Editor’s Note: This text is based on the author’s World Bank working paper on

“

Poland’s New Golden Age: Shifting from Europe’s Periphery to Its Center

.

”

Poland entered 2015 in high spirits. Its GDP per capita based on purchasing power exceeded $24,000 and reached 65 percent of the Western European (eurozone) level of income, the highest absolute and relative level since 1500-1600 A.D.—the “golden age” when the country stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea.

Actual individual consumption, which includes the use of public services financed by the government, rose even higher and exceeded 70 percent of that of the West. The quality of life seems to have increased in tandem, as reflected in international well-being ratings such as the OECD Better Life index, where Poland does better than what the income level alone would suggest. The country’s sports results have also turned around: within the last six months alone, Poland’s national team became a world champion in volleyball, won a bronze medal in handball, and beat the current world champions in soccer—Germany—for the first time ever. No wonder than that more than 80 percent of Poles are satisfied with their lives, up from only half at the beginning of transition.

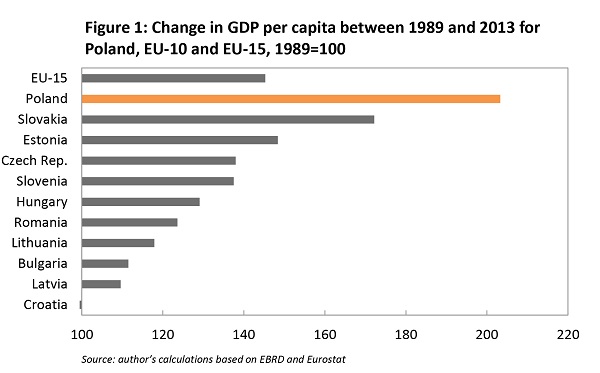

These successes follow more than 20 years that were likely the best in Poland’s history. Since 1989, the country’s GDP per capita more than doubled, coming ahead of all European peers (Figure 1). Exports increased more than 25 times and came close to $250 billion in 2013. Since 1995, Poland has also grown faster than all large economies at a similar level of development, as reflected in average GDP per capita growth. After 23 years of uninterrupted growth—including during the 2008-09 global financial crisis, when Poland was the only EU economy not to sink into a recession—it is close to beating the world’s historic growth records.

Quite remarkably, Poland’s growth has been based on brain power, entrepreneurship, and hard work, not on natural resources or financial steroids. Poland is a net energy importer and its public and private debt levels are well below the European average. Finally, the remarkable growth in the last 20 years has not come at the expense of the poor: inequality increased following the transition, but then it came down and now hovers around the EU average.

What Were the Sources of Poland’s Economic Miracle?

First, from the very beginning Poles seemed to know where they were going: towards European integration. In the process, they adopted Western institutions, rules, and social norms that are at the very foundation of economic development: the rule of law, independent monetary policy, robust competition, free press, and democracy.

Second, Poland expanded the quantity and quality of education. Today every second young person studies at the university level, above the EU average, up from only one out of ten in 1989. Despite relatively low spending on education, young Poles are also well educated: according to the OECD PISA 2012 study, Polish 15-year-olds are more functionally literate than most Western European and North American peers.

Finally, Poland also benefited from large inflows of EU funds that helped connect Poland with Western Europe by highways for the first time ever. An improved business climate also helped, with Poland leading the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking among the EU and OECD countries in the pace of reforms. Lastly, the country’s strong supervision and conservative risk profile has helped maintain a healthy utility-like banking sector.

What Gave Poland an Edge Relative to its Regional Peers?

There were a number of likely factors. First of all, Poland seems to have been more thorough in introducing market oriented-reforms at the beginning of transition (as well as during the dying days of socialism). This helped spawn a private sector boom and move the country out of the post-transition recession already in 1992, before others. Poland was also quick to follow the early market reforms with robust institutional building, and was rewarded with an accession to the OECD in 1997. Quite importantly, it managed the privatization process in a broadly efficient and transparent way. There are no Polish oligarchs today. Lastly, Poland benefited from a large and rapidly growing domestic market, which helped to insulate it from external shocks, such as those in 2008-09.

Poland’s performance in the last quarter of a century has been not much short of a miracle. As a result, Poles never had it so good before in terms of the level of income and quality of life. But the race to catch up with the West and permanently escape the European periphery is not over: further reforms are needed, especially as regards innovation, tertiary education, and population ageing. Let Poland’s new golden age begin.

Commentary

How Poland Became Europe’s Growth Champion: Insights from the Successful Post-Socialist Transition

February 11, 2015