The global technology industry is hedging its bets. As the United States and China compete for technological supremacy in advanced semiconductor design and manufacturing, software, and other core technologies, global high-tech companies do not plan to pick sides. Rather, they pragmatically aim to compete in both Chinese and U.S. ecosystems regardless of the extra cost and complexity involved. This is the message from 158 senior business executives working for American, Chinese, European, Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean global high-tech firms whom we polled about the impact of U.S-China tensions on their industry. While these executives regard as inevitable that American and Chinese technological spheres of influence will to some extent separate, they also expect Chinese systems and solutions suppliers to continue to rely on globally sourced (rather than Chinese-developed) technologies. In addition, these executives expect multinational companies of all stripes to double down on their efforts to keep competing in the Chinese market.

With core technologies a central issue in U.S.-China relations, the Commerce Department and other agencies have recently placed greater restrictions on the technologies that can be exported to China, as well as added major Chinese tech companies to the blacklist of firms that can purchase American technology or receive U.S. investment. At the same time, the Chinese government has said it seeks “technology independence”—the vague goal articulated in the most recent five-year plan to reduce the reliance of Chinese high-tech firms on non-Chinese suppliers.

The Biden administration now faces hard choices about whether to continue, accelerate, or alter the policies it inherited from the Trump administration seeking to constrain Chinese access to cutting-edge technology. Indeed, the Biden team is currently carrying out a broad review of U.S. policies toward China that is considering how to best approach Beijing on a range of issues that span military, trade, and technology relations.

Yet for all the geopolitical tension between the United States and China, the outcome will not be driven solely by the White House and Zhongnanhai. How the private sector perceives and responds to those tensions matters a great deal too. Many of the high-tech goods at the center of U.S.-China tensions are manufactured by global companies that compete in both U.S. and Chinese markets or rely on technologies developed or manufactured in the United States and China. Whether these companies commit more heavily to the Chinese or American ecosystems, exit one or the other, or instead play both sides off each other, will have significant implications for the policy options available to officials in Washington and Beijing.

Most respondents in our poll expect both the U.S. and Chinese governments to push policies that encourage greater decoupling, causing the global technology industry to increasingly bifurcate into two spheres. They predict China will continue its traditional industrial policy model of subsidizing national champions in the technology industry and tilting procurement rules to the advantage of local companies. The results of such efforts: Chinese companies will take the lead in some emerging high-tech systems and solutions markets, and while China will continue to close the gap in overall technology capability, the United States will maintain its overall lead in core technology capabilities, such as semiconductors and operating systems. As the U.S. government ramps up competition with China, these executives do not recommend that Washington emulate Beijing through the use of subsidies and politically driven procurement. Rather, they argue for both greater U.S. openness toward foreign capital and tech and a more activist approach to limiting the transfer of key technologies abroad.

A dispatch from industry

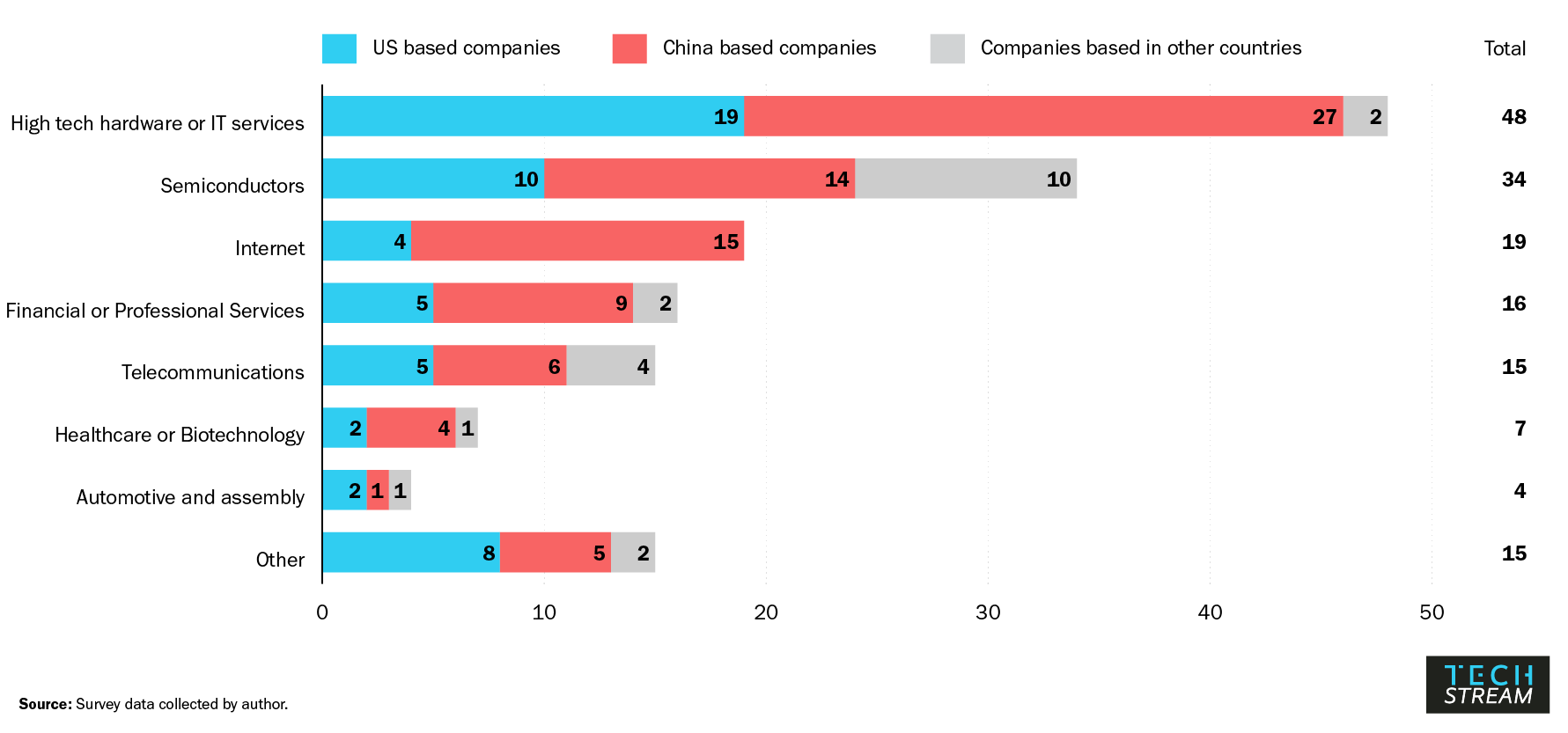

Figure 1: Breakdown of respondents by industry and the location of their headquarters

As Figure 1 illustrates, respondents are drawn from companies at the fault-line of cross-border trade, investment, and product development in the United States, China, and other countries with advanced manufacturing capabilities. Approximately half of the respondents work for companies headquartered within China, and the remainder for U.S., Japanese, Taiwanese, Korean, UK, or German firms. Roughly half work in the hardware industry, including IT and semiconductors. Another 20% work in internet or telecommunications companies. The respondents represent a senior group of executives, including board members, chairpersons, CEOs, CxOs, vice presidents, and general managers. While the group does not represent a random representative sample, it offers a snapshot of how business leaders perceive and will react to the competition between the United States and China for technological supremacy.

An expectation that government policies will continue to drive decoupling

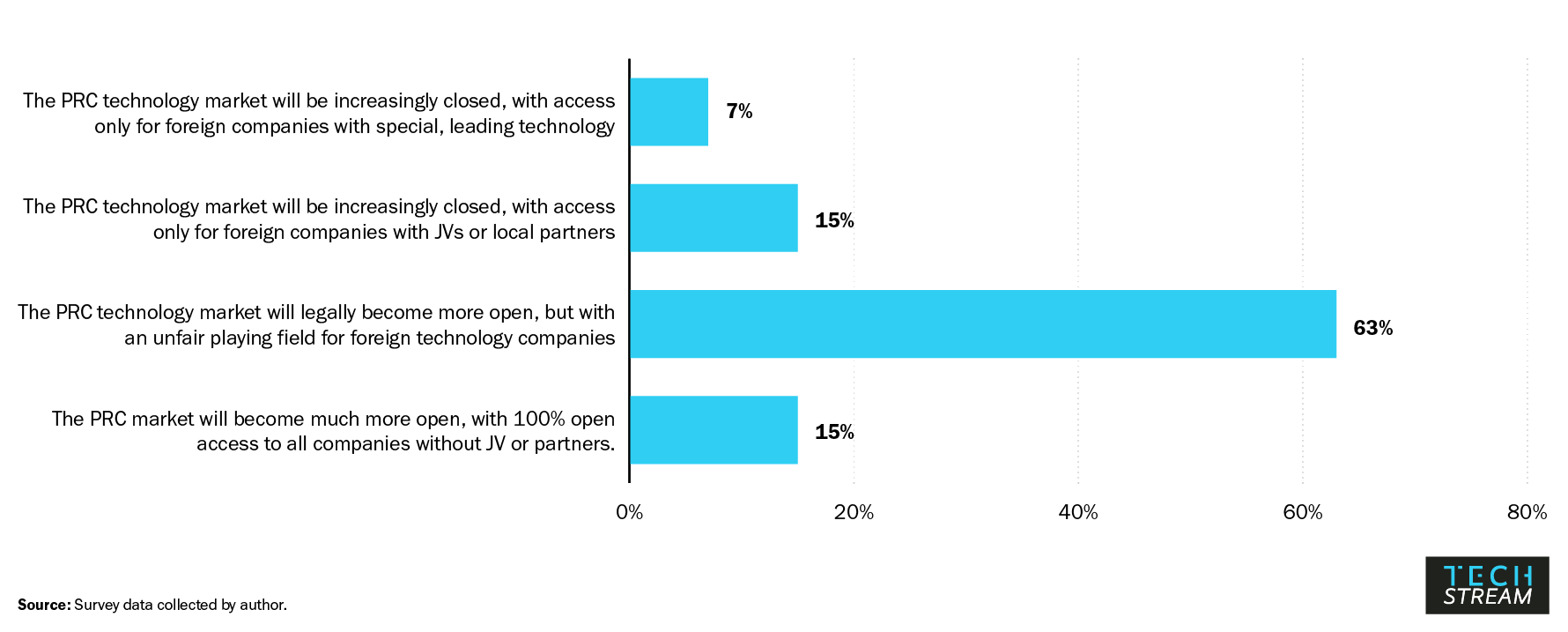

Survey respondents share a clear perspective on decoupling. While there are expectations that President Joe Biden will modify Washington’s approach toward Beijing, respondents expect that both the United States and China will double down on the actions that, to date, have encouraged a decoupling of the two countries’ economies. Despite calls for fair access for American firms to the Chinese market, 85% of respondents believe that the Chinese government will either increasingly close its tech markets to foreign firms or allow fewer legal restrictions on their operation while providing less fair operating conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: What will be the future policy of the PRC government regarding access to its technology markets?

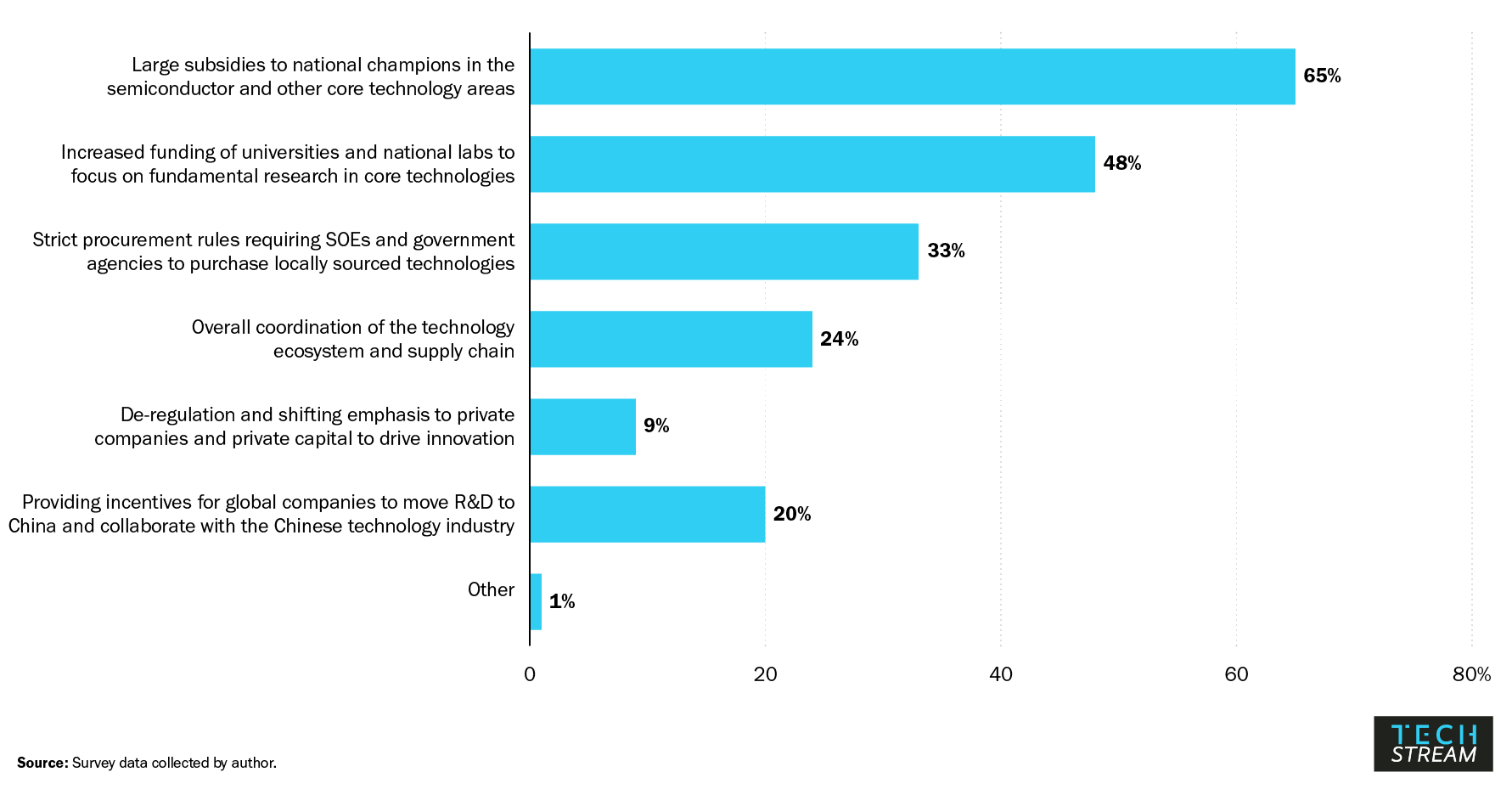

Two thirds of respondents indicate that they expect Beijing to use heavy subsidies to support national champions and achieve self-reliance. One in three respondents indicate that they expect strict procurement rules will be used to require government-affiliated firms to buy local. Half of respondents expect increased funding to Chinese universities and labs to spur basic research. Only one in ten respondents expect the Chinese government to pursue deregulation initiatives and let the private sector take the lead (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The 14th Five Year Plan as outlined includes a push for self-reliance in technology. What do you think will be the top 2 policy tools the PRC government will use to achieve self-reliance in technology?

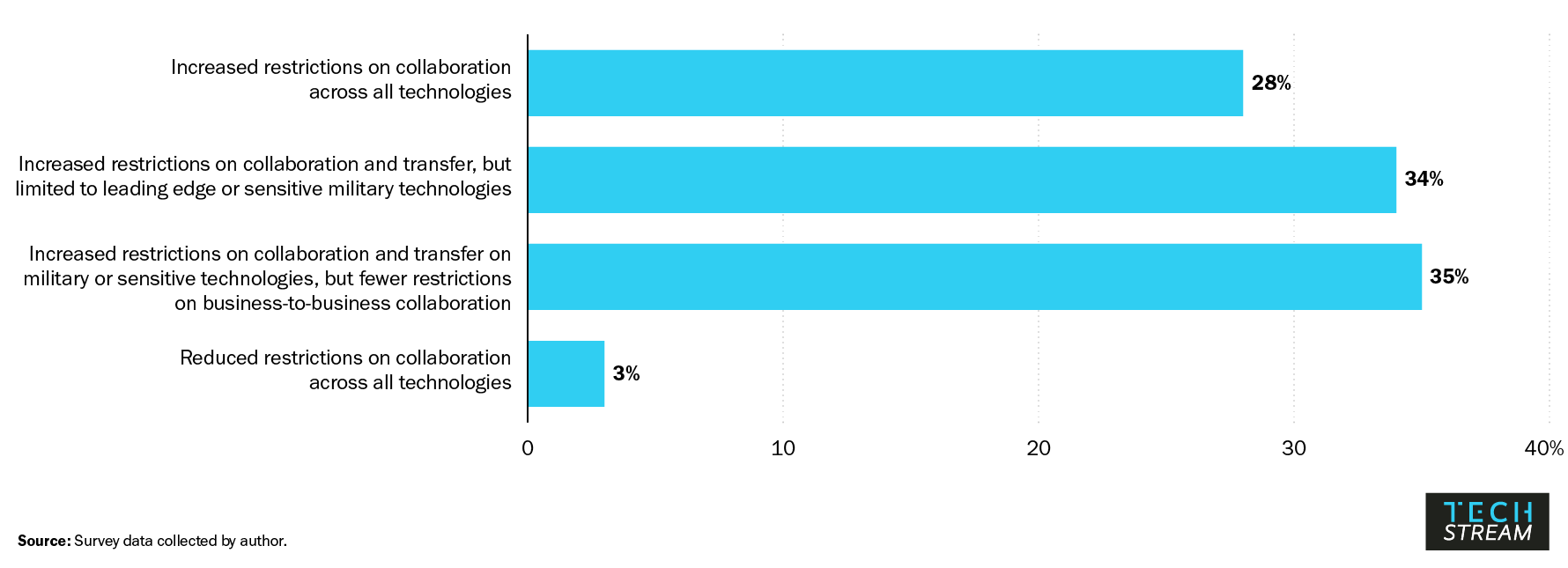

The Chinese government aims to protect its world-class smartphone, PC, smart device, and telecommunications equipment industries and ensure continuity of supply by reducing these industries’ dependence on high levels of imported technologies, including from the United States. Ensuring such continuity will be challenging if U.S. restrictions continue to expand as survey respondents believe. Some 62% believe that the U.S. government will increase restrictions on high-tech exports, and less than 5% expect a broad loosening of restrictions. In short, respondents expect the Biden administration to maintain the basic trajectory of the Trump administration’s export control policy toward Beijing (Figure 4).

Figure 4: What do you expect to be the future policy of the US government towards the Chinese technology industry?

Mutual dependence continues

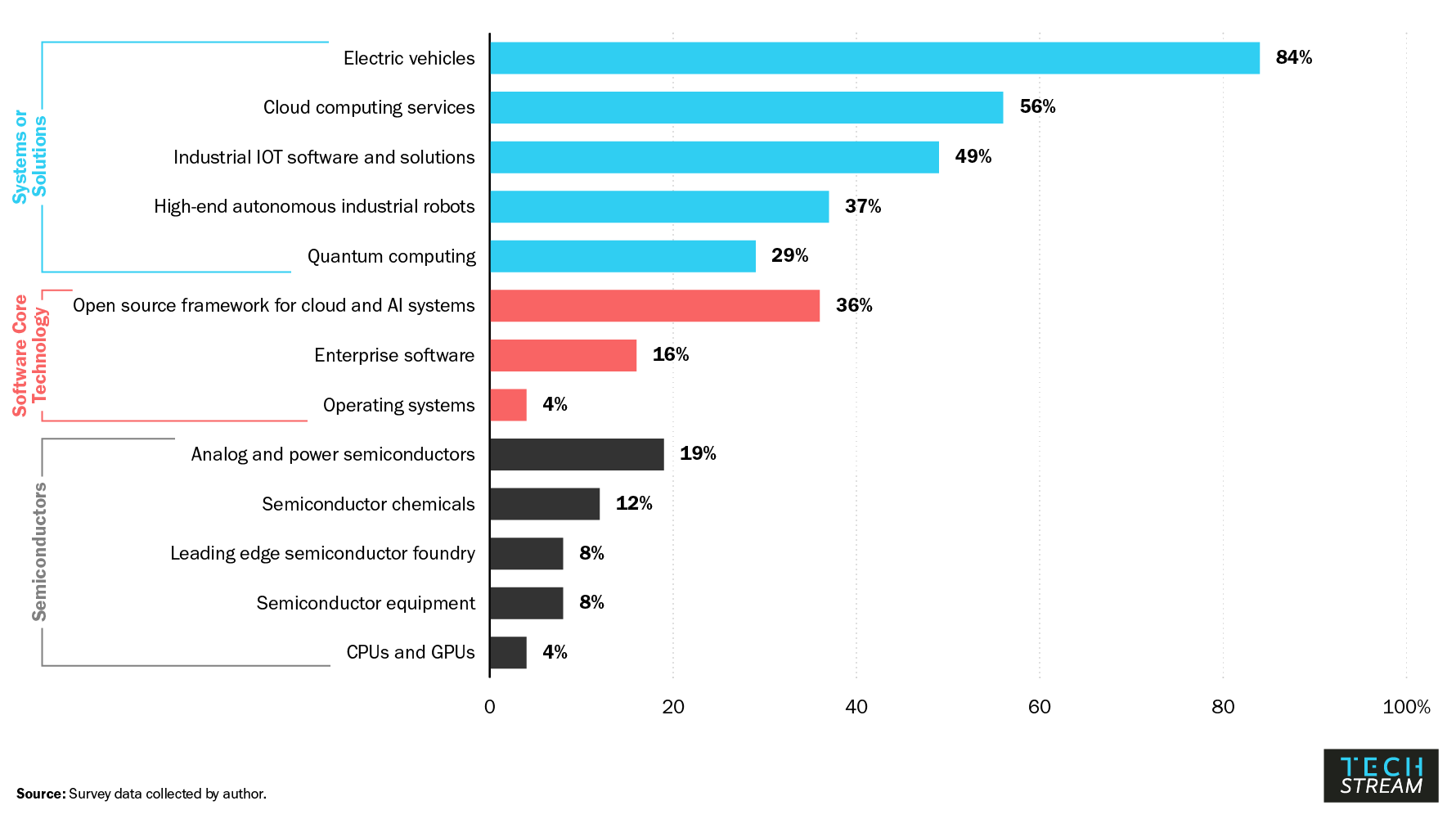

Despite continued U.S.-China tensions, respondents do not expect the global distribution in technology industry market share to shift. Therefore, the mutual dependence of U.S. and Chinese technology industries will continue. As Figure 5 illustrates, respondents expect Chinese companies to continue to be more successful developing system or solution-level applications of technologies, rather than core technologies. When asked about the prospects of Chinese companies to be successful in a series of technology areas, respondents were more optimistic about Chinese company efforts in solutions, systems, and services (such as electric vehicles, cloud providers, and industrial robots) than in core components (such as semiconductors and core software) or the upstream advanced manufacturing and design industries (such as leading edge foundry and semiconductor equipment or materials).

For instance, 84% of respondents indicated that within five years China will headquarter a top-three global electric vehicle company, and more than half believe that China will headquarter a top-three global cloud services provider (indicating they believe a Chinese vendor will surpass one of Amazon, Microsoft or Google). However, less than 5% believe that China will headquarter a global top-three GPU, CPU, or operating systems provider. Less than 10% indicate that China will successfully build a global top-three player in leading edge semiconductor foundry or semiconductor tools.

Figure 5: In which segments will a Chinese company have top 3 global market share by 2025? (Choose all that apply)

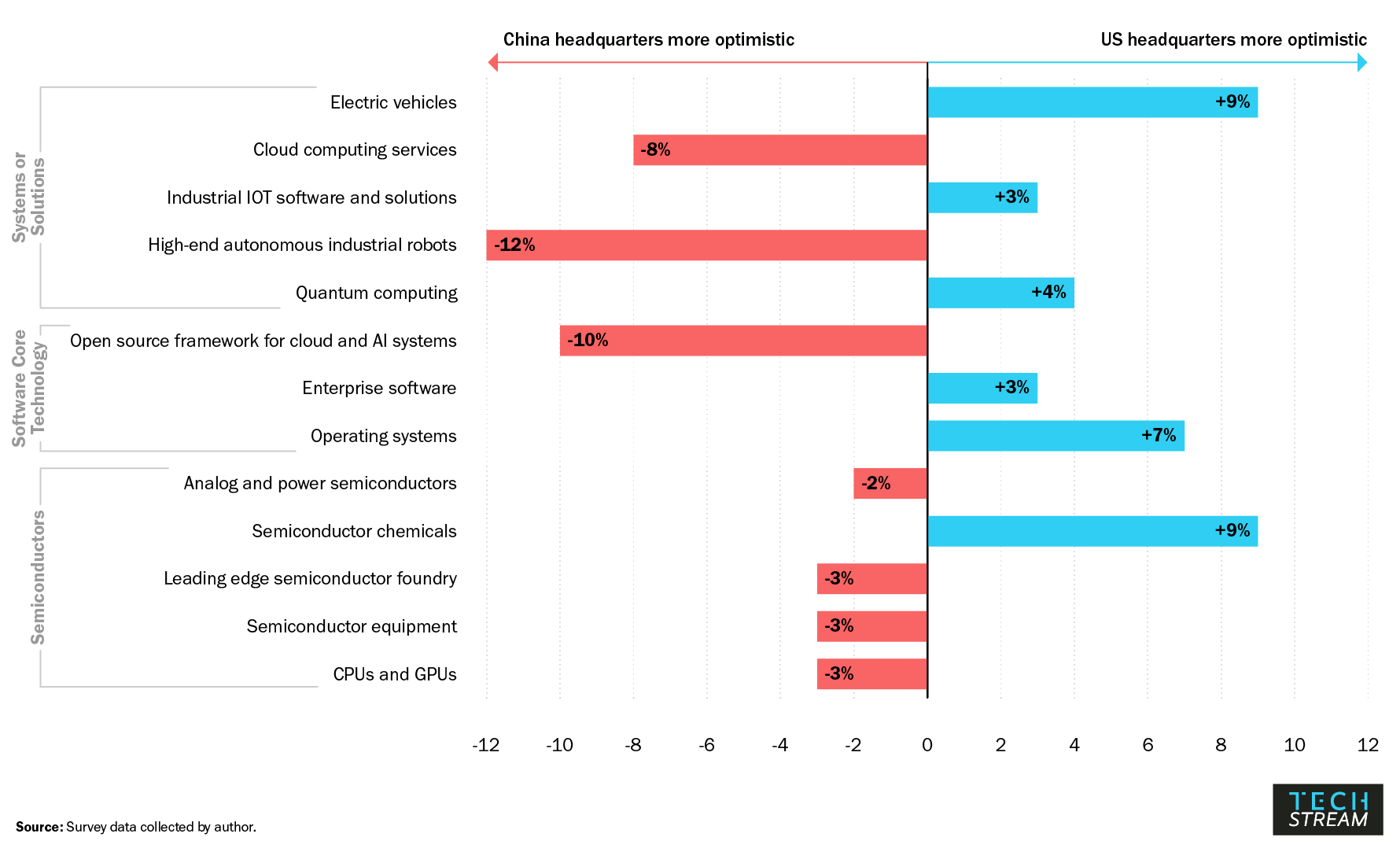

Across respondents from companies based in China, America, and in other Asian and European countries, there was little difference of opinion regarding the potential success of Chinese companies in these emerging industries. Respondents from Chinese-headquartered companies were more optimistic on average in six technology categories, but they were less optimistic in the remaining seven. And in only one category was the gap between Chinese and American respondents was greater than 10 points.

Figure 6: In which segments will a Chinese company have top 3 global market share by 2025? (Choose all that apply)

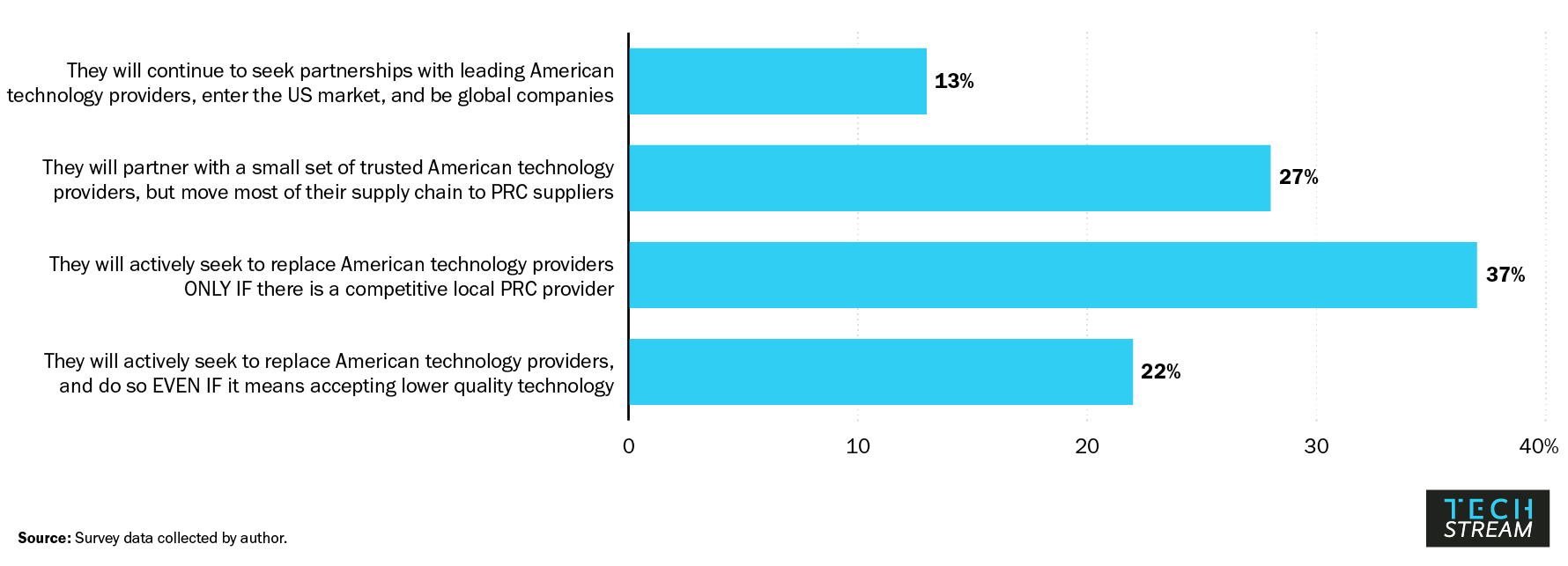

As Chinese firms establish leading positions in emerging technology sectors, respondents expect that Chinese companies will pragmatically continue to work with American suppliers. This mirrors the basic math that drives the structure of the global technology industry today: With Chinese system (phones, PCs, servers, surveillance cameras, telecommunication equipment) companies holding far higher global market share than the country’s semiconductor companies, reliance on global, non-Chinese sources of technology is inevitable. Executives at Chinese companies understand this reliance creates a business risk, so it is no surprise that nearly 90% of respondents indicate that Chinese companies are searching for alternatives to imported technologies (Figure 7).

Figure 7: What will be the technology sourcing strategy of Chinese technology corporations that depend on imported technology?

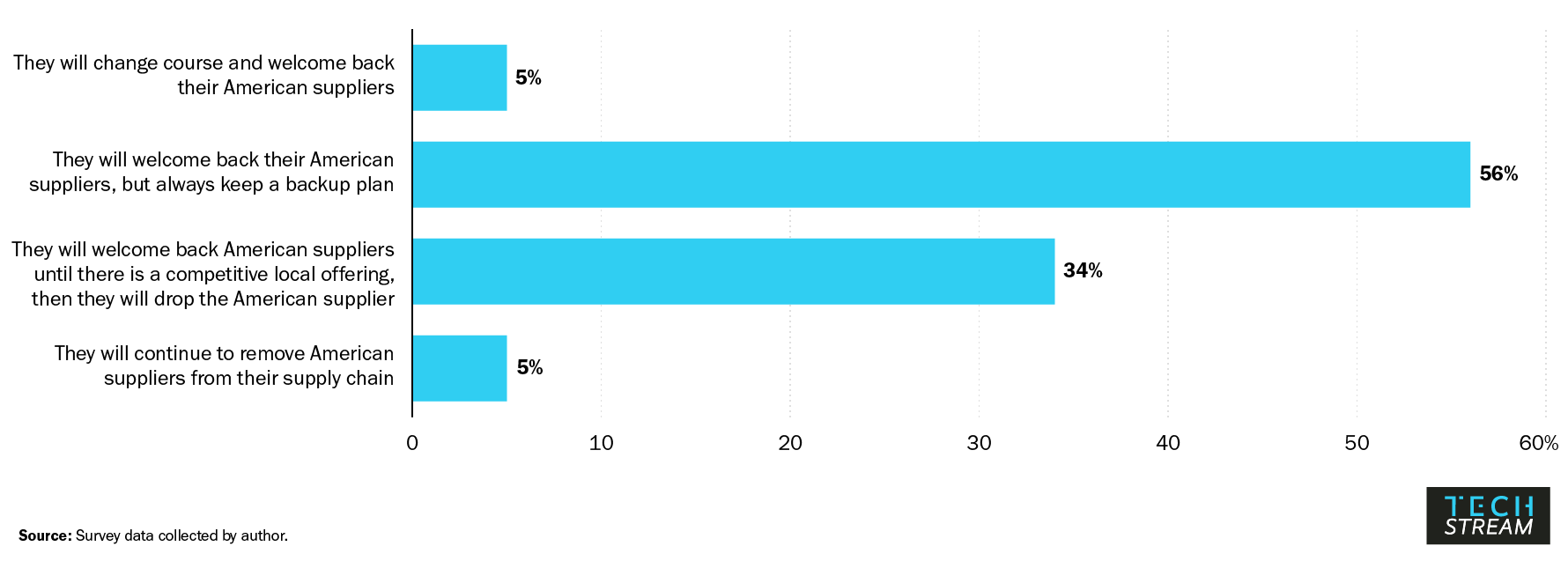

Future changes in U.S. policy will impact the path that Chinese companies take but potentially only in the short-term. Only 5% of respondents see Chinese companies replacing American suppliers no matter U.S.-government policy. The remaining respondents expect Chinese companies to welcome back American suppliers to which they are currently denied access—but expect these Chinese companies will have a back-up plan or replace the American suppliers if and when there is a comparable Chinese-sourced product or technology. The success of American suppliers with Chinese customers depends on how long they can stay ahead of Chinese alternative suppliers, both in technology and in the total supplier value proposition (including price, quality, time to market, etc.) In other words, market and technology factors will determine success, not policy.

Figure 8: How will Chinese companies change their technology sourcing if the US reverses the technology policies (e.g., entity listing, export controls, etc.) of the last few years?

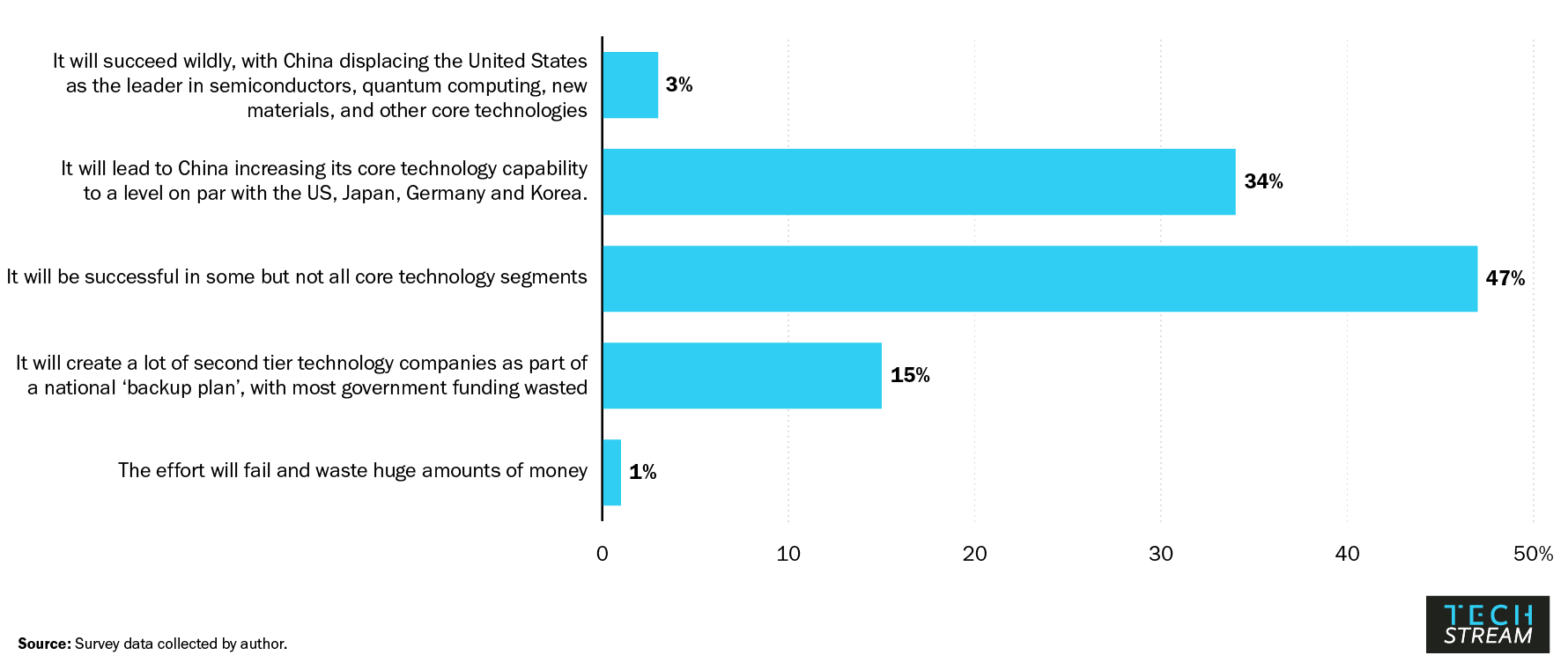

This expectation that Chinese firms will continue to rely on American technologies to maintain competitiveness is consistent with their view of the evolution of the tech industry. One in four respondents believe American companies will dominate global technology markets in ten years. Only one in three respondents believe China will fully catch up across all sectors within 10 years, with a greater number believing that “self-reliance” success will be uneven across specific sectors of technology. And 16% believe the Chinese government efforts will be a waste of money (Figure 9).

Figure 9: In 10 years, what is the most likely outcome of China’s push for self-reliance in technology?

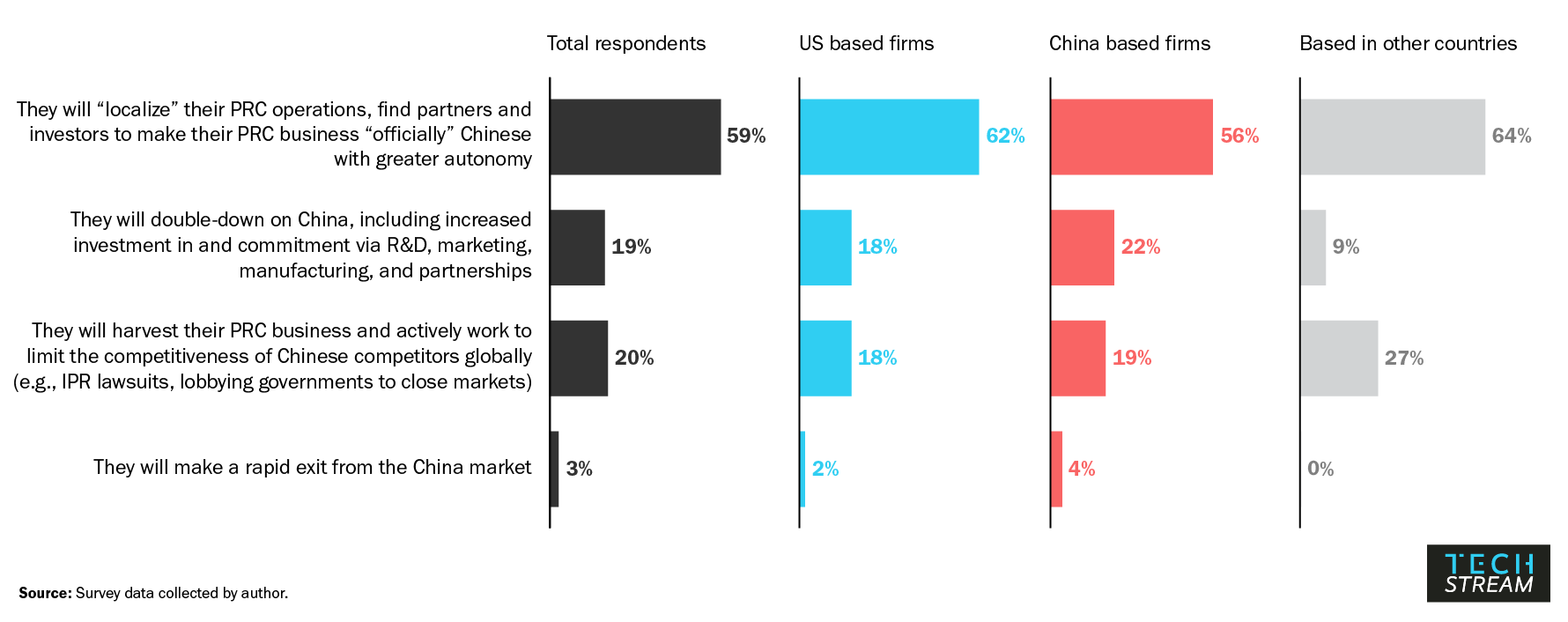

Of course, dependence cuts both ways. Chinese systems and solutions companies’ reliance on American-sourced technology indicates that American technology companies in the semiconductor and other core technology industries will continue to rely on the Chinese market for customers and revenues. This is likely why, as Figure 10 shows, respondents from American companies expressed a desire to maintain their presence in China (while complying with U.S. laws and export controls). Four out of five respondents will continue to compete with vigor in China, with more than half of those focusing on localizing their operations to meet the unique and challenging competitive environment in China. There is a substantial minority of multinational firms, comprising 1 in 5 respondents, that will turn away from the Chinese market and aim to blunt the rise of Chinese competitors in global markets. It should be noted that as most respondents from multinational firms have a role in or lead their company’s China operations, they have an interest in those operations being successful.

Figure 10: What over-riding strategy will non-local (US and other non-PRC countries) technology corporations most likely use for competing in China?

Carving up the world—with allies in the neutral zone?

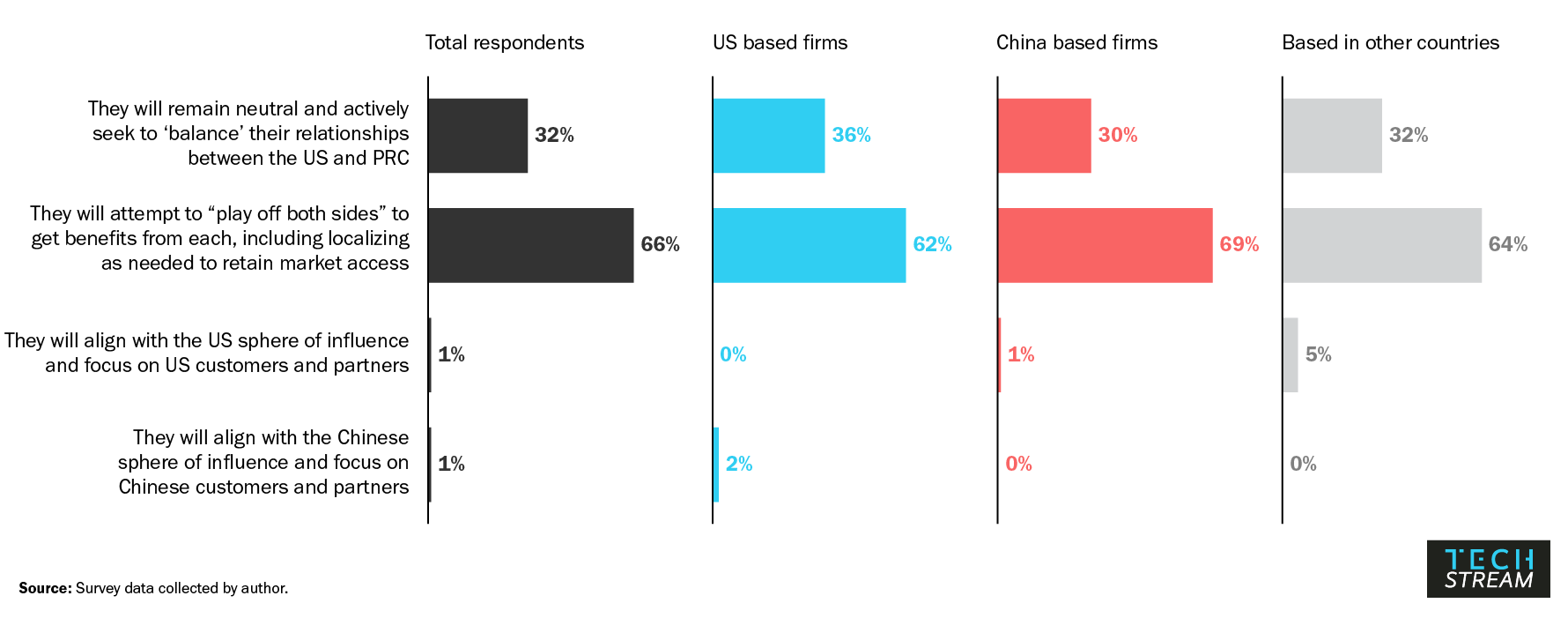

Tensions between the United States and China pose difficult questions for tech companies headquartered outside the two countries. But based on our survey results, these firms do not plan on choosing sides. As Figure 11 illustrates, an overwhelming 98% of respondents indicate that these companies from third-party countries will align with neither China nor the United States. Two out of three respondents expect companies based outside the United States and China to play the two countries off one another to get benefits from each. As Figure 10 above shows, two out of three also said they would further invest in China or localize operations there, despite more than 95% believing multinational companies in China will face an uneven playing field there.

Figure 11: What will be the most common strategic approach of non-US and non-PRC companies in response to potential ‘decoupling’?

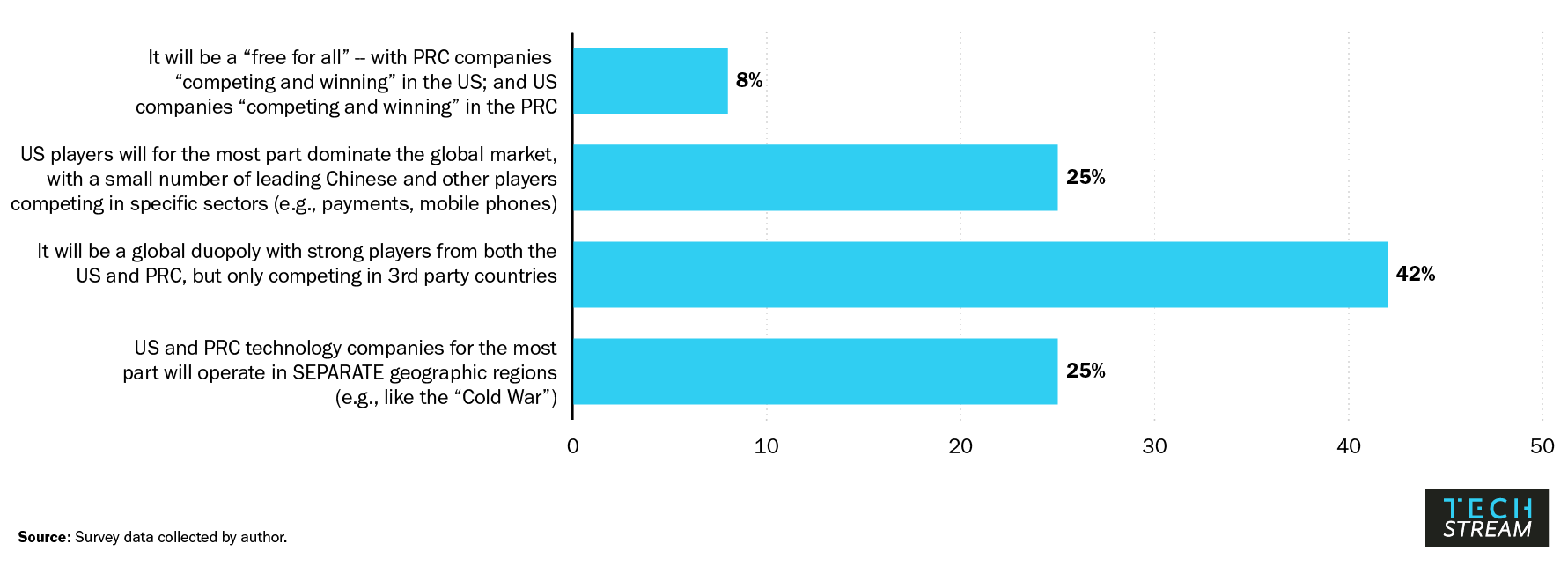

Respondents will need to develop this strategic approach, as they believe the global technology market will bifurcate in the next decade. Two in three respondents believe that Chinese and U.S. companies will primarily compete in third-party countries (i.e., not in each other’s home markets). One fourth of respondents indicate that countries will fall into one of two blocs served either by Chinese or American firms. Less than a tenth of respondents believe that in 10 years the technology industry will be global and open (Figure 12).

Figure 12: What will be the competitive dynamics of the global technology industry in 10 years?

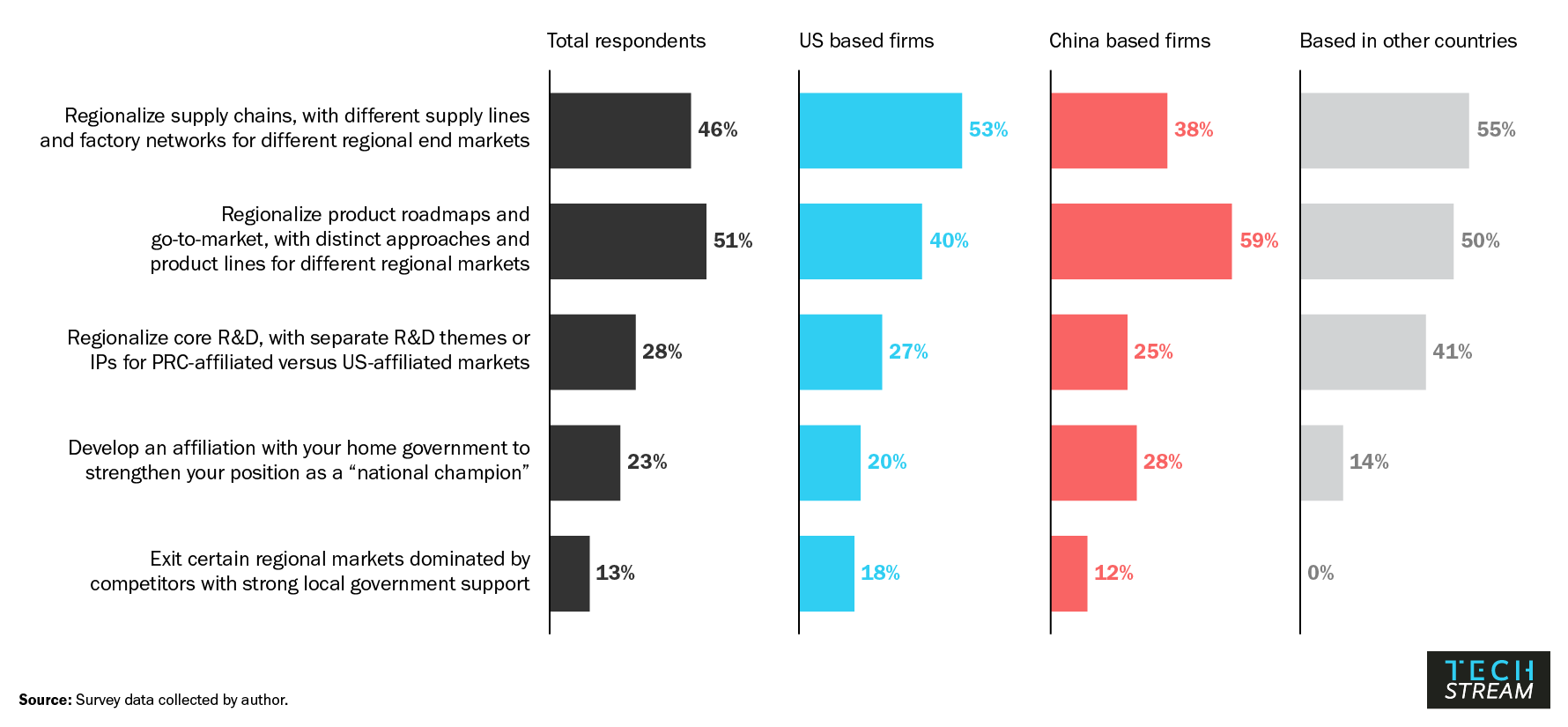

The implications of these findings are that multinational companies will no longer be truly global. They will not operate in the same way in Chinese and U.S. spheres of influence or ecosystems. Multinational companies will compete globally while customizing their offerings for Chinese and U.S. spheres. Each company will take steps unique to their market, competitive positions, and source of differentiation. As Figure 13 shows, more respondents expect companies to take on the most complicated internal split of operations—separating basic R&D and core intellectual property into different themes for different markets—than plan to exit either market. Companies will bear this cost and complexity—because both spheres are important, and both are huge markets.

Figure 13: Over a 5-year or longer-term time frame, what moves will companies in your industry take to deal with political tensions? (Select up to 2)

Views on the path forward for U.S. policy

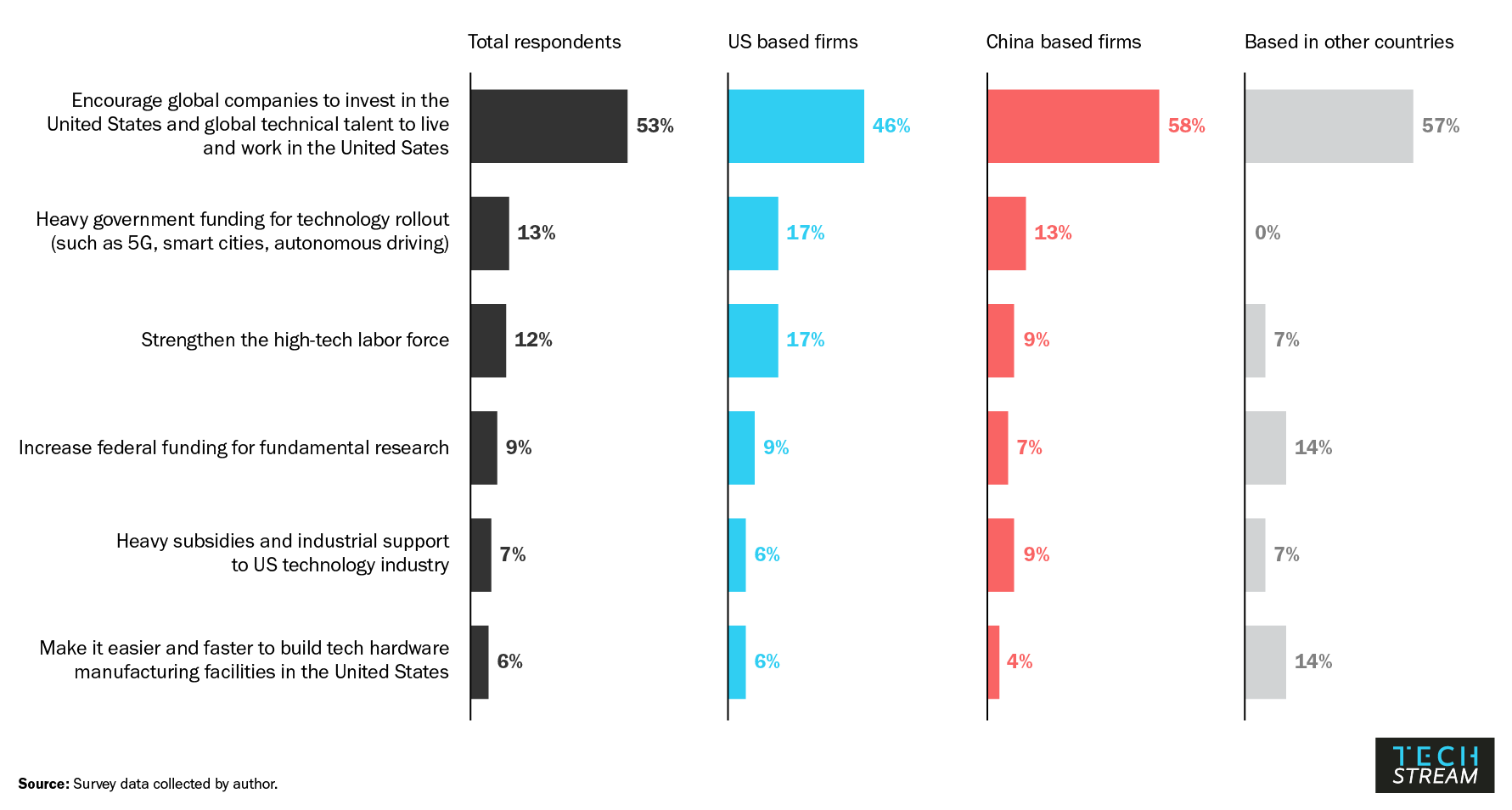

The survey also asked executives what advice they would give to American policymakers seeking to support the U.S. high-tech industry. Leaders at both Chinese and U.S. companies chose doubling down on globalization as their primary recommendation, with a majority (53%) suggesting the United States adopt policies that “encourage global companies to invest in the United States and encourage global technical talent to live and work in the United States.” There was little appetite (in a group of admittedly globally oriented executives) for the United States to adopt the core components of the PRC industrial support model, such as major subsidies or turning the government into a major customer for technology deployment (Figure 14).

Figure 14: What should the United States do to increase its competitiveness in technology?

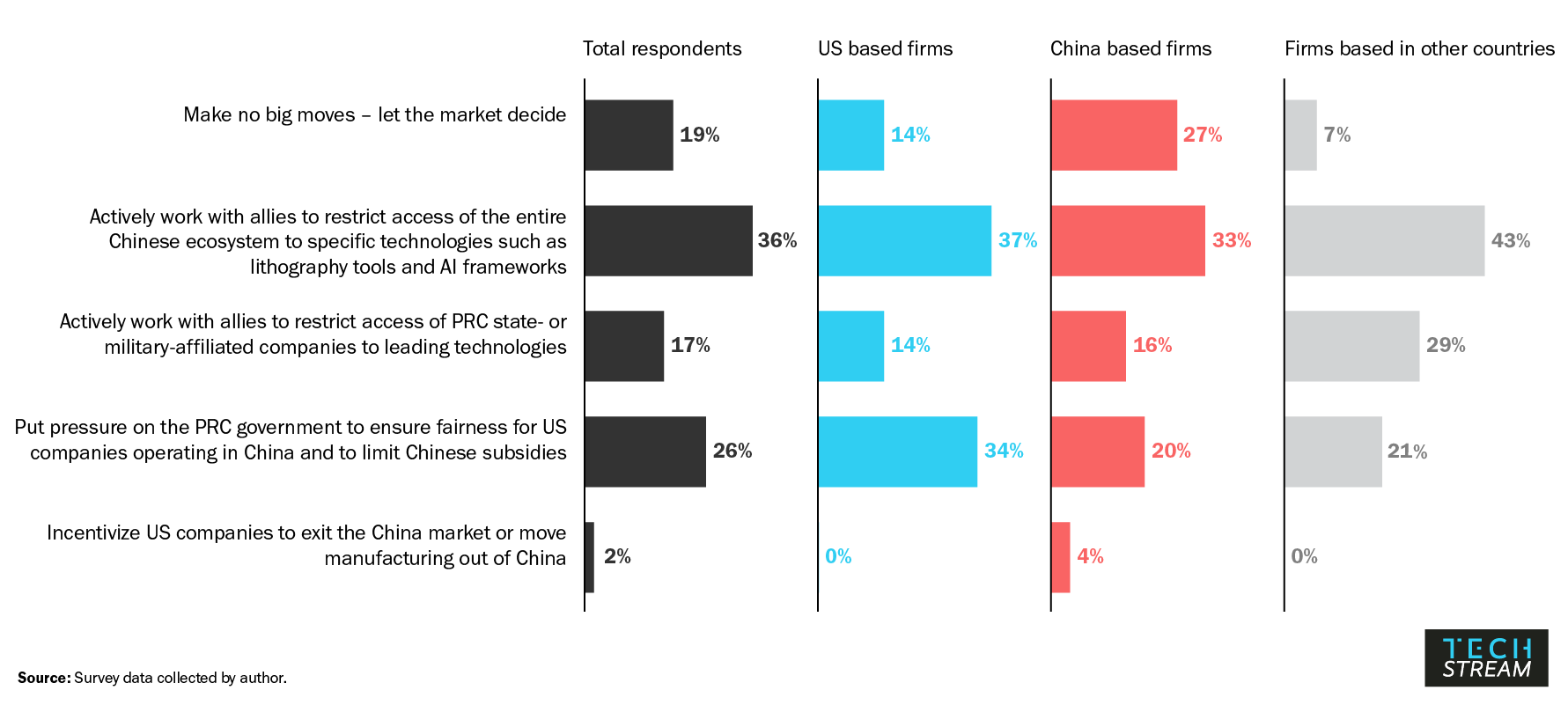

We also asked for suggestions regarding how the U.S. government should modify its policies toward engagement with the Chinese technology industry. Respondents agreed that a proactive U.S. policy approach is necessary, with less than 20% suggesting a hands-off, “let the market decide” approach. One in two indicate that the United States should work with allies to restrict access of the entire Chinese ecosystem to key leading technologies. Despite near universal belief that non-Chinese companies face an unfair environment in China, only 1 in 3 urged the U.S. government to make fixing that a priority. Respondents from China-HQ’ed companies were more likely to suggest a “hands-off” approach—but, intriguingly, were just as supportive of restrictions on technology transfer.

Figure 15: What is the top action the US government should take to deal with the challenge from the Chinese technology industry?

The competitive battleground: separate, blurrily overlapping ecosystems

The future evolution of the global technology industry is often discussed as if it will be determined solely by government policy. Yet the entities that actually design next generation systems, deliver emerging technology solutions, code advanced software, run high-tech fabs, formulate electronic material recipes, and design state-of-the-art chips will collectively determine the outcome. As U.S. policymakers evaluate how to move forward regarding technology policy and China, they will have to accept certain hard realities. Lured by the sheer size of the Chinese market, U.S. companies will aim to compete there—as will competitors from Europe, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and other advanced nations.

At the same time, Chinese policymakers will be limited in their options, as the likelihood of substantial and defensible technology independence is unattainable in the near-term and a longshot in the long-term. Chinese companies intending to sell solutions and services at scale and globally will still need to procure technology from global leaders, and many of those global leaders will likely be American companies. Major Chinese companies will face complex obstacles in building domestic supply chains for goods destined for the Chinese market—in parallel to a global supply chain for products for the rest of the world. Efforts by the government to limit the supply choices of Chinese companies lessen the competitiveness of these Chinese firms in global markets.

With this realization, the U.S. government could consider an approach that combines toughness and attraction. Such a policy would involve targeted technology transfer barriers for a limited number of leading technologies applied to firms with clear ties to PRC military or security interests, strengthened intellectual property protections for U.S. companies both at home and abroad, and nose-to-nose negotiations on Chinese home market access. At the same time, rather than motivating American and global tech companies not to do business with China at all, the new administration might consider shaping the inevitable business collaboration between Chinese and American firms to the advantage of the U.S. technology ecosystem. In other words: Promote American technology in global markets; don’t just protect it. And if openness to global talent, capital, and companies is to the advantage of the United States, then the Biden administration might consider doubling down on attracting those companies and countries that adhere to the transparent rules and norms of the American sphere. This could include those Chinese companies that aim to go global and can commit to doing so while using American-sourced technologies and protecting American-sourced innovation.

These policies must comprehend that these same Chinese companies generally will aim to enable and support a domestic, controllable supply chain as a backup plan. These efforts will receive strong support from the Chinese state. Chinese customers will be less incentivized to go local if American suppliers are innovating faster and delivering better technologies than local PRC alternatives. So while U.S. government policies that backstop American suppliers by pushing for a more level playing field and providing more tools to protect at-risk intellectual property can help, strengthening the innovation environment at home will also matter greatly. And universally in our survey, tech executives believe that openness to global talent and global companies strengthens that home-grown innovation engine.

Technology is an ecosystem game. Winning means aligning a set of companies and engineers around key technologies, maximizing investment to those technology themes and delivering an end-to-end value proposition that is better and has better economics than the alternatives. U.S. policies will be unlikely to convince the CCP not to pursue building a Chinese-dominated tech ecosystem and will be unlikely to convince multinational companies to avoid investing in such a Chinese ecosystem. Boundaries between the U.S. and Chinese ecosystems will be blurry, sharing certain supply chains, companies, standards, and technologies. This makes crafting bright-line policies that limit the success of the Chinese sphere difficult. Policies that mold the right environment for the U.S. technology ecosystem to thrive, while attracting as many global adherents as possible to that ecosystem, needs to be the core objective of U.S. policy. An American ecosystem that convinces the appropriate elements from China (such as globally-oriented technical talent or systems providers keen to win globally) to join the U.S. efforts will likely outperform one that completely excludes Chinese capital and talent. Defining and executing a policy to support such an open approach while protecting American IP, promoting a level playing field, and discouraging the misuse or theft of American technologies will be one of the defining challenges of the Biden administration.

Christopher A. Thomas is a nonresident senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings, a board director at Velodyne LIDAR, and a visiting professor at Tsinghua University. He is also affiliated with the Brookings Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative.

Xue (Xander) Wu is a startup advisor to open source software companies and an alumnus of Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Amazon, Microsoft, and Google provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How global tech executives view U.S.-China tech competition

February 25, 2021