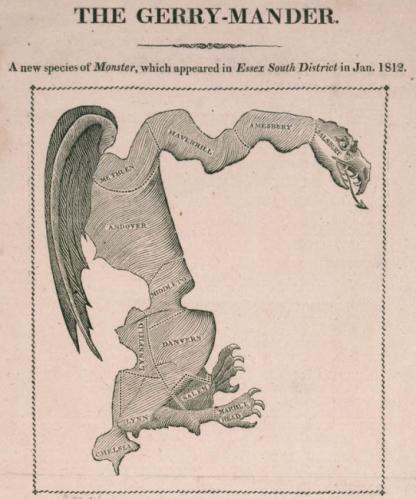

In a 5-4 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts. This came as no surprise to close observers of the half-century of litigation that proceeded it. While the Court had long acknowledged the possibility (even sometimes the likelihood) of constitutional violations from partisan gerrymandering, it was openly skeptical of identifying a workable standard (one grounded in a “limited and precise rationale” and “clear, manageable, and politically neutral”) for courts to use in resolving such claims. Chief Justice John Roberts showed his hand in 2017 during oral arguments on a related case (Gill v. Whitford) by dismissing new scholarship on developing such a standard as “sociological gobbledygook.”

Nonetheless, it was jarring to read the stark and definitive closing to his decision on behalf of the Court: “The judgments of the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina and the United States District Court for the District of Maryland are vacated, and the cases are remanded with instructions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. It is so ordered.” C’est fini. The federal judiciary will not be in the business of adjudicating partisan gerrymandering claims.

The two consolidated cases were strong. Both gerrymanders were egregious. One, affecting the entire state delegation in Congress, was crafted by Republicans in North Carolina; the other, centered on a single congressional district, by Democrats in Maryland. Plaintiffs applied a three-part test, examining intent, effects, and causation, and marshaled considerable evidence that the discriminatory effects in these two plans could not be due to legitimate redistricting objectives. They utilized the work of scholars who had risen to the challenge issued years earlier by Justice Anthony Kennedy to develop workable and neutral standards. In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan provides a clear, understandable explanation of how big data and computer simulations can convincingly identify redistricting outliers. Plaintiffs acknowledged that redistricting is inherently political and limited their remedial attention to only the most extreme cases. It’s hard to imagine a more powerful case or a more compelling constitutional argument for the Court to enter this political thicket than that contained in Justice Kagan’s dissent.

Those seeking a redress of their grievances with partisan gerrymandering will have to turn to other venues and tactics. In his majority decision, the Chief Justice wishes them godspeed—with legislative remedies by Congress and state legislatures, popular initiatives to establish redistricting commissions and criteria, state constitutional amendments and litigation in state courts—just not in the federal courts. Most of these efforts have been underway for years—with some recent successes in states such as Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan but plenty of obstacles as well. Only half of the states allow popular initiatives and sitting elected officeholders are hardly a hotbed of redistricting reform.

Two final thoughts. First, partisan gerrymandering is more a consequence than a cause of polarization. It is an affront to our democracy (one of many) and now also a weapon in the war underway between the parties for control of national and state government. Republicans have been living off their success in controlling the 2010 cycle of redistricting and they have every incentive to try to repeat that success in the 2020 round. Their opposition to reform in this arena is almost certain to continue. The Roberts Court, with a conservative majority appointed by Republican presidents, has ruled in favor of the Republican position on voting rights (Shelby), campaign finance (Citizens United) and now partisan gerrymandering. There is a serious mismatch between the Republican Party’s minority position in the electorate and their majority influence on policymaking.

Second, our single-member, first-past-the-post electoral system naturally underrepresents residents clustered in large metropolitan areas. This obstacle to fair representation facing Democrats is much more serious than partisan gerrymandering. Either massive consecutive electoral victories or serious electoral reform (such as multimember districts) will be required by Democrats to overcome this anti-majoritarianism.

Commentary

For partisan gerrymandering reform, the federal courts are closed

June 29, 2019