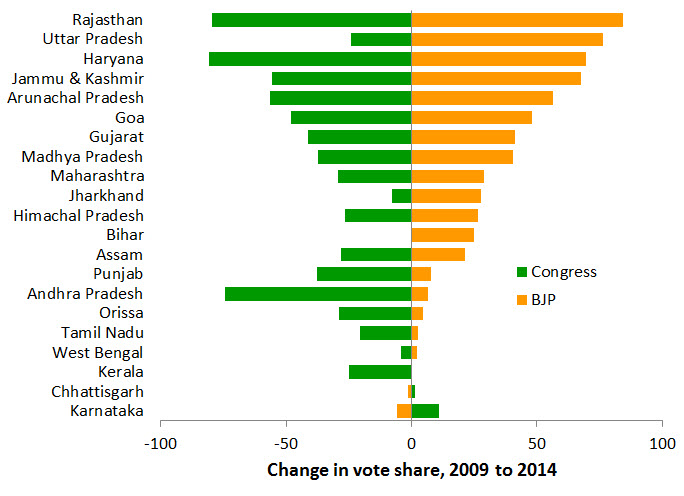

Much has been written about the rise of regional parties in India. Milan Vaishnav of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace notes that, rather than erode the stature of national parties, regional parties have more or less stabilized in terms of their relative power. The figure below compares the changes in vote shares for the BJP and Congress, by state, between the 2009 and 2014 elections. With the possible exceptions of Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh, most of the BJP’s victories came at the expense of the Congress Party. Unsurprisingly, Andhra Pradesh—which has been in the process of splitting into two states—is one of the few states where Congress’ losses were taken up by a regional party (Telugu Desam). Although the number of states where regional parties gained greater shares of votes than either of the two main national parties remained roughly the same, in some of the larger states—UP and Bihar—BJP popularity eroded the strength of regional parties.

Middle-class and urban citizens may continue to be mobilized.

One of the truisms of Indian democracy has long been the apathy of urban and middle-class voters. As mentioned above, Indian political parties make numerous direct appeals to poor and rural voters through a targeted transfers, but also through vote-buying schemes. Meanwhile, the middle classes have generally remained on the sidelines. It is not likely that these patterns have, all of a sudden, reversed themselves in this election. But we do know that urban areas experienced unprecedented voter turnout. There is also anecdotal evidence that the middle classes may have increased their turnout, prompted by pocketbook issues, anti-corruption sentiments, crumbling infrastructure, shoddy public service, and other concerns. If so, it would be the continuation of a trend in middle-class mobilization that has coincided with, among other things, a broad anti-corruption movement, street protests against a high-profile gang rape, the emergence of the Aam Aadmi (Common Man) party on an explicit “clean government” platform. All of these events were characterized by middle-class, primarily urban, support.

All of these developments are, in their own ways, precarious. Religion, for example, remains a strong factor in Indian political life. According to exit polls, only 9 percent of Muslims voted for the BJP which, although up from 4 percent in 2004, suggests that the largest minority religion remains excluded from the largest center-right party. The problems of vote buying are as rampant as ever, with party officials having been caught distributing cash, alcohol, and even drugs, in an effort to win votes. National parties have yet to make inroads in states such as Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, or Tamil Nadu, where regional parties remain dominant. And, the mobilization of middle-class or urban voters may prove temporary. But all of these changes, should they continue, would be unequivocally beneficial for the Indian political system, making it more institutionalized, stable, coherent, and transparent.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

India’s Political Development at the Crossroads

May 19, 2014