Yesterday, parents in DC were told whether or not their children won the lottery. That is, whether or not they could attend a school of their choice. Competition over high quality schools was fierce. Just 71 percent of parents got one of their 12 choices and 60 percent got one of their top three choices. Clearly, parents do not want to send their kids to failing schools.

Education reformers agree, and emphasize the power of good schools to educate and empower young people from poor households. Their policy goals include paying teachers based on performance and allowing poor parents alternatives to their failing neighborhood-assigned public schools, including charter schools or publicly-funded vouchers for private schools. Education conservatives, by contrast, oppose those policies and emphasize the debilitating effects that poverty has on education.

So who’s right?

On the one hand, there is impressive evidence that poor children face distinct obstacles to learning. Their parents, on average, spend less time caring for them, talking to them, actively teaching them, and reading to them relative to children of highly educated parents.

Despite all that, reformers have been vindicated by academic scholarship showing high quality schools have hugely important effects on learning. Parents understand this, which is why applications to attend higher-scoring schools are over-subscribed. We also know this from a large and growing body of evidence from school district experiments with using lotteries to randomly assign students to different schools.

I’ve reviewed 15 studies that analyze how some aspect of school quality affects learning or future labor market outcomes, all published since 2002. Only one showed no significant effect—in this case, between schools chosen by parents and neighborhood assigned schools. For studies in which measures of quality are more precise, such as previous teacher performance, the effect is always large and significant. Moreover, the benefits are typically larger for the most disadvantaged students.

The Class Gap in The Classroom

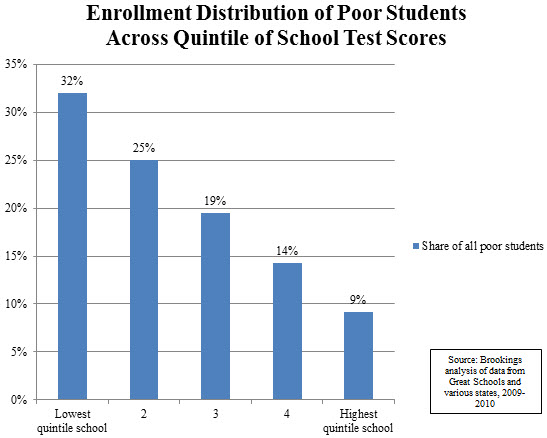

If all children attended equally good schools, we’d still expect some to do better based on the quality of their home schooling. Unfortunately, it is typically the case that children with the least educative home schooling environments are assigned to the least educative public schools. Private disadvantage is thus magnified by public policies that lock poor children into failing classrooms.

How Do We Narrow the Schooling Gap?

So, how do we get more poor children in front of great teachers?

To start, we need to enhance the pool of potential teachers by paying, hiring, training, and firing based on performance and motivation, not seniority. Eventually, this should lead to greater teacher autonomy and satisfaction. More districts also need to follow DC’s lead and open up good schools—public or private—to students living outside of their assignment zone. Schools receiving no or minimal applications should be shut down or reborn under new management. Meanwhile, greater residential and school integration of the poor could be achieved if prosperous neighborhoods adopted more market friendly zoning laws.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Both Quality Parenting and Schooling Matter for Social Mobility

April 1, 2014