Sub-Saharan Africa is a continent that faces serious food security problems that threaten millions of inhabitants. The problem of African food security is further exacerbated by an over-reliance on rain-fed agriculture, conflicts that displace farmers, and insecure property rights. Increasingly, the problem of climate change is placing severe constraints on Africa to be able to feed its people. It is quite evident that the “Africa rising” story is not sustainable unless Africa can adequately feed her people. The precarious food security situation is compounded by skepticism of the adoption of biotechnology, such as genetically engineered crops. There is need for African leadership, the private sector and civil society to seriously rethink adoption of genetically engineered (GE) crops, and to support national frameworks for biosafety to review and approve GE crops for use by farmers.

In this article we refer to crops that scientists have added new traits or characteristics via biotechnology methods rather than conventional breeding. There are a few alternative names for GE crops, e.g., genetically modified (GM) or genetically modified organisms (GMOs), but genetically engineered is the term preferred by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Arguments in support of the adoption of GE crops—such as boosting yields and increasing food security—have already been well articulated by scholars such as Calestous Juma of Harvard. In addition, GE crops have the potential to play a significant role in climate change adaptation. As noted in a Business Daily article, President Obama has also endorsed biotechnology as a way to face climate-related agricultural challenges. Indeed, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s Fifth Assessment Report has announced some challenges for global agriculture: Yields are expected to decline by 2 percent per decade due to climate change, while the demand for food is expected to increase by 14 percent per decade. To adapt to environmental pressures, African countries need to build their capacity to assess the risk of GE crops and manage the use of biotechnology.

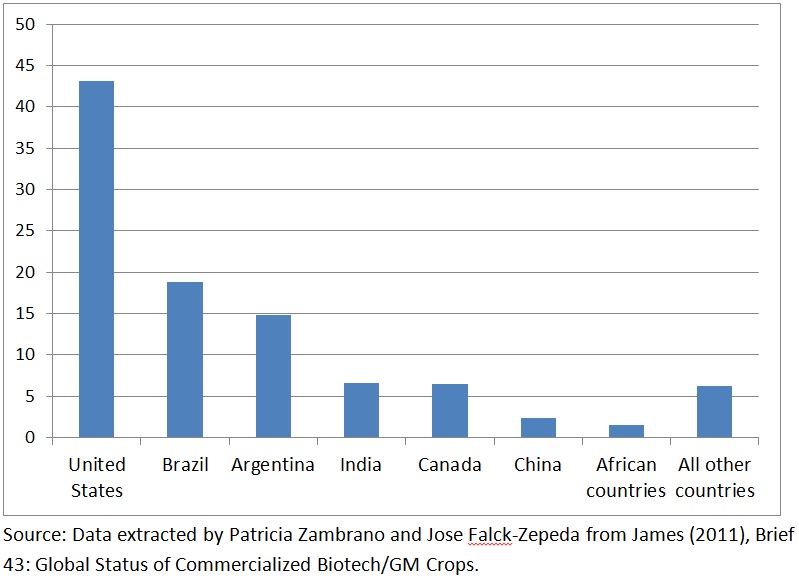

According to the World Bank, 96 percent of African cropland is rain fed, which makes African agriculture heavily dependent on climate (e.g., rainfall and temperature). As noted above, climate change is expected to exacerbate the already wide rainfall deficit in Africa. In addition, warmer climates increase the breeding of insect pests and diseases, which lower crop productivity. Thus, drought- and pest-resistant crops are highly relevant to Africa’s ability to adapt to increased variability in rainfall and temperature. Advances in genetic modification have created disease- and pest-resistant plants (e.g., Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) cotton) and crops that can tolerate harsh environmental conditions (e.g., Droughtgard maize). However, adoption of GE crops in Africa to date has been minimal (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of Genetically Engineered Crop Acreage (By Country)

Concerns about GE Crops

The adoption of genetically engineered crops in Africa is hindered by skepticism and a politicization of the issue, impacting access to the technology. While concerns about the safety of GE crops top the list, a recent meta-analysis of a decade worth of literature in the Critical Review of Biotechnology finds that the literature supports the argument that transgenic DNA is not substantially different than any other DNA already present in food.

Beyond the fear that GE crops are unsafe, critics have concerns about the impact on trade, compatibility with local farm systems, and dependence on foreign private sectors for the technology. The production of GE crops potentially has adverse impacts on trade since some countries (e.g., France and Germany) have bans or require special labeling for GE crops. However, currently, GE crops that hold the potential to help African farmers adapt to climate change are for consumption and food security (e.g., maize, rice, sweet potato and cassava) and are not typically products exported to Europe. Take Kenya for example: Tea is the number one agricultural export followed by cut flowers and coffee, but there is no GE tea crop product available on the market. In essence, current GE products targeted to Africa are mainly for the very real concerns of food security and adaptation to climate variability; the impact of GE crops on trade is likely to be minimal. One exception to this conjecture would be the case of Egypt, where cotton is the leading agricultural export, and cotton does have a GE product available.

Critics of GE crops in Africa also note that the GE crop supply chain is incompatible with small-holder farm systems. Small-holder farmers are used to saving seeds from previous harvest, while GE crops require farmers to purchase new seeds each year to maintain desirable genetic traits because of the so called terminator gene. Yet, farmers also need to repurchase conventional hybrid seeds (those bred through conventional crop breeding techniques) and the uptake of these seeds in Africa is also low. The solution here should be not to ignore GE crops, but instead to educate farmers on the best practices for both hybrid and GE crops.

Another common criticism is that farmers will become dependent on the foreign private sector for seed stocks. In many countries in Africa there is a lack of biotechnology infrastructure to supply GE seeds locally. This is a valid concern. To avoid dependence on foreign supplies of GE seeds, support for local production capacity is required, and some organizations are beginning to address this challenge. To this end, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, and the U.S. Agency for International Development are funding a project with the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF) in Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda to produce drought-resistant maize seed. In addition, Monsanto has contributed its maize germplasm and drought and insect gene traits royalty-free to assist the AATF program.

How Can African Countries Support Adoption of Biotechnology?

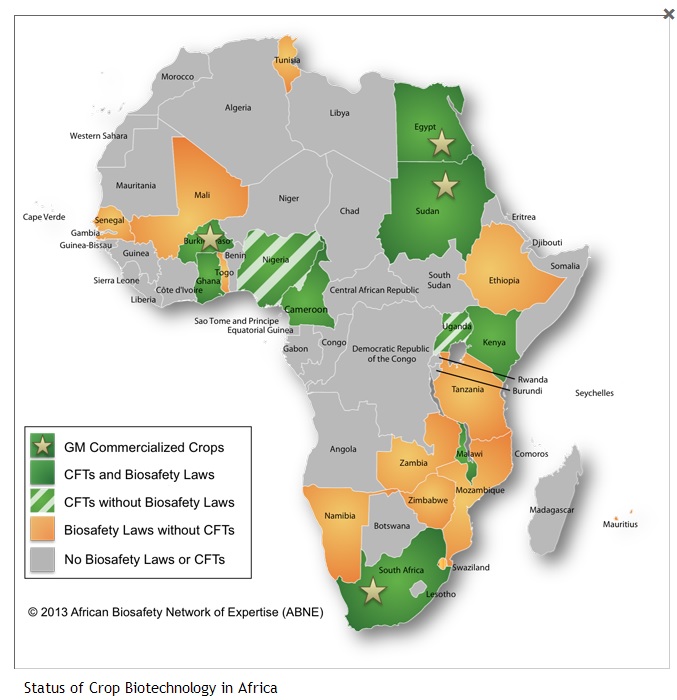

As observed, there is a general skepticism about the health, safety and socioeconomic effects of GE crops. African countries generally lack the capacity and infrastructure to adequately evaluate GE crops and thus need to build their biosafety and biotechnology regulatory frameworks as a first step toward increased GE crop adoption. According to the New Economic Partnership for African Development (NEPAD) African Biosafety Network of Expertise, only 20 countries in Africa have functional biosafety laws (Figure 2). Nigeria and Uganda have contained field trails (i.e., testing in a controlled environment) without biosafety laws. Countries need responsible regulation, but also need to refrain from creating roadblocks for farmers when setting up their national biosafety frameworks. A recent Chatham House report, “On Trial: Agricultural Biotechnology in Africa,” found that 18 genetic traits for African crops have not moved past the contained field trial phase or pre-field trial stages since 2010. Indeed, there is a great opportunity for Africans to invest more in national biosafety frameworks that build on existing institutions to increase the usage of GE crops while minimizing the associated or perceived risks. In the United States, for example, the Food and Drug Administration examines the risks of GE crops. In order to receive approval, GE crops must be as safe as non-GE crops, which means they must provide the same range of nutrients and are only just as likely to be toxic or cause allergic reactions. African countries that have existing food safety regulations should consider incorporating biosafety frameworks into their existing food safety institutions rather than starting from scratch with new agencies.

Figure 2. Status of Biosecurity Frameworks in Africa

In order for GE crops to really take off in Africa, consumers will have to be educated as well. For example, the principal agricultural economist at the East African Community (EAC) has recently called for a public education campaign to accompany the proposed harmonized EAC policy on biotechnology. Moves like this have begun to reduce public concerns over GE crops. However, researchers from Chatham House warn civil society organizations against fear mongering and derailing the benefits that could result from the use of biotechnology. The Chatham House researchers refer to European civil society organizations that campaign against the use of GE crops in Africa.

The use of most agricultural technology results in tradeoffs and costs. In the case of an increasing population and increasing climate variability, the benefits of GE crops to agricultural productivity potentially outweigh the even larger costs (e.g., starvation, death, long-term reduction in human capital potential) that arise from food insecurity. This is a credible reason for African governments to champion national biosafety frameworks that take advantage of the interrelated food security and climate adaptation benefits that biotechnology can offer. As with all agricultural products, there are risks related to the adoption of genetically engineered crops, but with an appropriate food safety regulatory framework, such risks can be greatly minimized.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Genetically Engineered Crops: Key to Climate Adaptation and Food Security in Africa?

September 4, 2014