On Wednesday, House Democrats are scheduled to hold their internal party vote to select the party’s nominee for speaker of the House for the 116th Congress, which will convene in January. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) remains the front-runner, but her path is far from smooth. Here are four key questions about Pelosi’s prospects for success.

1. Who opposes Pelosi’s speakership bid?

According to the Washington Post’s tracker, 22 members, or about nine percent, of the incoming Democratic caucus have announced that they plan to oppose Pelosi for speaker. Another larger group (46 members, or about 20 percent) have “dodged questions” on the matter. Generally, we can divide these “Pelosi skeptics” into three categories (though they’re not mutually exclusive). The first group are incumbent House members whose frustration appears generally related to how Pelosi has functioned as the Democratic leader, centralizing power in the hands of a small group and making it more difficult for more junior members to garner influence. A second faction is comprised of newly elected House freshmen who, in an attempt to portray themselves as independent-minded, announced on the campaign trail that they would not support Pelosi for speaker. The third group, comprised of members of the Problem Solvers Caucus, are attempting to use the speakership race to extract rules changes that they argue would increase the influence of rank-and-file members in the legislative process.

2. Why does their opposition matter?

Under long-standing House practices, an individual must receive the votes of “a numerical majority of the votes cast by members ‘for a person by name’” to be elected speaker. If all members of the House are present and voting, then, 218 votes are needed to win. As a result, if more than 17 Democrats refuse to vote for Pelosi and instead cast their votes for a different candidate, she would not have sufficient support to be elected. (If not all representatives are in attendance, or if some number choose to vote “present” instead of affirmatively for an alternative candidate, the number needed to win falls. Matt Glassman lays out how that strategy could work nicely here.)

The speakership is unique in this way; other party leaders are selected by a majority of each party’s caucus. As a result, the selection of a key national partisan figure requires the support of a supermajority of that party’s House membership. Since the second half of the 19th century, this has not been a major obstacle, as members have generally supported their party’s nominee for speaker on the floor. But that norm has weakened slightly in recent years. Given Pelosi’s especially visible status as a national figure, her bid for the speakership is perhaps especially vulnerable to becoming a broader political fight.

3. How is Pelosi countering the opposition?

So far, Pelosi has used, in the words of speakership expert Matt Green, “carrots, not sticks,” to persuade individual members to back her candidacy. Two members who had initially opposed Pelosi—Brian Higgins of New York and Marcia Fudge of Ohio—have agreed to support her after being offered specific positions of influence in the new Congress. Similarly, the House Progressive Caucus got Pelosi to agree to install more progressive members on a number of important House committees as she worked to solidify blocks of support for her speakership bid.

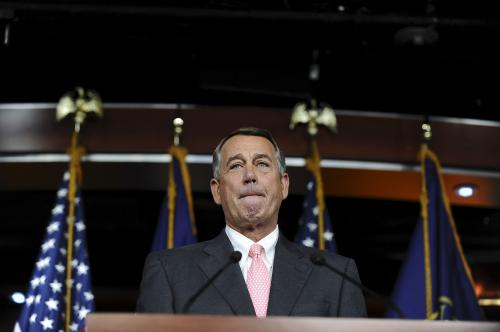

Of the three major groups of skeptics, the Problem Solvers have articulated specific demands that, if accommodated, could get them to support Pelosi: “debate and timely vote” on bills co-sponsored by at least 290 House members; a guarantee that any amendment supported by at least 20 members of each party can be considered on the floor; and a requirement that each committee consider at least one bill in its jurisdiction sponsored by each of its members as long as the measure has at least one co-sponsor from the opposite party. A group of freshmen are pushing for representation for their class on influential committees and for other process commitments, but their asks are not explicitly tied to the speakership race. The relatively small role played by specific demands in the bargaining process represents a difference in strategy from that of the House Freedom Caucus, which clearly articulated its demands of a new speaker during the 2015 debate over who would succeed John Boehner.

4. How does this conflict fit in with broader dynamics within the House Democratic caucus?

As political scientists Matt Grossmann and Dave Hopkins have argued, the contemporary Democratic Party is largely “a coalition of social groups seeking concrete government action”—a dynamic that helps explain why Democratic legislators tend to be more active in groups focused on particular constituency interests, like the Congressional Black Caucus. Navigating the demands of these competing groups makes it difficult for a leader like Pelosi to please everyone all of the time. Take, for example, the debate over whether House Democrats should follow their Republican colleagues in instituting term limits for committee leaders. The Pelosi skeptics who object to the lack of upward mobility within the party’s power structure might welcome this change, but groups like the Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus “have long favored seniority as the surest way for their members to rise in the ranks.” If Pelosi is able to navigate her way to victory in the speakership race, it will be another reminder of her effectiveness at managing the competing interests that make up her party.

Commentary

Four key questions about Nancy Pelosi’s bid to be the next speaker of the House

November 27, 2018