The Senate began a month-long recess on August 7, having confirmed five judges in 2015 compared to 26 at this point in President Bush’s seventh year in office and 11 in President Clinton’s. Then, as now, the party that controlled the Senate hoped in 14 months to regain control of the White House and judicial nominations.

The Senate in the final two years of both Clinton’s and Bush’s presidencies had fairly robust confirmation records, accounting for roughly a fifth of each president’s full eight years of confirmations. Senate majorities did not put the confirmation process on ice in order to make the maximum possible number of vacancies available for their party to try to fill if it prevailed in the presidential election. The Senate Judiciary Committee in 1999-2000 was chaired by Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and in 2007-08 by Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.). In those two year periods, both of these senators chaired the committee with knowledge about the federal courts, and an understanding that most federal judicial business has little ideological content, that civil disputes dominate federal dockets, and that filling judicial vacancies is important to allow litigants, such as small businesses, to get disputes resolved in a timely matter, given the statutory priority that district courts must give to criminal cases.

The Judiciary Committee is now chaired by Senator Charles Grassley (R-Ia). The 2015-16 Senate will likely not match its 1990-2000 and 2007-08 records. President Obama will probably appoint fewer circuit judges than did Clinton or Bush, and fewer district judges than Clinton. More important, unlike in those early periods, vacancies will likely increase.

This post compares the nomination-confirmation-nominee-less vacancy records at the August recess of these three president’s seventh year. Major findings:

- It is unreasonable to have expected the Senate to match the 26 confirmations during Bush’s first seven months of 2007 but not unreasonable to have expected one more circuit confirmation and five to seven more district confirmations.

- Some Senate Republicans are apparently using the Senate’s “blue slip” tradition to thwart confirmations by preventing nominations.

- Opposite party senators did the same thing during the Clinton and Bush administrations, but not to the same extent.

At the August recesses

Here is Senator Grassley’s explanation of why the Senate has only confirmed five judges so far this year: “Had we not confirmed…11 judicial nominees during the lame duck last year, we’d be roughly at the same pace we were for judicial confirmations this year compared to 2007.” Sixteen, though, is not “roughly” the same as 26; it’s a little more than half. More important, the proper metric for an effective confirmation process is not proportionality among congressional sessions.

The proper metric is filling vacancies pursuant to Article II of the Constitution, and on that measure, the Senate is hardly at the same pace as in 2007.

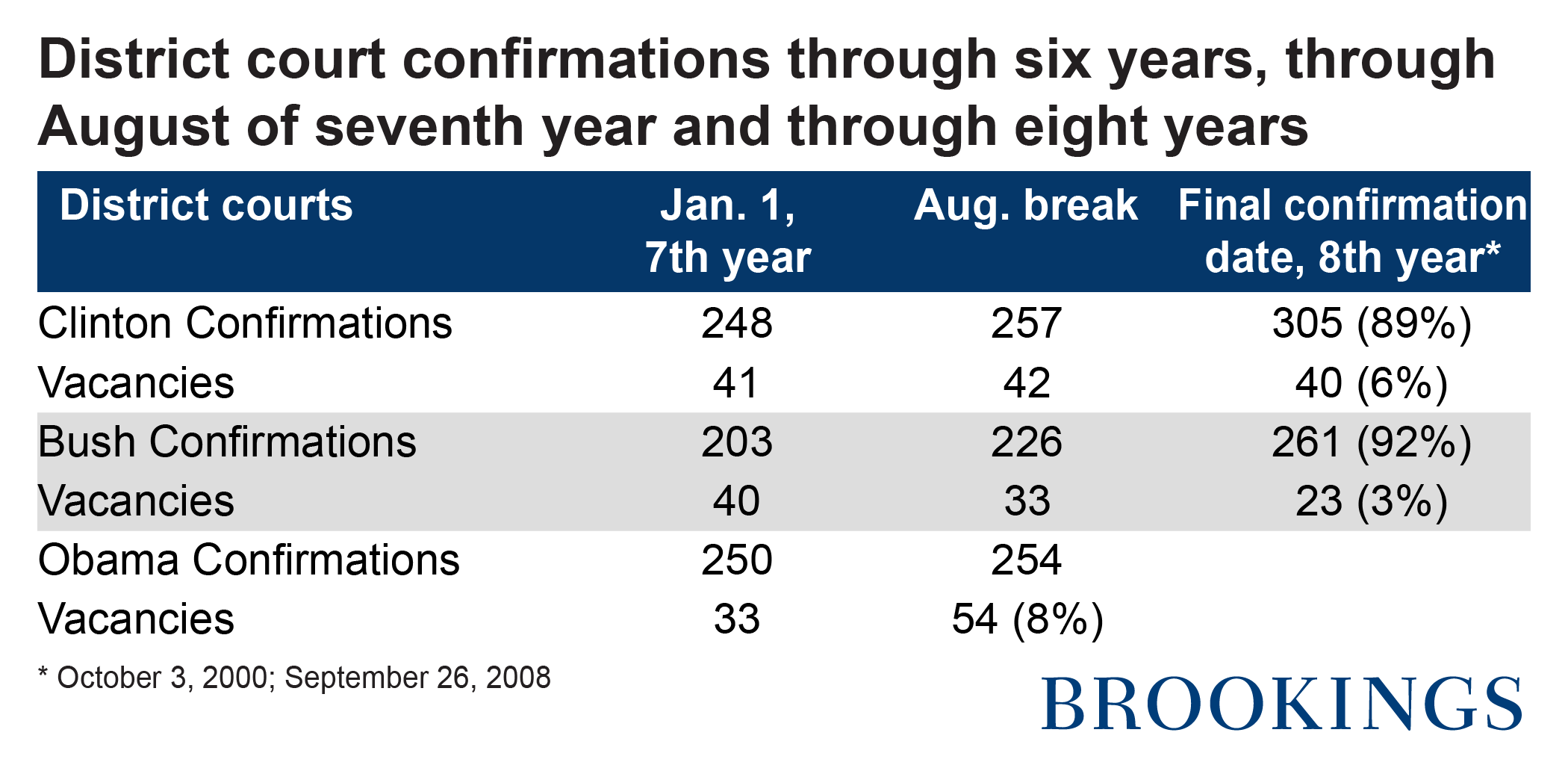

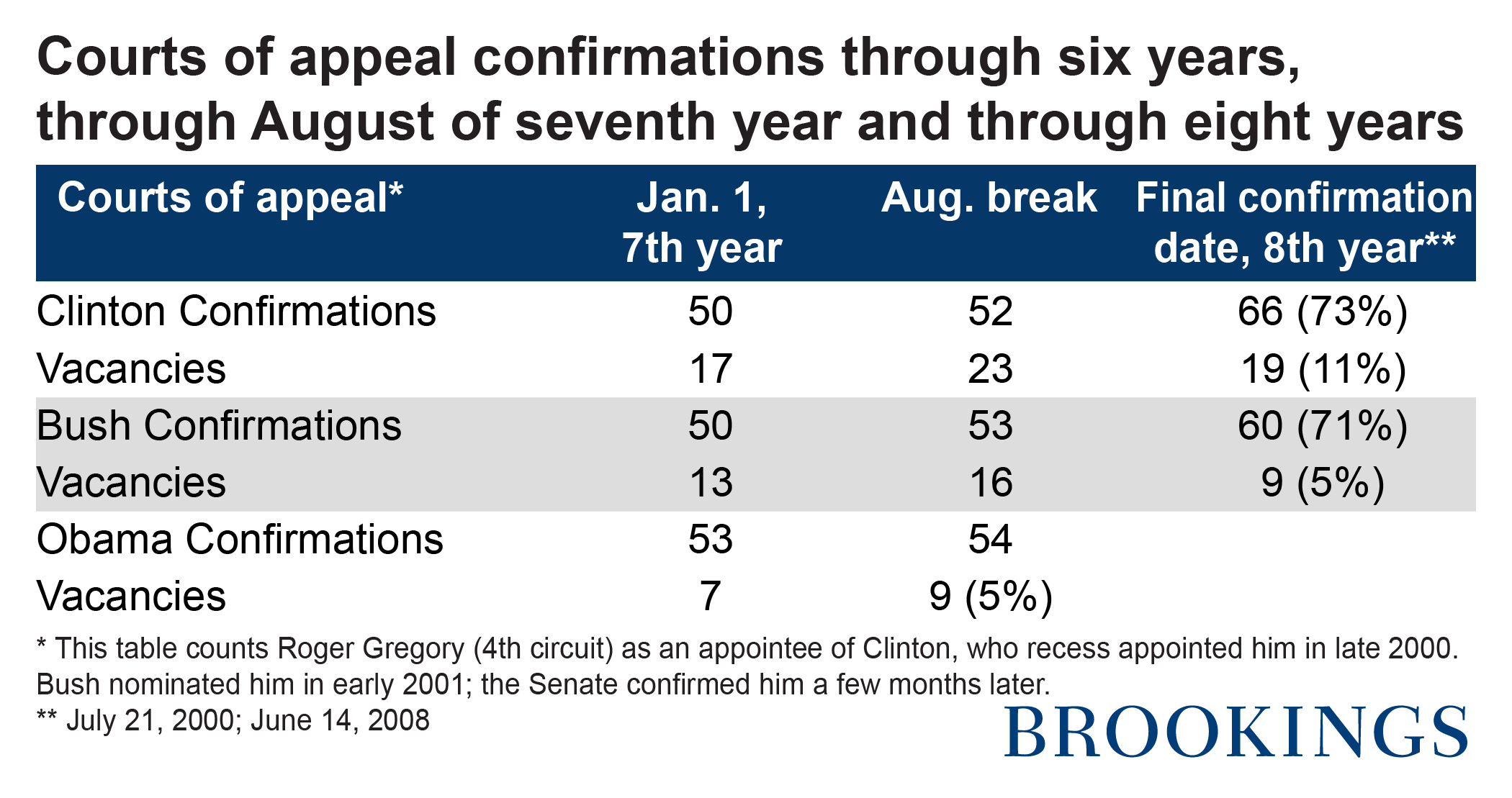

These tables provide, for district and then appellate courts, the number of Clinton, Bush, and Obama appointees at the start of their seventh year in office, at the start of the August break of that year, and the final number of appointees for Clinton and Bush (and their confirmation rates). The rows beneath the confirmation numbers show the number of vacancies at those respective points, and the final vacancy rate. (Clinton, for example, had appointed 248 district judges by January 1, 1999, and nine more by August 5, 1999. His final district confirmations, which came on October 3, 2000, brought his eight-year total to 305, 89 percent of his nominees. At that point there were 40 district vacancies, six percent of all 651 district judgeships.)

Under both Clinton and Bush, district vacancies declined between the start of their seventh years in office and the date of their final confirmation, by one for Clinton and by almost half for Bush (and both had final confirmation rates of about 90 percent). Those final vacancy figures got their start in the seven months prior to the seventh-year August break. In that period under Clinton, vacancies increased slightly, in part because of only nine district confirmations. By contrast, vacancies decreased from 40 to 33 under Bush, partly because of 23 district confirmations.

This year, 2015, opened with 33 district vacancies. But, due partly to only four district confirmations so far in 2015, vacancies have increased by almost two-thirds, to 54, justifying speculation that by late 2016, vacancies will be substantially higher than the 33 that began 2015.

The picture is murkier in the courts of appeals. Vacancies increased slightly in 1999-2000, but declined by four in 2007-08. In both instances, they were higher at the time of the August break, but these are small numbers.

Plausible expectations of additional confirmations prior to 2015’s August recess

Overall, instead of four district confirmations so far in 2015, given the number and dates of pending nominees one might reasonably have expected an additional five to seven confirmations. Instead of one circuit confirmation, one might reasonably have expected two, insofar as the only two circuit nominees in the Senate in 2015 had been originally nominated the same November day in 2014, and the Judiciary Committee approved both on voice votes. Why only one got confirmed is hard to explain as a matter of timing.

Of the 28 district nominees pending in 2015, four who had first been nominated in September, 2014 are the only four district confirmations so far in 2015—about seven months from initial nomination. Five more had first been nominated in November 2014 and two more in early February 2015. The Judiciary Committee reported out all seven on voice votes, most recently on July 9. None has been confirmed, but there was time to do so: confirmation on August 6, 2015, would have come from six to nine months after nomination.

Seventeen nominees were submitted in late February or after. Some of them might have been confirmed by August in earlier administrations, when the median time from district nomination to confirmation was three months (Clinton) or five months (Bush). Confirmation would have been highly unusual during the Obama administration, when the median time for confirmation has been over seven months. Almost no one would have expected confirmation of eleven June and July nominees.

The Senate has slated one of the five yet-to-be-confirmed November nominees for a September 8 floor vote. Upon confirmation, she will join the four confirmed last April and May. All are in states with at least one Republican senator. More about that later in this piece.

Nominee-less vacancies during the first seven months of 1999, 2007, and 2015

At present there are 54 district vacancies and 15 judgeships with incumbents who have publicly announced that they will create vacancies by leaving active status at some future date. (One more will be created if the Senate confirms the district judge whose nomination to the court of appeals has been pending since November.) Of those 70 current or projected vacancies, 45 have no nominees. Three quarters of them (34) are in states with at least one Republican senator.

The median time since those 34 vacancies’ announcements is 14 months, compared to five months for the 11 vacancies in two-Democratic senator states. Texas has seven of the nominee-less vacancies—14 percent of the state’s district judgeships. All the vacancies are at least a year old, with a median age of 19 months; one is over five years, another over two. In weighted filings, the four Texas districts rank second, eleventh, eighteenth, and twenty-second in the nation. Two vacancies in Kentucky have been nominee-less for a year-and-a-half and three-and-a-half years since their announcement, and two of the five current or announced vacancies in Alabama have been nominee less for over two years.

Today’s eight nominee-less circuit vacancies—all in states with at least one Republican senator— have a median age of almost two years (22 months). A vacancy in a Wisconsin seat (7th circuit) has been nominee-less for almost five years, and two vacancies in Texas have been without nominees for almost four years and for almost two. These imbalances have appeared earlier in the Obama administration, as documented here and here, and in previous administrations, as described below.

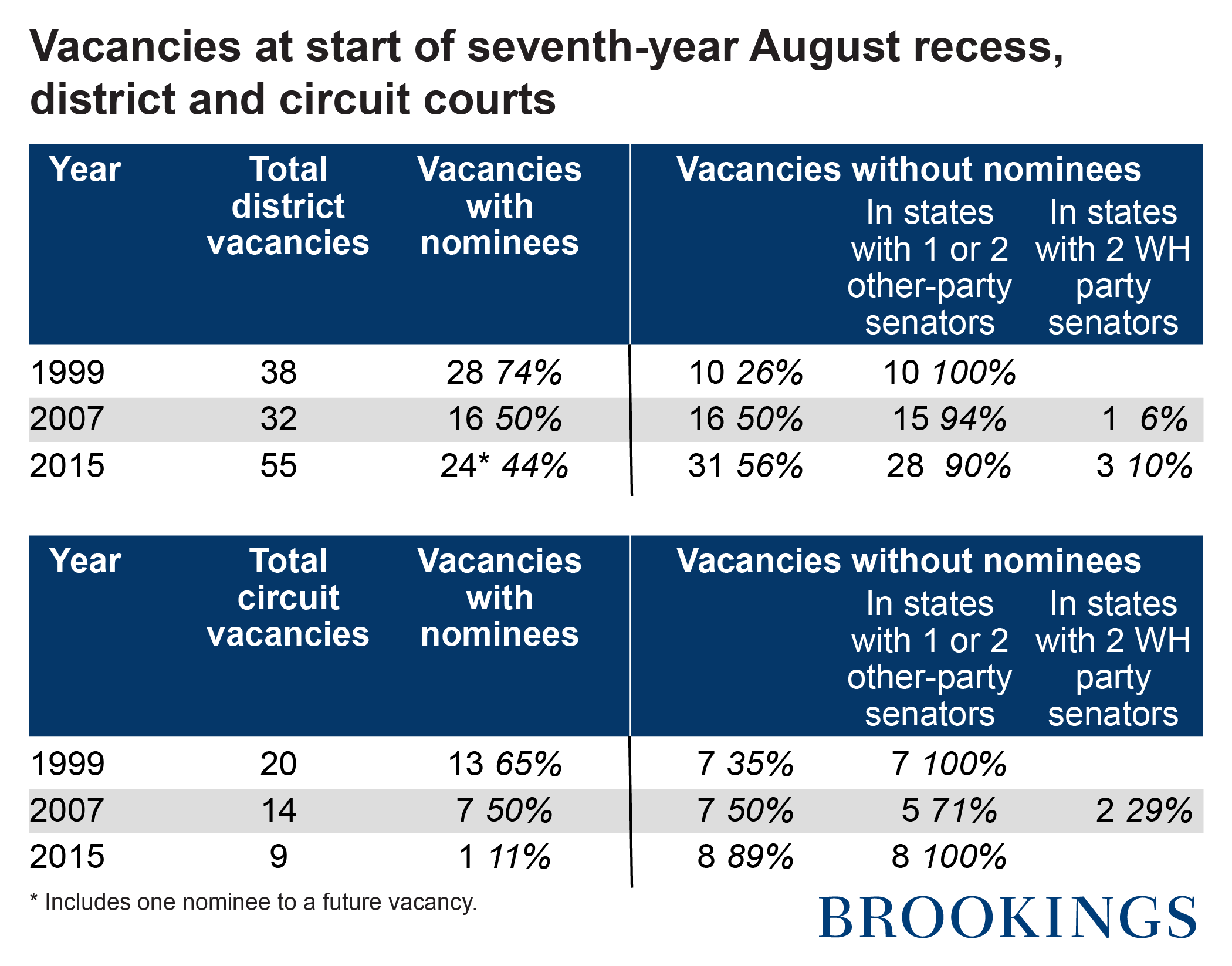

These tables put today’s situation in perspective by showing, for judgeships in courts with Senate delegations (excluding, e.g., those in the District of Columbia) total vacancies in place, those with nominees, and nominee-less vacancies according to the state’s Senate delegation. (Thus, for example, at this point in 2007, there were 32 district vacancies; 16 had nominees. Of the 16 that did not, 15 were in states with at least one Democratic senator.)

Nominee-less vacancies, at least at the August recesses:

- Have been growing as a proportion of all vacancies, from 26 percent of district vacancies in 1999 to 56 percent today.

- Have been disproportionately in courts with opposition-party senators: in 1999, as today, nominee-less vacancies were predominantly in states with Republican senators; in 2007, they were predominantly in states with Democratic senators. But the number of such vacancies has increased—from 10 in August 1999 to 31 today.

- Although not shown on the table, nominee-less vacancies have been growing in age. In 1999, nominee-less district vacancies in states with a Republican senator had a median age of 5.7 months, in states with two Democratic senators, 3.2 months. As noted above, today, the nominee-less vacancies in states with Republican senators have a median age of 14 months.

Assessing the age of nominee-less circuit vacancies is more difficult, given their smaller numbers and the presence of outliers due to multi-year standoffs in prior years, such as in North Carolina, Michigan, and California and Idaho.

What explains the concentration of nominee-less vacancies in courts with opposition-party senators?

Senate Grassley asserted in an April 15, 2015 press release that “[f]or nearly a century, the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee has brought nominees up for committee consideration only after both home-state senators have signed and returned what’s known as a ‘blue slip.’ This tradition is designed to encourage outstanding nominees and consensus between the White House and home-state senators.”

Although the record is somewhat less consistent than Grassley remembers (my colleague Sarah Binder explains, for example, that some home-state Democratic senators’ non-returned blue slips were not recognized during several of the years when Republicans controlled the Senate during the Bush administration), he describes quite accurately the Senate during Obama’s presidency, both under Democratic and now Republican control. In short, home-state senators of either party have a virtual veto over judicial nominations. Their disapproval of a nomination means it will go no where, making any White House reluctant to submit nominees to whom either senator will object. It happens occasionally but rarely.

Without access to Senator-White House negotiations, one cannot be certain as to why there are so many nominee-less vacancies today. Almost surely, different factors are playing out from state to state. Perhaps some Republican home-state senators are demanding a higher level of “consensus” than did other-party senators in previous decades (objecting more vigorously to White House-suggested candidates, or proposing nominees whom the White House is unlikely to accept). Perhaps some are refusing to endorse potential nominees simply to preserve vacancies for a Republican president to try to fill in 2017. Perhaps the White House, despite its weakened position in the process, has been resistant to compromise, although the administration has shown it can work with Republican senators to find mutually acceptable nominees. Of Obama’s 42 circuit appointees to courts with Senate delegations, 14 were in states with two Republican senators at the time of appointment and 10 in states with one.

Whatever the causes, the predominance of nominee-less vacancies in states with Republican senators (20 with two, 14 with one), and the comparative paucity of nominations in those states does not bode well for enough additional judicial appointments in 2015 and 2016 to reduce the number of vacancies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Confirming federal judges during the final two years of the Obama administration: Vacancies up, nominees down

August 18, 2015