For years our research on happiness has been finding progress paradoxes in the globalization process, and we have been tracking cohorts of “frustrated achievers” across a wide range of countries, especially in Latin America. These are individuals who are not poor but rather in or near the middle of their income distributions, above average education levels, and who have experienced significant income mobility. At the same time, they are much more frustrated with their economic situations and less satisfied with their lives than the average. Given the important role that the middle class plays in sustaining markets and democracies around the world, how should we understand these frustrations? Are they linked to the social and political unrest that many countries have witnessed in recent years?

In another Brookings blog post co-authored with Soumya Chattopadhyay and based on Gallup data, we show that these “frustrated achievers” demonstrate the highest levels of stress and the most skepticism about social mobility in several countries in the world, ranging from Brazil and Chile to Ukraine, Thailand, and Turkey. Their traits are also remarkably similar to those of the “prototypical” protestor in many of these countries.

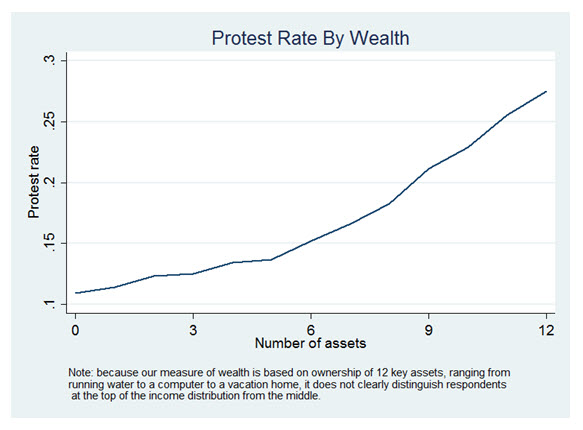

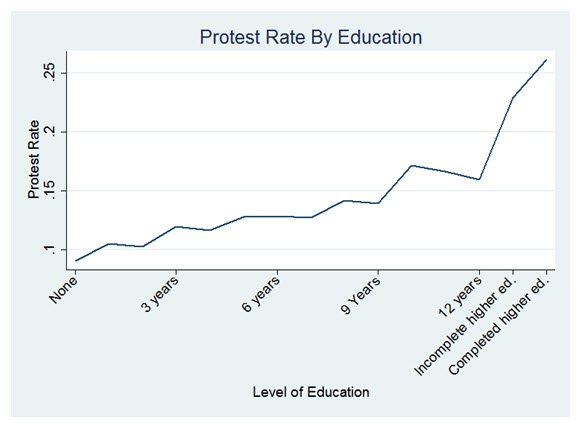

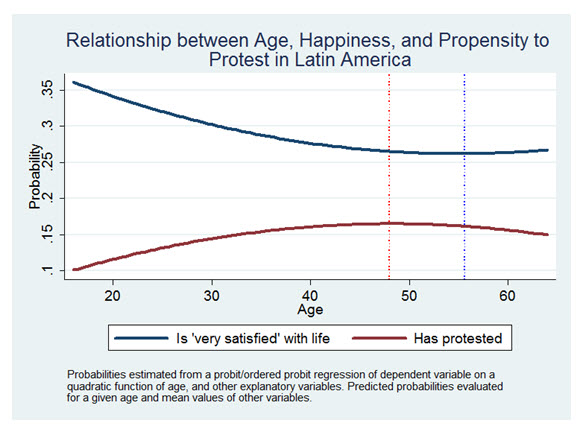

Latin America is clearly a region where people exercise their rights to civic participation: roughly one in six of our 66,000 respondents reported to have participated in an authorized protest. But what is most remarkable is the extent to which the traits of those who report to have participated in protests mirror those of our frustrated achievers. The cohort most likely to protest is roughly middle aged (or older), has above average levels of education (12 years and above), and has above average levels of income, just like our frustrated achievers. The charts below tell the story.

Of course getting accurate data on who is actually participating in protests is difficult. Survey teams are usually not on site at the unexpected moments when protests break out, and people are unlikely to report their participation in ongoing unrest. As a next best step, we looked back in time, based on Latinobarometro data for Latin America from 1995-2008, a time period in which many countries in the region made great strides in reducing poverty. We took advantage of a question in the survey which asked respondents if they had participated in an authorized demonstration, with the possible responses being “never”, “I might”, and “I have”. We tagged respondents in the data who reported to have actually protested (as opposed to including those who indicated that they might protest).

The charts below tell the story of frustrated achievers in Latin America—middle-aged people with above levels of education and above average levels of income who have nevertheless participated in an authorized protest.

The first chart shows the relationship between propensity to protest and wealth levels in the region, and suggests a monotonic increase of propensity to protest as wealth levels increase. An important caveat is that our wealth index does not capture the assets of the very wealthy and, as such can only suggest that people in the middle or top of the income distribution are much more likely to protest than are the very poor.

The second chart, below, shows that those with high school education and above are much more likely to protest than those with less than high school levels.

This last chart shows how happiness and propensity to protest have inverse relationships with age, with the highest point in the propensity to protest and age relationship being roughly the opposite of the lowest point in the happiness and age relationship.

Is this simply a demographic phenomenon in which people are more likely to protest at the point in their lives when they are the least happy? Perhaps that is part of the story; it is surely not all of it. These same respondents, while fairly confident about their own economic situation compared to the average, are less likely to believe that a poor person who works hard can become rich; are less satisfied with the education and health care they have access to; and are less likely to believe that the income distribution in their country is fair. Thus while they have made progress, they are skeptical about the system they are working in and are dissatisfied with how it benefits the non-wealthy.

This is not a story that is unique to Latin America. It fits the story told by trends in the distributions of income and opportunity in the United States—and has been written about repeatedly in Brookings Social Mobility Memos blog. It is a story about middle class frustration with an economic system which lacks the institutions to preserve investments in hard work and to provide the public services that will support the next generation’s progress, while at the same time providing disproportionate rewards to the very wealthy. While paying attention to the middle is hardly a catchy tune (nor does it minimize the needs of the poorest), it may be one that is key to economic and political stability in our increasingly integrated world economy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Frustrated Achievers, Protests, and Unhappiness in 3 Charts

June 17, 2014