The scandal engulfing the Volkswagen Group goes well beyond Germany, and even beyond the European Union. The fact that the car group managers were able to cheat on emission tests on 11 million cars in multiple countries calls into question public powers’ ability to regulate industry and services globally. The notion that regulatory and supervisory capacity lies at the heart of a well-functioning global economy embodies the real bone of contention in the two major trade agreements under negotiation: the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Those two agreements, if successful, will form the legal platform of the global economy of the future.

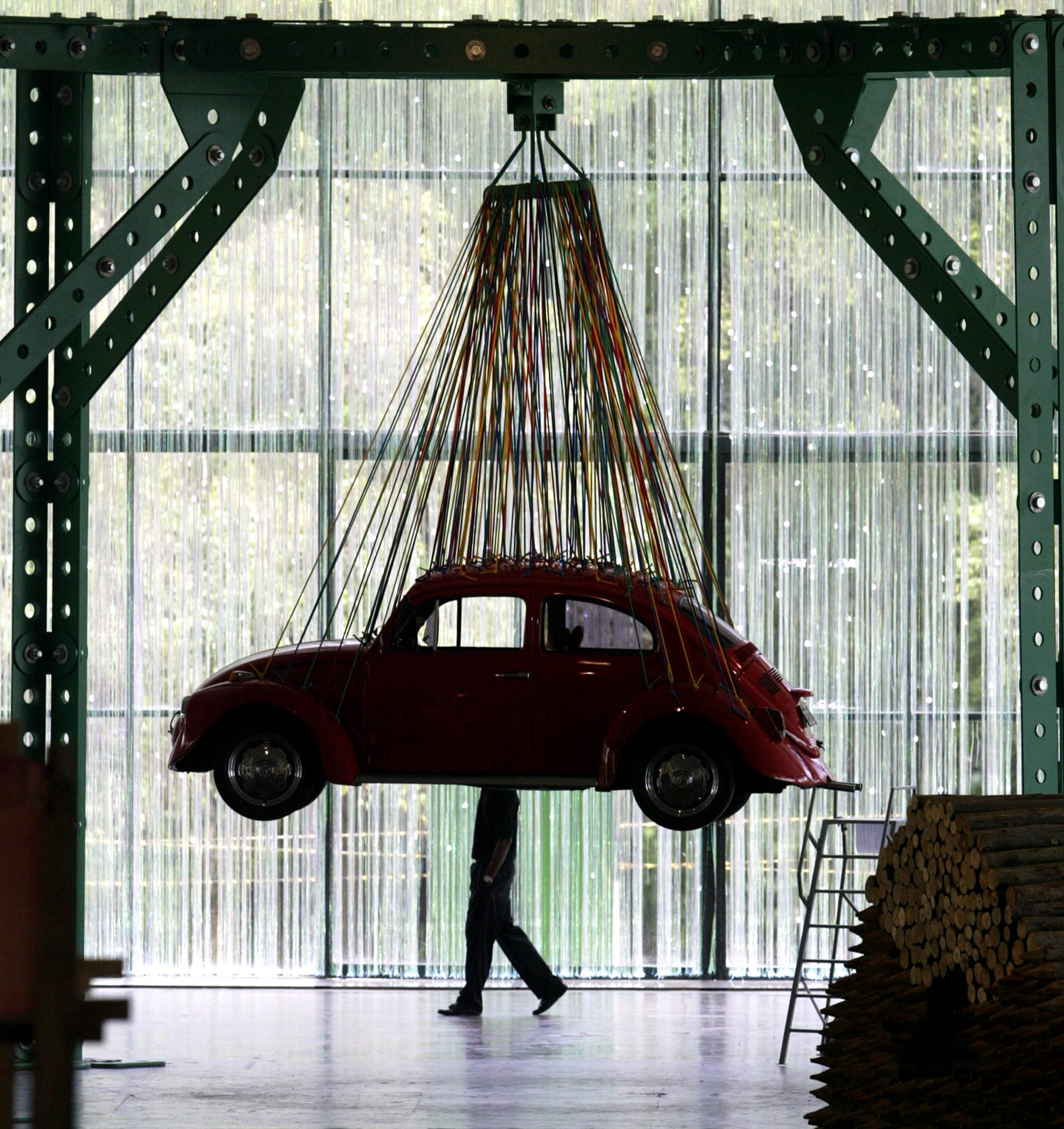

The Volkswagen scandal hangs over European regulators. (Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Paul Whitaker)

The Volkswagen scandal hangs over European regulators. (Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Paul Whitaker)

Losing the moral high ground

Until a week ago, the European negotiators involved in the TTIP negotiations with American colleagues could claim the moral high ground. Europeans generally charge American regulators with being less aware of the need for environmental protection and public health concerns. At the same time, they accuse the Americans of being more inclined to raise invisible barriers to trade through a myriad of standards and sometimes dubious procedures organized in different ways in the 50 states.

After a scandal centered around the largest European automotive group, everything could change. Not only does it call the supposedly morally superior position of the Europeans into question, but it was discovered through a regulatory verification process in the United States. In the TTIP negotiations, regulatory standards are probably the most controversial issue. While Europeans may indulge in a host of conspiracy theories to deflect responsibility, the scandal’s consequence is already established: The European system of regulation and supervision was flawed, and so the American system had to address the problem.

The Volkswagen affair reveals yet again the endemic weakness of the EU regulatory system. Namely, the fact that the common rules are applied in many fields by the national authorities, without any direct power of the “supranational” European Commission to control and sanction. It is for the commission, in fact, to verify the integrity of national control systems—but the issue is so politically sensitive that the controls are often softened. In the case of the car industry, in particular, German automotive lobby was so powerful—both at home and in Brussels—that it inhibited the controls.

The failures of a bifurcated system

There are various examples of the toothless bite of European supervision powers, dwarfed by national governments and lobbies. The most blatant was probably the outbreak of mad cow disease. The English authorities closed their eyes to the local food industry practices, namely feeding cattle with animal protein to accelerate their growth. The European Commission was only able to intervene after the damages became intolerably high.

The recent reform of financial market regulation arose for similar reasons: National regulators applied European rules unevenly to protect the national financial industry, and they were eager to hide the banks’ flaws rather than counter them. Notoriously, the parlous state of European banks in Germany, France, and the Netherlands arose from the flaws and even complicity of national supervisors; this was a major factor behind the euro crisis. Strong national bias in financial supervisory bodies continues to taint the European system of banking supervision, even after recent reforms. Indeed, Germany even managed to exclude a large chunk of its local banking system from common European supervision.

The Volkswagen affair reveals yet again the endemic weakness of the EU regulatory system.

For all the flaws of American regulatory culture, the outcomes of European regulation don’t match the rhetoric extolling the strength of business controls in Europe. Germany led the way in Europe’s global struggle to impose stricter environmental rules. The very fact that Volkswagen, the largest German industrial firm, cheated on emission tests undermines the entire European position. In fact, environmental protection, so important among European regulatory policies, remains an area of traditional national regulation, where no direct common European controls apply.

In the late 1990s, the EU and the United States signed a number of agreements on mutual recognition of testing systems for market access of chemical and pharmaceutical products. U.S. authorities demanded, however, to verify the quality of testing systems in Europe. It turned out that some countries, including Italy, were definitely sub-standard and were then forced to conform.

TTIP vs. TPP: Race to the finish line

All this will severely affect the European position in the TTIP negotiations. The sudden shift in the balance of power could make it even harder than it already is to reach an agreement before the end of the Obama presidency.

The problematic consequence is that a transatlantic agreement will follow, rather than precede, the parallel negotiation that the Americans are conducting with Pacific countries. While Europe has managed so far to sign a bilateral trade agreement only with Vietnam, the United States can close a deal with the entire Pacific basin, excluding China, establishing a new trade platform that will influence all future agreements. Inevitably, it will be the TPP that determines purpose and scopes of regulations and supervisory procedures. All this may end up as a fact on the table at the negotiations with Brussels.

All this will severely affect the European position in the TTIP negotiations.

Originally, the grand strategy of the two transoceanic treaties was exactly the opposite. In one of her last speeches as secretary of state, Hillary Clinton spelled this out very clearly. According to Clinton, Europe and the United States needed to reach an agreement quickly so as to constitute the critical mass necessary for their regulatory standards to spread globally. It was, Clinton said, probably the last opportunity for the Western democracies to establish their influence on the future of the global economy. The euro crisis, which erupted in 2008 and deepened in 2011, has absorbed all of European policymakers’ energy in the following years. It also completely distracted the European Commission—which has exclusive jurisdiction in matters of international trade—from advancing in the transatlantic negotiations.

Political and economic fallout

Now it is probably too late. Issues such as environmental regulation, the protection of individual rights, privacy, and many others, will be determined by the United States and the Pacific basin countries. In the best of cases, the United States will emerge as the “world super-regulator.” Even today, the rules on dealing with corruption are applied by U.S. authorities, even when they concern extra-territorial crimes. Until a decade ago, by contrast, German law explicitly authorized bribes paid abroad by German firms.

The culture of independent regulation has struggled to take root in Europe, where national systems tend to privilege protectionism and corporatist practices. The problem does not arise in those fields where European law and authorities are able to work together to control behavior and impose direct sanctions. This is the case with antitrust policy and with state aid abuses that distort competition, as well as, eventually, with banking supervision.

Once again, the European delays in sharing sovereignty are causing enormous damage to Europe’s economy and to its citizens. This may even sideline the vaunted European sensitivity to environmental protection, food safety, individual rights, and other important features of the European cultural legacy. Europe risks slipping into the second rank in the future global system of economic regulation.

Commentary

Hanging by a thread: Volkswagen and European regulation

September 28, 2015