This post has been updated on January 24 to reflect new information.

While the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, has been criticized by its opposition as “socialized medicine,” it relies heavily on private health insurance. On the other end of the political spectrum is the idea that a government-run single payer system, similar to Canada’s, is the best way to deliver health care. (This is sometimes shorthanded in the U.S. as “Medicare for All.”) However, this system has been believed politically impossible here—until now. In May 2011, Governor Pete Shumlin of Vermont signed into law “An Act Relating To A Universal And Unified Health System,” House Bill 202 (HB 202), establishing a single payer health care system beginning in 2017. In passing this legislation, Vermont has become a closely watched laboratory for health reform.

What are the pros and cons of a “single payer” system?

In general, single payer health care means that all medical bills are paid out of a single government-run pool of money. Under this system, all providers are paid at the same rate, and citizens receive the same health benefits, regardless of their ability to pay.

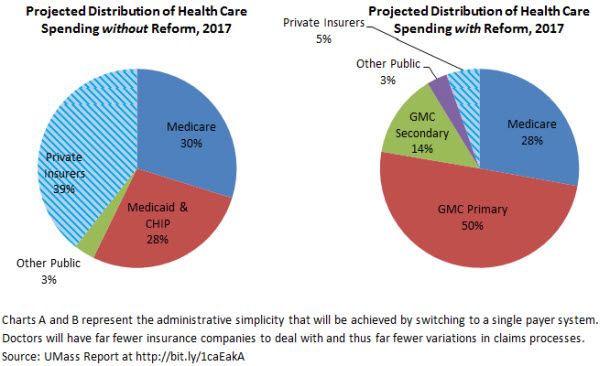

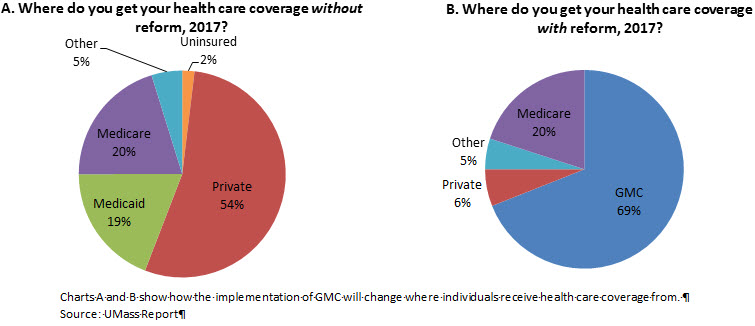

There are a number of proposed benefits to a single payer system. Currently, providers must follow different procedures with each of many insurance companies to get paid, creating an enormous amount of administrative work. Under a single payer system, providers might reap significant savings from reduced administrative expenses, and be able to focus more on delivering care. As with Medicare, a single payer system may also give the state stronger leverage to negotiate lower rates for drugs, medical devices, payments to providers and other expenses, resulting in lower overall costs. Additionally, a single payer system provides universal access to health insurance, which eliminates the problem of the uninsured.

However, Vermont’s innovative proposal still leaves room for further improvement. Specifically, a single payer system alone does not address “fee-for-service” reimbursement for providers, which may encourage overuse and does not recognize quality and value. Other concerns also exist. Generally, private insurance rates have been substantially higher than Medicare rates, and providers worry that universal rate setting may lead to overall lower revenues. Others have worried that Vermont does not have enough doctors, and an influx of newly insured citizens may result in longer wait times and inability to access health care when necessary.

What does Vermont’s law actually do?

HB 202 established Green Mountain Care (GMC) and sets Vermont on track to have a single payer health care system beginning in 2017.

Here’s how it will work: All Vermont residents will automatically be eligible for GMC. Private insurance companies will no longer sell insurance in the state, but federal employees as well as employees of self-insured companies, will continue to receive their employer sponsored plans. In these cases, their health insurance will be supplemented by GMC. When a patient with GMC goes to the doctor, hospital or other caregiver, all of their expenses will be billed to GMC. Someone with GMC as their secondary coverage will have this option available to them if their primary insurance is not as comprehensive as GMC.

On the back end, GMC will combine the money Vermont currently receives from Medicaid, other federal funding available through the Affordable Care Act, and a yet-to-be-determined new tax on individuals and employers. For now, Medicare funding will remain separate. However, Vermont may choose to fold this funding into GMC as well, in the future.

The Green Mountain Care Board (GMCB) will control GMC. They will oversee the development and implementation of new payment models, provide a recommendation to the legislature on the benefit package and budget for GMC, and set rates for provider reimbursement. Parts of GMC will also be contracted out to private companies including claims administration and provider relations.

For now, Vermont is still required to set up a health insurance exchange available to all residents, in accordance with the Affordable Care Act. But when GMC rolls out in 2017, the exchange will either be eliminated or may still be available in some form if GMC ends up offering multiple benefit plan options.

What obstacles remain?

To begin with, HB 202 requires the GMCB to certify that Vermont’s plan meets a number of conditions before it can be implemented: GMC will not negatively impact the economy, GMC will reduce the rate of growth of Vermont’s health care costs, the financing plan for GMC will be sustainable, administrative costs will be reduced, all Vermonters will have health insurance that covers at least 80% of their health care costs, and providers will be reimbursed at a reasonable rate. Additionally, Vermont will need to apply for waivers from the federal government, as well as the Medicare and Medicaid programs in order to combine all of the funding it receives from these programs into GMC. These requirements pose a serious challenge to the implementation of GMC. While the state has begun working towards these goals, several uncertainties remain.

First, the state needs to figure out how much the plan will cost. A report from the University of Massachusetts Medical School estimated that the total cost of the healthcare system in 2017 will be $5.9 billion. This number is based on the assumption that GMC would pay providers at 105% of what Medicare currently pays them, which is more than they receive from Medicaid but less than what they currently receive from private payers. Using this estimate, the state would need to raise $1.6 billion to supplement the funding it will receive from the federal government, Medicare and Medicaid. An opposing group, including providers, payers, and the business community commissioned its own report which assumed the rates would be between 115% and 125% of Medicare, raising the cost estimate to between $1.9 and $2.2 billion. The differing estimates in these reports mostly demonstrate the increasing concern from various healthcare stakeholders regarding the Shumlin administration’s plan. However, they also make the point that much is still unknown about how much GMC will cost in 2017.

Second, the state hasn’t decided how to raise this money. The report they released stated that there were a number of possible revenue sources that require further study before a final decision is made. However, Governor Shumlin has indicated that that a payroll tax (similar to the one funding Medicare now) would likely play a large part in the final financing plan. Based on an estimate from the UMass report that a 1% payroll tax could raise $119 million, a financing plan would have to include a fairly large payroll tax or a combination of taxes to cover the $1.6 billion that is estimated to be necessary. (Any tax would be in place of the current premiums and other health insurance costs that individuals and employers pay.) Governor Shumlin has said that he will announce his financing plan in a year, but some believe this is too long to wait. Senator Peter Galbraith, a Democrat, introduced a bill proposing an 11% payroll tax on employers and a 2% payroll tax on individuals, combined with a tax on other earnings such as capital gains, to fund GMC.

Third, planning and execution must proceed in an orderly manner. As the recent Obamacare exchange roll-out demonstrated, this can be a difficult process. Still, such planning has begun. In addition to the looming issues of how much it will cost and where the money will come from, the legislature is beginning to look at when to begin collecting funds, how much providers will be paid, malpractice reform, a benefits package, and many other pertinent issues.

Vermont has committed to an innovative path, even though much is still up in the air as to what Green Mountain Care will actually look like in 2017. One thing is clear, the rest of the country will be watching Vermont’s success or failure closely.

Commentary

Can Canadian-Style Healthcare Work in America? Vermont Thinks So.

January 22, 2014