From 2009 to 2014, Claudia Costin served as secretary of education for Rio de Janeiro and led the city through a series of reforms that resulted in dramatic improvements in children’s enrollment, retention and learning in schools, particularly among some of the most disadvantaged communities.

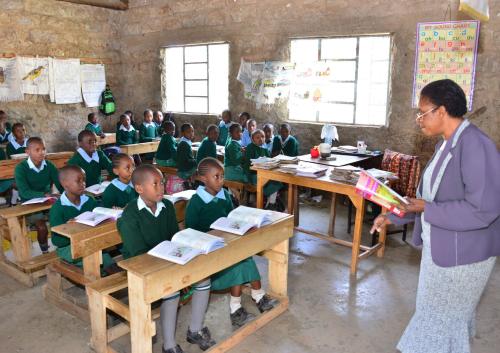

One of the most celebrated and bold innovations was the “Schools of Tomorrow” program, which focuses on reducing school dropout and improving learning in 155 schools in the poorest, most vulnerable, drug-affected and violence-ridden areas in Rio’s “favelas,” or slums. Some of these schools went from being among the lowest performing schools in the country to becoming the top performers. Between 2009 and 2012, Rio saw a 22 percent increase in its score in the Basic Education Development Index for middle school and 33 percent specifically for the Schools of Tomorrow. The Schools of Tomorrow program has six pillars, including: extending the school day, providing remedial classes, training teachers to teach in a dynamic way, implementing a hands-on science program, providing comprehensive health services, and involving the community.

Costin has recently left government and joined the World Bank in Washington, D.C. as the new senior director for education. To support our research into how we scale up quality learning programs, Costin sat with me to reflect on some of the lessons from her experience.

Jenny Perlman Robinson: From your experience as secretary of education, what were the key drivers behind Rio’s success in improving children’s learning?

Claudia Costin: In Brazil, our teacher training colleges historically have focused on the more theoretical aspects of education—the history, sociology and philosophy of education. There is less emphasis on the content and practical aspects of teaching. Therefore, we had to emphasize how to teach in the teacher selection process. Prospective teachers have to give a class and are assessed for that prior to being admitted. It’s an integral part of the selection process.

Another factor was to have a clear curriculum in order to precisely define learning expectations and standards so that teachers could know what was expected at each grade level. Given that there is so much material to master, we built a digital platform—Educopedia, prepared by the teachers for the teachers—that connects digital materials to the curriculum.

Third, we invested in early childhood education as a way to not only build school readiness but also fight inequality, including a School for Parents of young children. Lastly, ongoing assessment and feedback is critical. In Brazil, I have seen a lot of standardized tests that take too long to give feedback to teachers. Without that information, teachers cannot re-assess the way they teach, at least with the same group of students. So we built our own system to assess each year, with clear feedback to the teachers.

JPR: Given the ambitious set of reforms enacted under your administration, do you have any thoughts on how to ensure that successful reforms last beyond a particular administration or someone’s time in office?

CC: Most people would say that you have to transform these reforms into a law. In Latin America, there are lots of laws that are written but that do not happen, things that cannot be enforced. So we decided that in addition to building laws, we needed to build ownership from the teachers’ perspectives. This means using professional development and jointly creating what is needed to ensure that, should the secretary change—which happened recently in Rio de Janeiro—the same policies would continue. The current secretary has already been in office for five months and things are still continuing. We have the curriculum in place, we have the assessments, we still have the digital platform ongoing with teachers preparing what is needed, the early childhood program is continuing. Through my experience as a public policy specialist, I see the best way to ensure continuity of any program is to really bring results, as then it becomes something desirable.

JPR: When discussing Schools of Tomorrow, you’ve shared that rather than developing the perfect prototype in a pilot setting and then gradually rolling it out, you scaled the initiative up quickly, allowing the program to be refined over time. What are some of the lessons from that approach? Would you do it the same way again?

CC: I think the basic approach taken in the Schools of Tomorrow program—the idea of learning by doing—was very important, because a very clear pattern emerged for the schools involved. Each violent area has its own micro-culture, its own challenges. In some of them, there were conflicts every day and violence was happening inside the school. In others, it was exactly the opposite. The drug dealers treated the community and schools as part of their fiefdom and would protect them from violence and harm. Therefore, it was not possible to have one model, or a “one-size fits all” approach to the Schools of Tomorrow.

If I were to start all over again with the Schools of Tomorrow, I would have tried to convince the mayor to double the salaries for teachers who work with the specific schools. We were successful in increasing their salaries slightly to make the job attractive for some teachers to go there, but it was not enough. One thing we introduced in the Schools of Tomorrow program was incentives. If learning increased, as measured by an external assessment, the teachers from the whole school would receive a bonus that was higher than the bonuses given to schools that were not Schools of Tomorrow. Besides incentives for teachers, as part of the program, schools received more resources and more programmatic support, such as for remedial education, science, mathematics, etc.

JPR: Where do you think we should be focusing in the future to ensure many more children and young people are learning?

CC: There was a paper from McKinsey, “How the World’s Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better,” that showcased different education systems around the world that were improving. It argued that depending on the stage where a particular system is in its performance, it should have different “homework” to address its respective challenges. And I truly agree. We cannot copy England, or copy Korea, and expect similar results. In our case, we need to go back to the basics, while we leave the field open to innovation.

One thing on the frontier to think about is, while we should have a curriculum distinct to every country, at the same time we need to have strategies for personalized learning. I think this is the way education will be in the future.

We tested this model of having personalized learning using formative assessments and the Educopedia platform. We realized that you can only have personalized learning if you have a good curriculum. Once you know what the expectations are at each grade level, you can allow kids to progress either faster or slower depending on where they are at in their learning process. Personalized learning will address the different learning styles of children in a much better way. I think this will be more and more important in the future.

Commentary

Ensuring Lasting Education Reforms by Delivering Results: A Discussion with Claudia Costin, Senior Director for Education at the World Bank

January 7, 2015