It’s almost convention time and both political parties are having trouble getting it together. On the GOP side, high ranking Republicans—including former nominees of the party—are being slow and cautious in their embrace of Donald Trump. And on the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders, while running behind Hillary Clinton in delegates, is arguing that he is a stronger general election candidate against Trump. In the meantime, irate voters in both parties are wondering if, how, and why their votes could be overturned by these strange people called convention delegates.

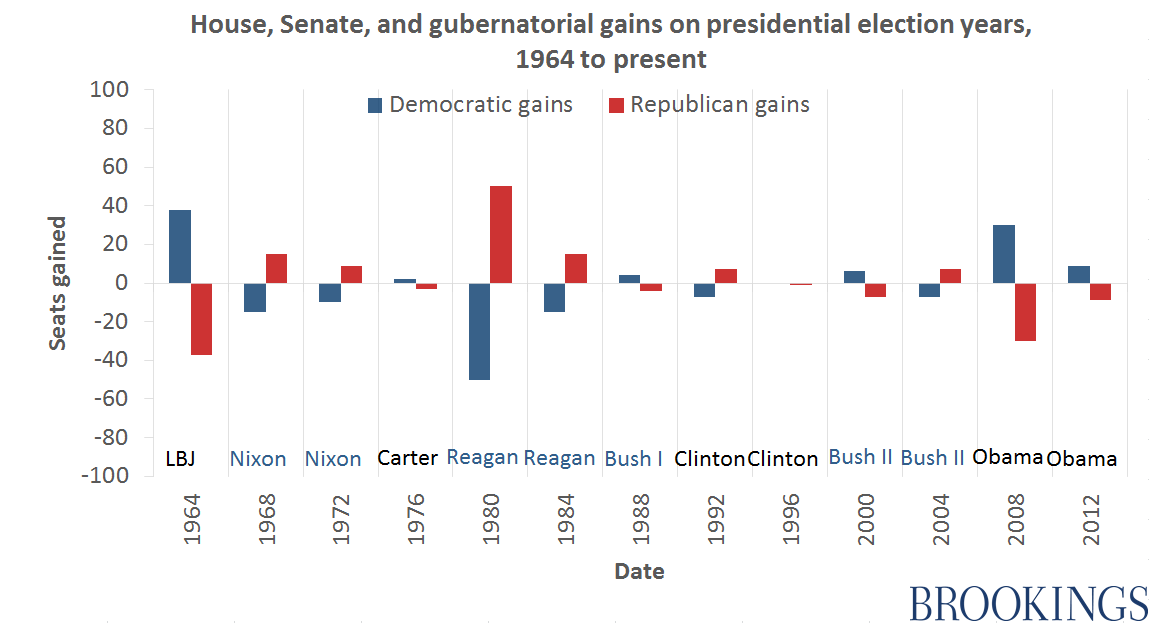

The reason is often lost in the public hoopla over the primaries. Nominations are party business and political parties exist not just for the top of the ticket but for the whole ticket—from president right down through dog-catcher. So when the elected officials who share the ticket and the party officials who work for the ticket think the top of the ticket is weak, they often find themselves at odds with voters in the primaries. Throughout history very popular presidential candidates have had “coat-tails,” meaning that the presidential candidate brought so many voters into their column that the other candidates got votes they didn’t even anticipate. And, of course, the opposite happens as well. Very unpopular presidential candidates often cause down-ballot candidates to lose. The following chart illustrates the point.

As we can see, unpopular presidential candidates, whether challengers or incumbents, can inflict a lot of damage on other members of their party. In 1964, the Republican nominee, Senator Barry Goldwater, cost his party a total of 38 seats in Congress (House and Senate). In 1980, the unpopular incumbent, President Jimmy Carter, cost his party a whopping 50 congressional and gubernatorial elections and 28 years later, another unpopular president, George W. Bush, cost his party 30 major seats. Of course there are some years when the top of the ticket is less controversial and thus has little effect on other races. This year, however, doesn’t look to be one of them.

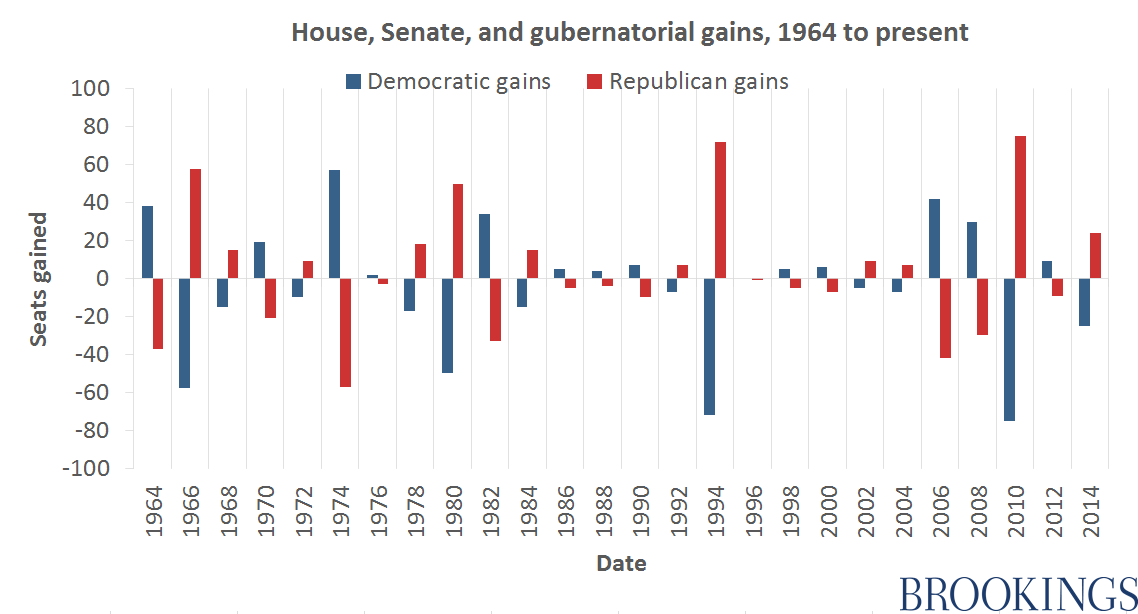

The damage an unpopular candidate does in a presidential election year does, sometimes, get undone in the midterm elections. As the following chart shows, in 1966, Republicans gained back seats they had lost in 1964 plus some. Ditto for Democrats in 1974, Republicans in 1994, and Republicans in 2010— just to name a few occasions

Nonetheless, political parties take elections one at a time and no one likes to take a chance on the top of the ticket, which is why both parties have been slow in coming together in 2016.

Elaine C. Kamarck is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of

Primary Politics: Everything You Need to Know about How America Nominates Its Presidential Candidates. She is a superdelegate to the Democratic convention.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Coat-tails and down-ballot worries for the 2016 election

May 19, 2016