More On

The members of China’s Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee were revealed at the conclusion of the First Plenum of the 19th Central Committee on October 25, 2017. Below are background profiles for all 25 members of the Politburo, as well as more detailed biographies for the 7 Politburo members who also hold a seat on the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee.

19th Politburo Standing Committee

19th Politburo

Note: All members of the Politburo Standing Committee (above) also hold a seat on the Politburo.

Profiles of the 19th Politburo

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Xi Jinping 习近平

- Born 1953

- General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (2012–present)

- President of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (2013–present)

- Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) (2012–present)

- Chairman of the National Security Committee (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Foreign Affairs and National Security (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Taiwan Affairs (2012–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Leading Group for Network Security and Information Technology (2014–present)

- Head of the CMC Central Leading Group for Deepening Reforms of National Defense and the Military (2014–present)

- Commander in Chief of the Joint Operations Command Center of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) (2016–present)

- Chairman of the Central Military and Civilian Integration Development Committee (2017–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2007–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Xi Jinping was born on June 15, 1953, in Beijing. His ancestral home is Fuping County, Shaanxi Province. Xi was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Yanchuan County, Shaanxi (1969–75).1 He joined the CCP in 1974. He received his undergraduate education in chemical engineering from Tsinghua University in Beijing (1975–79) and later graduated with a doctoral degree in law (Marxism) from the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at Tsinghua University (via part-time studies, 1998–2002).

Early in his career (1979–82) he served as a personal secretary (mishu) to Geng Biao, then minister of defense. Subsequently, Xi served as deputy secretary and then secretary of Zhengding County, Hebei Province (1982–85), and thereafter in Fujian Province as executive vice-mayor of Xiamen City (1985–88), party secretary of Ningde County (1988–90), party secretary of Fuzhou City (1990–96), deputy party secretary of Fujian Province (1996–99), governor of Fujian Province (1999–2002), governor of Zhejiang Province (2002), and party secretary of Zhejiang Province (2002–07). In March 2007, Xi was appointed party secretary of Shanghai. Seven months later, he was transferred to Beijing to serve as a Politburo Standing Committee member (2007–present) and executive secretary of the Secretariat of the CCP Central Committee (2007–12). In March 2008, he was elected PRC vice-president (2008–13). Xi was in charge of preparations for both the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing and the celebrations commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the PRC in 2009. He also served as president of the Central Party School (2007–12), the most important venue for training officials and ideological/policy research in the CCP. He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Xi is a princeling, the son of Xi Zhongxun, a former Politburo member and vice-premier who was one of the architects of China’s Special Economic Zones in the early 1980s.2 Xi Jinping is widely considered to be a protégé of both former PRC president Jiang Zemin and former PRC vice-president Zeng Qinghong. Xi’s first marriage produced no children. His ex-wife, Ke Lingling, is the daughter of Ke Hua, former PRC ambassador to the United Kingdom, where Ke Lingling now lives. Xi’s current wife, from his second marriage, is Peng Liyuan, a famous Chinese folksinger who, until recently, served in the PLA at the rank of major general. Their only daughter, Xi Mingze, received her undergraduate degree in psychology from Harvard University (2010–14) and is now a graduate student in the same field at a university in China.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Xi will surely be reelected as general secretary of the CCP and chairman of the CMC at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, and then as president of the PRC at the 13th National People’s Congress in March 2018. He will likely retain most or all of his current leadership positions during his second five-year term as China’s top leader. In the course of his first term, Xi has proven himself to be China’s strongest leader since Deng Xiaoping. Of the many noteworthy developments from this period, the following three efforts stand out:

Anti-Graft Campaign – With the support of his principal political ally in the PSC, “anticorruption czar” Wang Qishan, Xi launched a remarkably bold national anti-graft campaign that resulted in the purges of not only retired heavyweight leaders such as former PSC member Zhou Yongkang, but also about 10 percent of the members of the 18th Central Committee, including Politburo member Sun Zhengcai. To a certain extent, the overriding objective of his anti-corruption campaign has been to restore faith in a ruling party that had lost the trust of the Chinese public in the wake of notorious cases like the Bo Xilai scandal and the Ling Jihua incident.3

Military Reform – Xi achieved a milestone victory in restructuring the PLA, officially referred to as “military reform” (军队改革). His efforts have centered on marginalizing the four PLA general departments that had undermined the authority of the civilian-led CMC; transforming China’s military operations from a Russian-style, army-centric system toward what analysts call a “Western-style joint command”; and swiftly promoting “young guards” to top positions in the officer corps.

Proactive Foreign Policy – Xi’s “proactive” approach to foreign policy (奋发有为) marks a significant departure from Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of “keeping a low profile” (韬光养晦). His efforts have sought to showcase China’s rapid rise on the world stage under his leadership, including through the launch of the “Belt and Road Initiative” and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), concerted attempts to seek a “new model of great power relations” with the United States, and China’s deepening engagement in international institutions and venues, such as the Davos World Economic Forum.

On other policy issues, however, Xi has exhibited paradoxical preferences and tendencies. For example, the objective of his economic policy, as articulated at the third plenum of the 18th Central Committee in 2013, has been to make the private sector the decisive driver of the Chinese economy. Yet, Xi continues to favor China’s industrial policy and has called for making flagship state-owned enterprises “bigger and stronger.”

His attitude toward public intellectuals has proven similarly ambivalent. Whereas Xi has promoted Chinese think tanks, which are mostly staffed with academics, his politically conservative approach to governance—particularly his reliance on ideological oversight and media censorship—has left him at loggerheads with many of the country’s intellectuals. Likewise, the fourth plenum of the 18th Party Central Committee, which was held in the fall of 2014, was devoted to China’s legal reform. This was the first time in CCP history that a plenum concentrated on law, and it seems that Xi, more than any previous top leader, is interested in having his legacy center on the development of rule of law and the judiciary in China. But critics often point to the arrests and harassment of human rights lawyers in China as examples that the rule of law in China has actually regressed—not advanced—under Xi’s leadership.

Some of this cognitive dissonance may be temporary compromise as Xi positions himself to gain broad support from various forces in the country. If Xi aspires to be a truly great and transformative Chinese leader, sooner or later he must present a clear and coherent vision for the country while also respecting the political rules and norms that have laid the groundwork for China’s economic and political rise. The outcomes of the 19th Party Congress, particularly the new leadership lineup and revised ideological and policy agendas, will reveal how Xi plans to draw upon the political capital he accumulated during his first term and will offer important clues on whether he intends to promote or undermine political institutionalization.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- For more information on Xi’s family background and his early life experiences, see Liang Jian 梁剑, New Biography of Xi Jinping [习近平新传] (New York: Mirror Books, 2012), and Wu Ming 吴鸣, Biography of Xi Jinping [习近平传] (Hong Kong: 文化艺术出版社, 2008).

- For a detailed discussion of these cases, see Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), pp. 1–5, 23–24.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Li Keqiang 李克强

- Born 1955

- Premier of the State Council (2013–present)

- Vice-Chairman of the National Security Committee (2013–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work (2013–present)

- Vice-Chairman of the Central Military and Civilian Integration Development Committee (2017–present)

- Chairman of the Committee on Organizational Structure of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

- Chairman of the National Defense Mobilization Committee (2013–present)

- Director of the State Energy Commission (2013–present)

- Head of the National Leading Group for Climate Change and for Energy Conservation and Reduction of Pollution Discharge (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Rejuvenating the Northeast Region and Other Old Industrial Bases (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Western Regional Development (2013–present)

- Head of the State Council Three Gorges Project Construction Committee (2008–present)

- Head of the State Council South-to-North Water Diversion Project Construction Committee (2008–present)

- Head of the State Council Leading Group for Deepening Medical and Health System Reform (2008–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (2007–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (1997–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li Keqiang was born on July 1, 1955, in Dingyuan County, Anhui Province. Li joined the CCP in 1976. He was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Fengyang County, Anhui (1974–76).1 He served as party secretary of a production brigade in the county (1976–78). Li received both a bachelor’s degree in law (1982) and a doctoral degree in economics (via part-time studies, 1994) from Peking University. As an undergraduate majoring in law, Li studied under Professor Gong Xiangrui, a well-known, British-educated expert on Western political and administrative systems. Li and his classmates translated important legal works from English into Chinese, including Lord Denning’s The Due Process of Law and A History of the British Constitution.2 As a Ph.D. student in economics, Li studied under Li Yining, a well-known economist whose theories have been instrumental in guiding China’s state-owned enterprise reform.

Li advanced his early career mainly through the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL), serving as secretary of the CCYL Committee at Peking University (1982–83). Within the Secretariat of the CCYL Central Committee, he served sequentially as alternate member (1983–85), secretary (1985–93), and first secretary (1993–98). In 1998, Li was transferred to Henan Province, where he served as governor (1998–2003) and, concurrently, deputy party secretary (1998–2002) and then party secretary (2002–04). He then served as party secretary of Liaoning Province (2004–07). In October 2007, he was promoted to be a Politburo Standing Committee member (2007–present) and, shortly thereafter, served as executive vice-premier of the State Council (2008–13). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Li comes from a mid-level official family—his father, Li Fengsan, was a county-level cadre in Fengyang County, Anhui.3 Li’s wife, Cheng Hong, is currently a professor of English language and literature at Capital University of Economics and Business in Beijing. Li’s father-in-law, Cheng Jinrui, served as deputy secretary of the Henan Provincial CCYL Committee. The couple has one daughter, who received her undergraduate degree from Peking University and later studied in the United States, according to some unverified sources.

Li is widely considered to be a protégé of Hu Jintao. Li began working in the CCYL Central Committee at the end of 1982, at exactly the same time that Hu Jintao became secretary of the CCYL. Li Keqiang worked closely with Hu, assisting him in convening the Sixth National Conference of the All-China Youth Federation in August 1983. Three months later, after being nominated by Hu, Li was promoted to alternate member of the CCYL Secretariat. When Hu was made first secretary of the CCYL in 1985, Li became a full member of the Secretariat. For most of the Hu era, Li was seen as a possible successor to his mentor.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Compared with his two predecessors, Premier Zhu Rongji and Premier Wen Jiabao, Li Keqiang’s power and authority have been noticeably limited—even on economic policy. Observers argue that Premier Li has been marginalized, as Xi has taken over all of the top posts in economic affairs, which traditionally fell within the purview of the premier.4 Nevertheless, over the past five years, Premier Li has promoted hot-button policy issues, such as township-centered urbanization (城镇化), affordable housing, employment, food security, public health care, clean energy technology, and the reduction of bureaucratic barriers for private sector development. In particular, Li has frequently called for “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” (大众创业, 万众创新), which apparently has contributed to the country’s technological development over the past few years, as evidenced by the vitality of China’s e-commerce and e-payment systems.

Li was certain to remain on the Politburo Standing Committee after the 19th Party Congress. He will also likely retain his premiership for a second term, beginning in March 2018. At a time when Xi enjoys tremendous individual power, Li can be viewed as a balancing force for preserving collective leadership within the political establishment.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- Li Meng, “Li Keqiang and the class of ’77 at the Department of Law at Peking University” [Li Keqiang suozai de beida falüxi 77 ji], Democracy and Law [Minzhu yu fazhi], October 26, 2009.

- For more information about Li Keqiang’s family background and his early experiences, see Hong Qing 洪清, “He will be China’s Top Manager: The Biography of Li Keqiang” [他将是中国大管家—李克强传] (New York: Mirror Books, 2010).

- Jeremy Page, Bob Davis, and Lingling Wei, “Xi Weakens Role of Beijing’s No. 2,” Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2013.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Li Zhanshu 栗战书

- Born 1950

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (2017–present)

- Director of the General Office of the CCP Central Committee (2012–present)

- Secretary of the Central Work Committee for Organs of the CCP Central Committee (2012–present)

- Director of the Office of the National Security Committee (2013–present)

- Head of the Central Confidential Commission of the CCP Central Committee (2013–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Secretariat member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–2017)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li Zhanshu was born on August 30, 1950, in Pingshan County, Hebei Province. Li was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in his native county (1968–72).1 He joined the CCP in 1975. He studied at the Shijiazhuang Institute of Commerce in Shijiazhuang City, Hebei (1971–72), and received an undergraduate education in politics from Hebei Normal University in Shijiazhuang City (via part-time studies and night school, 1980–83). He also attended the graduate program in business economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1996–98) and received an EMBA from the Harbin Institute of Technology in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province (2005–06), both on a part-time basis.

Li began his political career as a clerk and later served as deputy director in the office of the commerce bureau of the Shijiazhuang prefecture government in Hebei (1972–76). He moved on to become a clerk and division head of the information division of the general office of the CCP Committee of Shijiazhuang Prefecture (1976–83). He was then promoted to party secretary of Wuji County, Hebei (1983–85). He next served as deputy party secretary and head of Shijiazhuang Prefecture (1985-86) and secretary of the Hebei Provincial Chinese Communist Youth League Committee (1986–90), during which time he attended a six-month program on CCP theoretical work at the Central Party School (1988). He served as deputy party secretary and head of Chengde Prefecture, Hebei (1990–93), and secretary-general (chief of staff) of the CCP Provincial Committee of Hebei (1993–97), during which time he studied economics in a correspondence program at the Central Party School (1992–94). He later served as deputy director of the Rural Work Office of the CCP Provincial Committee of Hebei (1997–98). In 1998, he was transferred to Shaanxi Province, where he served as deputy director of the Rural Work Office of the CCP Provincial Committee of Shaanxi (1998–2000), director of the Organization Department (2000–02) of the CCP Provincial Committee of Shaanxi, and party secretary of Xi’an City (2002–03). He also served as deputy party secretary of Shaanxi Province (2002–03). In 2003, Li was transferred to Heilongjiang Province, where he served as deputy party secretary (2003–10), vice-governor (2004–07), and then governor (2008–10). In 2010, he was transferred to Guizhou Province, where he served as party secretary (2010–12).

On the eve of the 18th Party Congress in September 2012, at the nomination of Xi Jinping, Li was appointed director of the General Office of the CCP Central Committee, replacing Ling Jihua, a top aide to then-general secretary Hu Jintao. Li was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Li comes from a family of Chinese communist veterans. It has been reported that 27 members of Li Zhanshu’s extended family joined the CCP during the communist revolution.2 His great-uncle, Li Zaiwen, joined the CCP in 1927 while a student at Peking University and later served as secretary of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and vice-governor of Shandong. Li Zaiwen was persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and died under harsh treatment in 1967. He was rehabilitated and named a revolutionary martyr in 1979.3 Li Zhanshu’s father, Li Zhengxiu, and his uncle, Li Zhengtong, both joined the CCP in the 1930s. Li Zhengtong died on a battlefield during the civil war in 1949 at the age of 26.

Li Zhanshu is one of Xi Jinping’s most trusted long-time friends. Their friendship began over three decades ago, when Xi served as deputy party secretary and then party secretary of Zhengding County in Hebei from 1982 to 1985. Li Zhanshu served as party secretary of Wuji County in the same province during roughly the same period.4 Both counties belong to Shijiazhuang Prefecture and are close geographically, so Xi and Li developed a good working relationship. Li is also widely seen as a member of the “Shaanxi Gang,” Xi’s most important power base.5

In addition to their longtime friendship and similar family backgrounds, some of Li’s work experiences are particularly valuable for Xi. First, Li has served as a provincial leader in many parts of the country: in Hebei as secretary-general of the provincial party committee, in Shaanxi as deputy party secretary, in Heilongjiang as governor, and in Guizhou as party secretary. These connections to the northern, northeastern, northwestern, and southwestern regions of the country could help Xi mobilize broad regional support. Second, Li’s CCYL leadership background could help Xi reconcile factional tensions in the CCP’s top leadership and, thus, assist with his coalition-building efforts.6

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Not only is Li Zhanshu a leading candidate for the 19th Politburo Standing Committee; he is also a Wang Qishan-like figure who offers Xi Jinping advantages on numerous fronts. He may serve as chairman of the National People’s Congress, which would rank him third in the leadership hierarchy, behind Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang.

As Xi’s chief of staff for the past five years, Li has been beside his boss at almost all pivotal meetings, including the Xi-Obama summit at Sunnylands in 2013, Xi’s meeting with Ma Ying-jeou in Singapore in 2015, and the Xi-Trump summit at Mar-a-Lago in 2017. As Xi Jinping’s personal emissary, Li Zhanshu has also visited Moscow to meet President Vladimir Putin twice (in March 2015 and April 2017).

When he was governor of Heilongjiang almost ten years ago, Li told a Chinese reporter for CCTV that he expected to retire in a few years.7 It was Xi Jinping who carried Li forward. Unsurprisingly, Li has made a concerted effort to help consolidate Xi Jinping’s power and “core” status within the CCP leadership. Li, who is known for his expertise on rural development, has also worked extensively across various other domains, including personnel, ideology, party discipline, security, and foreign affairs. Whereas Wang Qishan was a history major in college and often analyzes the present and future through the lens of historical precedent, Li Zhanshu is fond of poetry and literature. It remains to be seen whether this difference will have any impact on the governance of the country as Li assumes a central role in Chinese politics.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- Zi Yang, “Meet China’s Emerging Number 2: A biography of Li Zhanshu, the right-hand man to Xi Jinping,” The Diplomat, May 6, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/05/meet-chinas-emerging-number-2.

- Si Fan, “Portrait of the 18th Party Congress Leader Li Zhanshu: A Seasoned Chief of Staff” [十八大人物之栗战书: 多重历练的“大内总管”], Dagong Daily, September 3, 2012, http://www.takungpao.com/mainland/content/2012-09/03/content_1036483.htm.

- Xiang Jiangyu, Xi Jinping’s Team [习近平的团队] (New York: Mirror Books, 2013).

- Cheng Li, “Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 1: The Shaanxi Gang),” China Leadership Monitor, No. 43, Spring 2014.

- Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), pp. 216–17.

- “Interview with Heilongjiang Governor Li Zhanshu,” CCTV Online, March 27, 2008, http://cctvenchiridion.cctv.com/special/C20768/20080327/103474.shtml.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Wang Yang 汪洋

- Born 1955

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2017–present)

- Vice Premier of the State Council (2013–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2007–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Wang Yang was born on March 12, 1955, in Suzhou County, Anhui Province. He joined the CCP in 1975. He attended a program in political economy at the Central Party School (CPS) in Beijing (1979–80), received a bachelor’s degree in public administration from the CPS (via correspondence courses, 1989–92), and received a master’s in management science from the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei City, Anhui (via part-time studies, 1993–95). Wang also twice pursued mid-career cadre training at the CPS (in 1997 and 2001).

Wang began working as a manual laborer and then served as manager in a food factory in Suxian County, Anhui (1972–76). He advanced his career first through the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL), serving as CCYL deputy secretary of Suxian County (1981–82), propaganda director of the CCYL Anhui Provincial Committee (1982–83), and deputy secretary of the CCYL Anhui Provincial Committee (1983–84). He served as deputy director and then director of the Anhui Provincial Sports Commission (1984–88); as mayor and deputy party secretary of Tongling City, Anhui (1988–92); and, concurrently, as chairman of Anhui Province’s Economic Planning Commission and assistant governor of the province (1992–93).

At the age of 38, Wang was appointed executive vice-governor of Anhui Province (1993–99). He was then transferred to the central government, where he served as vice-minister of the State Development Planning Commission (SDPC) (1999–2003) and then as deputy secretary-general (chief of staff) of the State Council (2003–05). He next served as party secretary of Chongqing (2005–07) and then Guangdong (2007–12). Wang was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Wang was born into a family of humble means.1 His father died when he was a young boy. As the eldest child, he began working at the age of 17 to help his mother support the family.2 Wang is widely considered a protégé of Hu Jintao, with whom he developed strong patron-client ties in the early 1980s, when Hu was head of the CCYL and Wang was deputy secretary of the Anhui Provincial CCYL Committee. Some PRC journalists have reported that Deng Xiaoping “discovered” Wang Yang in 1992 when Deng visited Anhui and met the 37-year-old Wang, who was then mayor of Tongling City. Deng was quoted as saying: “Wang Yang is an exceptional talent.”3

Wang’s wife, Zhu Mali, was the daughter of a local leader. Her father, Zhu Jiayuan, was deputy head of Shuxian Prefecture. Wang and his wife have one daughter, Wang Xisha, a graduate of Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management and of Tufts University, where she received a master’s degree. She previously served as a senior manager at Deutsche Bank in Hong Kong. Her husband, Zhang Xinliang (Nicholas Zhang), is the grandson of former minister of defense Zhang Aiping. Zhang Xinliang received his bachelor’s degree in international economics from Georgetown University. Zhang has worked for a number of foreign investment banks, including UBS, Goldman Sachs, and Soros Fund Management.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Wang possesses broad leadership experience in both the central government (the SDPC and State Council) and in major provincial and municipal posts (in inland Chongqing and coastal Guangdong). Given his relatively young age, Wang is the only one among the four vice-premiers in the State Council who need not retire from the position after the 2018 National People’s Congress. As a two-term Politburo member, Wang was seen as a strong candidate for the current Politburo Standing Committee. He may also assume the position of either executive vice-premier of the State Council or chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

Wang’s primary policy interests include transforming China’s economy from being driven by exports and reliance on cheap labor to an innovation-led model powered by domestic consumption; strengthening the private sector and foreign trade; promoting intra-party democracy and village elections; increasing media transparency; and implementing bolder political reforms.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- According to one unverified source, Wang’s father served as party secretary of a food company in Shuxian County.

- For more information about Wang Yang’s family background and his early experiences, see Du Zijia 窦梓稼, Biography of Wang Yang: That “Wolf” in China’s Political Arena [汪洋传: 中国政坛那匹 “狼 ”] (New York: Mirror Books, 2009), and Wang Yaohua 王耀华, Competition among Provincial Chiefs [诸侯争锋] (New York: Mirror Books, 2009), pp. 13–58. For Wang’s recent views on and efforts toward political and economic reforms in Guangdong, see Cheng Li, “Hu’s Southern Expedition: Changing Leadership in Guangdong,” China Leadership Monitor, No. 24, Spring 2008.

- Earth Week [大地周刊], No. 23, 2009; also see http://news.hexun.vnet.cn/2010-01-02/122228741.html.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Wang Huning 王沪宁

- Born 1955

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2017–present)

- Executive Secretary of the Secretariat of the CCP Central Committee (2017–present)

- Director of the Central Policy Research Center of the CCP Central Committee (2002–present)

- Secretary-General (Chief of Staff) and Director of the General Office of the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms (2013–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Wang Huning was born on October 6, 1955, in Shanghai. His ancestral/family home is in Laizhou County, Shandong Province. Wang joined the CCP in 1984. He studied French language as part of the Cadre Training Class at Shanghai Normal University in Shanghai (1972–77) and attended the graduate program in international politics at Fudan University in Shanghai (1978–81), where he also received a master’s degree in law (1981). He has been a visiting scholar at the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan, and the University of California at Berkeley (1988–89). He speaks French fluently.

Wang began his career as a cadre in the Publication Bureau of the Shanghai municipal government (1977–78). After receiving his master’s, he stayed on at Fudan University and served as an instructor, associate professor, and professor (1981–89), then as chairman of the Department of International Politics (1989–94), and finally as dean of the law school (1994–95).

Wang moved to Beijing in 1995 and served as head of the Political Affairs Division of the Central Policy Research Center (CPRC) of the CCP Central Committee (1995–98), followed by a position as deputy director of the CPRC (1998–2002). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Wang Huning is one of only a few leaders unanimously favored by the three most recent party bosses: Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping. Accordingly, Wang has earned the nickname “chief advisor of Zhongnanhai” (中南海首席智囊) and “China’s Kissinger.”1 Wang is thought to have served as an informal conduit between Jiang and Hu during Hu’s leadership. In the late 1980s, he established his patron-mentor relationship with Jiang Zemin and Zeng Qinghong, who were then top leaders in Shanghai, and thus he earned membership in the “Shanghai Gang.” Since Hu succeeded Jiang as general secretary of the CCP and president of the PRC in 2002 and 2003, Wang became a top aide to Hu and frequently accompanied him on domestic and international trips. Similarly, like Xi’s chief of staff Li Zhanshu, Wang Huning has often been beside Xi Jinping throughout his first term, taking part in almost all important trips and meetings, both domestically and internationally.

Wang’s ex-wife, Zhou Qi, is the daughter of a vice-minister-ranked leader who worked in state security and intelligence. Wang and Zhou were classmates in the master’s program at Fudan, and Zhou later received a Ph.D. in political science from Johns Hopkins University’s Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). She worked as a research fellow in the Institute of American Studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) for many years. She currently serves as executive director of the National Strategy Institute at Tsinghua University. The couple divorced in 1996 and do not have any children. Wang recently was remarried to a nurse in Zhongnanhai, and the couple has one child.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Wang is believed to have been a principal drafter of the theory of “three represents” that was expounded by Jiang.2 In his early career as a political science professor and law school dean at Fudan University in the 1980s, Wang published many books and was considered a leading scholar advocating neo-authoritarianism.3 Wang Huning recently republished a 1986 article in which he argued that “public security, prosecutors, and the court merging into one” was one of the main reasons for prevalent human rights violations such as torture and vandalism during the Cultural Revolution. He stated unambiguously that “the Cultural Revolution could happen only in a country without an independent judicial system.”4 Wang’s primary policy concerns may include promoting rule of law and political reforms.

The fact that Wang Huning had served almost exclusively as an adviser to top leaders (Jiang, Hu, and Xi) seemed to put him at a slight disadvantage when it came to winning a seat on the PSC. Over the past three decades, virtually all PSC members have served either in provincial or municipal leadership roles or as governmental leaders in the State Council, and most have served in more than two province-level administrations. But as a leader who has advanced his political and professional career primarily through think tank work, Wang Huning represents a new channel for elite recruitment. His rise to the top leadership is very much in line with Xi Jinping’s recent call for building new think tanks with Chinese characteristics that will help further China’s strategic mission and integrate the Western-style “revolving door” into China’s political system.5

In addition to obtaining a seat on the 19th Politburo Standing Committee, Wang may take over Liu Yunshan’s positions as executive secretary of the Secretariat and president of the Central Party School. Wang’s expertise in law and public policy could be enormously helpful for advancing a new slate of priorities during Xi’s second term.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- Pratik Jakhar, “China party congress: The rising stars of China’s Communist Party,” BBC Online, October 8, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-41322178.

- In contrast to the Marxist notion that the Communist Party should be the “vanguard of the working class,” Jiang’s theory claims that the CCP should represent the “developmental needs of the advanced forces of production,” the “forward direction of advanced culture,” and the “fundamental interests of the majority of the Chinese people.”

- For the early career of Wang Huning and his writings, see “Hu Jintao’s two mysterious right-hand men: Ling Jihua and Wang Huning” [胡锦涛身边的神秘左右手:令计划和王沪宁], Social Perspective [社会聚焦], posted on April 7, 2010, http://bbs.tiexue.net/post2_4181927_1.html.

- Wang Huning, “Reflections on the Cultural Revolution and the Reform of China’s Political System” [文革反思与政治改 革], Readers’ Digest [文摘], February 23, 2012, originally appeared in The World Economic Herald [世界经济导报], May 1986.

- Cheng Li and Lucy Xu, “Chinese Think Tanks: A New ‘Revolving Door’ for Elite Recruitment,” China-US Focus, January 26, 2017, http://www.chinausfocus.com/political-social-development/chinese-think-tanks-a-new-revolving-door-for-elite-recruitment.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Zhao Leji 赵乐际

- Born 1957

- Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (2017–present)

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (2017–present)

- Director of the Central Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee (2012–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Party Building Work (2012–present)

- Deputy Head of the Central Leading Group for Inspection Work (2012–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Zhao Leji was born on March 8, 1957, in Xining City, Qinghai Province. His ancestral home is Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, and his parents served as cadres who moved from Xi’an to support frontier work in economically disadvantaged Qinghai. Zhao joined the CCP in 1975. He was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Qinghai’s Guide County during the Cultural Revolution (1974–75).1 He received an undergraduate degree in philosophy from Peking University in Beijing (1977–80) and was part of the last class comprised of the so-called “worker-peasant-soldier students.” Zhao also attended the graduate program in currency and banking at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (1996–98) and the graduate program in politics at the Central Party School (2002–05), both via part-time studies.

In the Department of Commerce of the Qinghai provincial government, Zhao served as a communications officer (1975–77) and as a clerk in the political division (1980–82). Between 1980 and 1983, he served in various roles within the Qinghai Provincial Commerce School, namely instructor, Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) secretary, and deputy head of the dean’s office. Zhao continued to advance his career in Qinghai, where he served as deputy party secretary of the political division and CCYL secretary of the Commerce Department (1983–84). He then was general manager and party secretary of the Electronic and Chemical Corporation of Qinghai (1984–86) before serving as deputy director and deputy party secretary (1986–91) and then director and party secretary (1986–93) of the Department of Commerce in the Qinghai provincial government. Next, he was promoted to assistant governor (1993–94) and then vice-governor (1994–97) of Qinghai Province. Finally, he served as party secretary of Xining City (1997–99), governor of Qinghai (2000–03), and party secretary of Qinghai (2003–07). Zhao was only 42 years old when he first took the post of Qinghai governor in 2000, becoming the youngest governor in the country. When he was promoted to party secretary, he became the country’s youngest provincial party secretary. After Qinghai, Zhao was transferred to Shaanxi Province, where he served as party secretary (2007–12). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Like Xi Jinping, Zhao Leji has a strong “Shaanxi connection.” His father was a native of Xi’an and served as a department-level official. According to some unverified sources, Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, was close friends with Zhao Leji’s father.2 As a native of Shaanxi, Zhao speaks with a strong regional accent. Some analysts have characterized him as the “spokesperson” of Xi Jinping’s Shaanxi Gang.3 Zhao served as Shaanxi party secretary from 2007 to 2012 before moving to Beijing to head the Central Organization Department. His brother, Zhao Leqin, also served as a leader in Shaanxi for more than two decades, holding posts such as party secretary of Shanyang County, deputy director of the Department of Transportation in the Shaanxi provincial government, and mayor of Hanzhong. Zhao Leqin was transferred from Shaanxi to Guangxi a few months after his brother was appointed provincial party secretary of Shaanxi. In January 2013, he was appointed party secretary of Guilin City, Guangxi. Zhao Leqin is a delegate to the 19th Party Congress.

The Central Organization Department makes appointments for 4,000 senior positions in the party, government, military, state-owned enterprises, and other key institutions.4 As head of that department, Zhao Leji has helped promote many of Xi Jinping’s protégés and like-minded officials to important posts.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

Zhao has been seen as a rising star in the Chinese provincial leadership for more than a decade. Having served as provincial party secretary in both Qinghai and Shaanxi in the Hu Jintao era and, now, having overseen personnel appointments during Xi’s first term, Zhao was expected to obtain a seat on the 19th Politburo Standing Committee. In addition, he was appointed to the key role of secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. It should be noted that Zhao is seven years younger than Li Zhanshu. Therefore, he can serve in the Politburo Standing Committee for this term and the subsequent term, whereas Li Zhanshu’s age limits him to a single term. Based on his previous work experience, Zhao is well positioned on the policy front to carry out several of Xi’s long-standing objectives: the alleviation of poverty and the strict enforcement of regulations on party officials.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- Unverified sources have stated that Zhao Leji’s father was Zhao Shoushan, who served as Shaanxi governor in the 1950s. But Zhao Shoushan, who was born in 1894, seems too old to have been Zhao Leji’s father. Zhao Shoushan’s close relationship with Xi Zhongxun, however, is well documented. Li Jingning, “Xi Zhongxun and Zhao Shoushan” [Xi Zhongxun he Zhao Shoushan], Glory World [Yanhuang shijie], No. 3, 2012; also see http://news.ifeng.com/history/zhongguoxiandaishi/detail201301/23/215133950.shtml. According to another unverified source, Zhao’s father used to be president of the Shaanxi Education Publishing House. See Xiang Jiangyu, Xi Jinping’s Team [习近平的团队] (New York: Mirror Books, 2013), p. 235.

- Ibid., p. 230. See also Yang Qingxi and Xia Fei, Provincial chiefs go to Beijing for the 18th Party Congress [18大诸侯进 京] (New York: Mirror Books, 2010).

- For instance, Zhao Leji has aggressively promoted members of the Shaanxi Gang to important leadership posts. See Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), pp. 316–19.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Han Zheng 韩正

- Born 1954

- Member of the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) (2017–present)

- Party Secretary of Shanghai (2012–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Han Zheng was born in April 1954 in Shanghai. His ancestral home is Cixi City, Zhejiang Province. Han joined the CCP in 1979. He was a “sent-down youth” at a collective farm in Chongming County, Shanghai, during the Cultural Revolution (1972–75).1 Han attended a two-year college program at Fudan University in Shanghai (1983–85), studied for his undergraduate degree (via part-time studies) in politics at East China Normal University in Shanghai (1985–87), and graduated with a master’s in international political economy from East China Normal University (1994–96).

Throughout the early part of his career, Han worked at the grassroots level, including as part of a lifting installation company’s warehouse in Xuhui District, Shanghai, and as a clerk in the supply and marketing division of the same company. He served as deputy secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) (1975–80) and as a clerk of the Shanghai Chemical Equipment Industry Co., Ltd (1980–82). After that, he was secretary of the CCYL committee of the Chemical Industry Bureau of the Shanghai municipal government (1982–86), deputy party secretary of the Shanghai School of Chemical Engineering (1986–87), party secretary and deputy director of Shanghai No. 6 Rubber Shoes Factory (1987–88), and party secretary and deputy director of the Dazhonghua Rubber Plant in Shanghai (1988–90).

Subsequently, Han served as deputy secretary (1990–91) and secretary (1991–92) of the CCYL Shanghai Municipal Committee. He was next appointed deputy party secretary and head of the Luwan District in Shanghai (1992–95) and was eventually promoted to deputy secretary-general (chief of staff) of the Shanghai municipal government, in addition to director of the City Planning Commission and director of the Securities Management Office (1995–97). He became a member of the Standing Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee while continuing to work as deputy secretary-general (1997–98).

He continued to advance his career in Shanghai, serving as vice-mayor (1998–2003), deputy party secretary (2002–12), mayor (2003–12), acting party secretary (2007), and finally party secretary (2012–present). He also served as deputy head of the 2010 Shanghai World Expo Organizing Committee and head of the Executive Committee (2004–11). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Family and Patron-Client Ties

Han has spent his entire career working in Shanghai, where he met five of his patron-mentors, namely Huang Ju, Wu Bangguo, Zhu Rongji, Zeng Qinghong, and Yu Zhengsheng, all of whom later served as members of the Politburo Standing Committee.2 Han has been widely recognized as a member of the Jiang Zemin-Zeng Qinghong “Shanghai Gang.” Although Han served as a top CCYL official in Shanghai, his promotions have been more closely aligned with Jiang’s Shanghai Gang than with the Hu Jintao-Li Keqiang CCYL faction.3 Han also developed a good relationship with Xi Jinping when Han served as Xi’s deputy in Shanghai in 2007, before Xi moved to Beijing to serve as a member of the Politburo Standing Committee. Han apparently earned Xi’s support, obtaining a Politburo seat after Xi became general secretary of the CCP in 2012.

Not much information is available about Han Zheng’s family. According to an unverified source, Han Zheng’s wife, Wang Ming, previously served as vice-chair of the Shanghai Charity Foundation. The couple has one daughter.

Political Prospects and Policy Preferences

As a top administrator of China’s pacesetting city for the past two decades, Han Zheng has emerged as a top economic decision-maker in the national leadership following the 19th Party Congress. In addition to winning a seat on the Politburo Standing Committee, he is likely to become executive vice-premier of the State Council in March 2018, the position filled by his mentor and predecessor in Shanghai—Huang Ju. Han’s reputation as a competent, seasoned financial and economic technocrat, as well as his market-friendly policy orientation in Shanghai, will likely be well received in business communities both in China and abroad.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

- In 1988, for example, Zhu Rongji, then mayor of Shanghai, visited the city’s Dazhonghua Rubber Plant, where Han Zheng was employed. During the visit, Zhu lauded Han’s work. See Xu Yanyan, “Han Zheng recalls Zhu Rongji’s visit to factory” [韩正回忆朱镕基下工厂], China Business Network, August 14, 2013, http://www.yicai.com/news/2939288.html.

- Cheng Li, Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press, 2016), p. 281.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Ding Xuexiang 丁薛祥

- Born 1962

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Executive Deputy Director of the General Office of the CCP Central Committee (2016–present)

- Director of the Office of the General Secretary (2013–present)

- Alternate member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Ding Xuexiang was born in September 1962 in Nantong City, Jiangsu Province. He joined the CCP in 1984. Ding received a bachelor’s degree in engineering from the Department of Machinery Manufacturing at the Northeast Institute of Heavy Machinery in Qiqihar City, Heilongjiang Province (1978–82).1 Ding also received a master’s degree in science (via part-time studies, 1994–96), but the school where he undertook his graduate studies is unknown.

Ding advanced his early political career in Shanghai. After graduating from college in 1982, he began working at the Shanghai Research Institute of Materials, where he served as a research fellow (1982–84); deputy director of the General Office and, concurrently, secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League Committee (1984–88); director of the General Office and director of the Propaganda Department (1988–92); and director of the No. 9 Department (1992–94). He was then promoted to deputy director of the institute (1994–96). Finally, he was promoted to director and, concurrently, deputy party secretary (1996–99).

After that, Ding served as deputy director of the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission (1999–2001); deputy party secretary and head of the Zhabei District of Shanghai (2001–04); and deputy director of the Organization Department of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee and, concurrently, director of the Personnel Bureau of the Shanghai municipal government (2004–06). In 2006, Ding was appointed deputy secretary general (deputy chief of staff) and, concurrently, director of the General Office of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee. In 2007, he was promoted to secretary general (chief of staff), primarily assisting the party secretaries of Shanghai: first Chen Liangyu (2006–07), then Han Zheng and Xi Jinping (2006–07), and finally Yu Zhengsheng (2007–12). Ding served as a member of the Standing Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee (2007–13) and as secretary of the Political and Legal Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee (2013). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 18th Party Congress in 2012.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- It is now named Yanshan University.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Wang Chen 王晨

- Born 1950

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Vice Chairman of the National People’s Congress (NPC) (2013–present)

- Secretary-General of the NPC (2013–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Wang Chen was born in December 1950 in Beijing. He joined the CCP in 1969. He received an undergraduate education in Chinese literature, but it is unclear where and when he studied. He received a master’s degree in journalism from the Department of Journalism at the Chinese Academy of Social Science (CASS) in Beijing (1979–82).

He a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Yijun County, Yan’an Prefecture, Shaanxi Province (1969–70).1 He then worked as a clerk in the Propaganda Department and the County Office of Yijun County, Shaanxi Province (1970–73) and as a clerk in the General Office of the Yan’an Prefecture Party Committee (1973–74). He worked as a reporter on domestic affairs for Guangming Daily (1974–79). After graduating from the CASS, he continued to work for Guangming Daily, where he served as reporter on political and economic affairs and deputy director (1982–84) and director (1984) of the Mass Media Department. He served as director of the Office of the Editor-in-Chief (1984–86), deputy editor-in-chief (1986–95), and editor-in-chief (1995–2000) of Guangming Daily.

He served as deputy director of the Central Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee (2000–01), editor-in-chief of People’s Daily (2001–2003) and as president of People’s Daily (2002–08) at the same time he attended a short program at the Central Party School in Beijing (2006). He served as deputy director of the Central Propaganda Department, director of the Central Foreign Propaganda Office of the CCP Central Committee, director of the State Council Information Office, and director of the National Internet Information Office (2008–13). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

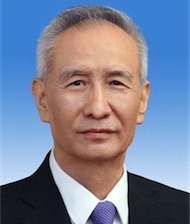

Liu He 刘鹤

- Born 1952

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Director of the General Office of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work of the CCP Central Committee (2013–present)

- Vice-Minister and Deputy Party Secretary of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) (2013–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Liu He was born on January 25, 1952, in Beijing. His ancestral home is Changli County, Hebei Province. It is unclear when Liu joined the CCP. He received a bachelor’s degree in economics (1978–82) and a master’s degree in management (1983–86), both from the Department of Industrial Economics at Renmin University of China in Beijing. He received an MBA from the School of Business Administration at Seton Hall University (1992–93) and an MPA from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1994–95), where he was a Mason Research Fellow. Liu was a founder and convener of the Chinese Economists 50 Forum.1 He serves as a professor of economics at Renmin University of China, Peking University, Tsinghua University, and the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Liu began his career as a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune in Jilin Province (1969–70).2 He also served as a soldier in the 38th Group Army of the PLA (1970–73). After demobilization from the military, he worked as a manual laborer and then as an official in the Beijing Radio Factory (1974–78). He later taught at Renmin University of China as an instructor (1986–87). After that, he worked as a researcher at the Development Research Center of the State Council (1987–88). He then served as deputy director of the Research Office and then deputy director of the Industrial Policy and Long-term Planning Department in the State Planning Commission (1988–98). He was subsequently promoted to director of the State Information Center (1998–2001). He then served as deputy director of the State Council Information Office, where he was in charge of e-commerce and international cooperation (2001–03).

Liu served as deputy director of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Work, where he was responsible for overseeing macro-economic policy planning and drafting speeches for CCP General Secretary Hu Jintao to deliver at the annual CCP national conference on economic affairs (2003–11). He then served as party secretary and deputy director of the Development Research Center of the State Council (2011–13). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 18th Party Congress in 2012.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- The Forum consists of the country’s most influential economists and financial technocrats, including the current governor of the People’s Bank, Zhou Xiaochuan; executive vice-governor Yi Gang; and former minister of finance, Lou Jiwei. The mission of the Forum is to provide policy recommendations to the government on major economic issues. For more information, see http://www.50forum.org.cn/home/article/jianjie.html.

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Xu Qiliang 许其亮

- Born 1950

- Vice-Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) (2012–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2002–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Xu Qiliang was born in March 1950 in Linqu County, Shandong Province. He joined the PLA in 1966 and the CCP in 1967. He studied at the PLA Air Force No. 1 Preparatory School in Shenyang City, Liaoning Province (1966). He received a military education in aviation from the PLA Air Force’s No. 8 Aviation School in Shenyang, Liaoning (1967–68), and the PLA Air Force’s No. 5 Aviation School in Wuwei City, Gansu Province (1968–69). He also attended the senior officer class at the PLA Air Force Academy in Xinyang City, Henan Province (1982). At the National Defense University in Beijing, he studied in the Basic Operations Department (1986–88), attended the Battle Operations Seminar (1994), participated in a program in defense research (1998), and participated in a class for military leaders at the full army commander level (2001).

He advanced his early military career first as a pilot, then as deputy head and head of an aviation brigade, and finally as deputy commander of a division (1969–83). He served as commander of the PLA Air Force Division (1983–84), deputy commander of the PLA Air Force (1984–85), and chief of staff of the Air Force Command in Shanghai (1985–86). He served as acting deputy commander of the PLA Air Force (1988–89), chief of staff and commander of the PLA Air Force (1989–93), deputy chief of staff of the PLA Air Force (1993–94), and chief of staff of the PLA Air Force (1994–99). He then served concurrently as deputy commander of the Shenyang Military Region and commander of the PLA Air Force in the Shenyang Military Region (1999–2004). After that, he was promoted to deputy chief of the PLA General Staff Headquarters (2004–07), during which time he also served as commander in chief of the Peace Mission of Joint Anti-Terrorism Operation Exercises (2007). He also served as commander of the PLA Air Force and as a member of the CMC (2007–12). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 14th Party Congress in 1992.

Xu attained the rank of major general in 1991 and the rank of lieutenant general in 1996. He has held the rank of general in the PLA Air Force since 2007.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Sun Chunlan 孙春兰

- Born 1950

- Director of the Central United Front Work Department of the CCP Central Committee (2014–present)

- Member of the Politburo (2012–present)

- Full member of the CCP Central Committee (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Sun Chunlan was born on May 24, 1950, in Raoyang County, Hebei Province. She joined the CCP in 1973. She received a technical education from the Anshan Institute of Iron and Steel Technology in Anshan City, Liaoning Province (1965–69)1. She later studied economic management in the Department of Economics at Liaoning University in Shenyang, Liaoning Province (via correspondence studies, 1981–84); participated in a program in economic management at the Liaoning Party School in Shenyang City, Liaoning Province (via correspondence studies, 1989–91); and attended a one-year training program at the Central Party School in Beijing (1992–93). She also completed a master’s program in management at Liaoning University in Shenyang (via part-time studies, 1992–95) and a master’s program in politics at the Central Party School (via part-time studies, 2000–03).

Sun began her career as a worker in a watch factory in Anshan (1969) and, eventually, worked as a party official in the same factory (1971–74). She served as secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League (CCYL) of the Light Industry Bureau of Anshan City (1974–77), and served as a manager and party official of the Anshan Textile Factory (1977–88). She was head of the Women’s Association of Anshan City (1988–91), deputy head of the Workers’ Union of Liaoning Province (1991–93), head of the Women’s Association of Liaoning (1993–94), head of the Workers’ Union of Liaoning (1994–97), and deputy party secretary of Liaoning (1997–2005). She also served as party secretary of Dalian, Liaoning (2001–05), and as first secretary of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) (2005–09). Most recently, she served as party secretary of Fujian (2009–12) and party secretary of Tianjin (2012–14). She was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 15th Party Congress in 1997.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- In 2002, the school was renamed the Anshan Institute of Science and Technology. Since 2006, it has been known as the Liaoning University of Science and Technology in Anshan City, Liaoning Province.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Li Xi 李希

- Born 1956

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Party Secretary of Liaoning Province (2015–present)

- Chairman of the Liaoning Provincial People’s Congress (2015–present)

- Alternate member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li was born on October 16, 1956, in Liangdang County, Gansu Province. Li joined the CCP in 1982. He received an undergraduate education in Chinese language and literature from Northwest Normal University in Lanzhou City, Gansu Province (1978–82), and an MBA from the School of Economics and Management at Tsinghua University in Beijing (2008–11).

He was a “sent-down youth” at Yunping People’s Commune in Liangdang County, Gansu Province (1975–76)1. He served as a clerk at the Culture and Education Bureau and the Party Committee of Liangdang County (1976–78). After graduating from college in 1982, he worked as a mishu (personal assistant) in the Department of Propaganda of the Gansu Provincial Party Committee (1982–85) and as a mishu in the office of Gansu Party Secretary Li Ziqi (1985–86). Li Xi worked as an official (1986–87), deputy division head (1987–90), and division head (1990–95) in the Organization Department of the Gansu Provincial Party Committee. He served as party secretary of Xigu District, Lanzhou City (1995–96). After that, he served as director of the Organization Department (1996–99) and, concurrently, as deputy party secretary (1999–2001) of the Lanzhou Municipal Party Committee. He served as party secretary of the Zhangyi Prefecture Party Committee (2001–04), during which time he attended a four-month, mid-career training program at the Central Party School (2004). He became secretary-general (chief of staff) of the Gansu Provincial Party Committee for a few months in 2004 and then was transferred to Shaanxi, where he served as secretary-general (chief of staff) and was a member of the Standing Committee of the Shaanxi Provincial Party Committee (2004–06). He concurrently served as party secretary of the Yan’an Municipal Party Committee (2006–11). In 2011, he was transferred to Shanghai, where he served as director of the Organization Department and as a member of the Standing Committee of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee (2011–13), and then as deputy party secretary of Shanghai (2013–14). Finally, he was appointed deputy party secretary and governor of Liaoning Province (2014–15) and then promoted to party secretary in 2015. He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 17th Party Congress in 2007.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Li Qiang 李强

- Born 1959

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Party Secretary of Jiangsu (2016–present)

- Chairman of the Jiangsu Provincial People’s Congress (2017–present)

- Alternate member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li Qiang was born in July 1959 in Rui’an City, Caocun County, Zhejiang Province. Li joined the CCP in 1983. He received an undergraduate education in agricultural mechanization at the Zhejiang Institute of Agriculture’s Ningbo campus in Ningbo City, Zhejiang (1978–82). In addition, he attended a graduate program in management engineering at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, Zhejiang (via part-time studies, 1995–97); a year-long, full-time training program for young and middle-age cadres at the Central Party School (CPS) in Beijing (2001–02); and a part-time graduate program in world economics at the CPS (2001–04). He also received an MBA from Hong Kong Polytechnic University in Hong Kong (via part-time studies, 2003–05).

Li began his career as a worker, first at an electromechanical irrigation and drainage station in Mayu District, Rui’an County (1976–77), and then at the No. 3 Tools Factory in Rui’an County (1977–78). He served as a clerk and an official of the CCYL Committee of Xincheng District, Rui’an County (1982–83), and as secretary of the CCYL Committee of Rui’an County (1983–84). He also served as deputy division head and division head of the Rural Relief Division of the Zhejiang Provincial Civil Affairs Department (1984–91), then as director of the Personnel Division of the Zhejiang Provincial Civil Affairs Department (1991–92), and finally as deputy director of the Zhejiang Provincial Civil Affairs Department (1992–96). Following those roles, he served as a member of the Standing Committee of Jinhua City, Zhejiang, and as party secretary of Yongkang City, Zhejiang (1996–98). Next, he served as deputy director of the general office of the Zhejiang provincial government (1998–2000), and then as director and party secretary of the Bureau of Administration for Industry and Commerce in the Zhejiang provincial government (2000–02). After that, he was appointed party secretary of Wenzhou City, Zhejiang (2002–04). He then became secretary-general (chief of staff) of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee (2004–12). Finally, he served as secretary of the Zhejiang Provincial Commission of Politics and Law (2011–12), as deputy party secretary of Zhejiang (2011–16), and as governor of Zhejiang (2013–16). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 18th Party Congress in 2012.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

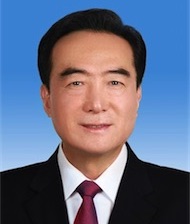

Li Hongzhong 李鸿忠

- Born 1956

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Party Secretary of Tianjin (2016–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Li Hongzhong was born in August 1956 in Shenyang, Liaoning Province. His ancestral home is Changle County, Shandong Province. Li joined the CCP in 1976. He was a “sent-down youth” at an agricultural commune near Shenyang City, Liaoning (1975–78).1 He received his bachelor’s degree in history from Jilin University in Changchun City, Jilin Province (1978–82); attended a mid-career training program at the Central Party School in Beijing (1996–97); and attended a month-long program for “Future Leaders” at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University (1999).

Li’s early career consisted primarily of service as a personal assistant (mishu). Li began his career as mishu to his patron-mentor, Li Tieying, in the CCP Municipal Committee of Shenyang City and later in the CCP Committee of Liaoning Province (1982–85). Li Hongzhong continued to work as a mishu for Li Tieying when the latter moved to Beijing to serve as minister in the Ministry of the Electronics Industry (MEI) (1985–88).

In 1988, Li Hongzhong was transferred to Huizhou City, Guangdong Province, where he served as vice-mayor (1988–95), deputy party secretary and mayor (1995–2000), and party secretary (2000–01). Li was promoted to vice-governor (2001) and then executive vice-governor (2003) of Guangdong Province. Li went on to serve as mayor of Shenzhen (2004–05) and party secretary of Shenzhen (2005–07). In 2007, Li was appointed acting governor and deputy party secretary of Hubei Province. He served as governor and deputy party secretary of Hubei Province (2008–10) before he was promoted to party secretary of Hubei (2010–16). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Yang Jiechi 杨洁篪

- Born 1950

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- State Councilor of the State Council (2013–present)

- Director of the Office of the Central Leading Group for Foreign Affairs (2013–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Yang Jiechi was born in May 1950 in Shanghai. He joined the CCP in 1971. He began his career as a factory worker at Pujiang Ammeter Factory in Shanghai (1968–72). He was selected to participate in a training program for Overseas Studies at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) (1972–73). He received an undergraduate education in international relations from the University of Bath in Bath, United Kingdom, and graduated with a master’s degree in economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in London, United Kingdom (1973–75). He pursued graduate studies in history at Nanjing University in Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province (via part-time studies, 2001–06), and received a doctoral degree in 2006. He also attended short-term executive program for ministerial and provincial level leaders at the Central Party School (CPS) in Beijing in 1996.

He worked as a staff member and 2nd Secretary at the MOFA (1975–83). He served as 2nd secretary, 1st secretary and counselor in the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C. (1983–87). He served as counselor and division head of the Translation and Interpretation Department in the MOFA (1987–90) at the same time he was serving as an interpreter for Deng Xiaoping. He served as a counselor, division head and deputy director of the North American and Oceania Affairs Department of MOFA (1990–93). He was appointed deputy chief-of-mission at the Chinese Embassy in Washington D.C. (1993–95). He served as assistant minister (1995–98) and vice minister (1998–2000) of the MOFA. He served as ambassador to the United States (2000–04). He served concurrently as vice minister and deputy party secretary of the MOFA (2005–07), and concurrently as minister and deputy party secretary of the MOFA (2007–13). He was first elected to the Central Committee as an alternate member at the 16th Party Congress in 2002.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Yang Xiaodu 杨晓渡

- Born 1953

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Deputy Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) (2014–present)

- Minister of Supervision (2016–present)

- Director of the National Bureau of Corruption Prevention (2017–present)

- Member of the CCDI (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Yang Xiaodu was born in October 1953 in Shanghai. He joined the CCP in 1973. As an undergraduate, he studied pharmacy in the Department of Pharmacy at the Shanghai Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Shanghai (1973–76).1 He also received a master’s degree in law from the Central Party School (CPS) in Beijing (via part-time studies, 1998–2001) and attended an executive training program for ministerial and provincial level leaders at the CPS (2013–14).

Yang was a “sent-down youth” in the Songji Commune, Taihe County, Anhui Province (1970–73).2 After graduating from college, he moved to Tibet Autonomous Region (AR), where he served as division head and deputy general manager of a medical company in Nagqu Prefecture (1976–84). He then served as party secretary of the Hospital of Nagqu Prefecture, Tibet AR (1984–86). After that, he served as deputy commissioner of Nagqu Prefecture, Tibet AR (1986–92), and deputy party secretary and deputy commissioner of Changdu Prefecture, Tibet AR (1992–95). He then served as director of the Department of Finance of the Tibet AR government (1995–98) and vice-governor of Tibet AR (1998–2001).

In 2001, after working in Tibet for about 25 years, he returned to his native city of Shanghai. He served as vice-mayor of Shanghai (2001–06). He then served as director of the United Front Work Department in the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee (2006–13) and secretary of the Discipline Inspection Commission of the Shanghai Municipal Party Committee (2012–13). In 2013, he was named head of the 3rd Inspection Team of the CCDI, in charge of anti-corruption work at the Ministry of Land and Resources. He was first elected as a member of the CCDI at the 18th Party Congress in 2012.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at BrookingsNotes

- China did not offer academic degrees until 1981.

- “Sent-down youth” (插队知青) refers to young, educated urbanites who left their home cities to serve as manual laborers in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Zhang Youxia 张又侠

- Born 1950

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Member of the Central Military Commission (CMC) (2012–present)

- Commander of China’s Manned Space Program (2012–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2007–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Zhang Youxia was born in July 1950 in Beijing. His ancestral home is Weinan City, Shaanxi Province. He joined the PLA in 1968, but it is unclear when he joined the CCP. His educational background is also unclear, except for the fact that he attended the Jingshan School in Beijing as a high school student (1965–68).

Zhang advanced his military career step-by-step as a soldier, a squad leader, a platoon leader, a company commander, a battalion commander, and a deputy commander in a regiment (1968–84). A veteran of both the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War and the Battle of Laoshan between China and Vietnam in 1984, he is one of few serving generals in China with wartime experience. He served as regiment commander, deputy division commander, and deputy commander of the 13th Group Army (1984–2000). He was then promoted to commander of the 13th Group Army (2000–05). After that, he served as deputy commander of the Beijing Military Region (2005–07) and commander of the Shenyang Military Region (2007–12). He served as director of the PLA General Equipment Department (2012–16) as well as director of the newly established PLA Central Military Commission Equipment Development Department (2016–17). He was first elected to the Central Committee as a full member at the 17th Party Congress in 2007.

Zhang assumed the rank of major general in 1997 and the rank of lieutenant general in 2007. He has held the rank of general since 2011.

Compiled by Cheng Li and the staff of the John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings Download Profile as PDF

Download Profile as PDF

Chen Xi 陈希

- Born 1953

- Member of the Politburo (2017–present)

- Executive Deputy Director of the Central Organization Department (2013–present)

- Full member of the Central Committee of the CCP (2012–present)

Personal and Professional Background

Chen Xi was born in September 1953 in Putian City, Fujian Province. He joined the CCP in 1978. Chen received an undergraduate education in chemical engineering from Tsinghua University in Beijing (1975–79). After graduating, Chen worked as an instructor for five months in the Department of Chemical Engineering at Fuzhou University, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province (1979). Chen then obtained a master’s degree in chemical engineering from Tsinghua University (1979–82). He went on to conduct chemical engineering research as a visiting scholar at Stanford University (1990–92).