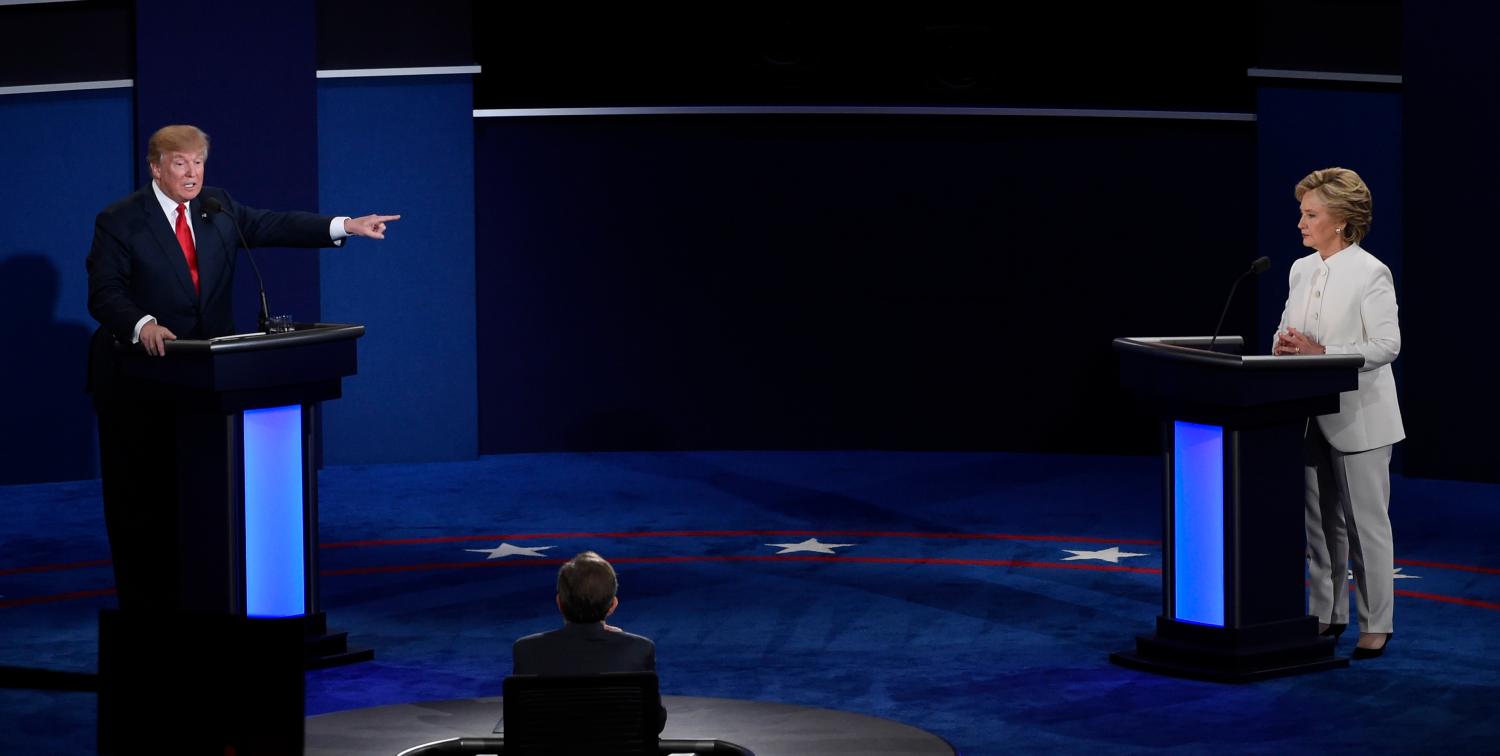

In advance of the Oct. 19 presidential debate at UNLV, The Sunday and the Brookings Institution in partnership with UNLV and Brookings Mountain West are presenting a series of guest columns on state and national election issues. The columns will appear weekly. This column originally appeared in the Las Vegas Sun.

Now that the conventions are over, let the prognosticating begin. While the eyes of pundits and the public may be glued to daily polls, it is important to consider the sharp demographic fault lines behind these numbers.

The most powerful one is a result of the nation’s recent diversity explosion: the rapid growth of Hispanic, Asian and other minority populations. Ethnic minorities accounted for 95 percent of the nation’s growth between 2000 and 2015, now approaching two-fifths of the U.S. population.

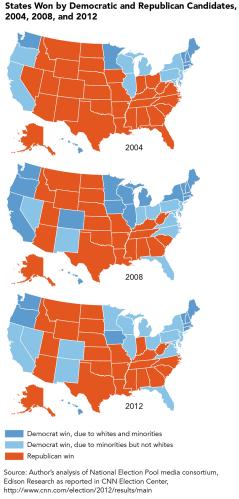

This is significant because of the racial divide in voting. A majority of whites have voted for Republican presidential candidates in every election since 1968, and blacks have voted heavily Democratic even longer, with Hispanics and Asians trending Democratic over the past several elections. Minority clout was especially dominant in 2012. Mitt Romney garnered the highest white voting margin of any Republican since Ronald Reagan in 1984. Yet he lost to Barack Obama due to the rising size and support of the minority electorate.

Key to Obama’s success was diversity’s impact on the Electoral College. His wins in Mountain West and other Sun Belt states — that in the past voted Republican — can be attributed in part to the widespread dispersion of Hispanics and Asians to western parts of the country, and the return of blacks to the South.

Nevada, where the minority share of voters climbed from 20 percent in 2004 to 33 percent in 2012, is perhaps the best example of this change. In 2012, Obama’s wins in Nevada, Colorado and New Mexico were carried by minority votes; whites in those states largely voted Republican. This also was the case in Virginia and Florida. Add in Wisconsin, where the minority Democratic vote also bested the white Republican vote, and that was enough to make the difference, among swing states, for Obama’s Electoral College win.

Even with this diversity surge, 2016 may not go so smoothly for Democrat Hillary Clinton. This is because of another demographic fault line playing out much more strongly than many anticipated — the cultural generation gap. This gap reflects the different experiences and values of older, mostly white Americans and the more racially diverse younger generations. The demographic measure of this gap shows that whites comprise 75 percent of Americans age 55 and older while racial minorities comprise 46 percent of those younger than 35.

The generational divide involves different views of diversity itself. Surveys have shown that older whites are less accepting of immigration and America’s shifting demography than younger generations who predominantly embrace these changes. This is not to frame the former as racist or anti-youth, but as disconnected from the concerns of younger people who come from different backgrounds than them and who they view differently than their own children and grandchildren.

The gap spills over into views of government: The older generation favors less spending and lower taxes compared with the young, who see benefits accruing to them from government programs associated with education, health care and a broader social safety net. Nor do they see eye to eye on social issues like abortion and same-sex marriage, which are more favored by the young. Because the two parties differ, often sharply, on these matters, the political divide between these age groups widened between the 2004 and 2012 presidential elections, with older voters favoring Republicans and younger voters favoring Democrats.

Republican Donald Trump has seized on this divide as a strategy to hold back the Democrats’ advantage from the diversity surge. Trump’s call to embrace America’s past, by making it more insular and restricting immigration, has resonated strongly with older whites.

The question then is: Given these fault lines of race, age and ideals, can Trump win in November? From an Electoral College perspective, his best opportunity lies with some of the “whiter” northern states, which Obama won by smaller margins: Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota. Winning there would require a higher voter turnout from whites, especially working-class whites, and a sharp increase in Republican support among those voters. If Trump were to take all of these states, as well as those taken by Romney, he would win 286-252. My estimates show that, while possible, this might be a long shot. To win most of these states, white voter turnout would have to be 4 percent higher than in the 2012 election, and the white Republican-minus-Democratic voting margin would have to be 8 percent higher.

There is a possibility of Trump winning racially diverse Sun Belt states like Florida, Virginia, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico or North Carolina, which Obama barely lost in 2012. Yet here he runs the risk of minority voters rallying against him, which could easily counter any increased white support he may garner. In fact, I have calculated that with a big increase in Hispanic support Clinton could take Arizona, a state won by Republicans in 15 of the past 16 presidential contests.

So the demographic lines have been drawn. The diversity that is sweeping the nation suggests that the future belongs to candidates who support issues embraced by the multicultural generation. Will this be the last presidential election that pits the old and the white against the young and the brown? Probably not. But it may be the most contentious.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Demographic fault lines and the 2016 election

August 18, 2016