GERMAN LESSONS

Thirty years after the end of history: Elements of an education

By Constanze Stelzenmüller

When the revolution happened, I was not there for it. To be exact, I was 3,776 miles away in Somerville, Massachusetts. On the clear, chilly afternoon of November 9, 1989, I was sitting at my desk in the drafty wooden double-decker house whose upper-level apartment I shared with three other graduate students, mulling over an early chapter of my doctoral thesis on direct democracy in America. Hunched over library books on Puritan town meetings, I clasped a mug of steaming tea, swaddled in scarf and sweater, and beneath it all, very probably wearing my L.L. Bean double-layered thermal long underwear, essential for survival in a New England winter.

The house phone rang, and continued to ring insistently. It was another West German student. We were used to ribbing each other about our politics, hers crisply conservative, mine vaguely liberal. She said, without preface: “Turn on the TV, the wall is gone.” Annoyed that I’d lost my train of thought, I retorted grumpily that she’d have to be more creative if she wanted to play one of her right-wing political jokes on me. She merely repeated: “Turn. On. The. TV.” Shocked, I did as I was told, and stared in disbelief at the inconceivable, the impossible: fuzzy shots, in grainy black and white, of tens of thousands of people waving sledgehammers and champagne bottles, dancing and singing — on top of the Berlin Wall, for 28 years one of the most deadly borders on the planet. Many people were chanting “Wir sind das Volk,” we are the people.

Direct democracy in action, live — and in Germany.

Then, to my surprise, I burst into tears.

At the end of World War I, one of my grandfathers was a 22-year-old private in the German Imperial Army, while the other was a 19-year-old petty officer on a submarine. As World War II drew to a close, my father was 17, a very relieved and grateful American prisoner-of-war. In the closing months of the Cold War, I was a graduate student in the United States. Officially, I was writing a doctoral thesis, but my hope was to stay, reinvent myself in the great American tradition, and escape the baggage of my German heritage for good. I was all of 27.

War, despair, defeat, and shame had schooled the generations of my grandparents and parents before they ever had a chance to set foot in a place of higher learning. I, in stark contrast, had contrived to string out my adolescence through two university degrees and now a third. As the daughter of a West German diplomat, I was worldly in some ways and laughably callow in others. My real education began (as I was to appreciate later and very gradually) in 1989.

So I can make no claim to shed new light on the events of 30 years ago, on their causes, on their interpretation, or on their lasting effects. I leave that to the politicians who were there and made decisions, or the historians who have studied the files and interviewed participants. Others were agents or observers of history in those heady weeks and months. I was very much its object: thrilled, but very confused.

Instead, this is a frankly subjective and fragmentary look at what I began to learn in that year, and in the three decades thereafter: first as a journalist, and later as a think tanker. I had a great deal of catching up to do. The lessons in store were not small, nor were the topics: war, peace, and memory, prosperity and inequality, democracy and transformation, freedom and identity.

In that sense at least, I may be representative of my generation of West Germans, for whom the miracle of November 9, 1989 — what Timothy Garton Ash has called “that night of wonders, [which] changed everything forever: in Berlin, Germany, Europe, the world” — was mostly an unearned gift. A gift that we have tried, for the past three decades, to understand and live up to as it unfolded around us.

Walls, it seems, are making a worldwide comeback.

Today, that seems more urgent than ever: with a White House bent on disrupting the post-Cold War order, a surging China asserting itself as a power player in the trans-Atlantic space, a Russian president crowing that the liberal idea “has outlived its purpose,” and a deeply divided and fearful Europe looking at a proxy war in Ukraine and growing turmoil in the Middle East and North Africa. Populism is rocking Western societies everywhere. In Germany, the hard right calls the country’s constitutional order “illegitimate.” Walls, it seems, are making a worldwide comeback.

1989: Ends / Beginnings

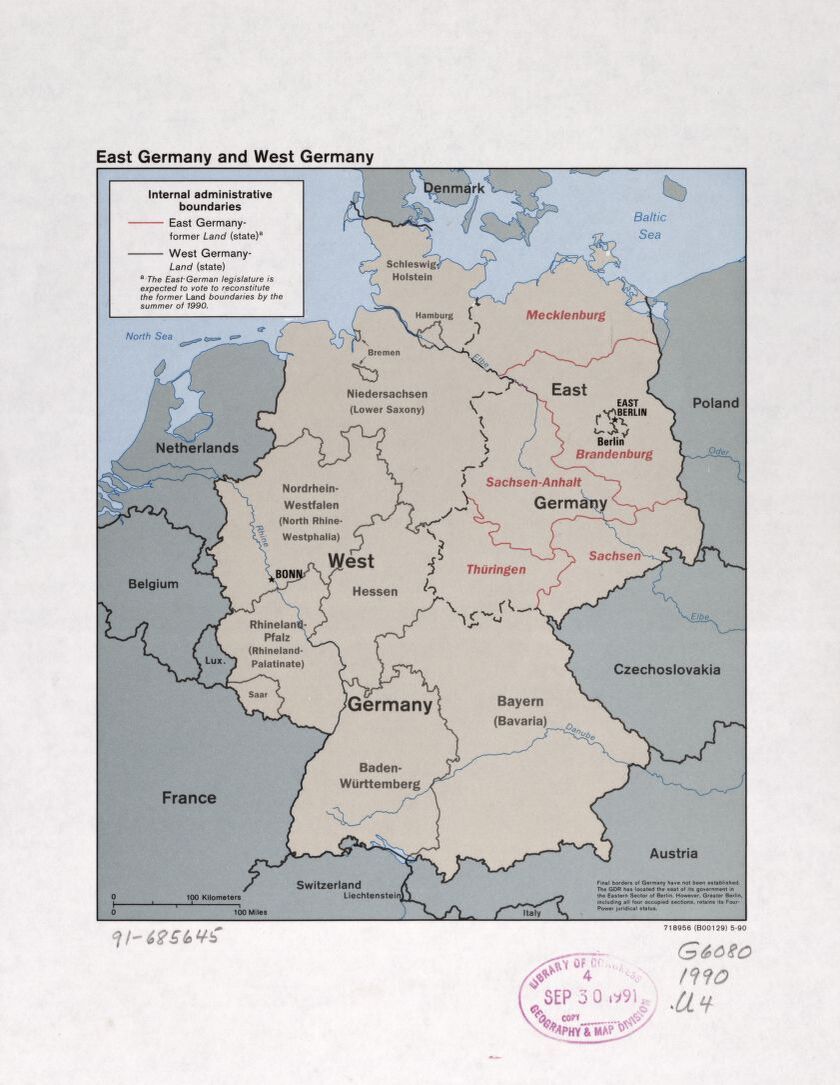

For my generation of West Germans, the wall had been an eternal fixture of our lives. We had never known our country any other way than hacked in two by an 866-mile long frontier of high metal fences fortified with barbed wire, mines, booby-traps, and 50,000 heavily armed guards, from the Baltic Sea to what was then still Czechoslovakia. This “inner-German frontier” was itself part of the Iron Curtain, the 4,300-mile boundary that cut off the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the Warsaw Pact from Western Europe, reaching from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea. The actual wall — a 97-mile-long double concrete barrier punctuated with guard towers and the so-called “death strip” (fitted with trip-wire machine guns, guard dog runs, and trenches) in the middle — surrounded West Berlin, turning it into a Western enclave in the middle of East Germany, known formally as the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

It had been built because by the early 1960s, nearly three-and-a-half million people, some 20% of the population, of communist-ruled and Soviet-occupied East Germany had circumvented emigration restrictions and fled to the West via the then still-permissive border through Berlin. On June 15, 1961, Chairman of the State Council of the GDR Walter Ulbricht told an international press conference in his high, reedy voice: “Niemand hat die Absicht, eine Mauer zu errichten.” No one has the intention of building a wall. On midnight of Saturday, August 12, 1961, the border between West and East Berlin was closed off with barbed wire. Construction began the next morning.

In the nearly three decades that followed, some 75,000 people who attempted to escape from East Germany to the West were caught and punished for the crime of “Republikflucht,” deserting the republic. More than 5,000 East Germans successfully defected to West Berlin. An estimated 140 people died attempting to cross the Berlin wall, whether by jumping out of buildings or trains, swimming through the Spree river, trying to climb over the fortifications, or flying over them in a balloon; most were shot by border guards. Hundreds more died along the inner-German border, or trying to escape across the Baltic Sea.

The wall was, of course, much more than a mere physical barrier. For one, it was a potent symbol of the post-war superpower standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, a reminder that should the Cold War ever turn hot, Germany — both Germanies — would be its central, most lethal battlefield. It was assumed that after a few weeks of conventional warfare, the hostilities would turn nuclear, reducing our country to a smoking field of ashes. Even more importantly, the wall was a punishment. It was an implacable, everlasting reminder of the crimes perpetrated in the Holocaust. In my mind, images of the wall were always superimposed with images of other fences, guard towers, and barbed wire: Auschwitz, Bełżec, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Chełmno, Majdanek, Mauthausen, Sobibór, Treblinka, and many others. Memorials of unforgivable evil.

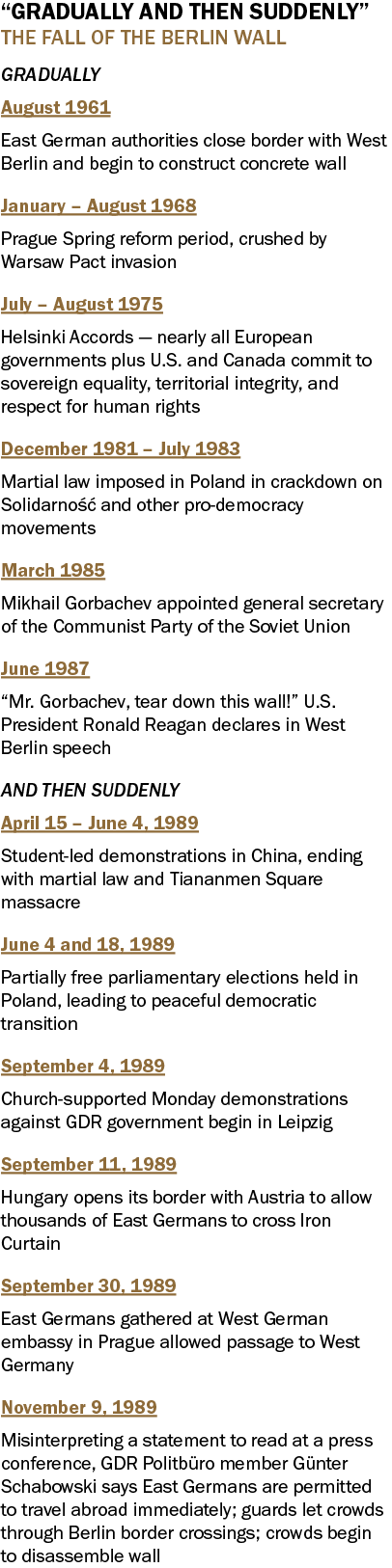

When the Berlin Wall fell, it did so — in the words of the historian Mary Elise Sarotte (quoting a phrase coined by Ernest Hemingway about bankruptcy) — “gradually and then suddenly.”

The gradual part came in the form of “many circumstances and events, both major and minor,” as Serbian diplomat and democracy activist Ivan Vejvoda wrote in 2014: the protesters in East Germany in 1953, in Hungary in 1956, in Czechoslovakia in 1968, and in Poland in 1981; the Helsinki Accords of 1975; and the appearance of a new leader at the helm of the Soviet Union in 1985, who began relinquishing Moscow’s grip on the Soviet satellite countries. “This led to cascading openings — the shredding of authoritarian structures, the progressive espousal of democratic political institutions, and the gradual evolution of market economies based on the rule of law — in Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania.” Vejvoda adds that Western political, economic, and military pressure — not least President Ronald Reagan’s escalation of the Cold War arms race and his entreaty “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” — contributed significantly to the build-up of pressure along the geopolitical fault line of the Iron Curtain.

The sudden part began in the early evening of November 9, when the Politbüro member Günter Schabowski misinterpreted a statement that he was supposed to read to a press conference, saying East Germans would be permitted to travel abroad “sofort, unverzüglich” — right away, immediately. Politicians in West Berlin and citizens in East Berlin decided to take him at his word. At around 11:30pm, a senior Stasi officer at the Bornholmer Strasse crossing, faced with a huge crowd, told two sentries to open the main gate. The cheering masses swept through. The wall did not actually fall, of course. But thousands of people took pickaxes and hammers to it that very night. That was the beginning of the end of its physical presence. Today, only a few segments remain standing in their original place: an erstwhile symbol of fear now covered in colorful graffiti. The rest, smashed to pieces large and small, has travelled around the globe, from slabs that were airlifted in their entirety to tiny shards transported in the pockets of tourists.

The wall was brought down by the courage and determination of many.

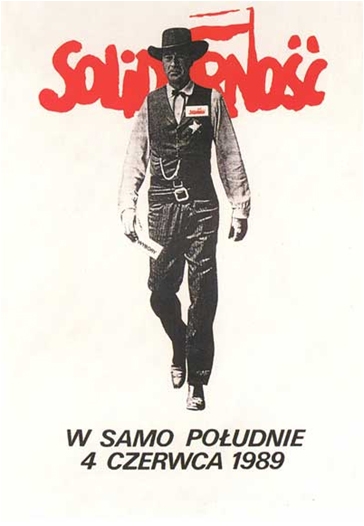

“The principal legacy of 1989,” Vejvoda added, “is one of the resilience and courage of individuals and whole societies.” The wall was brought down by the courage and determination of many: the shipbuilders and steelworkers of the Polish Solidarność movement; Hungarian and Czech activists; Russian dissidents; East German church congregations; and finally the tens of thousands who marched, candles in their hands, in Leipzig each Monday from September 4 onwards; the East German security forces who did not shoot at them; their leaders who did not give orders to shoot; and many multitudes of others. Not a few West Germans had pitched in, writing letters to prison directors in the USSR, or smuggling printers’ ink into Poland and dissidents’ letters out of Moscow. Some later became my friends. To my regret, I was not one of them at the time.

As it happened, I was rather less aware of what lay on the other side of the wall and the Iron Curtain than many other Germans my age. With a father in the foreign service, I had grown up in London, Washington, and Madrid, with only a five-year childhood interlude in Bonn, West Germany’s capital during the Cold War. We had never been posted to the Eastern Bloc, nor did we have relatives in East Germany. Given my father’s job, my crossing into Warsaw Pact territory as a curious tourist was out of the question; I would have been an easy intelligence target. So the half of Europe that lay east of the inner-German border was a blank space on my mental map. For me, Dresden was at least as far away as Arkhangelsk.

To ignorance I added, alas, indifference. My liberal parents were proud that German chancellor Willy Brandt had signed the Warsaw Treaty (which accepted the post-war border demarcations between Germany and Poland) on December 7, 1970 and revered him for having gone to his knees to beg forgiveness in the Warsaw Ghetto on the same day. Many people who voted right-of-center (my maternal grandparents included) considered him a traitor for the same reasons. Some of the most vocal and unrepentant among these critics were representatives of the associations of ethnic German deportees who had been driven westwards from Eastern Europe. I was disgusted by many conservatives’ utter lack of empathy for the victims of Nazi Germany, and so I saw no need to empathize with their losses. As far as I was concerned, the Warsaw Pact was welcome to all of it, forever.

The matter of the 16 million Germans living in the GDR was more complicated. At home, my parents left no doubt that we were lucky to be citizens of a democracy, and part of free Europe and the West. But it was common currency in West German left-of-center milieus — this included many of my school teachers and some of my fellow university students — to believe that the Federal Republic was somehow tainted: by permitting many Nazis big and small to escape punishment; by the presence of large numbers of American, British, and French occupation forces; by capitalism and Coca-Cola. Was the Other Germany, so much more spartan and egalitarian, not a better, purer version of us? Much of this struck me as self-serving and wrong, but I also didn’t want to be on the side of the revisionists and their propaganda. And so I remained willfully, shamefully blind to the bleakness and brutality of life on the other side of what the GDR cynically called “the anti-fascist protection rampart” until after it disappeared.

Why then — given that I knew little and believed I cared less — did I burst into tears on November 9? The summer of 1989 had been an eventful one. I had already choked up once in front of the TV on June 4, at the images of the massacre on Tiananmen Square. Yet on the same day, Solidarność — the former underground movement had only been legalized in April — won the elections in Poland, triggering a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe.

Later that summer, my mother fainted on home leave, and was found to have a large brain tumor. She spent the following months in various intensive care units, and I flew back and forth between Boston and Frankfurt to be with the family. We would be at her hospital bedside, bleary-eyed and anxious, each morning at 8am. But my indomitable mother insisted on us reading the news from Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, the Baltics, and finally East Germany to her first thing every day.

My father and mother had, at ages 17 and 11, witnessed the apocalyptic end of the Third Reich, and found themselves alive, quite unexpectedly, to become part of the generation that was to rebuild Germany and Europe. Unlike me, they grasped immediately and passionately what I could only vaguely intuit: how much despair and courage it took to march in the streets, knowing the ruthlessness of the communist regimes, and the terrible odds against success. We were terrified that it would all end in gunshots and bloodshed, like in Beijing.

The tears I shed on seeing those grainy images of the dancers on the wall were sobs of relief, of joy, and of awe. Awe at those East Germans who had stood up with quiet dignity to the threat of overwhelming, ruthless counterforce, who had demanded and taken their freedom without a single act of violence (and notably in the absence of any kind of unified leadership). Who had given Germany — the “belated nation,” as the German philosopher and sociologist Hellmuth Plessner called it, and country of so many failed uprisings and thwarted resistance movements — its first nonviolent and successful grassroots revolution. A lesson that history can have moments of amazing grace.

For my parents’ generation, and by extension for my generation as well, any emotion that purported to attach to country, nation, or people had become inherently suspect.

And why was I so surprised by my own feelings? For my parents’ generation (the children of World War II), and by extension for my generation as well, any emotion that purported to attach to country, nation, or people had become inherently suspect. The very words describing them — Heimat, Nation, Volk — had been rendered toxic by the National Socialists. My shock also marked the release from an emotional prohibition. These were real people, our people, not abstractions, and it was alright to care what happened to them.

That night also transformed the deep ambivalence I had harbored about my own country. After I’d finished high school in Madrid in 1979, I was reluctantly shipped to Bonn for university. Having witnessed firsthand the first three years of Spain’s dramatic transformation from one of Europe’s most backward and poor dictatorships to a vibrant democracy, I thought that my fellow students had very little appreciation of their freedoms, their prosperity, and the general well-orderedness of public affairs. Instead, they seemed paralyzed by the future as much as by their past. Apocalyptic fears of nuclear war, poisoned soils, and dying forests ran rampant. The founders of the far-left Baader-Meinhof terror group were in prison, but their acolytes continued on their killing spree. (The car-bomb assassination of Deutsche Bank’s board speaker Alfred Herrhausen on November 30 is also part of Germany’s 1989.)

In Bonn, government ministries were still protected with steel fences and razor wire, and armored personnel carriers patrolled the streets. My law studies were punctuated by huge demonstrations against the nuclear arms race and the stationing of Pershing II mid-range missiles. At their height — 500,000 in June 1982 — they more than doubled the population of Bonn. The yelling, jostling, and sweating throngs made it quite difficult to navigate to class.

Not that I was eager to get there. I had been appalled to find how many of my law professors preserved a glacial omertà about the entanglement of their own academic fathers in National Socialism, and the indispensable role of the legal profession as architects and enablers of the Third Reich and the Shoah. Many of my fellow students appeared unconcerned about this, but then a lot of the men were members of dueling fraternities, which were notorious for their hidebound conservatism. The filmmaker Margarethe von Trotta had given the era one of its most lasting descriptions when she titled a film based on the life of the Baader-Meinhof terrorist Gudrun Ensslin “Die bleierne Zeit” — A Time of Lead.

The Cold War, the division of Europe, and a parental generation scarred and traumatized by war: that, we believed, was the new forever normal, our fate until old age. Getting a scholarship to Harvard in 1986 was a huge stroke of good luck. I fled to America, hoping to find a way to stay there for good.

And now here I was in Boston three years later, watching incredulously as Berliners from both sides of the “death strip” celebrated the biggest and most raucous family get-together the country had ever seen. If all these Easterners wanted to be with us … maybe there was something to like, or even love, about my country after all.

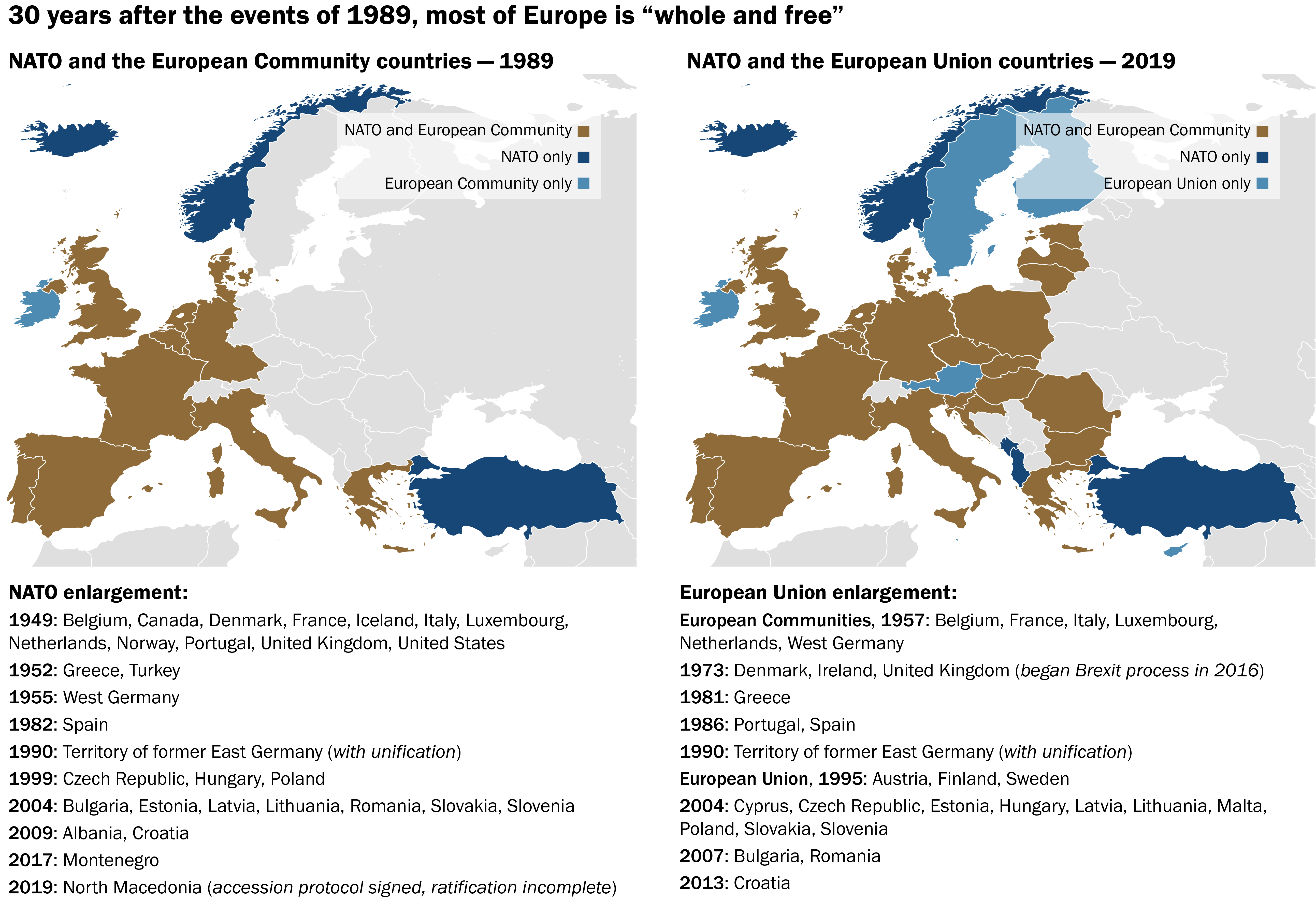

Like 1776 in the United States and 1789 in France, 1989 was to be the foundational moment for a new Germany. And not just Germany. Even then, few dared imagine what the events of those months would unleash. But before the year was out, communist leaders were toppled in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. On October 3, 1990, under the enlightened leadership of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and U.S. President George H.W. Bush (with the consent of the USSR’s leader Mikhail Gorbachev and the deeply reluctant toleration of French President François Mitterrand and U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher), the two Germanies once more became one and fully sovereign. In November 1990, most European governments, the United States, Canada, and the Soviet Union signed the Charter of Paris, which laid the foundation for the new security architecture of Europe and the creation of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Its preamble declared:

The era of confrontation and division of Europe has ended. We declare that henceforth our relations will be founded on respect and co-operation. Europe is liberating itself from the legacy of the past. The courage of men and women, the strength of the will of the peoples and the power of the ideas of the Helsinki Final Act have opened a new era of democracy, peace and unity in Europe.

In July of 1991, the Warsaw Pact dissolved itself. In September of the same year, the three Baltic Republics achieved independence. By the end of December, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. In 1999, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland become members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); seven more Central and Eastern European countries joined them in 2004. Eight former Warsaw Pact members joined the European Union in 2004, with Romania and Bulgaria following in 2007. Less than two decades after the events of 1989, almost all of Europe was — as President George H.W. Bush had foretold in 1989 — “whole and free.” Today, NATO counts 29 members (30 once North Macedonia joins), and the European Union 28 (still including the United Kingdom).

So the toppling of the Berlin Wall was both consequence and prelude, a part of something much greater: a genuinely European revolution, powerfully heralded by a Polish pope, enabled by the last president of the Soviet Union, and midwifed and nurtured by the United States. Its impact, however, rippled around the world, empowering civil societies to end authoritarian regimes in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. The interpretive consensus of the day was epitomized in Francis Fukuyama’s famous essay “The End of History,” which declared the “total exhaustion of viable systemic alternatives to liberalism” and went on to suggest that this might be “the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

We were the world champions of atonement. We had earned the peace dividend, and we intended to enjoy it.

Nowhere did the theory of the end of history and the victory of the West through democratic transformation and the spread of a rules-based international order find more enthusiastic applause than in Germany. Having been two nervous frontline states for 45 years, we were now an 80-million-citizen powerhouse in the middle of Europe, and — as Defense Minister Volker Rühe put it memorably in 1992 — “encircled by friends.” We were, after all, the world champions of atonement. We had earned the peace dividend, or so we felt, and we intended to enjoy it.

Or, as the diplomat Thomas Bagger noted wryly in his recent essay “The World According to Germany: Reassessing 1989”:

Toward the end of a century marked by having been on the wrong side of history twice, Germany finally found itself on the right side. What had looked impossible, even unthinkable, for decades suddenly seemed to be not just real, but indeed inevitable. …

Best of all, while Germany would still have to transform its new regions in the East, the former GDR, the country in a broader sense had already arrived at its historical destination: it was a stable parliamentary democracy with its own well-tested and respected social market economy. While many other countries around the globe would have to transform, Germany could remain as is, waiting for the others to gradually adhere to its model. It was just a matter of time.

I went back home on December 5, 1989, less than a month after the fall of the wall. I needed to be near my family. But I also wanted to be there for a new chapter of Europe’s history.

2019: Lessons learned / Not learned

Thirty years have now passed since 1989. History, it turned out, did not end that year. Nor did war, inequality, authoritarianism, or great power competition. If anything, they are ramping up fiercely: in the world, and increasingly in Europe, too.

Wars, genocides, and ethnic cleansing in the former member states of Yugoslavia, the African Great Lakes, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Libya, as well as in Georgia and Ukraine — many of which continue to this day — have profoundly challenged the West’s values, and forced it repeatedly to deploy considerable economic or military power, as well as diplomatic capital, to stop the bloodshed and attempt to create conditions for peace. Success, it has to be said, has been mixed at best.

When al-Qaida attacked America on September 11, 2001, it took a swing at the main pillar of the trans-Atlantic alliance, and the liberal international order. The pillar remained standing, but the world saw it tremble. The global financial crisis of 2008, which enriched a few and impoverished many, undercut the liberal consensus on the universal benefits of globalization and morphed into a eurozone crisis which bitterly divided Europe.

Today, the trans-Atlantic alliance as well as the European project are in great disarray and riven by self-doubt.

The 2011 Arab Spring destabilized the Middle East and its turn towards tragedy, particularly in Syria and Libya, escalated Europe’s migration crisis to a new level in 2015, challenging governments and lighting a fuse under hard-right, ethno-chauvinist political groups across the West. These groups have deepened Europe’s divisions and raised questions about the viability and legitimacy of representative, pluralist, and open democracies in the modern world. Authoritarians are in power in Hungary and Poland. Illiberal great powers like Russia and China cannily exploit fissures in the West for their own purposes. Today, the transatlantic alliance as well as the European project are in great disarray and riven by self-doubt.

Reunified Germany spent a quarter-century offering excruciatingly slow responses to ever more urgent demands by its neighbors and allies that it exert greater weight in Europe. What The Economist dubbed in 2013 the “reluctant hegemon” woke up the following year: Its president, foreign minister, and defense minister all vowed at the 2014 Munich Security Conference that the Berlin Republic would henceforth assume a responsibility in line with its immensely increased economic power.

But five years later, the national mood has shifted drastically. Once confident and determined, Germans are now nervous and glum. Today, we are no longer George H.W. Bush’s preferred “partner in leadership,” (a partnership that finally came into being with the close cooperation between Barack Obama and Angela Merkel) but Donald Trump’s “bad, very bad” Germany. As the memorandum of a July 2019 phone conversation between Trump and his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelenskiy showed (Trump: “Germany does almost nothing for you.” Zelenskiy: “Yes you are absolutely right.”), other leaders these days attempt to score points by joining in the chorus. Berlin’s relations with many of its European peers have soured. Its economy may be heading for a recession. Chancellor Merkel, in her fourth term, is helming a fractious grand coalition government; she often looks profoundly tired.

Worst of all, the euphoric family reunion of 1989 has become an increasingly bitter dispute about the relationship between Germany’s western and eastern states. A nationwide poll in January 2019 showed that 52% of east Germans (as opposed to only 26% of west Germans) thought that their regional origin still set them apart. In exit surveys conducted for the September 1 regional elections in the eastern states of Brandenburg and Saxony, 59% and 66% of those polled, respectively, agreed that “East Germans are second-class citizens.” The hard-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) plays on these grievances expertly. In a cynical reprise of the vocabulary of the demonstrations of 30 years ago, it calls on east German voters to “resist” (suggesting they are still living in a dictatorship), and urges them to “Vollende die Wende!,” complete the revolution. Even Chancellor Angela Merkel (an East German herself) had to acknowledge the deep divide in an October 3 speech on the 29th anniversary of reunification. “We have to learn to understand that, and why, reunification was not an unequivocally positive experience for many people in the eastern German states.”

As for myself, after turning in my dissertation, I interned at a daily newspaper in Berlin and then went on to a national weekly. In the early 1990s, I wrote about the trials of Stasi officials and a village in Brandenburg where arsonists had burned down a refugee hostel. Later, I reported on German military deployments, from Belet Huen in Somalia to Kunduz in northeastern Afghanistan. I wandered silently through the blood-spattered cells of a Jesuit monastery in Kigali in July 1994 and witnessed the uncovering of mass graves on the green shores of Lake Kivu a year later. I interviewed former student leaders of the Tiananmen Square uprising who had found asylum in the U.S., as well as covered the first Yugoslav war crimes tribunals in The Hague and the final diplomatic negotiations for the International Criminal Court.

I marvel at this miracle of resilience, peace, and prosperity that has grown out of the ruins of two world wars.

But it was my think tank career that finally took me into Eastern Europe. Unforgettable: my first trip to Warsaw, which Hitler’s Third Reich (with help from the Soviets) had tried to erase from the face of the earth, lovingly rebuilt by patriotic Poles. Countless trips across the European Union later, and with many new friends, I’m profoundly aware of all we Europeans disagree about — and how weak that makes us look. Yet I marvel at this miracle of resilience, peace, and prosperity that has grown out of the ruins of two world wars, and which has been protected and nourished by NATO and the EU. When I finally returned to the United States, a quarter-century after leaving Boston, it appeared comfortably familiar; I was certain I knew my own country. On both counts, new and painful lessons were in store.

My parents are dead now. Yet I understand much more intimately today why they were so determined to shelter their children from harm. I have met war criminals and victims, traumatized soldiers and terrified civilians, unsung heroes and dedicated, honorable politicians. I’ve interviewed people who were later murdered. I too now have memories that are hard to talk about, but they are a part of who I have become. Some of my teachers, mentors, role models, and friends are no longer alive. I miss the light and warmth they shed around them, and on the path ahead.

My education turned out to be more thorough than I could ever have imagined back on that crisp November afternoon, staring at the grainy TV. But what have I learned?

War, peace, and memory. The fact that I am not the descendant of war criminals is pure luck. One of my grandfathers died in 1937. The other, an electrical engineer, was too old for service in World War II. My father was drafted at 16 in 1944, out of a Protestant boarding school that disapproved of the Nazis and saw little action before turning himself in to an American GI. He and his peers were left standing in the debris with a deep contempt for those who had lied to them and tried to send them to their deaths. Unlike many older Germans, my parents had nothing to hide and we children did not have to distrust or despise them. In fact, they — and most of our schoolteachers — were very clear about the enormity of German guilt.

Initially, of course, West Germans did not willingly embark on a national atonement for the crimes of the Third Reich; they were forced to do so by allied war crimes tribunals. It took another generation for my country to conduct its own trials, and to acknowledge just how many ordinary Germans had been complicit, whether it was by buying the business of the Cohns next door, ignoring their sudden disappearance, or acquiring their left-behind household possessions at startlingly low auction prices. It took 70 years after the beginning of World War II — and the work of a multitude of scholars, journalists, and citizens’ initiatives — to achieve a full accounting of our catastrophic 20th-century history.

In communist East Germany, in contrast, the state ordained an official historical doctrine according to which all the Nazis not killed in the war had miraculously stayed in the Western part of the divided country. This “amnesia,” as the author Ines Geipel (once a star GDR track runner and the daughter of a high Stasi official) has pointed out, worked both ways for the communist leadership: It let them “gag the populace about National Socialism, and constrained the returnees from exile in Moscow to remain mute about Stalinist terror ... a secret pact that exonerated and served as a basis for coming purges.” She lists the price of this oblivion:

300,000 political prisoners, 75,000 imprisoned for attempting to flee, hundreds killed at the wall, 4.6 million who fled to the West between 1945 and 1990, more than four million deportees stranded in the East, 2 million subjected to forced collectivization of agriculture, 120,000 survivors of special NKVD [People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs] camps, tens of thousands deported to the Soviet Union, nearly half a million deprived of their childhoods in orphanages, and more.

Younger East German authors have written forcefully and movingly about the post-1989 consequences of this psychological and moral devastation. The journalist Daniel Schulz, born in Potsdam in 1979, reminds his readers that neo-Nazis who terrorized rural areas and defaced Jewish gravestones with swastikas existed even in the GDR. The Stasi made light of them as unpolitical “rowdies” or as “provocations from West Germany,” whereas they cracked down brutally on punks as emissaries of “Western decadence.” He describes his own immersion into a local skinhead tribe as part of a general unraveling of state and society: “Violence was normal and in this normalcy the Nazis swam like the fish in the sea.” Yet — with the exception of the xenophobic riots of Hoyerswerda and Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1991 and 1992, which made international headlines — the rest of the country seemed to shrug off this explosion of lawlessness. (As a newspaper intern in Berlin, I was once sent to cover a neo-Nazi trial in Frankfurt an der Oder, close to the Polish border. The sullen insolence of the young thugs on the stand made a lasting impression. As did having to dive for safety after the trial, when neo-Nazi skinheads and Antifa went for each other with baseball bats outside the courthouse.)

This toxic historical groundwater is now helping the AfD garner alarming support, winning one-quarter or more of the vote in recent regional elections in eastern Germany. But while the hard-right party has been plateauing at around 10% in the western regions of Germany, that is also where its intellectual roots are oldest and strongest, as the historian Volker Weiß has documented. The AfD’s leadership is almost exclusively from the west, leading the writer Christian Bangel, a native of Frankfurt an der Oder, to warn: “It is hypocritical to treat the East as the hazardous waste deposit of woke Germany. And dangerous. Because the East is Germany’s great political innovator.” We westerners may have accounted for our 20th-century history of right-wing extremism, yet we manifestly struggle with its modern versions. We have no cause whatsoever to be smug.

and then-Lithuanian President

Dalia Grybauskaitė visit German NATO troops deployed in Lithuania.

(Ints Kalnins/Reuters)

Other lessons from history were arguably over-learned. Post-war West Germany was so deeply pacifist (its Basic Law of 1949 did not even provide for armed forces) that when it had to stand up 12 divisions (250,000 troops) to become a NATO member in 1955, there were riots. Today, Germany has soldiers stationed in the Baltics, in the Balkans, in Africa, on the Mediterranean, in Iraq, and in Afghanistan, but it struggles to keep up with its defense spending commitments. As the German Marshall Fund’s Jan Techau observes: “Germany’s supply-side develops slower than the world’s demand side.”

But as I saw firsthand as a journalist in conflict zones, the deployment of military force can stop wars and war crimes. I am convinced that the Rwandan genocide could have been prevented — like much of the killing in the Balkans, or the current bloodshed in Syria — with earlier, decisive action. (And for what it’s worth, liberating Afghanistan from the Taliban and Libya from Moammar Gadhafi saved many thousands of innocent lives.) The officers and soldiers who took on new and unfamiliar roles in these operations, and often had to improvise on the basis of imperfect political guidance, deserve immense respect. Yet it continues to dismay how little policymakers truly know about the environments in which they intervene, how bad they are at explaining their actions to their publics, how ineffectual they are at implementing plans, and how little responsibility is taken for unintended consequences. And certainly the West’s record of creating peace is patchy at best.

There is no such thing as an easy war, or a simple victory.

In this new era of great-power competition, a fractured West is focusing on deterrence again, as well as on national and alliance defense. “Out-of-area” operations have gone out of fashion. Yet we cannot escape the dilemmas of humanitarian intervention or post-conflict stabilization, although we may have to be more pragmatic about what kind of stability is achievable. Indeed, I believe there are necessary wars, and just wars. But there is no such thing as an easy war, or a simple victory.

Prosperity and inequality. The post-war transatlantic alliance began with food. In the first two years after World War II, harsh winters, hunger, and deprivation killed millions more people in Europe and the Soviet Union, one of my great-grandfathers among them. It was U.S. food aid, and then the Marshall Plan and American stewardship of a liberal international trading order that enabled the reconstruction and democratic revival of Europe — or rather of Western Europe, since Stalin’s Russia prohibited Eastern Bloc countries from accepting U.S. aid. The “Luftbrücke,” or air bridge, with which allied planes supplied food and coal to West Berliners during the 1948-49 Soviet blockade remains unforgotten in Germany’s capital. Ordinary Americans, too, sent hundreds of millions of CARE (Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe) food packages to recipients overseas until the early 1960s. Their arrival was a major event, including in my mother’s family. My 17-year-old POW dad was delighted by American canteen food. But having to be grateful also made people resentful, as my grandmother’s begging letters to overseas acquaintances from the late 1940s show. Yet over time, the roaring growth and deepening economic integration of the economies on both sides of the Atlantic became a pillar of the U.S.-European relationship. For all these reasons, the fact that the Trump administration is now slapping tariffs on its allies as much as on its adversaries — in effect weaponizing that interdependence — hits a particularly sensitive nerve.

After 1989, the economic corollary of the “victory of democracy” thesis was the theory of convergence: Market capitalism would inevitably establish itself not just in Europe but around the world. This, in turn, would help consolidate freedom and democracy globally. But 30 years later, that notion has been falsified in multiple ways, notwithstanding the fact that free-market therapies helped formerly communist economies modernize and grow, and lifted tens of millions out of poverty. China is becoming more totalitarian, not less, and its entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, contrary to predictions, did not turn it into a “responsible stakeholder” but into a ruthless abuser of the international trade system. Russia has turned into an authoritarian kleptocracy. Neoliberal prescriptions (the “Washington consensus”) led to the global financial crisis in 2008. In Europe, German fiscal orthodoxies helped turn it into a eurozone crisis.

Did this open the floodgates for the populists? In a new book, Thomas Kleine-Brockhoff argues that for France, the United Kingdom, and the U.S., the answer is yes, because globalization siphoned off jobs and entire industries from these economies, while enriching the wealthy at home. In Northern and Central Europe, in contrast — which still boast full employment, growth, and below-average inequality — populism is not about economics (in Germany, even AfD voters tell pollsters that they see their economic situation as good or excellent), but identity. Of which more shortly.

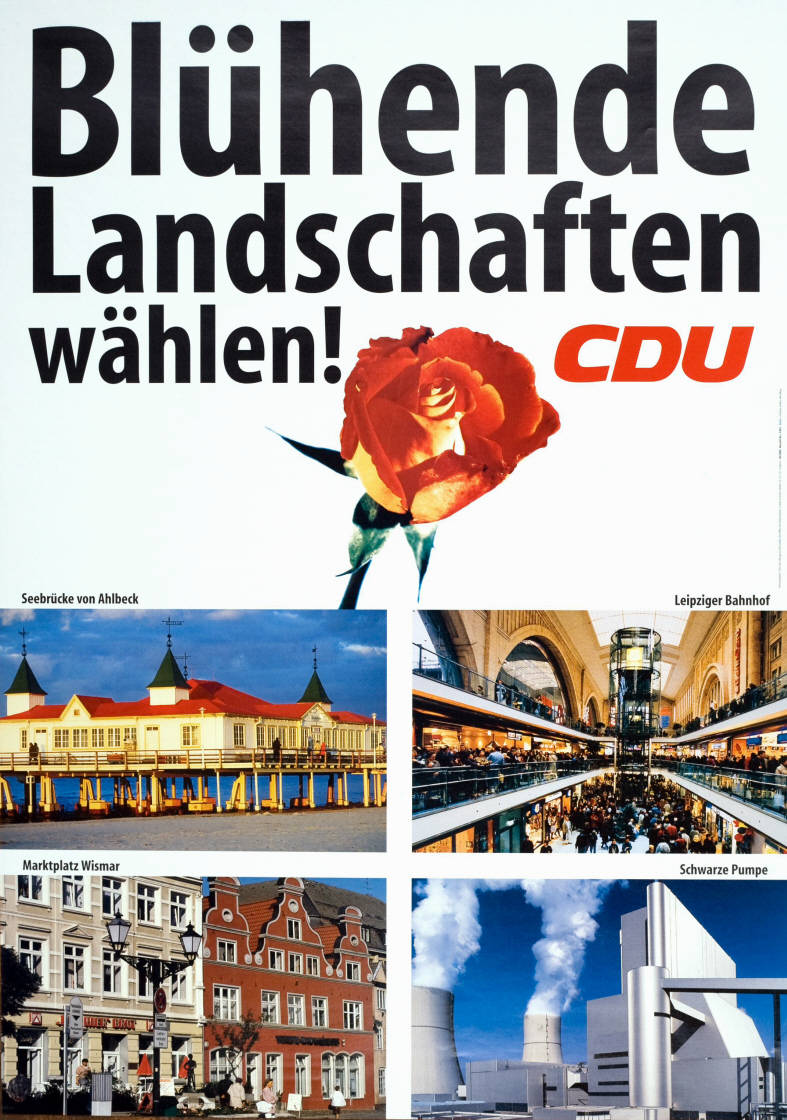

That said, the German story is complicated by the unequal legacy of unification. Months before the fall of the wall, the Stasi wrote a memorandum to explain to the geriatric leadership of the communist state why so many citizens were fleeing to the West: shortages of consumer goods and services, bad workplace conditions, travel restrictions, oppressive living conditions. In 1990, Chancellor Helmut Kohl promised the East Germans “blühende Landschaften,” flourishing landscapes, and the West Germans that none of this would cost them a pfennig.

Twenty years later, Germany’s former finance minister Peer Steinbrück estimated the cost of reunification at two trillion euros, “an average 100 billion euro” per year. The latest annual report compiled by the office of the Commissioner on German Unity records healthy growth rates, record unemployment, and salaries and pensions that have nearly reached west German levels. Environmental disaster zones have been cleaned up, historic cities and towns painstakingly restored. Yet it also points out that no major German company is headquartered in the east. The key reason for the structural lag between the western and eastern parts of the country, however, is the drastic dip in birth rates in the east immediately after 1990, and a net emigration of more than 1.2 million east Germans — often young, well-educated, and female — to the west.

The Treuhandanstalt — the agency created to privatize East Germany’s state-owned enterprises — has come under harsh criticism for closing allegedly profitable businesses; in truth, that was the case for only a handful of companies. As a rookie reporter covering hunger strikes in factories that had been summarily shuttered, I was shocked to encounter plants on the outskirts of Berlin and farther afield that looked like locations for movies set in the 1950s, or the 1850s. The despondent foremen who showed me around acknowledged as much.

What also became heartbreakingly clear in these conversations was that the inevitable economic transformation of eastern Germany was going to bring with it huge personal costs for millions of people whose skills, experience, and achievements were no longer valued. The communist caretaker state was gone. There was also no little amount of west German carpetbagging. While easterners were told they would have to retrain, or accept lower-skilled jobs, many of the new government, academic, and corporate jobs were taken by westerners. This included some of my law school classmates, and not those with the best grades. Meanwhile, easterners are underrepresented (with the notable exception of Chancellor Merkel, who grew up in Brandenburg) among Germany’s elites to this day.

On the evening of March 18, 1990, after the last elections to the East German legislature, the West German Social Democratic parliamentarian Otto Schily was interviewed on national TV and asked to comment on the electoral victory for Helmut Kohl’s Christian Democrats. When he silently drew a banana from his pocket, viewers immediately recognized the insulting implication: The East Germans had voted for fresh produce and consumer goods (rather than for, say, democracy and free speech). The arrogance and disrespect of that gesture resonates to this day. We West Germans — and certainly Schily, who was 12 when Nazi Germany capitulated to the Allies — ought to know all about the connection between hunger, freedom, and dignity.

Democracy and transformation. When I chose in the late 1980s to study direct democracy in the United States, it seemed in keeping with the hopeful spirit of the times: Maybe, just maybe, we Germans could begin to trust ourselves as much as other mature democracies did? But the closer I looked, the clearer it became that the widespread usage of the referendum and initiative at the state and local level had actually undermined and damaged governance in America, regularly disenfranchising weaker, more defenseless groups. Harvard’s Judith Shklar accepted me as a reading and research student and tolerated my topic (with a raised eyebrow) while insisting firmly on the historic civilizational achievement that is liberal democracy as set out by the Framers: representative, limited government, checks and balances, and the protection of minorities against the tyranny of the majority. A blessing whose value she knew only too personally as a Jewish refugee from wartime Riga, first in Canada and then in America. She made me realize just how carefully calibrated is the constitutional architecture drawn up (with American help) in Germany’s Basic Law of 1949.

It has been all the more disturbing to see the rise of illiberal authoritarianism around the world and across Europe. The organization Freedom House has been charting a decline of liberties worldwide since 2005, while the Pew Research Center has been recording an increasing dissatisfaction with democracy. This is true not just for China and Russia, or the post-Arab Spring Middle East, but for Western democracies, which we thought could never fall back behind the achievements of 1989: new democracies like Hungary and Poland, and even old, deeply rooted democracies like the United Kingdom and the United States. And for Germany, which we naively assumed in 1989 would never revert to authoritarian ideas because we had done such a perfect accounting of our sins and built so many safeguards into our system.

It’s been difficult to watch an American president and a British prime minister lathering up crowds of supporters by denigrating the pillars of representative democracy (Congress or the Parliament, the courts, the civil service), trashing its mediating institutions (academia, the press), and slandering the law and the truth — all in the name of “popular will,” and cheered on by Vladimir Putin. The crucial role played by Polish and Hungarian activists in tipping over the domino chain of democratic revolution in 1989, and the debt we Germans owe them, makes the paranoid intransigence of Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of Poland’s ruling right-wing Law and Justice party and the nasty ethno-chauvinism of Hungary’s prime minister Viktor Orbàn particularly hard to bear. (Merkel protected the latter against European censure for years.) Kaczyński and Orbàn are dismantling liberal democracy, while British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Trump appear to be hellbent on exhausting it. The method may be different, but the outcome risks being quite similar.

And Germany? Where a stunning 58% of respondents told pollsters in a recent survey undertaken in Berlin and in the five eastern states that they were no better protected against arbitrary government than before 1989? Where more than a quarter of the voters in three recent eastern regional elections voted for the AfD, which has been visibly and rapidly radicalizing in recent months, and whose leaders have marched at the side of neo-Nazis in violent demonstrations? Where a senior regional politician who had expressed his support for Merkel’s policy of welcoming refugees in the crisis year of 2015 was shot at point-blank range by a known right-wing extremist in Kassel, a western German city notorious for its hard-right scene? And where, on October 9 — the 30th anniversary of the day on which 70,000 people marched through Leipzig with candles in their hands, signaling the beginning of the end for the communist system — a lone gunman tried to shoot up Yom Kippur celebrants in a synagogue in Halle an der Saale, killing two and wounding another?

Has Germany’s contrition, or the democratic transformation of Europe that began in 1989, been no more than a thin veneer that is now beginning to crack? Might Vladimir Putin be right when he argues that liberal democracy has run its course?

Again, the problem is probably more accurately located in our own misguided expectations or our hubris. In America and the U.K., perhaps too much faith has been placed in the ability of old or unwritten constitutions to hold together a polity divided by rising inequality and a deliberate or negligent dismantling of the state as a provider of public goods. In much (but not all) of Central and Eastern Europe, in contrast, zealous Western reformers misunderstood as democratic revolutions what were in reality national emancipation movements. And it seems only too likely that West Germans greatly overestimated the joy their eastern brothers and sisters would feel upon a reunification based on what the writer Jana Hensel has called “das egalitäre Versprechen,” the egalitarian promise: You’ll all become like us. Ouch.

So at least some of the protest against liberal democracy is the anger of those who feel unheard, culturally marginalized, disrespected. It is a displacement emotion — like the anger directed against migrants in regions where there are few or no migrants, but very high emigration rates that engender a fear of permanent exclusion in those who are left behind — but it is no less real. Understanding this could be a first step to empathy and building bridges across the divides.

And yet I have to take issue with those who say that illiberalism is no more than a reflexive response to liberal hubris, or that Europe should stop being a democratic missionary and lead purely through the power of example, becoming a walled Kantian garden, or a “monastery.”

Liberal democracy is not a system of governance like any other, but (as Judith Shklar wrote in her seminal essay “The Liberalism of Fear”) the only system that restrains state violence against the individual. It needs to be defended against its very real enemies, who misdirect and exploit the anger of the disrespected for their own gains. As for the prescription that Europe ought to preserve the purity of its liberal democracy at home but abstain from advocating it abroad, it is entirely at odds with the reality of Europe’s fluid and vulnerable situation within the modern paradigm of great-power rivalry. Challengers and adversaries like Russia and China have established themselves as assertive players within the European continent. Europe, for its part, is existentially dependent on its openness to the global movement of ideas, data, goods, and people; but liberal democracy is its greatest comparative advantage. The Europeans may have to learn to protect this treasure without either the United States or United Kingdom at their side.

Freedom and identity. The ultimate lesson of 1989, then, is this: History was never linear or inevitable. It was then and is now the product of decisions, of choices, of freedoms, of responsibility taken. To quote Thomas Bagger on Germany again: “The history of unification represents hope even under the most adverse circumstances … We should not expect the inevitability of a better future, but should never discard its possibility — including the emancipation of those who today suffer the consequences of authoritarian rule.”

The Europe we have could use some work — but it is still the best the continent has ever seen.

In fact, predictions of the imminent demise of liberal democracy would appear to have been somewhat premature. The protests in Russian cities and in Hong Kong speak powerfully to the universality of the human desire for self-determination. In Austria, Italy, and Slovakia, or the cities of Istanbul, Warsaw, and Budapest, populists have been thrown out or kept at bay. The Europe we have could use some work — but it is still the best the continent has ever seen.

And notwithstanding the prophets of nativism who would separate and segregate us into strictly homogeneous tribes, most of us live comfortably in our multiple identities: the local, the regional, the national, the European, and the Western. Two generations ago, my clan was lily-white and firmly Protestant. Now, my extended family encompasses relatives of Swiss, Slovene, Ghanaian, American, and Taiwanese origin; it includes Jews, atheists — and even Catholics. I myself, for all my wandering, was baptized in a four-century-old church in Ober-Wegfurth, a village in the farmland of the Fulda Gap, the same chapel where my parents were married and in whose graveyard my ancestors have been buried for the last 400 years. But even more importantly, I once made a decision to cleave to my country, and all its baggage.

My generation, “the 1989ers,” whose trajectory into real life was re-shaped so profoundly 30 years ago, now finds itself at the cusp of its own historical arc, and before its own choices. We are still grappling with the lessons of the past as huge new transformations loom ahead. But history will not wait for us.

The Europe we were given in 1989 is now ours to lose, or to keep.