As British Prime Minister Boris Johnson informed the nation on Monday evening of dramatic new restrictions to stem the spread of coronavirus, Brexit was the last thing on most Britons’ minds. For most citizens and businesses, little has changed in their daily lives since the U.K. left the European Union (EU) on January 31. Although the British government no longer participates in EU decisionmaking institutions, the country remains bound by its rules and enjoys the benefits of membership during a transition period lasting until December 31.

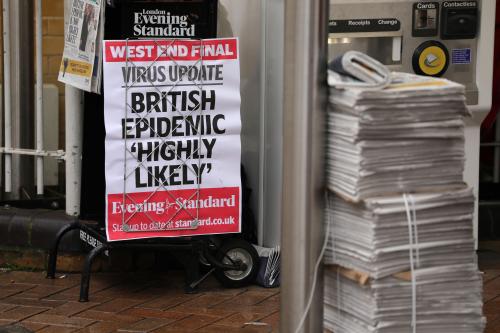

Yet given the COVID-19 pandemic, it is increasingly likely the government will need to extend this timeline or risk additional economic shocks. The crisis is also underscoring the post-Brexit regulatory and coordination challenges ahead.

During the 11-month transition, the U.K. and EU planned to determine their future relationship. They need to hammer out the terms of a free-trade agreement, aspiring to a zero-quota, zero-tariff deal similar to the EU’s recent agreement with Canada. They must also address air transport, aviation safety, civil nuclear energy, international security cooperation, and fisheries. Both sides have published draft documents.

During the first round of face-to-face negotiations on March 2-5, the two sides were cordial but faced “very serious divergences,” in the words of EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier. The second round of talks, scheduled for March 18, was postponed in light of COVID-19. Barnier announced on March 19 that he had coronavirus, while British negotiator David Frost entered self-quarantine the following day after showing symptoms. Beyond the logistical challenges of conducting sensitive discussions via video conference, neither side has the bandwidth to proceed as planned.

The deadline could be changed. The Withdrawal Agreement — the divorce decree outlining the terms of Brexit — anticipated the potential need for more time. Many already feared the timeframe was overly ambitious, allowing only six months in practical terms for talks: The sides first met in March and need a deal by late November to enable parliamentary ratification. (Had the U.K. left on March 29, 2019 as originally envisioned, the transition period would have been 21 months. The December 31, 2020 end date coincides with the conclusion of the EU’s seven-year financial framework, thereby clarifying Britain’s budgetary obligations.) Given the current inability to meet in person due to COVID-19, it now seems virtually impossible. The agreement allows either side to request a one- or two-year extension to the transition period. Then the Joint Committee, which is comprised of U.K. and EU officials, will formally make the decision. However, this must be done by June 30.

Johnson has always opposed an extension. He even tied his own hands: The legislation that implemented Brexit in British domestic law included a provision barring the government from requesting one. His main concern is financial, as the Withdrawal Agreement says an extension would require Britain to make a budgetary contribution given its continued enjoyment of the EU’s single market. In addition, a longer transition would keep Britain subject to EU laws, immigration rules, and judicial system.

Johnson previously threatened to walk away from talks with no trade deal, if British demands were not met. In this case, the U.K. would trade with the EU as a third country, such as Australia, according to World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

Each path includes economic risks. If there is a deal, companies that may emerge from the effects of coronavirus by the fourth quarter will face near-term disruptions. The government’s own long-term analyses in November 2018 found a free trade agreement would reduce GDP by 4.9%, compared to remaining an EU member. British businesses are working to implement practical changes that will take effect at the end of the year, including a new immigration system, regulation, and border checks (especially for Northern Ireland). The government has already warned of Brexit-related disruption, including to supply chains. If there is no trade deal, the government would knowingly be creating a second economic shock. If the government requests an extension, the prospect of additional payments to Brussels — especially if there is a coronavirus-induced recession — will be politically unpalatable, but still the least bad option.

COVID-19 is also highlighting challenges the U.K. will face in coordinating, regulating, and responding to crises after it has fully left the EU. Although the U.K. currently benefits from joint EU measures in response to the crisis, its health minister is not allowed to participate in EU meetings. The British government doesn’t seem to mind, as its delayed introduction of social distancing and other preventative measures made it an outlier in Europe. Johnson has also reiterated that Brexit precludes British participation in EU regulatory systems. He said the U.K. will leave the European Medicines Agency, which is responsible for the scientific evaluation, supervision, and monitoring of medicines. (The agency was based in London, but it moved to Amsterdam in March 2019 during Brexit discussions.) The U.K. has already withdrawn from the EU’s emergency bulk-buying mechanism for vaccines and medicines. Johnson recently announced plans to leave Europe’s aviation safety agency too.

Officially, the British government remains opposed to extending the transition period. If Johnson is able to “turn the tide” against coronavirus within 12 weeks as he initially envisioned, he may feel there is sufficient time to reach an agreement. However, he has recently softened his messaging. At a press conference last week, he said: “There is legislation in place that I have no intention of changing.” Journalists have cited Downing Street sources who believe a delay is likely and confirm such plans exist.

The British public remains polarized. A new YouGov survey found that 55% of people support an extension, with one-quarter opposed and 21% uncertain. Unsurprisingly, Brexiteers are resistant to a longer timeframe. For example, former Brexit minister David Davis was hopeful about a deal earlier this month. He added: “The unfortunate COVID-19 events will mean that cross-border traffic will be depressed and customs will be more than able to handle the traffic.”

Johnson will presumably wait as long as possible to decide, especially as the escalating effects of COVID-19 dominate the headlines. Given his 80-seat majority in Parliament, he has political space to request an extension. With members heading home for an elongated four-week Easter recess after they pass emergency legislation addressing coronavirus, this question will likely wait. Yet for businesses and consumers, clarity is needed sooner rather than later. Under the circumstances, the only responsible option is extending the transition period. The British government should also use this cross-border challenge as an opportunity to think carefully about the nature of its future relationship with its closest neighbors.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Brexit is not immune to coronavirus

March 26, 2020