This op-ed was originally published in The Hill on October 17, 2019.

Social Security is entering a new era. Starting next year, benefits will be sustained not only by current payroll taxes but also by withdrawals from reserves accumulated over the last three decades. In about 15 years, however, the Social Security trust funds will be depleted. At that point, the earmarked revenues will cover only about 80 percent of the benefits of the program promised to Americans under current federal law.

Reforming Social Security to make it financially sustainable for the long run and modernizing benefits to better meet the needs of 21st century retirees and the disabled will require higher payroll taxes. Aversion to tax increases causes skittish lawmakers to delay addressing the unavoidable challenges of Social Security, even though the required adjustments grow more wrenching every year that a feasible solution is delayed.

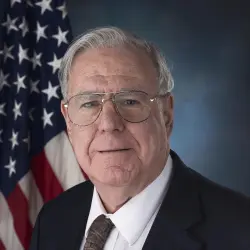

Breaking with this pattern, Chairman John Larson of the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security has stepped up to the challenge. Joined by more than 200 cosponsors, he has introduced the Social Security 2100 Act to address the financing problem and to raise benefits. The bill proposes to raise benefits across the board with the percentage increase being largest for those with the lowest lifetime incomes. It will index benefits with an inflation measure reflective of the consumption patterns of the elderly rather than one based on consumption of workers and establish a minimum benefit equal to 125 percent of the poverty level for those who have worked for pay for 30 years or more, with less for workers with fewer years of earnings. It will also reduce the amount of Social Security benefits subject to the individual income tax.

To strengthen the future financial viability of the program and pay for these benefit enhancements, the bill would increase the payroll tax rate by 2.4 percent over 24 years through annual 0.1 percent increases, half paid by workers and half paid by employers, beginning in 2020. The current 12.4 percent rate would reach 14.8 percent in 2043. The current payroll tax for Social Security applies only to earnings below an indexed threshold of $132,900. The bill would eventually apply this tax to all earnings. The payroll tax would be applied immediately to earnings over $400,000. When the lower threshold, which would continue to rise as average wages grow, reaches $400,000, all earnings are taxed.

Larson and his cosponsors deserve praise for developing a plan that Social Security actuaries estimate would put the program on sound financial footing for the indefinite future without slashing benefits. Still, we think they should pause to consider several tough questions.

First, are the Social Security benefit increases proposed in the bill well designed to meet the needs of the elderly and disabled who are economically hardpressed? The benefit increases that the bill calls for will put additional dollars in the pockets of those whose retirement incomes are already adequate as well as those of people who clearly need help. Similarly, reducing benefits subject to the individual income tax would boost the after tax retirement income of the 55 percent of beneficiaries with the highest incomes whose benefits are partially taxed.

Among this group, the richest individuals would benefit the most. We think that doing something to help the oldest retirees, whose assets and private pensions may have been depleted, and widows and widowers, who must adjust to living in a household with one benefit rather than two benefits, should also come before increases across the board, as should the provision of credits toward future Social Security benefits for parents who curtail work for pay so that they can care for small children.

Second, given current budget deficits and competing domestic priorities, does it make sense to devote more than three quarters of $1 trillion over the next decade to higher benefits for the elderly and disabled at all income levels? Would this commitment crowd out needed spending on such other benefits for the elderly and disabled as prescription drug reform and improved long term care, as well as for broader national priorities like education, infrastructure, health care, and child care?

Third, while the bill should be commended for its fiscal responsibility, as it would increase payroll tax revenues by $1.3 trillion and benefit payments by $817 billion over a decade, the large payroll tax increase for Social Security may hamper efforts to maintain Medicare hospital insurance, which also depends on the payroll tax and is projected to be unable to fully pay providers after 2026. It could also sap the willingness of Americans to consider tax hikes needed to pay for other urgent public needs. We think everyone, but Democrats especially, should worry about the emergence of a revenue system that taxes earnings disproportionately heavily and capital very lightly. This danger is especially acute after the 2017 tax legislation, which slashed taxes on capital income.

We applaud efforts to secure Social Security for future generations. We believe, however, that Social Security reform legislation should target benefit increases on those with demonstrable need so that tax revenues can be preserved to meet other service needs of the elderly and disabled and to finance spending on other urgent domestic priorities.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. The authors serve together on the board of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which takes positions on issues discussed in this article, but the authors are solely responsible for the content of this article. No outside (non-Brookings) party had the right to review this work prior to its circulation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edHow to reform Social Security for future generations of Americans

October 31, 2019