The United States is again at a crossroads of racial reckoning. The death of George Floyd and the 2020 summer of protests for racial justice added new urgency to ongoing discussions about the legacy of slavery and its contemporary implications for the lives of Black Americans. A key question at the root of this discussion is: how do we repair the harm – economic, physical, and psychological — caused to Black lives by slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, police brutality, and other manifestations of systemic racism?

The United States has used reparations—targeted initiatives intended to concretely repair a harm against a person or persons resulting from the collective action of others—as a means of acknowledging and atoning for its role in other atrocities, including the internment of Japanese Americans and the forced removal and destruction of six indigenous communities: the Ottawas of Michigan, the Chippewas of Wisconsin, the Seminoles of Florida, the Sioux of South Dakota, the Klamaths of Oregon, and the Alaska Natives. However, the descendants of Africans enslaved on U.S. soil have been notably absent from this history of reparative actions. While the task of reparations seems daunting to many Americans considering the scale of injustice presented by slavery and its aftermath, we believe this is a conversation the country needs to have.

“It’s because being American is more than a pride we inherit. It’s the past we step into and how we repair it.” – Amanda Gorman, The Hill We Climb

Recent polling data documents Americans’ general opposition to reparations in the form of financial payments to Black Americans as compensation for slavery. In 2014, 68% of those polled opposed such payments while only 15% supported them (17% were unsure). More recent polling in 2020 and 2021 suggests generally comparable results; in 2020, 63% of those polled were opposed to cash payments (31% supported; 6% had no opinion), while in 2021, 62% opposed (38% supported). There are also indications that this robust opposition remains despite a growing awareness of contemporary racial inequality – suggesting strongly that a racial awakening alone may not substantially alter policy views.

N = 1,012. Figure adapted from Reichelmann and Hunt (2021)

Support for reparations differs strongly across ethno-racial lines in the United States. In the 2014 poll, 79% of white Americans opposed cash payments as a form of reparations (6% supported; 15% were unsure). In contrast, only 19% of Black Americans were opposed (59% supported and 22% were unsure). In the 2021 poll, 72% of white Americans opposed this form of reparation (28% supported), while only 14% of Black Americans did (86% supported). Commonly-cited reasons for white Americans’ opposition to reparations include the difficulty of determining the monetary value of the impact of slavery alongside the fact that no one directly involved in the practice of slavery is still living. Other reasons center around the denial of any ongoing legacy of slavery and corresponding concerns about the undeserving nature of prospective recipients of reparations.

Given that white Americans gained the most from slavery and its compounded effects — a process referred to as unjust enrichment – is their widespread opposition to reparations rooted in maintaining this advantage? Research oriented toward better understanding the sources of white Americans’ opposition (and support) could go a long way toward helping us comprehend public opinion on reparations while shedding light on possible progressive paths forward. Our recent work contributes to that end by examining (1) how whites’ level of opposition varies across different types of reparations, and (2) how whites’ attitudes toward reparations are structured by sociodemographic and social psychological factors.

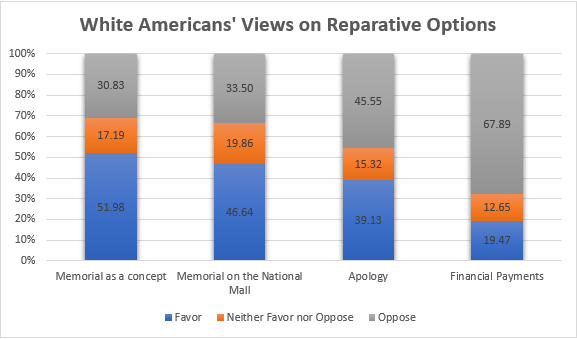

The types of reparations we examined range from purely symbolic (e.g., an apology; a memorial) to materially-based actions involving financial payments to Black Americans. Not surprisingly, white Americans are most supportive of symbolic actions and most opposed to cash payments. Regarding the factors structuring opposition, we found that white Americans who are older, more conservative, and who view race relations as unimportant, are most opposed to the range of reparative policies we examine. In addition, opposition to financial payments was also significantly shaped by gender, education, and social class identification; specifically, women, persons with lower levels of education, and self-identified middle class members were particularly opposed to this proposed remedy.

What are the practical implications of our research results for advancing discussions around reparations in the United States? The answer hinges, in part, on what we mean by reparations. Symbolic gestures from the Federal Government will encounter the least resistance from the white majority. Redistributing economic resources will encounter the most. Regarding the latter, our work suggests that opposition is most firmly rooted among persons whose social status may feel particularly precarious in an era of rising inequality. How then can we foster a sense of shared grievance around issues of racial injustice harming Black Americans?

Despite these obstacles, we believe that increasing public support for reparations (and closing the racial gap in opposition to such policies) likely hinges on appealing to Americans’ shared identities, empathy, and sense of democratic citizenship – i.e., fostering a sense that “we’re in this together.” That means finding ways to demonstrate to those most threatened by reparations how such steps can benefit the nation as a whole. Toward this end, academics and policymakers should frame discussions of reparations in line with broader projects of inequality-reduction and opportunity-enhancement. Our educational systems should strive to teach a complete and honest history of slavery and its legacy in ways that maximize receptivity among the widest possible audience. And, Congressional leaders should take the next step in advancing the reparations discussion via a commission to study and develop reparative proposals for African Americans, as proposed by HR 40 — a bill that has been brought before the House of Representatives in every session since 1989, but has never gained significant traction in Congress. Taking such steps would facilitate a long-overdue conversation between citizens and the government that oversaw slavery and its lasting legacy.

Ashley V. Reichelmann is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Virginia Tech and the Associate Director of the Center for Peace Studies and Violence Prevention. Her work broadly focuses on how past violence impacts modern racial identity and intergroup relations.

Matthew O. Hunt is Professor of Sociology at Northeastern University. His primary research interests involve intersections of race/ethnicity, social psychology, and inequality in the United States.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How we repair it: White Americans’ attitudes toward reparations

December 8, 2021