Executive summary

America’s transportation infrastructure is one of the nation’s most valuable public assets—and states are situated at the hub of managing that network. Officials within state departments of transportation (DOTs) are responsible for creating multi-decade investment plans and then using those plans to steer hundreds of billions of dollars in annual spending. Said differently: States have enormous authority to determine what projects get built, where, and by whom.

Yet states also have a responsibility to invest with purpose and transparency. Considering the needs coming from within communities—including local roadway safety, high travel costs, and environmental risks—states should be helping local officials build projects to their specifications. In cases where states plan and build their own projects, the public should be able to understand how investment decisions were made and be given opportunities to provide feedback.

The challenge is judging such accountability of each state’s major actions. Even with recent federal legislation channeling more public dollars to states, federal and state laws often allow state transportation officials to obscure how they make planning and investment decisions. To better measure state accountability, we created a national inventory of transportation planning, investment, and accountability practices. We find:

- States’ long-range plans include clear goals, but there’s little accountability for reaching those goals. For example, only nine states associate performance measures with each of their goals and set targets for each measure, including Oregon and Rhode Island. By contrast, most states fail to even publish data collected on many performance measures.

- Most states do not publicly explain why they build specific projects, including whether those projects address their long-range plans. Thirty-three states fail to use any public-facing project selection systems, making it nearly impossible for stakeholders to understand why specific projects were chosen to receive funding. There are promising exceptions in Virginia and Kentucky.

- On average, states share relatively small amounts of funding with local partners, suballocating only 14% of total transportation funding to localities. Instead, the share of gas taxes states collect on locally owned roads tends to far exceed the share of revenues sent back to those local owners. However, Michigan and Arizona demonstrate that states can share more funding with their local partners.

- States make it difficult for the public to directly inform planning goals or evaluate which projects will be constructed. Less than half of states include portals for the public to submit comments or publish materials to understand how decisionmaking works. Some states do not even publish a website to describe what locally oriented funding programs exist.

- Most states use independent commissions to support their DOT operations, but their governance structures and legal authority vary widely. Commissions can improve accountability via independent oversight, but many are relatively toothless.

Generally, states are failing to operate their DOTs in a manner that promotes transparency or helps communities make local investments. Yet even with such gaps, there are many promising policies and practices that could be replicated in peer states. The burden, then, is on Congress, state legislatures, and executive officials to enact policies that will boost accountability. Some recommended reforms include: requiring published justifications for all project selections; enhancing revenue sharing and coordinated planning with localities; and expanding public communication systems to receive more input from external stakeholders.

Introduction

America’s transportation network is one of the country’s most valuable economic assets. The national network is massive, including 4.2 million miles of roads, over 140,000 miles of railways, and tens of thousands of ports and airports. Every day, that network sees over 1 billion personal trips and moves over 55 million tons of freight. Most of that infrastructure used to move all those people and goods is, critically, government-owned.

Maintaining such a vast network not only requires sizable public investment—often well exceeding $300 billion annually—but those investments must also be responsive to ever-shifting economic, social, and environmental needs. After decades of overall decline, roadway injuries and fatalities are back on the rise. Transportation continues to be the second-highest category of household spending after housing, with inflation especially high over the past two years. Transportation now emits the most greenhouse gases of any economic sector, while extreme weather continues to threaten the nation’s $6 trillion in government-owned transportation structures.

The reasonable expectation among the public, then, is that governments at all levels will be accountable for the projects and operations they invest in. It’s reasonable for external stakeholders—including local government staff, business executives, community leaders, and other interested parties—to be able to track where investment dollars flow and why. Accountability also means public officials are willing to support construction of the projects constituents want in their communities, from sparsely populated counties to the largest central cities.

Such accountability demands are significant at every level of government, but especially so for the 50 states and Washington, D.C. (henceforth referenced together as “states”).1

Governing transportation is a complex operation within every state. Departments of transportation (DOTs) are responsible for conducting long-range planning, selecting projects for capital investment, and generally maintaining safe, resilient, and efficient infrastructure. Governors hire the leadership for each DOT, giving them an opportunity to define the agency’s high-level priorities, budget, and other policies. Legislatures control annual public spending and set foundational planning and investment laws that their DOT must follow. In many cases, legislatures authorize independent commissions to provide additional oversight and advice related to revenue, spending, and project selection policies.

While roles and responsibilities vary across the country, state officials have significant authority to determine how the transportation system works within their borders. Some authorities are capital-intensive, determining where to construct roadway projects and using eminent domain. Others are more operational, such as setting speed limits on local-serving roads, crafting pedestrian policies at their major intersections, or even mandating local ride-hailing policies. States can control what tax measures local governments can enact to raise their own revenues, too.

Their authority is especially clear when it comes to managing the significant transportation assets they own. Roadways are their predominant asset class, totaling nearly 69% (711,435 miles) of the country’s federal-aid highways, which includes the interstates and U.S. highways. Their roads are also heavily used: While states only own about 22% of all national lane miles, state-owned roads carry 68% of all vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Some states and their independent commissions also own transit agencies (such as in Maryland and New Jersey), port authorities (Georgia and South Carolina), and airports (Hawaii and Massachusetts). Owning such large and complex assets has helped state DOT staff become experts in building and maintaining physical infrastructure.2

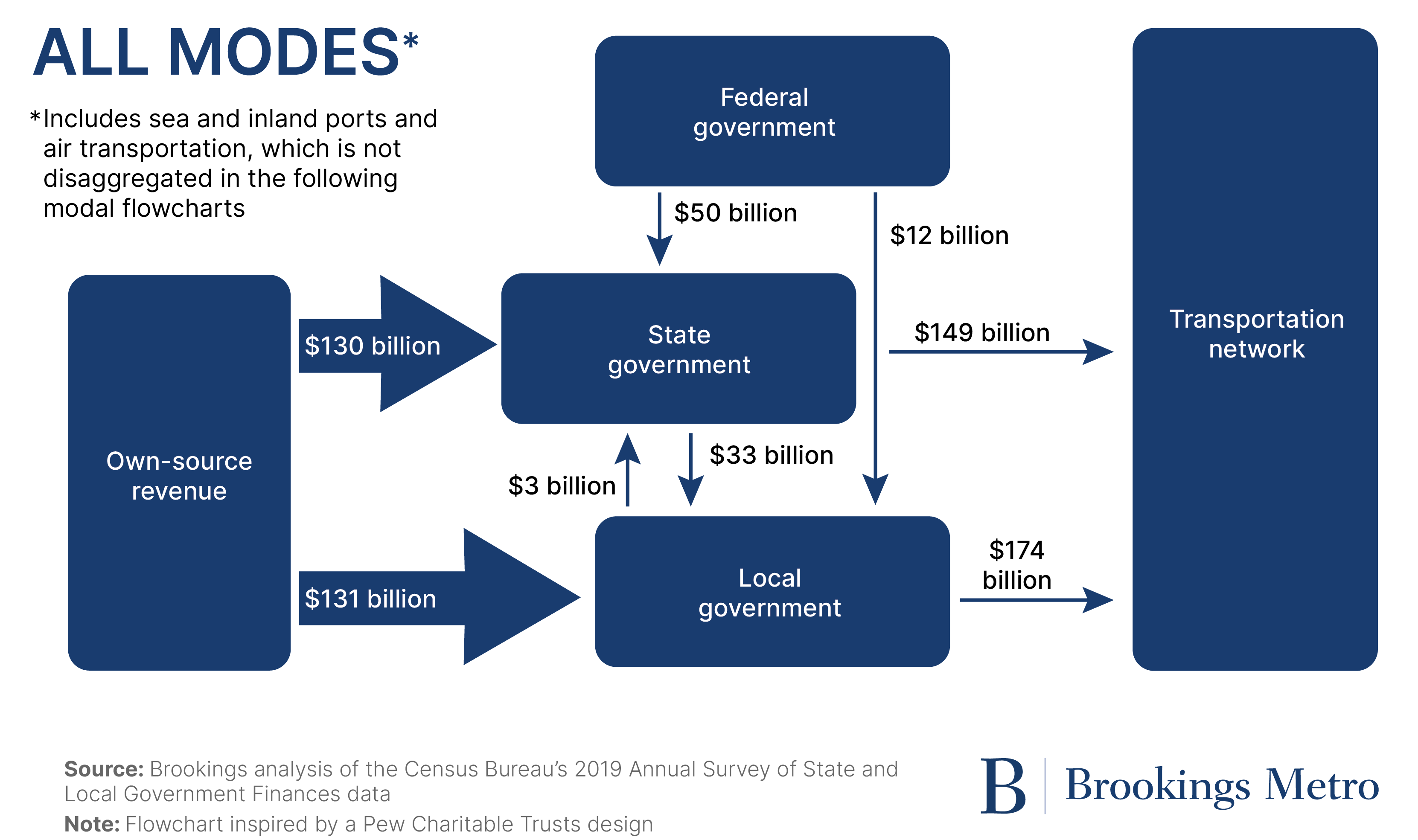

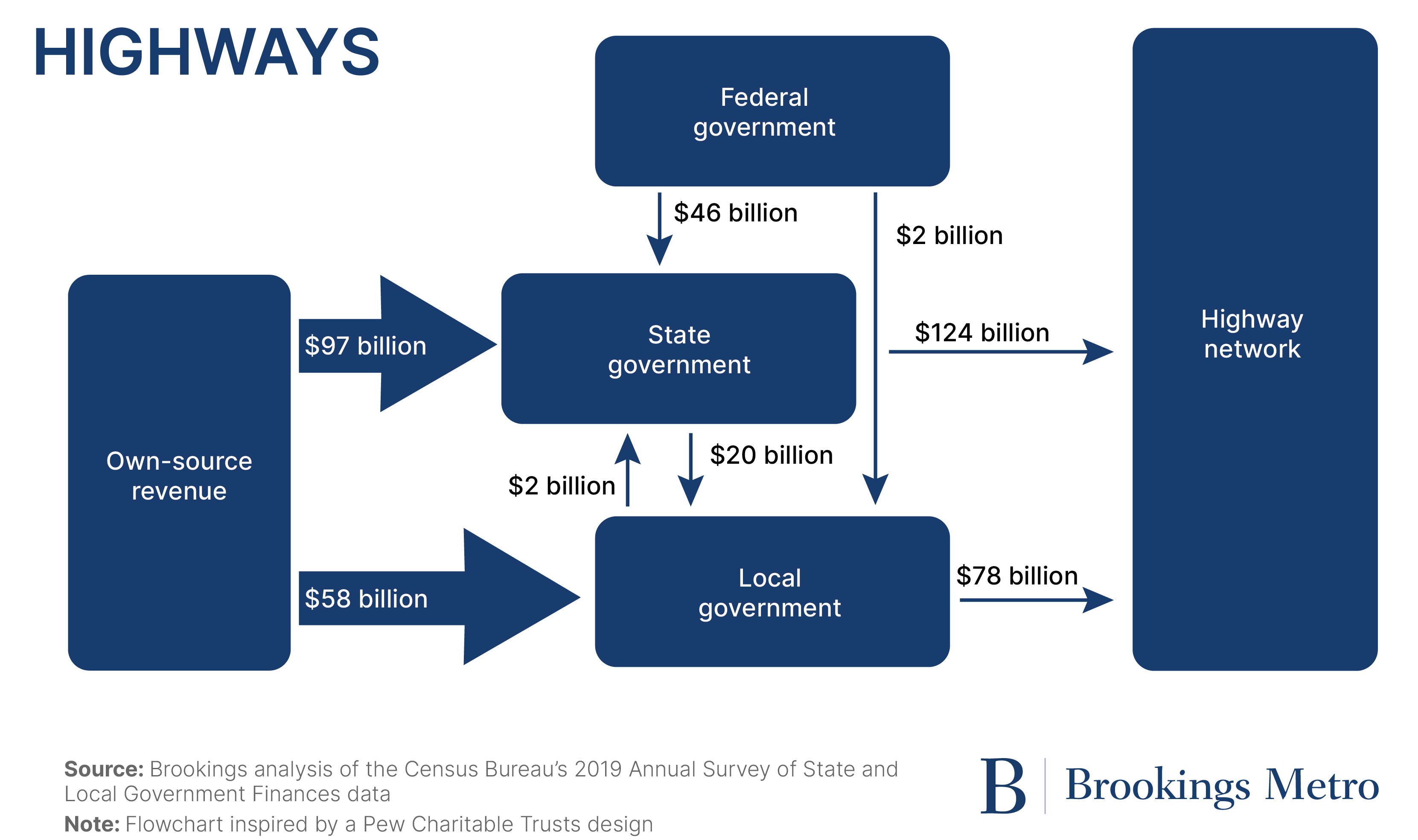

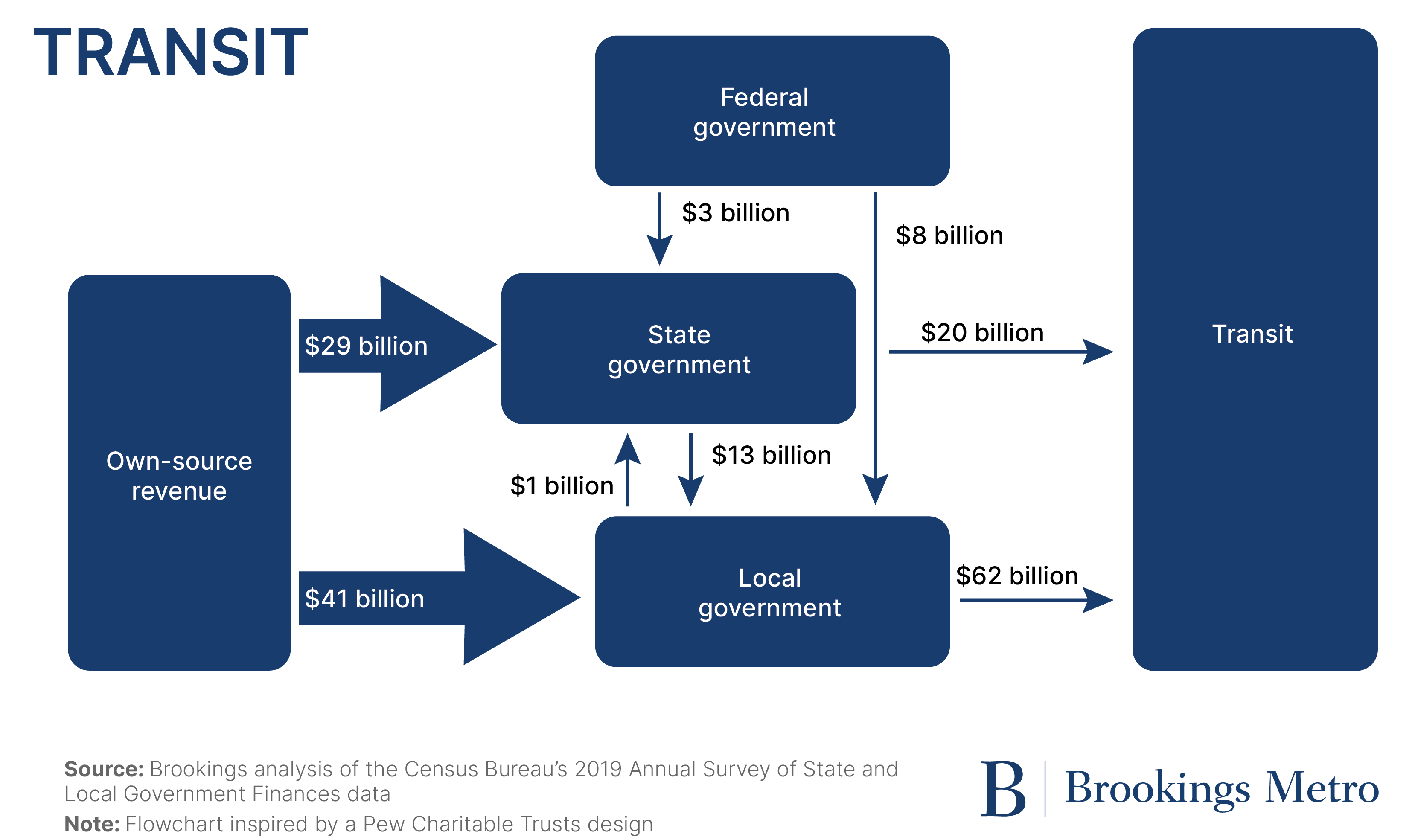

States also control or influence an outsized share of total public spending (Figure 1). The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) sent roughly $61 billion directly to states via formula funds in fiscal year 2024—or roughly 42% of total agency spending—plus additional funding, such as $7.3 billion in intercity rail grants. States raised even more own-source revenue, including roughly $145.8 billion in gas taxes, tolls, bond proceeds, and other revenues in 2019.3 That same year, states transferred $18.2 billion of their own-source funding to local governments just for roadway use, to say nothing of suballocation of federal roadway dollars or additional transfers for other transportation modes.

Yet states do not regulate, own, or invest in isolation. Cities, towns, counties, and regional governments all share those responsibilities. Local-serving governments are also, by their very nature, situated more closely to the households and businesses that use their specific transportation assets. With each municipality and metropolitan area facing such a wide array of transportation challenges—from designing safe corridors to protecting against flooding—it’s often localities and regions who are best suited to determine project priorities. For example, if a state-owned road also functions as a city’s main commercial corridor, localities may best understand how to use design features such as vehicle speeds and sidewalk width to promote pedestrian safety and real estate development.

To summarize, states wield enormous regulatory authority and fiscal powers to determine what transportation projects get built, where, and for what reasons. A more accountable state, then, is one that is willing to collaborate with its local and regional partners to set project priorities, publicly explain why decisions were made, and solicit feedback to improve future decisions.

Unfortunately, evaluating state accountability is challenging. While federal law requires states to draft Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plans—which set two-decade goals to inform future projects selected for investment—there is no published information to judge progress against federally mandated long-range goals or how state DOT staff respond to public comments on their draft plans. Federal law doesn’t require state officials to justify which projects receive funding. Nor is it obvious how much input or oversight state legislatures, independent commissions, or even the concerned public can exercise over planning and project selection.

Simply put, it is difficult for the public to hold state DOTs accountable for the transportation planning and investment actions they take. Considering the sheer size and authority of state DOTs, a lack of accountability is a pathway to eroded trust among the public and a temptation for irresponsible project priorities among DOT staff.

This report attempts to address these information gaps. We have designed a systematic approach to consistently inventory how each state conducts long-range planning and project selection, with additional attention paid to how well those practices support local governments. We also prioritize studying how the public can provide input and oversight for those processes. Finally, we include descriptions of specific state practices throughout the findings, especially those that boost transparency and local collaboration. The results offer a new way to assess state DOT accountability, the federal laws that govern state DOT actions, and how well states are willing to uplift the needs of their local partners.

Short methodology

This report involved a detailed inventory of the stated practices of departments of transportation in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. We took an iterative approach to generate a schema of transportation plans, processes, and decisionmaking practices. Interviews with key stakeholders informed our initial schema, which was presented to other interviewees. After it was finalized, we executed our schema through an inventory between late December 2023 and June 2024.

We relied on publicly available data from each state to inventory their practices within that schema. Data was primarily collected from public documents on each state’s department of transportation site. These materials principally included documents that federal law requires states to produce, including Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plans (LRTP), the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), and Transportation Asset Management Plans (TAMP). We also included state-level investment strategies, dashboards, reports, visuals, and other published content. Materials from other state agencies, governors’ offices, relevant stakeholder groups, and state statutes and administrative codes were used where appropriate to ensure the completeness of our data in representing the totality of each state’s efforts.

Given the critical importance of transparency, our strict reliance on publicly available materials is more than a methodological approach. Without relying on practices as reported by state DOTs and in absence of special access to internal processes, our inventory both describes what practices are public and clearly identifies gaps in transparency. However, given the approach to measure transparency, we take all state DOT statements in good faith. If a state DOT said they rely on asset management principles, for example, we recorded “yes” to that question. Despite our deference to state DOTs, our research may not have uncovered all relevant plans, policies, procedures, or resources. We invite state DOTs and other stakeholders to submit those.

Finally, we conducted a series of interviews to enrich and validate our data. Once we had completed our schema across all 50 states and Washington, D.C., we conducted interviews in nearly every state. In some cases, data was adjusted based on these interviews, and the report text includes anonymized feedback in key instances. A full methodology is available for download in the Appendix.

Long-range planning: States have clear goals, but measuring progress toward those goals is often imprecise and inaccessible

Transportation infrastructure is complex and multimodal. That’s something Congress recognized when they passed the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), which required state DOTs to prepare Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plans (LRTPs)—something Congress saw as in the national interest. These plans give state DOTs the opportunity to see their networks in their entirety and consider trends and investment needs over decades. Critically—and unlike metropolitan planning organizations’ (MPOs) long-range plans or state and MPO lists of planned capital projects—state LRTPs are not fiscally constrained. In other words, LRTPs do not have to bind their ambitions by available revenues.

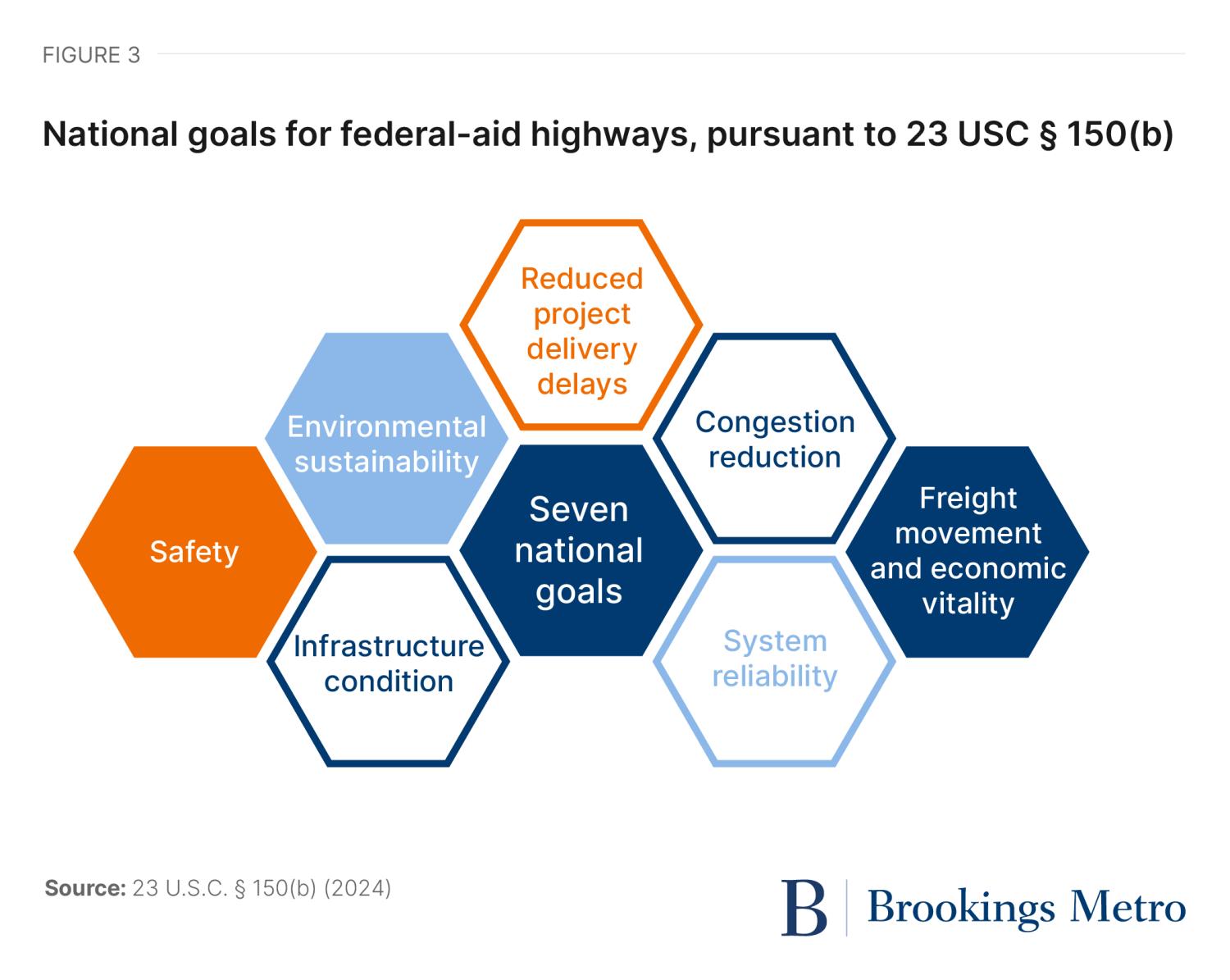

Generally speaking, state officials use LRTPs to clearly formalize the long-term goals of their transportation system. Over 80% of states include goals that go beyond the seven national goals (see Figure 3). What those additional goals actually are varies. Some have made equity a goal; others hope to achieve different forms of environmental resilience. States have articulated goals relating to land use, sustainable funding, innovative technology adoption, and quality of life. Defining equity as a goal area, for example, South Carolina aims to “manage a transportation system that recognizes the diversity of the state and strives to accommodate the mobility needs of all of the state’s citizens.”

Because LRTPs are just policy documents, most state DOTs are not actually bound to their goals. Not so in Washington and Minnesota—two states where legislatures have codified their long-range transportation goals into state law. While Washington borrows the federal goal areas with some minor changes, Minnesota adds specific goals about reducing greenhouse gas emmissions from transportation and increasing the percent of trips made on foot, bicycle, and transit.

Almost every LRTP also considers operationalizing these policy documents, with 47 states associating implementation strategies with each high-level LRTP goal. At the very least, these LRTPs give objectives: specific outcomes they hope to achieve relating to each goal. Consider Wisconsin’s DOT, which aims to “emphasize system resiliency to reduce repair costs and improve safety and security” in support of its goal of maximizing the resiliency and reliability of the state’s transportation system.

The most exemplary long-range planning efforts get even more specific, including action or implementation steps—not just strategies—for each goal. Specific technical and policy actions function as an increased measure of accountability, enabling the public to hold a state DOT accountable to its promises. For example, Maryland includes an appendix to their most recent LRTP, “2050 MTP Action Plan to Implement the Strategies of the Playbook.” Not only does this action plan link each goal’s objectives to specific actions, but it also details which agency or external partner is responsible for implementation. California has similarly specific action items and publicly tracks their completion in a dashboard.

Though most states set robust goals with some implementation element, they do not measure performance against these goals nearly as consistently. Only 27 of all state DOTs associate performance measures with each goal in their LRTP, and another 14 associate measures with only some goals in their LRTP. Yet even in those 41 states that articulate performance measures, only 15 set targets for all of them. (See Table 1 for cross-tabulated results.)

Oregon and Rhode Island offer performance measures with long-term targets for each LRTP goal. Oregon’s most recent LRTP uses indicators such as “increase multimodal travel” to track implementation progress. These indicators are umbrellas for several performance measures. For example, progress on the “increase multimodal travel” indicator is measured through transit service levels and the percentage of urban households in mixed-use areas. An improvement on that indicator would show progress toward their economic, community vitality, and mobility goals. Rhode Island’s LRTP performance measures directly relate to each goal, listing baseline 2020 performance and a 2040 target.

Yet across the board, states do not publish data on all their performance measures—a gap that limits the ability to measure a state DOT’s progress against its LRTP goals. Only ten states make data on all LRTP performance measures publicly available. Another 26 state DOTs publicly track progress on at least some of their LRTP performance measures, meaning five states that include performance measures in their LRTP don’t make their data available at all. There are also seven states that report on performance measures separate from their LRTP.4

Minnesota and Missouri are on the cutting edge of performance measurement. Since 2005, Missouri has used “Tangible Results,” a set of outcomes now linked to each LRTP goal. It publishes the performance measures used to assess progress on the Tangible Results through the Missouri DOT’s Tracker—a dashboard that’s updated quarterly and clearly states whether the state has met its target performance for each measure. Minnesota’s DOT publishes an equally robust dashboard aggregating all performance measures enumerated in its LRTP. Much like the state’s transportation goals, state law requires the Minnesota DOT to report on its performance annually.

Project selection: States take advantage of vague regulations to make investments that are detached from long-range goals

DOT staff don’t just draft plans for their states—it’s also their job to convert their long-term goals into physical projects and other transportation spending. They do that first by “programming” funds—i.e., dividing them up across different purposes and desired outcomes. Then, staff will select projects for each mode or function until they hit the maximum amount of dedicated funding.

When surveying how state DOT staff make project-level investment decisions, states typically detach the programming of funds from their long-range planning and performance—a disconnect that enables state DOTs to invest in projects without aligning their spending to published goals and performance targets.

To the extent that the federal government regulates the project selection process, it does so through the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP). Federal regulations require the STIP to include a prioritized list of capital and non-capital surface transportation projects that are either: 1) proposed to be federally funded; or 2) regionally significant but not federally funded.5

State DOTs have a few clear requirements as they assemble their STIP. Federal regulations mandate that each MPO’s unchanged Transportation Improvement Program (TIP)—the prioritized projects within each metropolitan area—be directly incorporated into the STIP. State DOTs must also develop their STIP “in cooperation with” each MPO, although without clear benchmarks. Finally, state DOTs must provide certain information about each project, including technical details, total cost, obligated federal funds, and the agency responsible for execution.

As for the “why” of a project’s inclusion in the STIP, however, state DOTs do not need to include a justification. Federal regulations only require that each project or project phase be “consistent with the long-range statewide transportation plan” and, for projects in metro areas, consistent with the MPO’s long-range plan. It also requires, “to the maximum extent practicable,” that the program include a discussion of how the STIP might affect the state’s achievement of performance targets set in its LRTP or performance-based plans.

Practically, sparse regulations like these are what enable states to de-couple planning efforts and project selection. Not surprisingly, less than half of states include some mechanism to tie their STIP or Capital Plan back to the LRTP. And even among this group, there is extreme variation in the depth and transparency of these connections.

States with the deepest and most transparent connections tend to connect individual projects to specific LRTP goals, linking the long-range plan to the actual project implementation processes, including environmental studies, programming, funding, and construction. For example, Maryland’s Consolidated Transportation Program—the state’s six-year capital budget for transportation projects—lists the LRTP goal that each major project supports and includes a paragraph explaining how the project advances that goal. Colorado and Utah ely on their LRTPs to produce long-range lists of projects—a truly unique approach among their peers.

Other states tend toward specific but more superficial references. In Tennessee, each project in the STIP includes a “Long Range Plan #” which denotes the LRTP goal associated with the project—but there is no further written justification. New Hampshire and Idaho differ only slightly, listing the federal performance measure each project aims to address.

There’s another hybrid-like group of states that tends to use “investment strategies” as proxies between LRTP goals and actual project selections. Since 2009, state law requires Georgia’s DOT to publish the Statewide Strategic Transportation Plan (SSTP), a set of long-range investment strategies. The SSTP is now integrated into the state’s LRTP updates, solidifying the state’s performance-based approach to investment. In Montana, LRTP goals are a key input of the Px3 process, which DOT officials use to allocate transportation funds and evaluate the performance of projects in the STIP. Wyoming took a different approach, leveraging their most recent 2010 LRTP update to identify 16 critical corridors in the state. This broader effort, called Wyoming Connects, uses the LRTP as a foundation for each corridor’s vision and strategy.

Still, that leaves over half of states with no demonstrable connection between their LRTP and STIP or Capital Plan. Despite the U.S. code requesting a state’s STIP be consistent with the LRTP, 45% of states (29) don’t even meet this threshold. Among those states, the vast majority (23) write only generalized text to confirm their STIP aligns with their LRTP (see Box 1). There are another six states that don’t include any such reference at all.

Box 1. Excerpted statements of alignment between LRTPs and STIPs

“The various types of multimodal projects in the STIP are prioritized and programmed to achieve the LRTP goals and the national performance measure goals.” -South Dakota

“The projects identified for funding by each program have been thoughtfully selected through performance-based planning selection processes in order to ensure the operation, maintenance and improvement of Ohio’s robust transportation system. The projects are consistent with the goals of Ohio’s Long-Range Plan (AO2045) and align with the priorities to take care of the current transportation assets before considering expansion.” -Ohio

“STIP projects must be consistent with each county’s long-range plan and/or the Statewide Transportation Plan (23 CFR 450.216(k)).” -Hawaii

A far bigger concern in terms of programming, however, is how actual projects are selected. Here, an even smaller group of 18 states executes public-facing project selection systems that allow stakeholders—including the public—to understand why specific projects were chosen to receive funding.

Among the comprehensive processes, Smart Scale in Virginia is perhaps the most publicized. Virginia’s Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) uses Smart Scale to source, evaluate, and prioritize projects that address their “Mid-Term Needs.” Regional entities, localities, and transit agencies can submit projects across modes. Those projects are then evaluated against metrics related to six goal areas, which are weighted differently depending on where in Virginia the project is located. Those scores are made public, then used by state staff and the CTB to create the Six-Year Improvement Plan.

Less publicized, Kentucky has prioritized roadway projects on its SHIFT system since 2018. Officials at various levels of government add—or “sponsor”—projects to the state’s database of transportation needs. Projects addressing those needs are scored on a series of metrics evaluating different attributes, and projects of statewide significance are selected by state DOT staff first. SHIFT then allows local transportation officials to boost the remaining projects, adding points to those they received as part of the DOT’s initial scoring. SHIFT results in each of the state DOT’s 12 highway districts having their own prioritized list of projects. But this process isn’t without its limitations: The number of local “boosts” and “sponsorships,” as well as the funds available to be spent across prioritized projects, are not allocated proportionally to each district by either their population or their VMT.

Virginia and Kentucky aren’t alone. North Carolina’s Strategic Transportation Investments Law established its Strategic Mobility Formula and Project Prioritization Process, which stakeholders in states with no public process often look to. Arizona’s P2P process has clear criteria and weighting to score projects. Minnesota has a process for highway projects; Vermont has one for highway and bridge projects, with other modes yet to be implemented; Ohio, Utah, and Illinois publish their prioritization processes for projects that expand system capacity, and the former two states use independent entities to help govern the process. Yet even within that group of 18 states, there are gaps. Multimodal evaluation is still a rarity, and many states don’t even evaluate their highway capacity and maintenance projects together.

As a state’s transportation ambitions and needs change, it’s important that the public can know the year a project was added to the STIP—and be able to use that time-based benchmark to confirm staff aren’t holding on to projects that no longer merit investment. Here too, states struggle to offer transparency.

Even though projects are always being added and taken off STIP project lists, only one state clearly documents the year in which a project was added: In the individual description of every project, Nevada’s e-STIP includes a full history of additions and amendments. A couple—Georgia and Oregon—include the year in which preliminary engineering began or funds were authorized for a project. While these might be the year some projects were added, that’s not safe to assume across the board. South Carolina includes a “rank” for each project with a year in it, but it’s again unclear whether that’s actually the year the project was added.

However, there are actions where all states are successfully communicating project selection processes to the public. Asset management plans—a new federal requirement in 2012—are now being used in every state to report the condition of National Highway System (NHS) pavements and bridges, and identify investment strategies that would improve those conditions (see Box 2 for more details).

Box 2. TAMPs: What they are and why they matter

When the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) became law, Congress consolidated multiple programs into the National Highway Performance Program (NHPP), which would then distribute nearly two-thirds of all federal-aid formula dollars.6 In an effort to bring more accountability to NHPP spending, Congress also required states to create their own Transportation Asset Management Plans (TAMPs) with some specific requirements.7 At minimum, TAMPs must include the state DOT’s asset management objectives, measures, and targets for asset condition, and a description of the condition of NHS pavements (regardless of ownership).8 State DOTs must also include investment strategies—based on their analysis and asset management—that would support improving asset condition and achieving performance targets and national goals. Perhaps most critically, states are federally required to integrate their asset management plans into transportation planning processes that lead to the STIP.

Per our research, every state DOT is meeting those federal requirements. Each TAMP includes all NHS assets, regardless of ownership. Every TAMP at least mentions that its analysis, targets, and strategies inform project prioritization; many stakeholders we interviewed said that TAMPs were among the most important documents in project selection and prioritization.

Yet the exclusive focus on NHS roadways within the original NHPP reforms may be limiting what TAMPs can deliver. While federal law encourages states to include public roads outside the NHS, nearly half (21) of state TAMPs include only the minimum NHS pavement and bridge assets. And of the 30 states that have gone beyond the NHS, they tend to only expand their assessment to the state highway network—not locally owned streets or other modal assets. And per related research, states simply continue to not collaborate with their local partners as much as they could.

The Maryland and Minnesota DOTs demonstrate the ability to monitor more. Both states consider facilities, tunnels, and IT systems as additional asset classes. Minnesota also includes pedestrian infrastructures—primarily sidewalks—and Maryland’s DOT evaluates their vehicle fleet and equipment. Both states can serve as examples for other states to expand their TAMP approaches.

Local collaboration: States rarely plan or invest in ways that meet the needs of regional and municipal partners

Every statewide transportation network relies on balancing the needs of both local and longer trips. That necessitates a collaborative planning and investment environment—one that reflects the complementary specialties among states, MPOs, and municipalities. For example, state officials are ideally suited to promote interstate commerce, while localities better understand the ambitions and needs of residents. But with states standing atop the administrative structure, state officials carry the burden to help localities construct the projects their communities demand.

Unfortunately, most state DOTs have erected planning and investment barriers between them and their regional and municipal partners. Metropolitan planning is one clear gap. Federal law requires states to develop their LRTP “in cooperation with affected MPOs,” but with limited specificity around standards.9 There is no requirement to ensure a state’s LRTP reflects the exact project priorities detailed in MPO planning and investment documents. Instead, state DOTs are given wide latitude to determine how they seek input and alignment with metropolitan plans. (Note: Rhode Island is not evaluated, as a single MPO covers the entire state and exists as an executive agency.)

Only two states—Colorado and Utah—rely on the projects and priorities enumerated in MPO long-range plans to develop their own long-range project lists. In their most recent LRTP updates, both states used their new plans to produce decade– or multi–decade long prioritized project lists to implement their plans. And, in both states, DOT officials sourced projects on those lists in part by deferring to the long-range planning done by their regions’ MPOs. From design into practice, these two states use a formal deference to the long-range goals and projects of their regions when they do their own long-range planning.

The other 48 states do not rely on metropolitan plans to implement their own statewide vision in as nearly a clear-cut, demonstrable fashion. Given that gap, most DOTs only connect statewide and regional long-range planning when they collaborate on state LRTPs—though the quality and breadth of that collaboration vary significantly. Nebraska’s LRTP simply notes that its Stakeholder Advisory Committee included a representative from one of the state’s four MPOs. South Dakota’s LRTP calls MPO plans “integral” and says that they are included in the planning process, but does not say how. In Oregon, according to in-state experts, the state’s long-range planning process does not add to or unify MPO long-range plans, and instead requires the regional plans to conform to the state’s. Oregon is not unique—experts in many states experience a similar dynamic.

Most troubling, interviews found multiple instances in which state DOTs forced MPOs to update their long-range plans so the state could develop a capital project that was not in original alignment with those plans. This is consistent with academic findings reported across several decades. While we have not scored this practice in this report, “jamming” projects into carefully crafted and fiscally constrained regional plans is troubling enough. Not only would it violate the spirit of state-MPO collaboration, it also could burden MPO staff to formally amend their plans for fear of fiscal retribution by the state.

Box 3. Utah’s approach to regional collaboration

Though there are gaps between many MPOs and state DOTs when it comes to collaborative planning and investments, there are places that stand as models of a closer, healthier relationship between state and regional leaders. This is certainly the case in Utah, where the state DOT’s most recent long-range planning effort culminated in the 2023-2050 Unified Transportation Plan. This plan is produced when each of the state’s various entities responsible for transportation planning—four MPOs, Utah’s DOT, and the Utah Transit Authority—conduct their respective four-year planning efforts. The agencies come together to agree on shared time horizons, revenue and cost estimates, modeling approaches, GIS schema, performance measures, and communications, which allows for a careful and efficient plan to distribute resources across the state.

Utah’s Unified Transportation Plan covers all modes of transportation; it plans for new capacity to accommodate growth, as well as operations, maintenance, and preservation needs. The processes by which the MPOs and the state DOT collaborate are exemplary. Utah’s residents and visitors benefit from decades of work to align state, regional, and local leaders around the intersection of land use and transportation investments. Today, durable relationships, consistent communication, and the Unified Transportation Plan process help put such alignment into practice. Peer states and metro areas can apply these lessons as they consider formal planning reforms and everyday approaches to staff- and executive-level communication.

Funding is a far more egregious barrier between states and their local partners. Based on a review of budgets in each state, the average state suballocates only 14% of their total funding to local partners. Suballocation, in this case, refers to money that’s given directly to sub-state governments—e.g., cities, counties, MPOs, etc.—to execute their own transportation projects. Programs such as state-run discretionary grantmaking and local public agency funding—where the state DOT still retains ultimate project authority—are not counted. To put that budgetary share in context, it’s less than half the size of VMT (a proxy for federal and state gas taxes collected) on non-state-owned streets.

Yet this average is impacted by many of the outlier states with the largest suballocation rates. By contrast, the median share of total suballocated funding is just 8% (see Figure 5). Looking at the overall distribution, 26 states suballocate less than 10% of total transportation funding, with 15 failing to break even 5%. There is no universal pattern to where suballocation is lowest, although southeastern states disproportionately send the least formula-like funding to their local partners.

Yet there are states where suballocating to local partners is the norm. In five states, at least 35% of total transportation revenues is passed down. These states—Minnesota, Oregon, Michigan, Iowa, and Arizona—are in different regions, exist in different partisan environments, and have different levels of urbanization. Despite these differences, each makes a clear effort to empower localities. When a state financially supports its local partners, it is supporting a more balanced investment across local- and state-maintained roads in all areas of the state.

Public involvement: States can do more to educate nongovernmental stakeholders and enhance their participation in transportation planning and investment

Statewide transportation planning and investment is an obtuse process, and especially so for stakeholders who don’t bring advance understanding of transportation governance. For example, it’s unreasonable to expect business executives and nonprofit leaders to learn project permitting processes or federal requirements for statewide planning. The burden is on state DOT staff to help their nongovernmental stakeholders understand how the agency chooses long-range goals and connects those goals to project selections.

One area where most state DOTs do well is aggregating programmed projects into a publicly accessible portal. Forty-four states have such a site (see Figure 6). Some map every project, while others keep a more straightforward list. Kentucky, for example, visualizes projects prioritized through its SHIFT program. This visualization goes beyond basic engineering specifications for each project, including its cost and score on each SHIFT metric. Additionally, many states specifically visualize their STIP or capital plan. Michigan’s DOT has a portal that maps projects from their STIP, 5-Year Transportation Program, and the $3.5 billion Rebuilding Michigan bond program. Though the level of details in these portals vary widely (e.g., North Carolina breaks down projects by mode and owner, while Vermont just separates them by their anticipated construction year), state DOTs generally deserve recognition for their efforts to make project information more accessible.

When it comes to publishing information on state-run funding programs, state DOTs generally make that information easily accessible. Thirty-nine state DOTs aggregate their local funding programs in one place; among the 12 states that don’t, most at least have some webpage with local-funding-related information. Massachusetts’ DOT has a portal aggregating its nine state-run funding programs, and has the notable inclusion of a short survey that can match a user’s desired project to a program. Oregon’s DOT portal lists the date each program began accepting applications, eligible applicant entities, and whether local match is required. California’s DOT has a Division of Local Assistance, with a website that includes both a simple list of funding programs and a robust set of documents, forms, and processes that are relevant to local leaders.

Yet despite these achievements, states could still do more to educate and promote participation among nongovernment stakeholders.

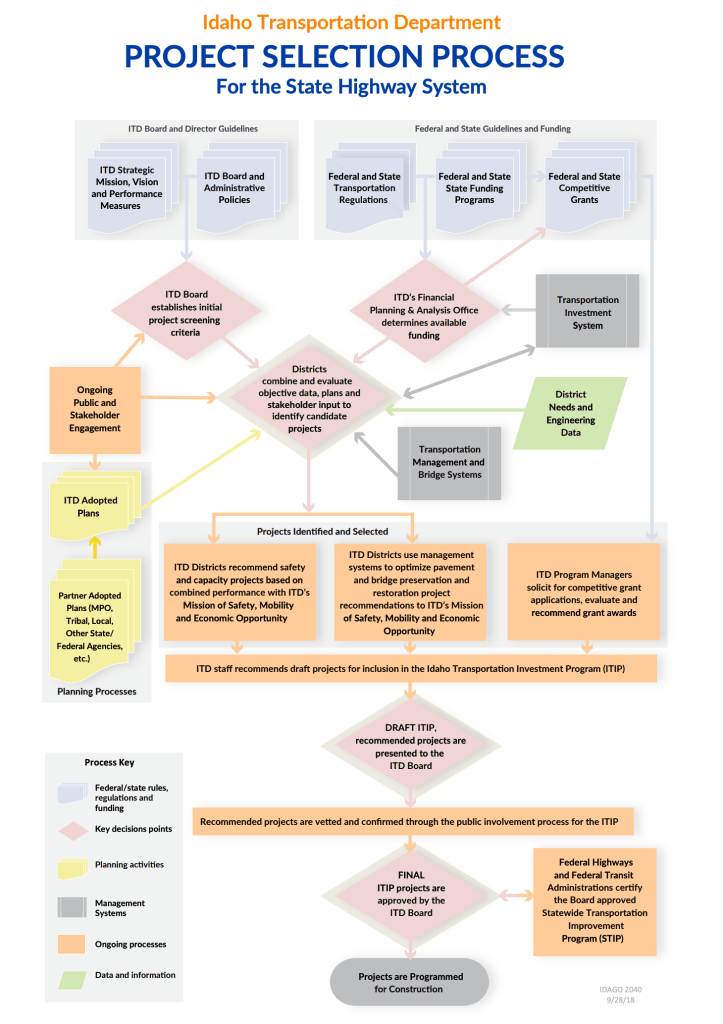

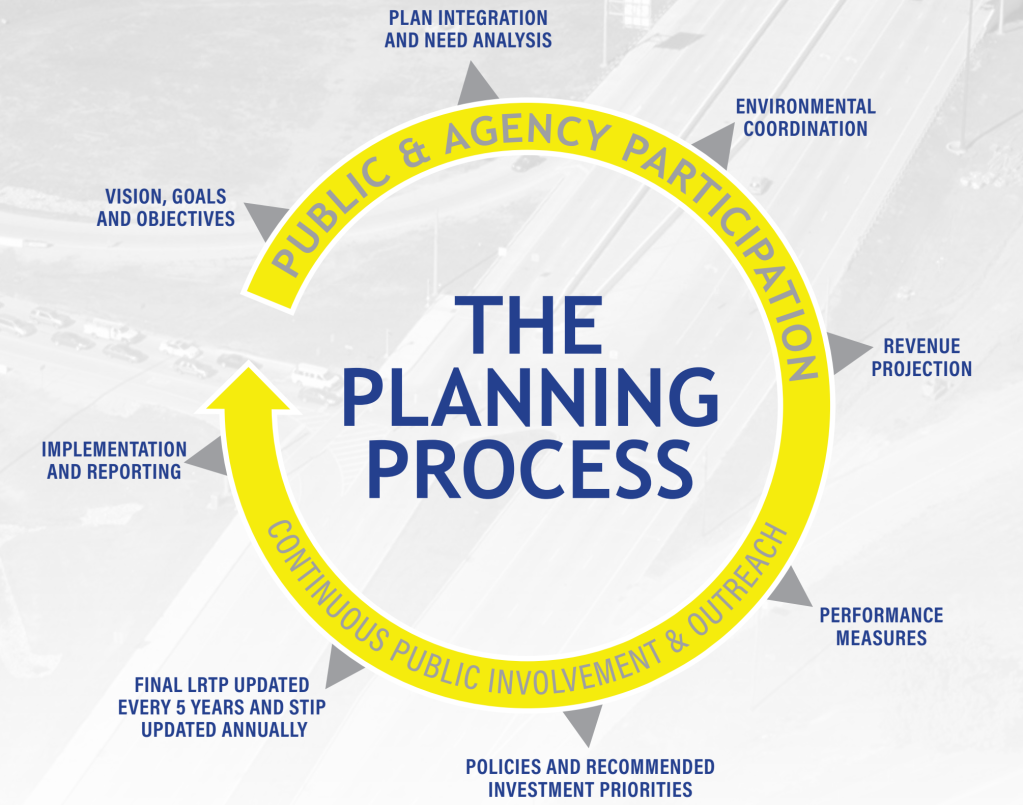

One typical gap is the lack of a flowchart or other visual document to explain the state DOT’s planning and project selection processes. Twenty-three states have a robust visualization of those processes, while 17 others only visualize one process or lack detail. The Idaho Transportation Department, for example, published a flowchart documenting its decisionmaking process for its state highway system (linked below). Though the flowchart focuses on the project selection process, it also identifies various plans as inputs to that process. The flowchart’s “process key” also shows stakeholders key decisionmaking points—information that is crucial and often painfully inaccessible. Visuals with fewer details can still be a significant aid to the public and nongovernment stakeholders. Pennsylvania’s DOT explains its planning, programming, and performance measurement processes and their interrelation. Maryland’s DOT visual is relatively simple, documenting the flow from LRTP to STIP, but it shows which steps allow for public input.

Some visuals, however, provide no significant information, or lack detail to the point where it may limit utility for the user. The only planning- or project-selection-related visual across Indiana’s DOT publications identifies several steps taken during long-range planning (linked below). But these steps are generic, leaving stakeholders with little understanding of how the DOT actually executes the various planning processes or where the agency would accept public input.

Most states also fail to host a portal that solicits input from the public. While many states have such websites for individual projects, only 37% aggregate those public comment opportunities. Of the 31 states that don’t have that kind of portal, 27 at least list upcoming meetings in one place. There are positive examples, though: Wyoming’s DOT portal maps all projects on their STIP and accepts comment; Maine’s DOT portal aggregates all open and closed project comment periods; and North Carolina and Virginia use the same software to navigate easily between surveys, projects, and meetings.

One area to boost public transparency is by improving public data from statewide asset management systems. Only 22 states publish a geospatial dataset with detailed information on conditions for both pavement and bridge assets (see Map 2). Most of those 22 state DOTs publish the conditions of both NHS and state highway assets. Maryland lets users see the roughness, cracking, and remaining service life of all its NHS and state highway pavements. West Virginia may include fewer condition performance measures, but users can filter to a specific MPO or DOT highway district and see summary statistics for the jurisdiction’s pavements. Publishing more detailed data and maps could serve as a foundation for more precise dialogue between state officials and nonexpert stakeholders around where to channel public investment dollars.

Independent bodies: Most states establish independent commissions to support their DOT operations, but their governance structures and legal authority vary widely

Independent commissions are a well-respected approach to bring public input and oversight to American governance, including in transportation. Such commissions offer a way to bring experts from various fields—in transportation’s case, a mix of engineering, real estate, industry, and environmental studies—to serve as public liaisons and, critically, as voices not beholden to current state governing coalitions. Independent commissions are also flexible in terms of task: able to do everything from more abstract brainstorming around long-range goals to highly specific evaluation of project selection.

Based on a national scan, such independent commissions are a popular tool within statewide transportation governance. The concern is that many states are not tapping their full potential.

For example, most states used a commission or similar group to inform or judge statewide planning strategies, but their responsibilities vary considerably. Twenty-six states have a permanent board or commission as part of their DOT governance, 22 of which played a demonstrable role in approving or judging the state’s LRTP. Another 13 states convened a group of stakeholders to inform the LRTP’s development, although they were not a permanent board or commission. The Florida Transportation Commission is an example of the former, set up to “function independently of the control and direction of the department [of transportation].” Florida statute requires them to hold at least four public meetings a year and review plans the department produces for the governor. Ohio has no analogous commission, but in their most recent LRTP development process, they convened a steering committee with representatives from the state DOT, regional planning agencies, cities and counties, business and economic development organizations, and environmental and community interests.

An independent body that advises the legislature on spending practices is another popular option, although these also vary in their organizing principles and responsibilities. The predominant approach in 49 states is to use professional staff within the legislature. However, in nine of those states, the department or office housing that staff doesn’t explicitly identify itself as nonpartisan, independent, or impartial.

That leaves two states with no such entity. The first is Hawaii, where, technically, the Office of the Legislative Analyst has been authorized to exist in the state legislature since 1990. Since its originating statute became law, however, the state legislature has never funded it. Second, in Massachusetts, the General Court never passed the first hurdle; legislation to establish a Legislative Fiscal Office died in committee as recently as 2023.

Most states (33) also have entities that oversee project selection, programming, or contracts in some way, and responsibilities continue to vary from state to state. On the more expansive end of the authority spectrum, the California Transportation Commission was established to oversee allocation of funds across highways, passenger rail, transit, and active transportation. In Ohio, the Transportation Review Advisory Council is a legislatively authorized body with a much more narrow purview, overseeing the selection, prioritization, and approval of projects in the Major New Capacity Program; members are appointed by the governor and majority leaders in each chamber of the state legislature.

Finally, there are boards and commissions set up to review the fundamentals of a state’s transportation funding. In very few states, there are entities that have been established to review how the state funds transportation. Massachusetts recently initiated the governor-established Transportation Funding Task Force, and the Maryland Commission on Transportation Revenue and Infrastructure Needs includes 31 members spanning government at all levels, business, advocacy, labor, and more. In both cases, the impact of their recommendations still depends on legislatures enacting relevant changes.

In Illinois, the Blue-Ribbon Commission on Transportation Infrastructure Funding and Policy has been tasked with what amounts to a review and evaluation of nearly all aspects of transportation in the state. Members are considering current and future funding options, transportation governance, and how to expedite project approval and completion. They’re evaluating the state DOT’s workforce and data needs. They’re assessing how to improve the impact of transportation investment on emerging goal areas such as climate and equity, honing in on the state’s performance-based programming system. Perhaps most importantly, the Commission is tasked with considering alternative solutions other states employ.

Box 4. The legislative puzzle piece

Legislatures have an enormous role to play in governance of a state’s transportation system. While the state DOT charts the course for the future of transportation—whether on a 20-year planning horizon or at mere tenths of a mile on the interstate—their power is not inherent. State legislatures authorize the existence of their state DOTs and then pass laws to define their roles and responsibilities. In a sense, the legislatures have the authority to design and build the car—state DOT staff are just in the driver’s seat.

Yet for all their import, it’s challenging to judge legislative approaches. There is no “correct” approach to how those bodies govern transportation, and there is plenty of variation between states. Thirty-one pass state budgets annually, while the other 20 do so biennially. Maryland uses a “strong executive model,” which means the state legislature can only cut or restrict funds in the budget the governor proposes. All of Utah’s state legislators are involved in the appropriations process; each member serves on at least one appropriations committee.

Some legislatures have taken more active roles in governing transportation. These differences often play out in the specificity of appropriations bills. South Dakota, for example, appropriates DOT funds in two simple categories: “general operations” and “construction contracts – informational.” Alaska, on the other hand, incorporates the entire Statewide Transportation Improvement Program, project-by-project, in its state budget and appropriations bill. According to our interviews, this level of involvement can impair DOT governance in some cases.

Some of the most involved legislatures have cemented common DOT procedures or policies into their state code. Legislators in Washington codified their state’s transportation goals, instructed various agencies and commissions to collaborate on objectives and performance measures, and required that the state DOT submit a biennial report to the legislature and governor on attainment of its goals. Wisconsin lawmakers defined, in specific terms, the process and criteria that should be used to evaluate candidates for major highway projects.

Legislators from different states will naturally take different approaches to transportation governance. More involvement is not a success or failure per se. Instead, it’s the role of all stakeholders to understand how their legislature works. If it appears the legislature could improve outcomes by adjusting how they govern, this survey offers a collection of national practices to consider.

Implications

State DOTs and their staff have enormous responsibilities to manage America’s expansive transportation network. They raise and spend almost half of the over $300 billion of capital invested in the network each year. State officials must report-up to their federal colleagues, preparing long-range plans and stewarding tens of billions of dollars in formula funding. They also must forge partnerships with their local colleagues to co-design safe and economically competitive communities. It’s not an exaggeration to say state DOTs are the hub of American transportation governance.

States frequently present an image of public accountability to carry out these responsibilities, often going beyond federal law. Almost every state’s LRTP includes generalized implementation plans to achieve each major goal. Almost every state hosts a public portal to communicate details related to every project they’re building, and most states include an option for the public to submit comments on those projects. A clear majority of state legislatures authorize independent commissions of some kind.

Yet in practice, most states develop plans, select projects, and commit funding with little functional oversight and often minimal collaboration with their local partners. Too few states link their selected projects to either long-range goals or public-facing selection methodologies—a known gap for at least a decade—and states rarely publish evidence for how public comments or statewide meetings impact their project selections. Only two states demonstrably use their MPOs’ projects to inform the state’s long-range plans. Maybe most troublingly, the average state suballocates less than 15% of total funding to regions and localities—far less than even the gas taxes collected from VMT on locally owned streets.

These patterns are not an accident. Legislators, governors, and federal officials have failed to adopt laws and policies that compel greater public accountability and responsiveness to local transportation needs.

While it makes sense for legislators to defer to the civil engineering expertise among DOT staff—particularly as it relates to system maintenance—those individuals are elected to office to ensure DOT-funded projects advance long-term goals such as economic competitiveness, resilience, and public safety. Laws to require transparent project selection methods, goal-oriented performance measurement, and lifecycle project costs would all help legislators meet their oversight obligations. Independent commissions are a well-established platform to support such evaluation (while not increasing legislators’ personal duties), but most legislatures have not chartered commissions to host critical debate, and almost no states have independent commissions that consider budget resources, judge project selection, and monitor performance all at the same time.

Governors and their cabinet members miss their own opportunities to more closely align an administration’s ambitions with the specific actions of their DOT colleagues. Simply put, most states’ long-range plans don’t impact project selection. For example, fewer than half of states demonstrate how the long-range goals within a LRTP will affect future funding decisions. Even worse, only nine states use complete performance measures to monitor progress against each of their long-range goals—making it difficult to track how projects impact goals.

Legislators and governors also fail to require bidirectional communication pathways between the public and state DOT staff. Once a project is on a STIP, it’s seemingly impossible for civic organizations to provide feedback on how the project would impact the communities they serve. Likewise, there’s no obvious mechanism for those organizations to share what communities need before projects are committed to in the first place. Chambers of commerce, community nonprofits, philanthropies, and their peers need simple ways to reach state officials.

The federal government is equally complicit in missing oversight opportunities—nowhere more so than in policies related to project selection. In theory, the LRTP and STIP should operate in tandem to ensure long-range planning informs project selection. But since there’s no requirement for state officials to demonstrate how each project on the STIP advances goals within a LRTP, states can functionally construct any project they’d like as long as they follow technical requirements such as environmental permitting or structural design. Federal law also allows the same projects to carry over from one STIP to the next with no requirement to list the year a project was originally added, making it difficult for the public to know what long-range goals a project aims to serve. Combined, these gaps in federal law eliminate the ability for LRTPs to create genuine accountability.

In other instances, federal law makes it too easy for states to out-muscle local needs. For example, federal law requires each state to align its LRTP and STIP with related plans drafted by MPO partners. In reality, federal law is naïve about a state’s ability to use its fiscal clout to influence what projects MPO staff choose to prioritize. Giving states deference over whether to suballocate federal funds is another functional weakness, as the data in this report confirm most states choose to hold onto transportation revenues. Even recent requirements to improve monitoring of state assets via TAMPs—a highly successful federal policy reform—benefit states, since they do not need to monitor local roadway conditions.

Recommendations

While state departments of transportation may have originally been formed to help construct highways and promote safety on those roads, their mandate has evolved. This century demands a more flexible framework to promote accessibility, safety, and resilience in every community. Expectations around accountability are now higher too. External stakeholders and the interested public rightfully expect state officials to clearly explain why they’re investing in specific transportation projects—and give them genuine opportunities to offer their input during both planning and project selection stages.

States should continue to update their policies for this new era. Fortunately, every state DOT starts with significant operational strengths. Their staff know how to put public dollars to work quickly in constructing projects large or small. State DOT leadership maintain established relationships with federal officials, particularly around fiscal accounting. Many central and regional DOT offices have built trust with their municipal partners to co-develop project strategies by committing to regular communication and even sharing staff. And most state-owned transportation assets are in good physical condition.

To build on those strengths, federal and state officials should adopt reforms that target areas ripe for improvement. Local stakeholders, including municipal officials and civic organizations, can engage with these recommendations by advocating for their adoption or implementation. Fortunately, this report uncovered many accountability-focused practices from across the country that could be considered in peer states. Using the findings and specific examples as a guide, we recommend the following reforms:

For federal policymakers:

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act’s expiration in 2026 creates a policy window to address the accountability gaps highlighted in this report. There are multiple areas of opportunity:

- Congress should update at least two requirements for state LRTPs. First, it should require that each long-range goal include a more specific implementation plan. Those implementation plans should also include a fiscally constrained list of projects—permitting project overlap across plans—that is informed by asset condition reports and specifies whether projects include capacity expansions. Second, the planning process should require more extensive collaborative work with local and civic partners. One option is to convene a LRTP review board composed of government, civic, and non-transportation industry representatives, with the governor and legislature splitting nominations.

- Congress should update two requirements within the Transportation Improvement Program guidelines. First, every state should be mandated to create a public-facing project scoring system, using quantitative data that reflects the LRTP’s goals. Both Virginia’s Smart Scale and Kentucky’s SHIFT programs offer templates to build from, and Congress could begin by requiring a pilot in each state, using the recent discretionary Prioritization Process Pilot Program as a reference point. Second, every state must include clear justifications for each project—beyond simply listing a related LRTP goal—and the original year the project was added to the STIP.

- Congress should increase direct formula funding to regional governments, which will address the unequal power dynamics between states and MPOs. Two alternatives to consider are requiring suballocation levels across multiple programs or creating a flexible regional block grant program. One benefit of increasing direct regional support is it should immediately increase the effectiveness of current laws requiring state and MPO collaboration. Greater direct fiscal support to regions also could increase potency of other federal fiscal laws, such as fund swapping.

- Congress should require every state to adopt independent commissions. As in the case of Virginia and New Hampshire, commissions can greatly enhance accountability and uplift long-term goals for the transportation system. In an effort to not limit state sovereignty, Congress should give states flexibility to determine what priorities a commission will review, including long-run cost and revenue projections, asset condition reports, project selection criteria, and cross-cutting goals such as industrial growth and housing capacity.

- Congress should adjust TAMP laws to benefit all major roadways. TAMP laws are an administrative success, but to the detriment of locally owned roads that are often in worse condition but not monitored. Expanding monitoring to all principal arterials will ensure state officials have data on all major roadways—enhancing the likelihood they’ll prioritize investment in roads irrespective of their owner. Federal law could also consider setting a ceiling on recommended roadway quality, which could help spread spending to more roadway segments each year.

For state legislators and governors:

This research revealed the starting point of each state DOT, both in terms of public accountability systems and direct community support. As elected leaders consider reforms tailored to their state’s unique transportation needs and legal circumstances, this research highlights a set of policies that could be seen as benchmarks for every state to consider. (Note: Many of these policies could also become requirements under federal law.)

- States should ensure every goal within their LRTP includes targeted implementation strategies and published performance measures. During the plan’s writing phase, every state should require input from non-state government staff, including independent commissions. This would complement public comment periods after a draft plan is published. Legislatures can also follow Minnesota and Washington’s lead and enshrine the goals within their state legal code.

- States should adopt public-facing project scoring systems. Those systems should be informed by an advisory board that works with DOT staff to consider different measurement variables. Ideally, those scoring systems should have ways to simultaneously consider multimodal projects, in the same vein as the new Minnesota state law.

- When developing the Transportation Improvement Program for each substate region, states should develop methods to ensure local and regional stakeholders have an equal voice, particularly around expansion projects. One approach to model is New Hampshire’s, where the state DOT has executed a memorandum of understanding to advance regional priority projects without changes, provided that they are fiscally constrained. Prior to finalizing each updated list, the published document should include the year a project was added and a connection to one or more LRTP goals.

- Legislatures should pass—and governors should support—the creation of independent and empowered transportation oversight commissions. Each commission should require the legislature and governor to have nominating authority, necessitate inclusion of members who work outside of government, and empower members to review the LRTP, funding sources and cost projections, and economic, social, and environmental impacts of past and future transportation projects.

- Legislators can adopt programming that increases direct funding to MPOs and localities. Current practices from states such as Arizona and California can serve as models for boosting direct funding. An additional consideration could be giving localities more additional funding to select projects, but also allowing them to transfer funding back to the state DOT if its staff can deliver projects faster and cheaper.

For state DOTs:

Finally, there are multiple steps that state DOT leadership can take on their own without waiting for federal or state guidance.

- Many of the emerging challenges that the country’s transportation system should address—including pedestrian safety, industrial site development, and protecting people from extreme heat—play out at the local level, including the need to coordinate land use and transportation policies. State DOTs should be open to shifting their state-local collaboration model to one where regional and local partners take the lead on community engagement and establishing project priorities, while state DOT staff bring their technical expertise and fiscal resources to accelerate project construction. Both can also work together more closely on performance measurement practices.

- The success of the current asset management programs—both in terms of prioritizing maintenance projects and building public trust—should inspire an expansion to monitor and report locally owned asset quality. Integrating local conditions into the statewide TAMP will give state policymakers a more holistic understanding of where investment dollars are most needed. The major beneficiaries of such an expansion would be system users. Similar to the federal recommendation, setting a ceiling on roadway quality could promote more investment in more roadway segments.

- Each state DOT can update public-facing communication practices to help external, non-transportation stakeholders better understand planning timelines and procedures. Updating procedural flowcharts on the agency website, improving public input practices, and promoting competitive grant opportunities could all build public trust and enhance DOT staff’s understanding of what communities want. State DOTs should also consider publicizing the inputs, analysis, and scores used by and generated within project selection systems.

Conclusion

America’s transportation system faces a series of structural challenges in the coming years. Roads are far too unsafe, many transportation services are too expensive, and the country’s physical assets are facing new environmental threats. Meanwhile, concentrated population and economic growth within metropolitan areas and the emerging role of new technologies will force planners to adopt new assumptions around household and freight travel demand.

States departments of transportation will play a prominent role in addressing these shifting challenges. These offices must continue to put federal and own-source revenue to productive use, forge stronger connections with their regional and local partners, and be willing to accept comments from the public around where, how, and why to invest in specific projects and communities.

This research creates baseline data to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each state department of transportation in playing that modern role. While no state has the exact same starting point, all state DOTs have well-established capabilities they can use to plan and build a safer, more competitive, and more resilient transportation system. Aided by the right reforms at all levels of government, each agency is poised to deliver even more.

Downloads

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful for thoughtful comments from the tens of in-state and federal stakeholders who provided feedback on specific data and framing. The authors also thank the many individuals who provided thoughtful comments on an earlier draft, including Ann Bowman, Xavier de Souza Briggs, Joseph Kane, John Kincaid, Tom Kotarac, Michael Pagano, Robert Puentes, and Gian-Claudia Sciara. The authors also would like to thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Alec Friedhoff for data interactive coding, Carie Muscatello for her web and print design, and the rest of the Brookings Metro communications team for their support. All remaining errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Brookings Metro would like to thank the Kresge Foundation for their generous support of this analysis. Brookings Metro is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders who are both financial and intellectual partners of the Program.

-

Footnotes

- While often treated similarly to states and Washington, D.C. within USDOT policies, this paper does not include analysis of Puerto Rico out of respect for unique local governance within the Commonwealth.

- As one example, the Transportation Research Board maintains an enormous library of publications related to building staffing expertise (including this and this), in addition to offering trainings for different occupations.

- We use 2019 data in some instances, such as revenue, since it’s the last accounting year before COVID-19 impacted travel patterns.

- In some states, this data is limited to federally required performance measures that they do not connect to LRTP goals. Some states, though, have relatively strong performance reporting systems, even in the absence of performance measures defined in their LRTP. Hawaii, for example, required every state department to report on its goals, policies, and investment strategies when it passed Act 100 in 1999. Though it’s not measuring performance against long-range planning goals, Hawaii’s DOT now reports significant performance data in its yearly Act 100 report.

- “Federally funded” refers to those dollars distributed under title 23 U.S.C. and title 49 U.S.C Chapter 53.

- NHPP funding is determined after some set-asides for metropolitan planning and CMAQ programs. The program was set up to do three things for NHS roadways: 1) support condition and performance; 2) support new construction; and 3) connect highway investments using federal aid funds to achieving performance targets established by each state in an asset management plan.

- Federal law defines asset management as “a strategic and systematic process of operating, maintaining, and improving physical assets, with a focus on both engineering and economic analysis based upon quality information, to identify a structured sequence of maintenance, preservation, repair, rehabilitation, and replacement actions that will achieve and sustain a desired state of good repair over the lifecycle of the assets at minimum practicable cost.” USDOT put it more simply in an archived 2007 report: asset management principles require an organization to base decisions on information and get results.

- While not the same, TAMPs complement the reporting requirements under GASB 34, which include infrastructure quality assessments within a state’s annual financial report. However, this research does not assess the relationship between TAMPs and GASB 34 in detail. For more information, see GASB’s description.

- Federal law is more specific about collaboration with nonmetropolitan areas. State DOTs must document how they cooperate with such officials, submit it to the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, and accept comments from those officials on the process and provide a written explanation when proposed changes are rejected.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).