In the Trump era, immigration has become a regular topic of conversation in discourse and debates, touching a range of public policy areas—including education. The nation’s immigrant population has doubled since 1990 and has consequently transformed the demographic composition of U.S. schools.

The lion’s share of the newest American immigrants do not speak English as a native language. The growing segment of children living in non-English-speaking households creates an increasing demand for teachers prepared to serve English learners. Unfortunately, state and federal policies and teacher preparation programs have not sufficiently prioritized training teachers for this growing segment of the student population, and teachers are, therefore, left unprepared in the classroom.

Let’s take a look at this population of English learners, and what states, teacher training programs, and the Department of Education are doing to promote better quality instruction for them.

Who are English learners?

English learners (ELs) is the most rapidly growing subgroup of public school students across the United States—the number of ELs grew by roughly 60 percent over the past decade. ELs currently account for nearly 10 percent of all students nationwide.

An important element of the EL label as used in schools is that it only applies to students still learning the language, and generally does not include those who have already successfully learned English from another foreign language. Including both former and current ELs more than doubles the proportion of public school students from non-English-speaking backgrounds. While many ELs are themselves immigrants, the majority of ELs are second-generation immigrants who are born in the United States and do not speak English as a first language at home.

In addition, EL students lag far behind their native English peers in school outcomes. The achievement gap between current EL and non-EL students in fourth-grade reading and in eighth-grade math is about 40 percentage points. In addition, EL students take fewer advanced courses than non-ELs, and only 59 percent of EL students graduate from high school in four years.

English learners in every classroom

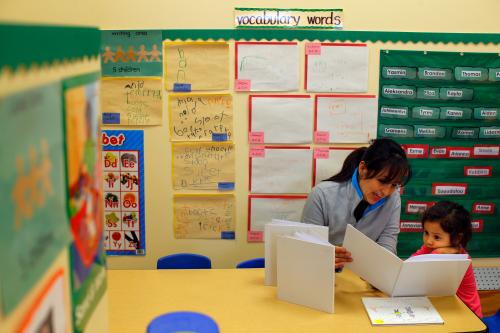

Historically, ELs were largely separated from native English students with their own sheltered classrooms that prioritized English instruction, often at the expense of going light on other academic content. In recent decades, though, providing students instruction in mainstream classrooms has become more common. Moreover, researchers promote more integrated academic instruction as the preferred strategy to develop students’ English skills. This integrated instructional approach more closely resembles mainstream instruction and may plausibly result in more EL students making a transition between sheltered and mainstream classrooms sooner.

In addition, the geographical spread of immigrants implies an increasingly diffuse population of ELs across schools. In recent decades, immigrants have begun to move beyond historical immigration gateways in major cities. They are now moving to traditionally white areas, including suburbs and rural areas, and as a result, more than half of all ELs in public schools are now outside of city centers.

These trends in both immigration settlement and the way English is taught to non-native speakers combine to imply most teachers, regardless of where they teach, will have a very good chance of encountering ELs during their careers. This creates the need that not only specialists but also general teachers are prepared to support ELs in the classroom.

Though the convergence of these trends make the need for teacher training more urgent, this is not something that should surprise us. At the turn of the 21st century, a national survey reported 41 percent of public school teachers in a variety of locales taught students with limited English proficiency. Fewer than a third of those teachers had even a modest level of training to support ELs. More recent surveys put the share of teachers with at least one EL over 55 percent, but we do not see any evidence that teacher training is improving.

A checkerboard of policies and programs

Research supports the notion that teachers trained and prepared to work with EL students can effectively support their students’ development. In New York City, English as a Second Language (ESL) certification for math teachers and pre-service teacher training focused on EL-specific instructional strategies predict greater math learning gains for ELs. Another study focuses on teacher quality in the Miami area, and finds having a good teacher in general is better for EL students than just finding an average EL specialized teacher; however, holding bilingual certification is differentially predictive of improving EL student achievement among all teachers. In other words, good teachers with EL training appears to be the optimal combination.

In spite of the growing need for both specialists and generalists trained in EL instruction, training EL-ready teachers has not been a priority for many teacher preparation programs. A 2014 report from the National Council on Teacher Quality shows that only 24 percent of programs train general elementary teacher candidates in strategies to support ELs or students not making progress in early reading. A 2016 study of practices in teacher preparation programs in six states with large Spanish-speaking populations also revealed a high degree of variation in EL teacher training across institutions. Thus, the level of preparation among new teachers to support ELs is uneven, at best.

Moreover, state policies on teacher training for both general education teachers and those specializing in ELs are a mixed bag. Many states do not require EL teachers or general classroom teachers to have an ESL, bilingual, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) instructor, or one with a structured English immersion certification or endorsement. Experts in EL instruction strongly endorse teachers working closely with ELs to hold a bilingual or ESL certification. However, only 20 states explicitly require EL teachers to have an English Learners certification; and surprisingly, states such as Florida and Colorado that have more than 10 percent of students classified as EL do not explicitly require any type of EL certification for EL teachers. Furthermore, over 30 states do not require any type of EL training for general classroom teachers beyond that required by federal law.

Recent federal policies are raising the prominence of ELs. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires all schools to begin reporting EL students’ progress on both their English proficiency and core tested subjects, and substantially increases the funding targeted toward this group. Yet, no new federal policies have prioritized teacher training for ELs, either pre-service or in-service.

It is possible that ESSA’s new accountability requirements and flow of funds could encourage states to be more mindful of teacher quality for EL students. But despite the critical importance of training teachers to meet the needs of all students, including ELs, raising the bar for teacher training and professional development remains elusive across multiple levels of teacher training and school governance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).