COVID-19 has exacerbated challenges to Africa’s food and agriculture sector and to its millions of smallholder farmers. At the same time, the pandemic has accelerated innovative efforts to develop and deploy the transformative power of digital technology to address these problems in ways that leapfrog past practices and traditional solutions. Emerging evidence from Asia and Africa suggests that digital technology holds promise to dramatically enhance smallholder productivity and incomes by increasing on-farm and off-farm efficiency, enhancing traceability, reducing vulnerability to counterfeit products, and improving farmers’ access to output, input, and financial markets. The change is driven by the introduction of new forms of intermediation and the collection, use, and analysis of massive amounts of agriculture data to disrupt existing business models. New strategic partnerships between the public and private sectors are an essential component for reaping the positive impacts of digital technology and avoiding unintended and unwelcome secondary effects.

Digital technology as a transformational force to drive scale

Digital technology is transforming the agricultural sector through the application of innovative tools and new business models. For the first time, many people in the value chain, including smallholder farmers, have access to real-time data and computational power making possible more effective selection and timing of product-to-market decisions, provision of credit, and access to micro-insurance.

Digitized agriculture data is also creating network effects to drive scale. Coupled with the increasing embrace of the sharing economy, digitization and artificial intelligence make possible new business models and e-commerce platforms that connect farmers directly with markets, service providers, and aggregators, thereby shortening the value chain and increasing the profitability of smallholder farming. The sharing economy has also made it possible for smallholder farmers to efficiently access mechanized tools to improve their crop yields.

Importantly, the benefits go beyond increased yields: Given that digital technology holds particular appeal for younger workers, integrating it into agriculture through entry points like precision farming, equipment leasing, service provision, and e-commerce can address the major challenge of attracting job-seeking and entrepreneurial youth. Given that 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s population is under 30 years of age, nowhere is the job creation challenge more acute.

Already, Asia has moved ahead quickly on the use of digital innovations in smallholder agriculture. Africa is demonstrating it has the potential to do the same. Digital technologies can provide the following potential benefits in agriculture:

- Empower smallholder farmers to leapfrog and harness new business models such as the sharing economy (e.g., HelloTractor, a Nigerian agricultural technology (AgTech) company that offers a farm equipment sharing application similar to Uber) or the fast-paced growth of e-commerce such as Pinduoduo in China (one of the largest e-commerce platforms for agriculture) that has grown to 800 million customers in six years.

- Derive value from agriculture data and create the network effect to drive scale. A good example is Twiga in Kenya, a business-to-business, mobile-based, e-commerce marketplace platform that delivers food produce to the mass market by digitizing the supply chain, cutting out layers of middlemen, eliminating food waste, and reducing food prices.

- Gain efficiency and reduce transaction costs through the digitalization of different processes to create transparency. Tanihub Group, one of the largest AgTech companies in Indonesia that connects farmers to consumers by removing the middlemen as well as providing financing to smallholder farmers is one example.

- Democratize access to market intelligence to create an integrated mobile platform of digital services for farmers. DigiFarm, powered by Safaricom in Kenya and which has expanded to Tanzania, Nigeria, Pakistan, India, and Myanmar, offers farmers one-stop access to lower-priced farm inputs, loans, learning content on farming, as well as access to markets.

- Create jobs for the new generation of tech-savvy farmers driving on-farm and off-farm opportunities such as Million Farmers in Kenya and Millennial Farmers in Indonesia. These programs are designed by the ministries of agriculture in their respective countries to encourage the technology-savvy youth to become farmers.

Implications for public policy

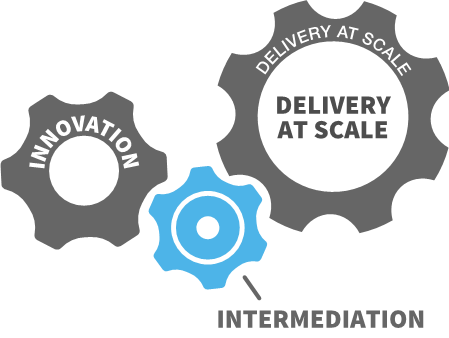

One way to understand the process of productivity enhancement is as three interlocking gears: innovation, delivery platforms for goods and services, and the intermediation that results in moving specific innovations into wider use (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prioritizing “intermediation”—the broken part of the innovation value chain

Source: Authors’ illustration.

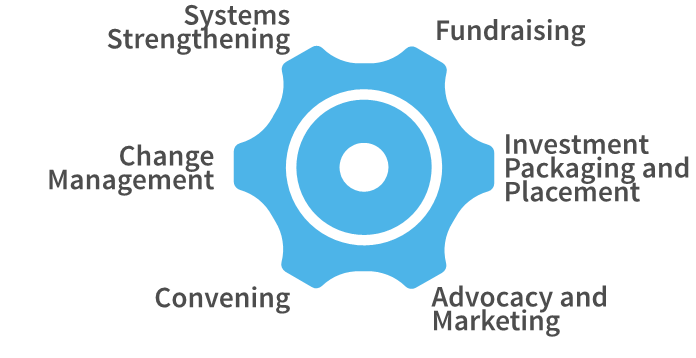

Evidence suggests that the most vexing problems limiting smallholder agriculture in Africa—and thus the biggest opportunities for dramatic breakthroughs—concern this middle gear, intermediation, which actually includes a number of different, vital functions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Functions of intermediation in the innovation value chain

Source: Authors’ illustration.

Here, especially, digital technology can play an important role, but obstacles persist. Indeed, unlike other technology-based markets where these intermediation functions are performed by venture capitalists and equity investors, the financial incentives to intermediation in smallholder agriculture have so far proven elusive in Africa.

At the same time, while public policy has an essential role to play in changing the incentives for transformational intermediation, one of the risks of enhancing the incentives for intermediation through subsidies and licensing agreements is the creation of, or acquiescence to, monopolies and monopsonies with the potential to concentrate power in ways that are politically unacceptable or potentially detrimental to the interests of the smallholders. There are, however, emerging examples of ways to address these issues through a combination of regulatory actions and stimulating enhanced competition from a new generation of innovators.

In addition, while digital technology can provide significant benefits in agriculture, it can potentially deepen the digital divide by excluding those who do not have access to connectivity or mobile phones. Therefore, it is essential to design multistakeholder partnerships between government, academia, and the private sector to support smallholder farmers across the entire agriculture value chain.

The pandemic has raised the urgency of food security for Africa. Simultaneously, there has been the overnight shift toward online digital services such as e-commerce, digital payment, and contactless experience during the COVID-19 lockdown. With the readiness of technology, we could accelerate the adoption of technology to increase the productivity, efficiency, and resilience of agricultural value chains and food systems across the African continent.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Digital technology and African smallholder agriculture: Implications for public policy

August 16, 2021